Despite the success of Wee Willie Winkie and Heidi, 20th Century Fox decided to table, for the time being at least, any literary pretensions in Shirley’s pictures. In Child Star Shirley says otherwise: “Ahead would be Fanchon the Cricket followed by Pollyanna…” — but nothing ever came of those, and she never mentions either title again, not even to explain why they didn’t happen. Both, not coincidentally, had been Mary Pickford vehicles in 1915 and 1920, respectively.

Fanchon, despite what Shirley says, was almost certainly never on the agenda. The 1849 George Sand novel on which it was based (La Petite Fadette) had no particular following in the U.S., and Pickford’s picture of it was long forgotten — presumed lost, in fact (a partial print didn’t surface until 1999). Besides, the character of a semi-feral peasant girl who wins the love of a respectable village boy in rural France was hardly a good fit for Shirley. Perhaps Mother Gertrude mentioned the title for (or to) Shirley, but Darryl Zanuck surely didn’t.

Pollyanna is another case entirely; why that one never happened is a mystery. The idea was a natural, more natural in fact than Heidi. For that matter, Eleanor H. Porter’s 1913 novel was virtually an American carbon copy of Heidi — without goats and mountains, with an aunt instead of a grandfather, and with Heidi and Klara, the crippled friend who learns to walk again, combined into the one character of Pollyanna Whittier. The story could easily have accommodated as many songs for Shirley as Zanuck and his minions cared to throw at it, and could even have been updated to the 1930s without doing serious damage to the original. Fox’s failure to follow this lead has to count as a major missed opportunity, maybe even (depending on the results, of course) a crime against posterity. Could the problem have been that the Porter novel was still under copyright? I suppose we’ll never know.

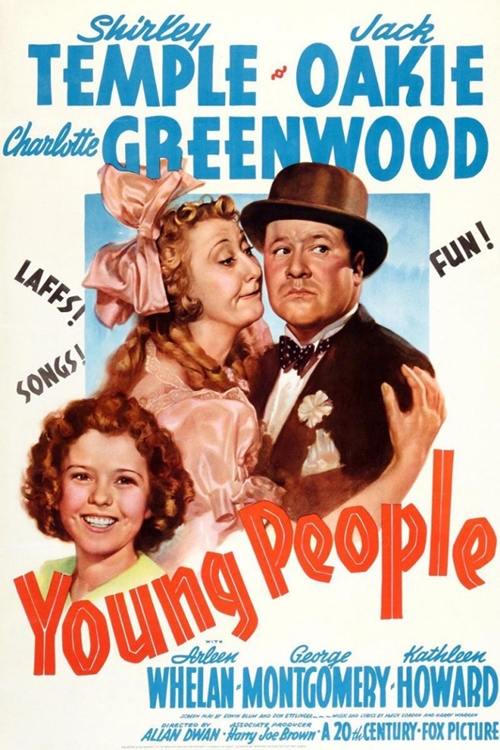

Shirley wrote about Zanuck “grappling with that chronic demon” of “selecting my next screenplay.” The grappling produced results — Shirley made three pictures in 1938 — but the results were, alas, generally undistinguished. Shirley described one of those pictures as “unfailingly bland”, but she could have been talking about any of the three, and we can deal with each of them in a very few paragraphs.

Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm

(released March 25, 1938)

Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm was another of Shirley’s “no trace” pictures, like Poor Little Rich Girl and (allegedly) The Littlest Rebel. What there was no trace of this time was the 1903 novel by Kate Douglas Wiggin. The story had been filmed faithfully in 1917 with Mary Pickford and again in 1932 with Marian Nixon (produced by Fox Film Corp., so the post-merger studio still had the property lying around). For this incarnation, the studio adopted the same curious practice they had used with Poor Little Rich Girl: take a title widely identified with Mary Pickford, then make a picture with absolutely no connection to what Pickford and Co. did with it.

Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm was another of Shirley’s “no trace” pictures, like Poor Little Rich Girl and (allegedly) The Littlest Rebel. What there was no trace of this time was the 1903 novel by Kate Douglas Wiggin. The story had been filmed faithfully in 1917 with Mary Pickford and again in 1932 with Marian Nixon (produced by Fox Film Corp., so the post-merger studio still had the property lying around). For this incarnation, the studio adopted the same curious practice they had used with Poor Little Rich Girl: take a title widely identified with Mary Pickford, then make a picture with absolutely no connection to what Pickford and Co. did with it.

As if to ensure that Rebecca would be as familiar as possible, Zanuck and associate producer Raymond Griffith packed the supporting cast with returnees from Shirley’s earlier pictures: Gloria Stuart and Jack Haley from Poor Little Rich Girl; Helen Westley from Dimples, Stowaway and Heidi; Slim Summerville from Captain January; Bill Robinson from The Little Colonel and The Littlest Rebel; J. Edward Bromberg, the deus ex machina judge from Stowaway, serving the same function as a doctor this time; even Alan Dinehart, the sleazeball detective from way back in Baby Take a Bow, was brought back. Of the names on this poster, only Randolph Scott and Phyllis Brooks were new, and both would work with Shirley again before the year was out. The director, once again, was Heidi‘s reliably unimaginative Allan Dwan.

Even the story was a bit of a recycle; as in Poor Little Rich Girl, Shirley becomes a radio star unbeknownst to her ostensible guardian (duties divided this time between her grumpy aunt Helen Westley and shifty stepfather William Demarest) when, while living with her aunt on the farm of the title, she sneaks out for a remote broadcast from the farmhouse of her neighbor, radio producer Randolph Scott.

During that broadcast, Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm drops all pretense to being anything more than Shirley Temple In Concert. The program’s emcee (Jack Haley) invites Shirley/Rebecca to “sing the songs that made a lot of people happy.” So she sings:

My dear radio audience,

Now I shall do

Some of the songs I’ve had the pleasure of introducing to you…

This, mind you, on what is supposedly her very first broadcast. What follows is a medley of “On the Good Ship Lollipop” from Bright Eyes, “Animal Crackers in My Soup” from Curly Top, “When I’m With You” and “Oh, My Goodness” from Poor Little Rich Girl and “Good Night, My Love” (the lyric changed to “Good Night, My Friends”) from Stowaway. “Ah, but it’s great to reminisce,” Shirley/Rebecca sighs.

Like Captain January, Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm was one of Shirley’s first pictures to hit TV in the 1950s, so it has a special place in the childhood memories of many Baby Boomers. And giving credit where it’s due, Rebecca is a pleasant enough vehicle for Shirley. But it plows familiar ground while the original furrows are still fairly fresh. Those Baby Boomers (including myself) first saw Rebecca on its own, without the feeling of deja vu that comes from knowing about all the other movies it ransacks for actors, songs and plot elements.

“Flin” in Variety wasn’t fooled. He gave Shirley full credit as “a great little artist”, but added:

The rest is synthetic and disappointing. Why they named it “Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm” is one of those mysteries. The only resemblance is a load of hay, a litter of pigs and Bill Robinson’s straw hat.

But Rebecca‘s familiarity doesn’t always breed contempt. The picture ends, and I’ll end my comments on it, with Shirley singing “The Toy Trumpet” by Sidney Mitchell and Lew Pollack, then dancing the song with Bill Robinson. Granted, it’s really just a less-bravura retread of “Military Man” from Poor Little Rich Girl, but hey, it’s still Shirley and Bojangles (yet again, colorized):

Little Miss Broadway

(released July 22, 1938)

Little Miss Broadway

Little Miss Broadway was the one Shirley called “unfailingly bland”, and that about sums it up. Shirley is once again an orphan, this time moving from her orphanage to live with a friend of her late parents (Edward Ellis) who runs a hotel for entertainers. The curmudgeon this time is the rich old landlady next door (Edna May Oliver, her middle name misspelled as “Mae”), who not only plots to get rid of those unsavory show people by selling their hotel out from under them, but (channeling Sara Haden’s truant officer from

Captain January) moves to have Shirley returned to her orphanage. Meanwhile, her playboy nephew (George Murphy) is charmed by Shirley and smitten with Ellis’s daughter (Phyllis Brooks of

Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm) and tries to thwart the old girl. It all ends in the courtroom of judge Claude Gillingwater, with Shirley and her troupers proving that they’ve got a moneymaking show on their hands and can afford to keep the hotel open.

Little Miss Broadway was the first of two straight pictures Shirley made with associate producer David Hempstead. The other pictures Hempstead would make at Fox before decamping to RKO in 1940 were Happy Landing, Hold That Co-ed, Straight Place and Show and It Could Happen to You — not B pictures exactly, but definitely A-minus, and the same must be said for both of Shirley’s pictures for him. Even Mother Gertrude had noticed, with some alarm, the budget cutbacks in Shirley’s pictures, and there’s a chintzy, slapdash quality to Little Miss Broadway. It shows in odd ways, too — for example, the fact that Edna May Oliver, at the time one of the best-known and most popular character actresses in movies, couldn’t even get her name spelled correctly in the credits. (Also, the fact that as curmudgeon du jour, she doesn’t actually get won over by Shirley; like grumpy aunt Helen Westley in Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, she just stops being a curmudgeon and turns nice when the Harry Tugend-Jack Yellen screenplay decides it’s time.) And by the way, the thought of Shirley and Jimmy Durante in a movie together may sound promising, but it’s just a tease; he spends more time flirting with soubrette Patricia Wilder at the hotel’s switchboard than he does on screen with Shirley.

In Child Star Shirley spends less time talking about the picture itself than about First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt’s visit to the set during production. ‘Nuff said.

But at least Shirley had a couple of nice dance turns with George Murphy. One was the climactic title number (by Walter Bullock and Harold Spina), in which George and Shirley’s song-and-dance magically turns Judge Gillingwater’s courtroom into a glittering Busby Berkeley-style replica of Times Square. But I’m posting here their earlier number, “We Should Be Together” (also by Bullock and Spina); the colorized YouTube clip is better quality, and besides, the number itself is more fun:

In the New York Times, Frank S. Nugent was rather sympathetic: “The devastating Mistress Temple is slightly less devastating than usual in ‘Little Miss Broadway,’…Although she performs with her customary gayety [sic] and dimpled charm, there is no mistaking the effort every dimple cost her.” Variety’s “Flin” added: “Shirley is better than her new vehicle, which in turn is better than her last one, ‘Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm.'” Whether Little Miss Broadway was really better than Shirley’s last vehicle is open to debate. But it was certainly better than her next one.

Just Around the Corner

(released December 2, 1938)

If Little Miss Broadway was an A-minus picture, Just Around the Corner was no more than a B-plus. If that. Shirley plays Penny Hale, who is taken out of private school when her widowed architect father (Charles Farrell) loses his job, and consequently the penthouse he and Penny have been living in, as well as the money to pay for her school. He’s now forced to work as the electrician in the apartment building where they formerly occupied the penthouse, and he and Penny must now make do with a tiny apartment in the basement.

If Little Miss Broadway was an A-minus picture, Just Around the Corner was no more than a B-plus. If that. Shirley plays Penny Hale, who is taken out of private school when her widowed architect father (Charles Farrell) loses his job, and consequently the penthouse he and Penny have been living in, as well as the money to pay for her school. He’s now forced to work as the electrician in the apartment building where they formerly occupied the penthouse, and he and Penny must now make do with a tiny apartment in the basement.

The penthouse now belongs to tycoon Samuel G. Henshaw (Claude Gillingwater again), the uncle of Penny’s new playmate Milton (Bennie Bartlett) and her father’s sweetheart Lola (Amanda Duff). This coincidence leads Penny to confuse the real man with the symbolic “Uncle Sam” — after all, he has the same white goatee — and to set about pulling him, her father and the country out of the economic doldrums by staging a benefit show at five cents admission.

Just Around the Corner, like Little Miss Broadway before it, was directed by Irving Cummings — the same man who had warned Mother Gertrude during Poor Little Rich Girl two years earlier that it was time for the studio to find better stories for Shirley, now that she had lost “that baby quality”. I doubt if this is what he had in mind. Shirley is ten now — or nine, depending on which version of her birth certificate people believed. In any case, she’s too old to be mistaking the “I Want You!” Uncle Sam for somebody’s real uncle who happens to go by that name. Conversely, she’s still too young to be spouting the lick-the-Depression pep talks that Warner Baxter once declaimed in Stand Up and Cheer!

Shirley remembered that her mother became alarmed at the trend of her recent pictures, not only the decreasing budgets, but the sameness of Shirley’s roles. As Shirley remembered it, her mother met with Zanuck and “expressed the opinion that recent scripts were forcing me into rigid, stereotyped roles inappropriate to my growth.” Zanuck countered that the public didn’t want their stars to change. “Now she’s lovable…The less she changes, the longer she lasts.”

Just Around the Corner wasn’t a dead loss. It’s worth seeing for, if nothing else, Shirley’s final teaming with Bill Robinson. Their last number together, “I Love to Walk in the Rain” (by Walter Bullock and Harold Spina), was a bit anticlimactic; more their style was an earlier number, “This Is a Happy Little Ditty”, in which they’re joined by Joan Davis and Bert Lahr. Their dance here looks more like Bojangles’s work and less like that of credited dance directors Nick Castle and Geneva Sawyer. Note especially Bojangles’s truckin’-on-down entrance into the number — that man could dance down a staircase like nobody’s business! (Note also, earlier in the number, when Shirley and Joan Davis get out of step with each other. Now there’s a typical B-movie touch for you: either nobody noticed, or they didn’t bother to retake it so Joan and Shirley could get it right.)

The unsigned review in Variety was surprisingly positive (“topflight for general all-around entertainment”), but conceded, “Youngster is unquestionably getting more mature, and in growing older, Shirley seems to be under stress of acting rather than being natural.” At the Times, Frank Nugent was biting:

Fee-fi-fo-fum, and a couple of ho-hums. Shirley Temple is at the Roxy in “Just Around the Corner” and that’s where we’re lurking with a cleaver in one hand and a lollypop [sic] in the other…Shirley is not responsible, of course. No child could conceive so diabolic a form of torture. There must be an adult mind in back of it all — way, way in back of it all.

And we’ll leave the picture with those two swings of the critical pendulum.

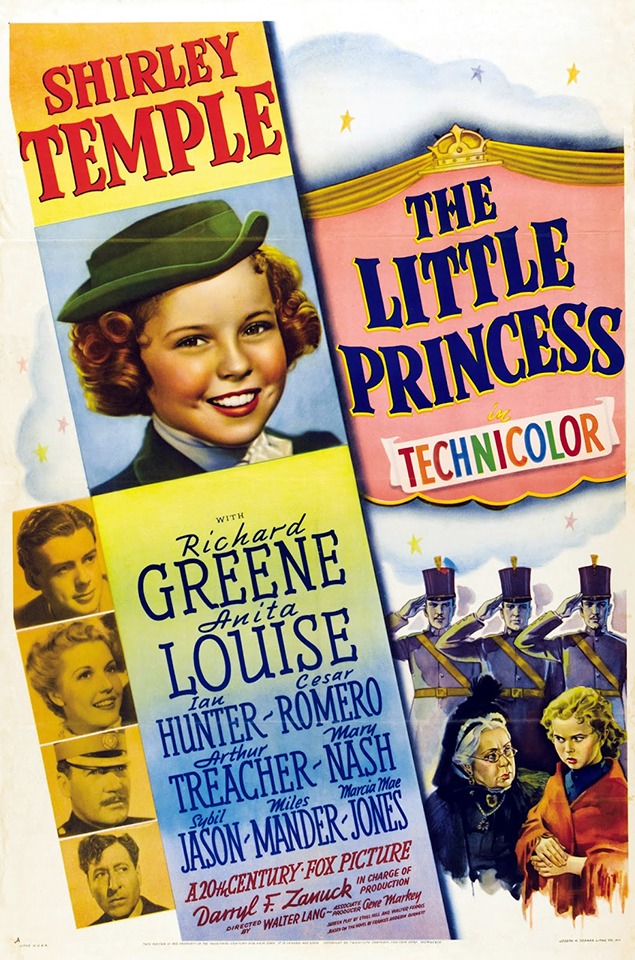

Next time out, Shirley would be restored to the undeniable ranks of Fox’s A-pictures. No expense would be spared — including, for the first time since the final seconds of The Little Colonel, the use of Technicolor.

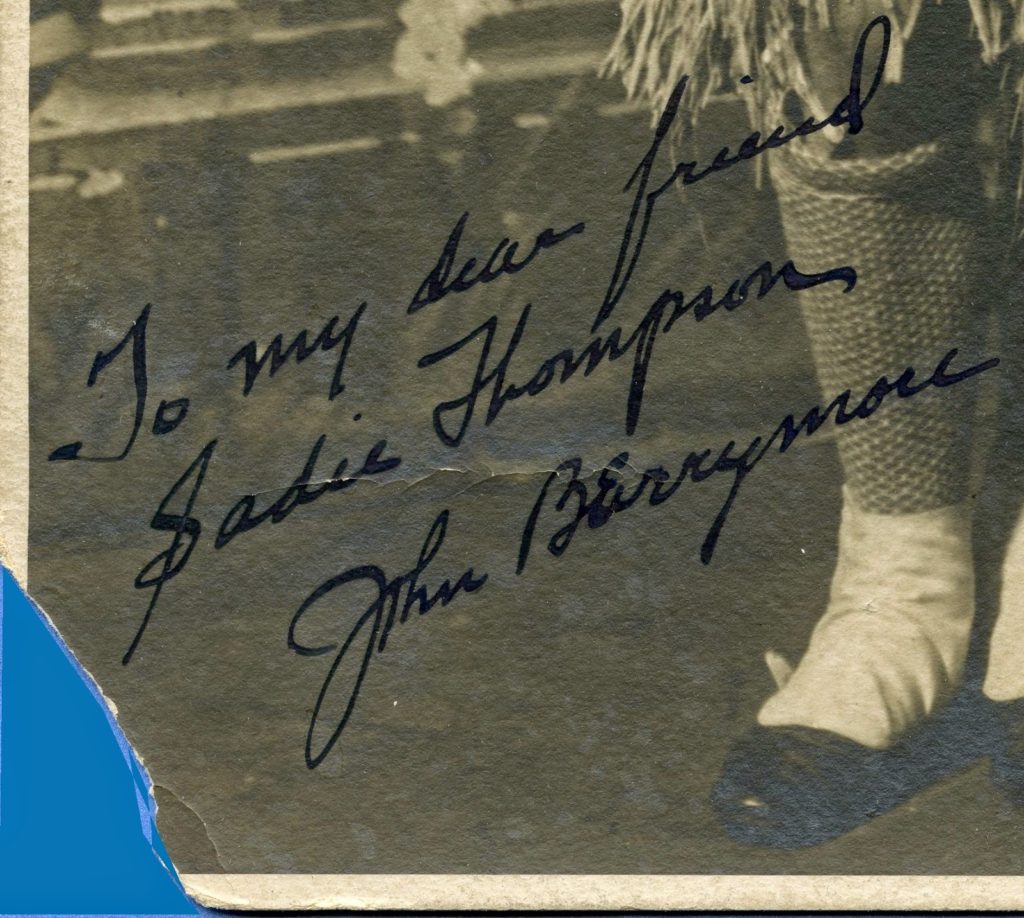

Today I received this picture from historian Richard M. Roberts, who states conclusively — and I’m convinced — that my picture isn’t John Barrymore after all. Richard’s message:

Today I received this picture from historian Richard M. Roberts, who states conclusively — and I’m convinced — that my picture isn’t John Barrymore after all. Richard’s message:

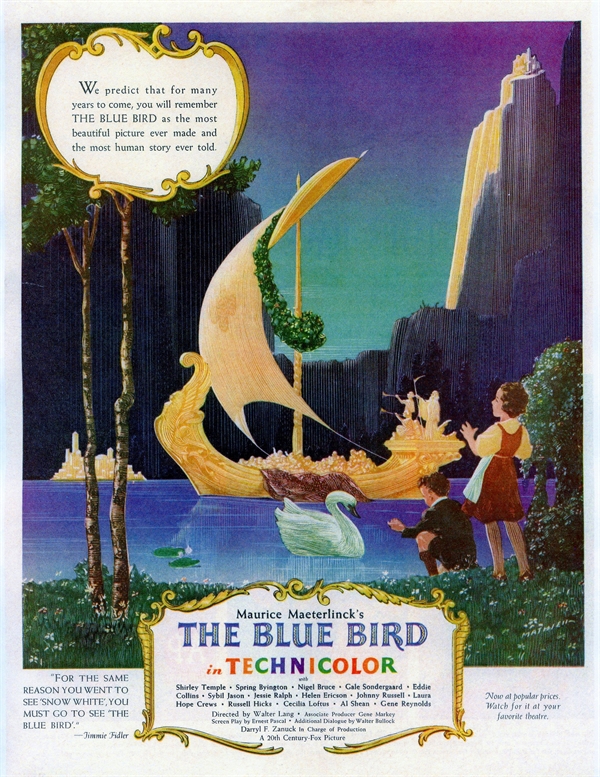

The Blue Bird was Shirley’s second brush with a Nobel Prize winner, after Rudyard Kipling and Wee Willie Winkie. Belgian poet, essayist and playwright Maurice Maeterlinck (1862-1949) was a leading proponent of the Symbolist movement in European art and literature of the late 19th century. His most influential and commercially successful play was probably Pelleas and Melisande (1893), a doomed-lovers tragedy that inspired numerous operas, all of which are performed these days far more often than the original play.

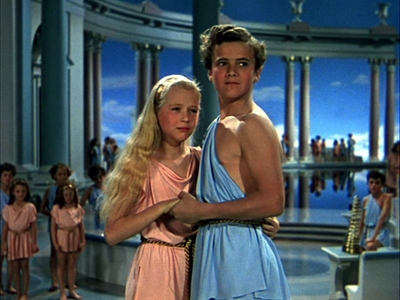

The Blue Bird was Shirley’s second brush with a Nobel Prize winner, after Rudyard Kipling and Wee Willie Winkie. Belgian poet, essayist and playwright Maurice Maeterlinck (1862-1949) was a leading proponent of the Symbolist movement in European art and literature of the late 19th century. His most influential and commercially successful play was probably Pelleas and Melisande (1893), a doomed-lovers tragedy that inspired numerous operas, all of which are performed these days far more often than the original play. Or trying to. The Blue Bird‘s greatest faults are inherent in Maeterlinck’s play; this was one case where Fox might have been justified in jettisoning everything but the title. Instead, Ernest Pascal’s script made an honest effort (with moderate success) to streamline, simplify and motivate the wild excesses of Maeterlinck’s fantasy. First, merely as a practical matter, the birth order of the lead siblings was reversed, making Mytyl (Shirley) the older and Tyltyl (Johnny Russell) the younger. The size of their expedition was streamlined, with their only companions being the cat Tylette (Gale Sondergaard, right) and dog Tylo (Eddie Collins, next to her). Of Maeterlinck’s five spirits, only Light remained (played by Helen Ericson), and she served, logically enough, as the children’s guide on their quest. (The group is shown here as they set out, with Jessie Ralph as Berylune on the left.)

Or trying to. The Blue Bird‘s greatest faults are inherent in Maeterlinck’s play; this was one case where Fox might have been justified in jettisoning everything but the title. Instead, Ernest Pascal’s script made an honest effort (with moderate success) to streamline, simplify and motivate the wild excesses of Maeterlinck’s fantasy. First, merely as a practical matter, the birth order of the lead siblings was reversed, making Mytyl (Shirley) the older and Tyltyl (Johnny Russell) the younger. The size of their expedition was streamlined, with their only companions being the cat Tylette (Gale Sondergaard, right) and dog Tylo (Eddie Collins, next to her). Of Maeterlinck’s five spirits, only Light remained (played by Helen Ericson), and she served, logically enough, as the children’s guide on their quest. (The group is shown here as they set out, with Jessie Ralph as Berylune on the left.) There follows another departure from Maeterlinck. After they escape from The Luxurys, the children must pass through a great forest. Tylette, hoping to rid herself of the children and thus gain her freedom, runs ahead of them and incites the trees (represented by Edwin Maxwell, Sterling Holloway and others) to avenge themselves on the children of the woodcutter who is always chopping them down. The trees take the bait, even calling on their old enemies lightning and fire — so eager are they to destroy the children that they willingly immolate themselves in a great forest fire. Tylette, however, has outsmarted herself; trying to lure the children to their doom, she is herself burned to death, and only the courageous efforts of the loyal Tylo enables the children to escape to safety.

There follows another departure from Maeterlinck. After they escape from The Luxurys, the children must pass through a great forest. Tylette, hoping to rid herself of the children and thus gain her freedom, runs ahead of them and incites the trees (represented by Edwin Maxwell, Sterling Holloway and others) to avenge themselves on the children of the woodcutter who is always chopping them down. The trees take the bait, even calling on their old enemies lightning and fire — so eager are they to destroy the children that they willingly immolate themselves in a great forest fire. Tylette, however, has outsmarted herself; trying to lure the children to their doom, she is herself burned to death, and only the courageous efforts of the loyal Tylo enables the children to escape to safety.  …the Kingdom of the Future, where (returning to Maeterlinck’s text) Mytyl and Tyltyl find countless children are waiting to be born. In this remarkable scene, which looks like something designed by Maxfield Parrish, Mytyl and Tyltyl wander among the eager throng, so amazed at what they see that they completely forget to look for the Blue Bird. They meet a little girl who joyfully greets them by name (Ann Todd, not to be confused with the British actress of the same name), telling them that she will be their little sister, “in a year perhaps.” Then she adds sadly, “I’ll only be with you a little while.” Mytyl and Tyltyl wander among children who are preparing for what will be their calling in life. One boy proudly displays the anesthetic he will discover; another tinkers with an electric light. Still another, solitary and melancholy, tells them his destiny is to fight against slavery, injustice and inequality — but people “won’t listen…they’ll destroy me.”

…the Kingdom of the Future, where (returning to Maeterlinck’s text) Mytyl and Tyltyl find countless children are waiting to be born. In this remarkable scene, which looks like something designed by Maxfield Parrish, Mytyl and Tyltyl wander among the eager throng, so amazed at what they see that they completely forget to look for the Blue Bird. They meet a little girl who joyfully greets them by name (Ann Todd, not to be confused with the British actress of the same name), telling them that she will be their little sister, “in a year perhaps.” Then she adds sadly, “I’ll only be with you a little while.” Mytyl and Tyltyl wander among children who are preparing for what will be their calling in life. One boy proudly displays the anesthetic he will discover; another tinkers with an electric light. Still another, solitary and melancholy, tells them his destiny is to fight against slavery, injustice and inequality — but people “won’t listen…they’ll destroy me.”

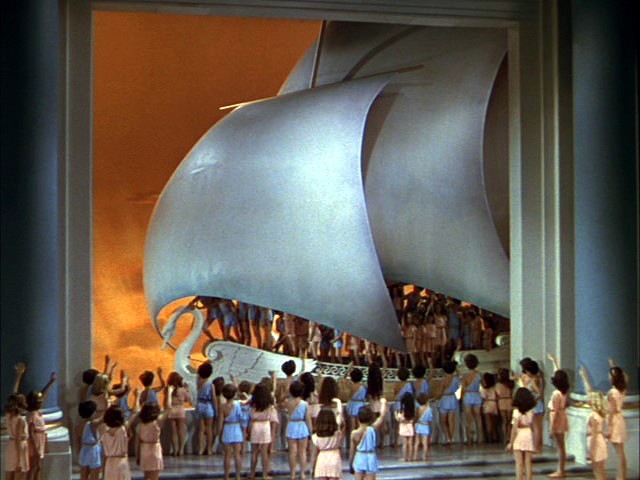

The children whose time has come board a graceful alabaster ship with silver sails and the figurehead of a swan. As the boat pulls away from the quay into a golden sea and sky, the children left behind, still awaiting their turn, bid their friends a joyous bon voyage. The departing passengers fix their eyes on the far horizon, and they sing:

The children whose time has come board a graceful alabaster ship with silver sails and the figurehead of a swan. As the boat pulls away from the quay into a golden sea and sky, the children left behind, still awaiting their turn, bid their friends a joyous bon voyage. The departing passengers fix their eyes on the far horizon, and they sing:

Unlike Lady Jane, A Little Princess has never been out of print since it was first published in 1905. It was the work of Frances Hodgson Burnett, who was born in England in 1849 but lived much of her adult life in the U.S., where she became a citizen in 1905, and where she died and was buried in 1924. She began writing short fiction for magazines while still in her teens, later progressing to romantic novels for adults and sentimental books for children. Her books sold well all her life, enabling her to support a transatlantic lifestyle with homes at various times in America, in England and on the Continent. Her adult novels were all popular in their day, but it’s for her children’s books that she remains best remembered, specifically Little Lord Fauntleroy (1885), The Secret Garden (1911) and A Little Princess.

Unlike Lady Jane, A Little Princess has never been out of print since it was first published in 1905. It was the work of Frances Hodgson Burnett, who was born in England in 1849 but lived much of her adult life in the U.S., where she became a citizen in 1905, and where she died and was buried in 1924. She began writing short fiction for magazines while still in her teens, later progressing to romantic novels for adults and sentimental books for children. Her books sold well all her life, enabling her to support a transatlantic lifestyle with homes at various times in America, in England and on the Continent. Her adult novels were all popular in their day, but it’s for her children’s books that she remains best remembered, specifically Little Lord Fauntleroy (1885), The Secret Garden (1911) and A Little Princess.

Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm was another of Shirley’s “no trace” pictures, like

Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm was another of Shirley’s “no trace” pictures, like  Little Miss Broadway was the one Shirley called “unfailingly bland”, and that about sums it up. Shirley is once again an orphan, this time moving from her orphanage to live with a friend of her late parents (Edward Ellis) who runs a hotel for entertainers. The curmudgeon this time is the rich old landlady next door (Edna May Oliver, her middle name misspelled as “Mae”), who not only plots to get rid of those unsavory show people by selling their hotel out from under them, but (channeling Sara Haden’s truant officer from Captain January) moves to have Shirley returned to her orphanage. Meanwhile, her playboy nephew (George Murphy) is charmed by Shirley and smitten with Ellis’s daughter (Phyllis Brooks of Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm) and tries to thwart the old girl. It all ends in the courtroom of judge Claude Gillingwater, with Shirley and her troupers proving that they’ve got a moneymaking show on their hands and can afford to keep the hotel open.

Little Miss Broadway was the one Shirley called “unfailingly bland”, and that about sums it up. Shirley is once again an orphan, this time moving from her orphanage to live with a friend of her late parents (Edward Ellis) who runs a hotel for entertainers. The curmudgeon this time is the rich old landlady next door (Edna May Oliver, her middle name misspelled as “Mae”), who not only plots to get rid of those unsavory show people by selling their hotel out from under them, but (channeling Sara Haden’s truant officer from Captain January) moves to have Shirley returned to her orphanage. Meanwhile, her playboy nephew (George Murphy) is charmed by Shirley and smitten with Ellis’s daughter (Phyllis Brooks of Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm) and tries to thwart the old girl. It all ends in the courtroom of judge Claude Gillingwater, with Shirley and her troupers proving that they’ve got a moneymaking show on their hands and can afford to keep the hotel open. If Little Miss Broadway was an A-minus picture, Just Around the Corner was no more than a B-plus. If that. Shirley plays Penny Hale, who is taken out of private school when her widowed architect father (Charles Farrell) loses his job, and consequently the penthouse he and Penny have been living in, as well as the money to pay for her school. He’s now forced to work as the electrician in the apartment building where they formerly occupied the penthouse, and he and Penny must now make do with a tiny apartment in the basement.

If Little Miss Broadway was an A-minus picture, Just Around the Corner was no more than a B-plus. If that. Shirley plays Penny Hale, who is taken out of private school when her widowed architect father (Charles Farrell) loses his job, and consequently the penthouse he and Penny have been living in, as well as the money to pay for her school. He’s now forced to work as the electrician in the apartment building where they formerly occupied the penthouse, and he and Penny must now make do with a tiny apartment in the basement. So far we’ve taken Shirley up to the middle of 1937. She’s been Hollywood’s top box-office star for two years, and she’ll go on to be for two years more. This is probably a good time to deal with one of Hollywood’s most persistent and tantalizing legends: Is it true that Shirley Temple was originally set to play Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz? The short answer is: No, but there may be a complicated grain of truth to the legend. In fact, given Shirley’s stature in the industry during the mid-to-late 1930s, it’s unlikely that there wouldn’t be something to it.

So far we’ve taken Shirley up to the middle of 1937. She’s been Hollywood’s top box-office star for two years, and she’ll go on to be for two years more. This is probably a good time to deal with one of Hollywood’s most persistent and tantalizing legends: Is it true that Shirley Temple was originally set to play Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz? The short answer is: No, but there may be a complicated grain of truth to the legend. In fact, given Shirley’s stature in the industry during the mid-to-late 1930s, it’s unlikely that there wouldn’t be something to it. According to Variety, Heidi was chosen for Shirley by public demand, as expressed in her fan mail — although the showbiz bible may simply have been parroting a studio press release. Either way, the role was a natural for Shirley. The source was a novel by Johanna Spyri (1827-1901), first published in the author’s native Switzerland in 1880. The book was instantly popular, and promptly translated from its original German into virtually every written language on Earth. The book was — and remains — so popular, in fact, that it’s surprising to realize that Shirley’s picture in 1937 was the first attempt to make a movie out of it (there have been over a dozen since).

According to Variety, Heidi was chosen for Shirley by public demand, as expressed in her fan mail — although the showbiz bible may simply have been parroting a studio press release. Either way, the role was a natural for Shirley. The source was a novel by Johanna Spyri (1827-1901), first published in the author’s native Switzerland in 1880. The book was instantly popular, and promptly translated from its original German into virtually every written language on Earth. The book was — and remains — so popular, in fact, that it’s surprising to realize that Shirley’s picture in 1937 was the first attempt to make a movie out of it (there have been over a dozen since).

Then disaster strikes — incredibly enough, in the form of exactly the sort of thing Darryl Zanuck said he didn’t want in Wee Willie Winkie. As Heidi and her grandfather sit at their cabin table, he ostensibly begins reading her a story about “The Magic Wooden Shoes”. The camera moves in on a woodcut in the book, and the picture dissolves to a quaint little Dutch scene by a storybook Zuider Zee, and there’s Shirley — or is it Heidi? — in blonde braids and bangs and a starched cap, singing about her shoes:

Then disaster strikes — incredibly enough, in the form of exactly the sort of thing Darryl Zanuck said he didn’t want in Wee Willie Winkie. As Heidi and her grandfather sit at their cabin table, he ostensibly begins reading her a story about “The Magic Wooden Shoes”. The camera moves in on a woodcut in the book, and the picture dissolves to a quaint little Dutch scene by a storybook Zuider Zee, and there’s Shirley — or is it Heidi? — in blonde braids and bangs and a starched cap, singing about her shoes:  But looking back, we can see the handwriting on the wall. For me, seeing Heidi again for the first time in nearly 60 years was an eye-opening shock. I had remembered it as one of Shirley’s best-loved pictures. In fact, it always perplexed me that the 1952 Swiss version, which I saw about the same time, stayed fresher in my memory over the decades. Seeing Shirley’s again, I’m no longer perplexed. Heidi is no doubt one of her best-loved pictures, but it’s not one of her best. Despite those very good early scenes, and some later ones like the scene where the grandfather accompanies Heidi to the church that he hasn’t visited in years (straight out of Frau Spyri’s novel), the picture never recovers from the miscalculation of “In Our Little Wooden Shoes”; it’s one of the head-scratching what-on-Earth-were-they-thinking moments of 1930s Hollywood. What they were thinking, I suspect — or more to the point, what Darryl Zanuck was thinking — was that his dictum about writing the story as if it were a Little Women or David Copperfield, about writing for Shirley as an actress and not depending on any of her tricks, was no longer operative. Henceforth, as far as 20th Century Fox was concerned, Shirley’s tricks would be her stock in trade. The studio was no longer interested in Shirley becoming an actress; instead, they would keep her a baby taking a bow for as long as they could get away with it.

But looking back, we can see the handwriting on the wall. For me, seeing Heidi again for the first time in nearly 60 years was an eye-opening shock. I had remembered it as one of Shirley’s best-loved pictures. In fact, it always perplexed me that the 1952 Swiss version, which I saw about the same time, stayed fresher in my memory over the decades. Seeing Shirley’s again, I’m no longer perplexed. Heidi is no doubt one of her best-loved pictures, but it’s not one of her best. Despite those very good early scenes, and some later ones like the scene where the grandfather accompanies Heidi to the church that he hasn’t visited in years (straight out of Frau Spyri’s novel), the picture never recovers from the miscalculation of “In Our Little Wooden Shoes”; it’s one of the head-scratching what-on-Earth-were-they-thinking moments of 1930s Hollywood. What they were thinking, I suspect — or more to the point, what Darryl Zanuck was thinking — was that his dictum about writing the story as if it were a Little Women or David Copperfield, about writing for Shirley as an actress and not depending on any of her tricks, was no longer operative. Henceforth, as far as 20th Century Fox was concerned, Shirley’s tricks would be her stock in trade. The studio was no longer interested in Shirley becoming an actress; instead, they would keep her a baby taking a bow for as long as they could get away with it.  Calling the picture “Rudyard Kipling’s” Wee Willie Winkie was a bit of an overstatement. The original story was published in 1888, when the future Nobel Prize winner was 22. It told of Percival William Williams, the six-year-old son of an army colonel stationed with his regiment in British India at the foot of the Khyber Pass on the indistinct border with Afghanistan. Percival has a penchant for nicknaming people, including himself, so he has adopted the name Wee Willie Winkie from one of his nursery-books. Winkie is bright but typically mischievous for a boy his age, and under the military discipline imposed by his father he is forever earning, then forfeiting, a succession of Good Conduct Badges.

Calling the picture “Rudyard Kipling’s” Wee Willie Winkie was a bit of an overstatement. The original story was published in 1888, when the future Nobel Prize winner was 22. It told of Percival William Williams, the six-year-old son of an army colonel stationed with his regiment in British India at the foot of the Khyber Pass on the indistinct border with Afghanistan. Percival has a penchant for nicknaming people, including himself, so he has adopted the name Wee Willie Winkie from one of his nursery-books. Winkie is bright but typically mischievous for a boy his age, and under the military discipline imposed by his father he is forever earning, then forfeiting, a succession of Good Conduct Badges. Needless to say, in Ernest Pascal and Julien Josephson’s screenplay nearly all of this was changed. Percival was changed to Priscilla and given a widowed American mother (June Lang). The colonel backs up a generation, becoming Priscilla’s grandfather (C. Aubrey Smith), who sends for Priscilla and her mother when he learns they are living in poverty in America. Priscilla is still nicknamed Wee Willie Winkie, but her military discipline is self-imposed in an effort to become a soldier, since that seems to be the only type of person her grandfather the colonel likes. “Private” Winkie still takes a shine to Lt. “Coppy” Brandis (Michael Whalen, Shirley’s father in Poor Little Rich Girl), but he throws over Maj. Allardyce’s daughter to romance Winkie’s mother. While he’s doing that, Coppy’s duties as Winkie’s best friend among the soldiery devolve onto a new character, Sergeant MacDuff (Victor McLaglen).

Needless to say, in Ernest Pascal and Julien Josephson’s screenplay nearly all of this was changed. Percival was changed to Priscilla and given a widowed American mother (June Lang). The colonel backs up a generation, becoming Priscilla’s grandfather (C. Aubrey Smith), who sends for Priscilla and her mother when he learns they are living in poverty in America. Priscilla is still nicknamed Wee Willie Winkie, but her military discipline is self-imposed in an effort to become a soldier, since that seems to be the only type of person her grandfather the colonel likes. “Private” Winkie still takes a shine to Lt. “Coppy” Brandis (Michael Whalen, Shirley’s father in Poor Little Rich Girl), but he throws over Maj. Allardyce’s daughter to romance Winkie’s mother. While he’s doing that, Coppy’s duties as Winkie’s best friend among the soldiery devolve onto a new character, Sergeant MacDuff (Victor McLaglen).

Seen today, Wee Willie Winkie bears out Shirley’s opinion more than it does Mosher’s, Flin’s or Nugent’s. The picture is certainly not too long. Children may squirm during the protracted love scenes between Michael Whalen and June Lang, but so do adults. Both were bland Fox contract players on an unstoppable career path toward B pictures and, at the onset of middle age, television. Whalen’s dark good looks were about to be rendered irrelevant by the rise of the far more charismatic Tyrone Power. As for Lang (Shirley’s “mother” was only 11 years older than she was), within seven years she would be a nameless, uncredited “Goldwyn Girl” behind Danny Kaye in Up in Arms, and would finish her career with one-off guest shots on TV cop shows in the ’50s and ’60s. Whalen and Lang were (and remain) attractive and inoffensive, but they lack the chemistry — with either the audience or each other — that Robert Young and Alice Faye showed in Stowaway, or Faye and Jack Haley in Poor Little Rich Girl. (The blue-green of this frame-cap, like the sepia of others, reproduces the tinted stock Wee Willie Winkie sported on its original release.)

Seen today, Wee Willie Winkie bears out Shirley’s opinion more than it does Mosher’s, Flin’s or Nugent’s. The picture is certainly not too long. Children may squirm during the protracted love scenes between Michael Whalen and June Lang, but so do adults. Both were bland Fox contract players on an unstoppable career path toward B pictures and, at the onset of middle age, television. Whalen’s dark good looks were about to be rendered irrelevant by the rise of the far more charismatic Tyrone Power. As for Lang (Shirley’s “mother” was only 11 years older than she was), within seven years she would be a nameless, uncredited “Goldwyn Girl” behind Danny Kaye in Up in Arms, and would finish her career with one-off guest shots on TV cop shows in the ’50s and ’60s. Whalen and Lang were (and remain) attractive and inoffensive, but they lack the chemistry — with either the audience or each other — that Robert Young and Alice Faye showed in Stowaway, or Faye and Jack Haley in Poor Little Rich Girl. (The blue-green of this frame-cap, like the sepia of others, reproduces the tinted stock Wee Willie Winkie sported on its original release.)

I’m going to pass over Dimples as quickly as duty will allow because, like

I’m going to pass over Dimples as quickly as duty will allow because, like  In Child Star Shirley remembered Frank Morgan’s tireless efforts to upstage her and steal focus during their scenes — fiddling with his cuffs, flourishing his handkerchief, placing his stovepipe hat on a table between her and the camera so that she couldn’t be in the shot without stepping off her mark and out of the light. (“Both of us knew perfectly well what he was doing. There was no way I could cope, short of biting at his fingers.”) Director William A. Seiter was on to Morgan’s tricks too; in this scene, where Dimples sings “Picture Me Without You” (one of four pleasantly forgettable songs provided by Jimmy McHugh and Ted Koehler), Seiter made Morgan sit in a chair with his back to the camera. (“When this picture is over,” cracked producer Nunnally Johnson, “either Shirley will have acquired a taste for Scotch whiskey or Frank will come out with curls.”)

In Child Star Shirley remembered Frank Morgan’s tireless efforts to upstage her and steal focus during their scenes — fiddling with his cuffs, flourishing his handkerchief, placing his stovepipe hat on a table between her and the camera so that she couldn’t be in the shot without stepping off her mark and out of the light. (“Both of us knew perfectly well what he was doing. There was no way I could cope, short of biting at his fingers.”) Director William A. Seiter was on to Morgan’s tricks too; in this scene, where Dimples sings “Picture Me Without You” (one of four pleasantly forgettable songs provided by Jimmy McHugh and Ted Koehler), Seiter made Morgan sit in a chair with his back to the camera. (“When this picture is over,” cracked producer Nunnally Johnson, “either Shirley will have acquired a taste for Scotch whiskey or Frank will come out with curls.”)

Stowaway gave Shirley an exotic setting, a story that didn’t require her to carry the show all by herself, and cast-mates who were strong enough to share the load. Shirley played Barbara Stewart, nicknamed “Ching-Ching”, the orphaned daughter of missionaries in Sanchow, China. At the approach of bandits from the hills, she’s about to be orphaned again — or worse — because her guardians the Kruikshanks (also missionaries) refuse to flee from the approaching marauders. Defying them, the wise local magistrate Sun Lo (Philip Ahn) spirits Ching-Ching away with a boatman to Shanghai.

Stowaway gave Shirley an exotic setting, a story that didn’t require her to carry the show all by herself, and cast-mates who were strong enough to share the load. Shirley played Barbara Stewart, nicknamed “Ching-Ching”, the orphaned daughter of missionaries in Sanchow, China. At the approach of bandits from the hills, she’s about to be orphaned again — or worse — because her guardians the Kruikshanks (also missionaries) refuse to flee from the approaching marauders. Defying them, the wise local magistrate Sun Lo (Philip Ahn) spirits Ching-Ching away with a boatman to Shanghai.

Alice also sang “One Never Knows, Does One?”, another one by Gordon and Revel, this time with no little-girl version for Shirley. Then Shirley closed out the show with “That’s What I Want for Christmas”, written by the uncredited Gerald Marks and Irving Caesar. This last number comes at the very end, after the story has been brought to a satisfying conclusion, and it plays almost like a curtain-call encore. Evidently it was added at the last minute to exploit the movie’s holiday engagement at New York’s Roxy picture palace (it didn’t sift down to the rest of the country until after the turn of 1937).

Alice also sang “One Never Knows, Does One?”, another one by Gordon and Revel, this time with no little-girl version for Shirley. Then Shirley closed out the show with “That’s What I Want for Christmas”, written by the uncredited Gerald Marks and Irving Caesar. This last number comes at the very end, after the story has been brought to a satisfying conclusion, and it plays almost like a curtain-call encore. Evidently it was added at the last minute to exploit the movie’s holiday engagement at New York’s Roxy picture palace (it didn’t sift down to the rest of the country until after the turn of 1937).

Don’t be misled by the picture’s title as it appears on the cover of the sheet music below (and on several of the posters and lobby cards); the title was Poor Little Rich Girl, with no “The“. Poor Little Rich Girl has a distinction it shares with Our Little Girl: They are the only two pictures from Shirley’s reign as Fox’s box-office queen (before and after the merger) that are not available on DVD; both can be seen only on out-of-print colorized VHS tapes.

Don’t be misled by the picture’s title as it appears on the cover of the sheet music below (and on several of the posters and lobby cards); the title was Poor Little Rich Girl, with no “The“. Poor Little Rich Girl has a distinction it shares with Our Little Girl: They are the only two pictures from Shirley’s reign as Fox’s box-office queen (before and after the merger) that are not available on DVD; both can be seen only on out-of-print colorized VHS tapes.

The creation of 20th Century Fox was announced as a merger, but it was really a friendly takeover. Darryl Zanuck (former production head at Warner Bros.) and Joseph Schenck (former president of United Artists) had formed 20th Century Pictures in 1933 as an independent concern, renting equipment and studio-and-office space from UA. In two years 20th Century had produced 18 pictures, all but one of which had made money, and several of which had made quite a lot: Folies Bergere de Paris, The House of Rothschild, The Affairs of Cellini, The Call of the Wild, Les Miserables, etc. But Zanuck got his hackles up when UA wouldn’t sell any of its stock to 20th Century, and he started looking around.

The creation of 20th Century Fox was announced as a merger, but it was really a friendly takeover. Darryl Zanuck (former production head at Warner Bros.) and Joseph Schenck (former president of United Artists) had formed 20th Century Pictures in 1933 as an independent concern, renting equipment and studio-and-office space from UA. In two years 20th Century had produced 18 pictures, all but one of which had made money, and several of which had made quite a lot: Folies Bergere de Paris, The House of Rothschild, The Affairs of Cellini, The Call of the Wild, Les Miserables, etc. But Zanuck got his hackles up when UA wouldn’t sell any of its stock to 20th Century, and he started looking around.

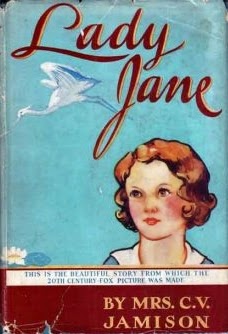

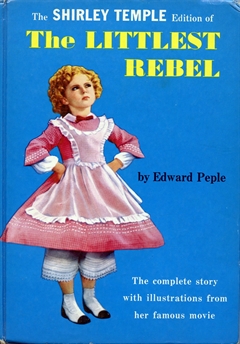

Shirley’s first picture to bear the new 20th Century Fox logo (with its now-famous fanfare) had been in the works before the merger, as the cover of this sheet music suggests. The ostensible source was a play by Edward Peple that ran for 55 performances on Broadway in the winter of 1911-12 before embarking on a long and prosperous tour, making a child star of the ill-fated

Shirley’s first picture to bear the new 20th Century Fox logo (with its now-famous fanfare) had been in the works before the merger, as the cover of this sheet music suggests. The ostensible source was a play by Edward Peple that ran for 55 performances on Broadway in the winter of 1911-12 before embarking on a long and prosperous tour, making a child star of the ill-fated  The Littlest Rebel was aimed at duplicating the success of The Little Colonel; in fact, it surpassed it, and was one of Shirley’s smoothest pictures. The only thing that really dates it today — and it dates it terribly — is the racial attitude I mentioned in my notes on The Little Colonel. That attitude is even more glaring and uncomfortable in The Littlest Rebel because the picture deals directly with the Civil War itself. When Edward Peple wrote his play in 1914, the war was well within human memory; even by the time the movie was made, that generation had not yet passed away (three years later, in 1938, the 75th anniversary of the battle of Gettysburg would occasion a reunion of nearly 1,900 Civil War veterans). The Old South with its genteel planter aristocracy and loyal, happy, contented slaves was an article of faith in the Myth of the Lost Cause, one that died hard and bitterly, and it’s on full display in The Littlest Rebel. It’s difficult to argue with modern viewers who find it just too hard to take. (Shirley even plays one scene in blackface disguise, though at least we are spared the sorry spectacle of hearing her speak with a “darkie” accent.)

The Littlest Rebel was aimed at duplicating the success of The Little Colonel; in fact, it surpassed it, and was one of Shirley’s smoothest pictures. The only thing that really dates it today — and it dates it terribly — is the racial attitude I mentioned in my notes on The Little Colonel. That attitude is even more glaring and uncomfortable in The Littlest Rebel because the picture deals directly with the Civil War itself. When Edward Peple wrote his play in 1914, the war was well within human memory; even by the time the movie was made, that generation had not yet passed away (three years later, in 1938, the 75th anniversary of the battle of Gettysburg would occasion a reunion of nearly 1,900 Civil War veterans). The Old South with its genteel planter aristocracy and loyal, happy, contented slaves was an article of faith in the Myth of the Lost Cause, one that died hard and bitterly, and it’s on full display in The Littlest Rebel. It’s difficult to argue with modern viewers who find it just too hard to take. (Shirley even plays one scene in blackface disguise, though at least we are spared the sorry spectacle of hearing her speak with a “darkie” accent.)

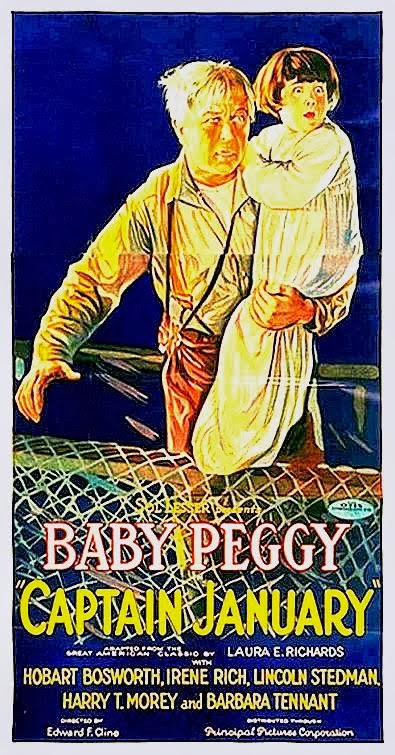

Captain January seems to have a special place in the hearts of Baby Boomers of a Certain Age, perhaps because it was one of Shirley Temple’s first features to go into television syndication in the 1950s. The source material was an 1891 novella by Laura E. Richards. Born Laura Elizabeth Howe in 1850, Mrs. Richards was the daughter of Julia Ward Howe, author of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”. A prolific author in her own right, Mrs. Richards wrote over 90 books, including, with her sister Maud Howe Elliott, a biography of their mother that won them a Pulitzer Prize in 1917. Mrs. Richards also wrote the children’s nonsense poem “Eletelephony” (“Once there was an elephant,/Who tried to use the telephant –/No! No! I mean an elephone,/Who tried to use the telephone…”). Unlike the authors of The Little Colonel and The Littlest Rebel, she lived long enough to see two movies made from her modest little story, dying in 1943 at 92. Whether she saw either movie, or what she thought of them, is not recorded.

Captain January seems to have a special place in the hearts of Baby Boomers of a Certain Age, perhaps because it was one of Shirley Temple’s first features to go into television syndication in the 1950s. The source material was an 1891 novella by Laura E. Richards. Born Laura Elizabeth Howe in 1850, Mrs. Richards was the daughter of Julia Ward Howe, author of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”. A prolific author in her own right, Mrs. Richards wrote over 90 books, including, with her sister Maud Howe Elliott, a biography of their mother that won them a Pulitzer Prize in 1917. Mrs. Richards also wrote the children’s nonsense poem “Eletelephony” (“Once there was an elephant,/Who tried to use the telephant –/No! No! I mean an elephone,/Who tried to use the telephone…”). Unlike the authors of The Little Colonel and The Littlest Rebel, she lived long enough to see two movies made from her modest little story, dying in 1943 at 92. Whether she saw either movie, or what she thought of them, is not recorded.

Our Little Girl

Our Little Girl  Curly Top

Curly Top  But like the story, the supporting players (Boles; Hudson; Jane Darwell and Rafaela Ottiano as matrons at the orphanage; Esther Dale as Boles’s aunt; Billy Gilbert and Arthur Treacher as his cook and butler) were all beside the point. Shirley was just about the whole show. She is even the focus of both Boles’s songs. After singing “It’s All So New to Me”, while the orchestra wafts on in the background, he strolls around his palatial drawing room, where he fancies Shirley beaming down at him from the paintings on the walls…

But like the story, the supporting players (Boles; Hudson; Jane Darwell and Rafaela Ottiano as matrons at the orphanage; Esther Dale as Boles’s aunt; Billy Gilbert and Arthur Treacher as his cook and butler) were all beside the point. Shirley was just about the whole show. She is even the focus of both Boles’s songs. After singing “It’s All So New to Me”, while the orchestra wafts on in the background, he strolls around his palatial drawing room, where he fancies Shirley beaming down at him from the paintings on the walls…