Chapter II of Glamour Boys is now published. Look under the Fiction menu, or click here to go directly without having to scroll down through Chapter I.

Again, I hope it meets with your approval…

Chapter II of Glamour Boys is now published. Look under the Fiction menu, or click here to go directly without having to scroll down through Chapter I.

Again, I hope it meets with your approval…

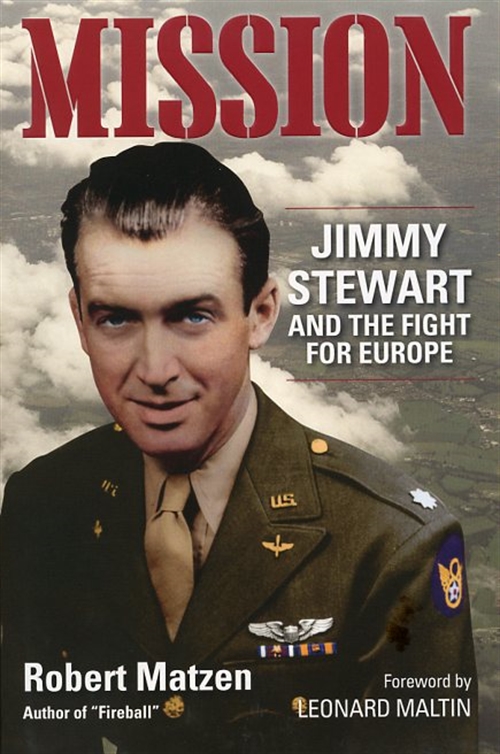

I’m preparing a post now on Clara Bow’s career in talking pictures, a career that was longer and more estimable than posterity has given her credit for. Well, as so often happens here at Cinedrome, that post is growing and deepening as I work on it, and has been accordingly delayed. But it has to go on a back burner for now in any case, because my friend Robert Matzen is about to publish his latest book. It’s one that belongs on the bookshelf of every Cinedrome reader — and a lot of other bookshelves besides. This new book not only goes a long way to fill a decades-old gap in our knowledge of the life and times of one of America’s most beloved movie stars, it also adds significantly to our knowledge — at least it added to mine — of the rigors and terrors of aerial warfare during World War II.

I’m preparing a post now on Clara Bow’s career in talking pictures, a career that was longer and more estimable than posterity has given her credit for. Well, as so often happens here at Cinedrome, that post is growing and deepening as I work on it, and has been accordingly delayed. But it has to go on a back burner for now in any case, because my friend Robert Matzen is about to publish his latest book. It’s one that belongs on the bookshelf of every Cinedrome reader — and a lot of other bookshelves besides. This new book not only goes a long way to fill a decades-old gap in our knowledge of the life and times of one of America’s most beloved movie stars, it also adds significantly to our knowledge — at least it added to mine — of the rigors and terrors of aerial warfare during World War II.

This is the book: Mission: Jimmy Stewart and the Fight for Europe. Robert Matzen, Cinedrome readers will recall, is the author of Fireball: Carole Lombard and the Tragedy of Flight 3, a riveting page-turner about the death of Carole Lombard, who became the first celebrity casualty of World War II when her plane crashed on the way home from a war bond rally in Indiana. Mission tells us, in harrowing detail, how close James Stewart — Hollywood’s “boy next door” and an Oscar winner for 1940’s The Philadelphia Story — came to becoming another casualty of that same war. And not in a stateside bond tour, but in combat in the skies over Germany.

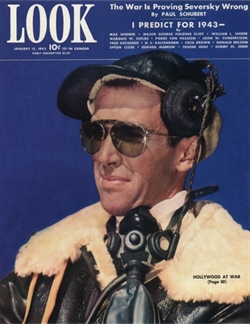

It’s common knowledge that James Stewart is one of the greatest stars in the history of Hollywood; in the American Film Institute’s 1999 list of the screen’s 50 greatest legends, he ranked third among men behind Humphrey Bogart and Cary Grant. Less commonly known is that he was the highest-ranking actor in military history (not counting Ronald Reagan’s two terms as Commander in Chief), retiring from the U.S. Air Force Reserve as a brigadier general in 1968. He always kept his screen and military careers carefully separate, especially during the war. There was a flurry of publicity when he enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps in March 1941 (nine months before Pearl Harbor), but that media circus led him to hold the press at arm’s length thereafter, and his military higher-ups generally cooperated by shielding him. Throughout the war, hopeful reporters were often reduced to filing pouty dispatches about how Lt. (later Capt., Maj., Lt. Col. and Col.) Stewart wouldn’t talk to them. And after the war, in the 52 years that remained to him, he spoke sparingly and in the most general terms about his war service. Of his experiences flying bombing missions over France and Germany — aside from a brief stint as a talking head on Thames Television’s documentary series The World at War, identified only as “James Stewart, Squadron Commander” — he spoke hardly at all.

Stewart may have virtually taken the story of his wartime service, and his 20 combat missions in B-17 and B-24 bombers, to his grave, but Robert Matzen has exhumed the bones of the story from official military records and mission reports, and fleshed them out with the diaries, memoirs and recollections of the men who flew with Stewart and others like him, and with his own understanding of aeronautics born of ten years working in communications for NASA. He also gives us a keen insight into the tradition of military service that ran back generations in Jimmy Stewart’s family, something Stewart himself never elaborated on — perhaps because it would sound too much like bragging, perhaps because it was too internalized to bring to the surface.

Stewart may have virtually taken the story of his wartime service, and his 20 combat missions in B-17 and B-24 bombers, to his grave, but Robert Matzen has exhumed the bones of the story from official military records and mission reports, and fleshed them out with the diaries, memoirs and recollections of the men who flew with Stewart and others like him, and with his own understanding of aeronautics born of ten years working in communications for NASA. He also gives us a keen insight into the tradition of military service that ran back generations in Jimmy Stewart’s family, something Stewart himself never elaborated on — perhaps because it would sound too much like bragging, perhaps because it was too internalized to bring to the surface.

Strictly speaking, Jimmy Stewart was actually James Maitland Stewart II (though his birth certificate didn’t put it that way). J.M. the First was his paternal grandfather, a Signal Corps sergeant during the Civil War who rode with Sheridan and Custer in the Shenandoah Valley in 1864, saw action at Cedar Creek, Five Forks and Sailor’s Creek, and was present at Appomattox Court House as Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant. Fifty years later, he would regale young Jim with tales of seeing Lee, Grant, Sheridan, Custer and Lincoln all in the flesh. “This,” Matzen tells us succinctly, “wasn’t history in a book.” (Did young Jim reflect on this family lore in 1938, when he played a Union Army doctor receiving an audience with President Lincoln in Of Human Hearts? How could he not?) Sgt. Stewart also had a brother Archibald who didn’t survive the war, falling at Spotsylvania.

Then there was Jim’s maternal grandfather, Col. Samuel M. Jackson, who fought in the Wheatfield at Gettysburg and helped hold the Federal left on the second day, rising to the rank of general by war’s end. Gen. Jackson died before Jim was born, but his devotion to serving his country remained legendary in the family and mingled with that of Sgt. Stewart and his brother Archie.

And with that of Jim’s own father Alexander. He served briefly in the Spanish-American War but saw no action; he fell ill in Puerto Rico, and that “splendid little war” was over before he recovered. He didn’t give up; 20 years later, age 45 and married with children, he re-enlisted when America entered the Great War and served in France in the Ordnance Repair Dept.

A future in military service for James Stewart the Younger was a foregone conclusion, and he began preparing for it even as he was climbing the ladder to stardom in Hollywood (and, as a playboy bachelor, cutting a swath through Tinsel Town’s female population, amusingly recounted by Matzen). An early fascination with aviation (and hero-worship of Charles Lindbergh, whom he would later play in the movies) made him set his sights on the Army Air Corps, plunging into flying lessons as soon as he could afford them. (Fun Little-Known Fact: James Stewart got his commercial pilot’s license even before his first Oscar nomination.)

When Mission follows Capt. Stewart to combat duty in England, after a frustrating two years stateside training men to face the action he wanted to see, the book becomes an eye-opening chronicle of the nightmare of aerial combat. Robert Matzen puts us on the flight deck and in the bomb bays and gun turrets as vividly as Laura Hillenbrand put us in the saddle in her brilliant Seabiscuit. Reading Mission is as close as you’ll ever want to get to flying at 20,000 feet swaddled in a heated suit against the 40-below weather, icicles dangling from (and occasionally clogging) your oxygen mask, struggling to keep your behemoth plane in formation while anti-aircraft flak rips holes in your fuselage and hundreds of Luftwaffe fighters swarm around you like death-dealing wasps. Twenty times Oscar-winner Stewart went through it — eight, nine, ten hours in the air, never knowing which split-second might be his last. No wonder he never talked about it.

As he did in Fireball, Matzen completes the picture he paints by recounting the experiences of others who lived through the air war over Europe from perspectives of their own. From top to bottom here:

As he did in Fireball, Matzen completes the picture he paints by recounting the experiences of others who lived through the air war over Europe from perspectives of their own. From top to bottom here:

Sgt. Clement Leone of Baltimore, a radio operator in Stewart’s combat wing, who was a senior in high school when Pearl Harbor was attacked, and whose fascination with airplanes, like Stewart’s, channeled him into the Air Corps once he turned 18. Leone’s exploits, especially after being blown out of his exploding plane over German territory, would make a book in themselves. (Non-spoiler alert: Leone survived, came home, and is today alive and well; he was a key source of Robert Matzen’s insight into life in a bomber crew.);

Gen. Adolf Galland (with the moustache) of the Luftwaffe’s fighter wing, who flew hundreds of missions against American bombers, and did not share Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring’s contempt for the Americans and their Flying Fortresses and Liberators; and

The Siepmann family of Wilhelmshaven, later Eppstein near Frankfurt. Papa Hans was a naval engineer working on U-boats. Mama Riele and their children lived through the Allied bombing campaign as civilians cowering in the shadow of those planes overhead; they didn’t share Göring’s contempt either. Their oldest child Gertrud (far left) later married an American G.I. and emigrated to America in 1956. Robert Matzen knew her for years as Trudy McVicker before learning of her childhood in Hitler’s Germany and coaxing her to contribute her memories to Mission.

Whether you’re interested in Jimmy Stewart, Hollywood, World War II, or all three, you want to read Mission. The official publication date is Monday, October 24. You can order the book here from Amazon. And you can learn more about the book here, about stops on the upcoming Mission National Book Tour here, and about Robert Matzen himself here.

Take my advice and don’t let any grass grow under your feet. I won’t be surprised if the first printing sells out.

Today marks the beginning of my first work of new fiction here at Cinedrome; the title is Glamour Boys. Now here, I guess, if I was really good at this sort of thing, I’d launch into some tantalizing inside-flap-of-the-dust-jacket copy describing the story and the characters, hooking and reeling you in like an expert fisherman. But honestly, that’s not really my long suit; I think I’d rather just let Chapter I, and those that follow, speak for themselves. To begin reading, hover on Jim’s Fiction at the top and select the title.

Glamour Boys, I say again, is a work of fiction. The persons, firms and events portrayed therein are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. No identification with any real firms, or with any real persons living or dead, is intended, and none should be inferred.

That said, I hope it meets with your approval…

Welcome to the New! Improved! Cinedrome! As you can see, there’s a new look and a lot of new features. I’ll go over some of them with you now.

First, in the right column:

And up top:

In addition to these, there’s my Links and Resources page, imported from before, and a Contact page for info on how to get in touch with me; it’s always a pleasure to hear from any and all of you.

I’m grateful to my good friend Jean Black at My Big Fat Sites for bringing all this to fruition. I hope you like the new Cinedrome; feel free to look around, make yourself comfortable, and come back often.

Coming up next – Clara Talks!

Sunday, the last day of Cinevent 2016, got off to a vivacious start with a double feature showcasing that most utterly, charmingly, irresistibly delightful of movie stars, Clara Bow. Only the persistent prejudice against silent movies keeps Clara Bow from her rightful place among the movies’ greatest stars — in the minds of the general public, that is; true movie buffs know her worth. Greta Garbo and Marilyn Monroe, at the height of their careers, were never as popular or as sexy as Clara. But Greta and Marilyn are enshrined in the Temple of Screen Immortals, even to people who know them only by name, while the name of Clara Bow is something out of a quaint, distant, forgotten prehistory, like Nell Gwyn or Minnie Maddern Fiske.

This is unfair. To see Clara Bow at her best — in Mantrap (1926), or in It or Wings (both ’27) — is to see someone who is still as animated and as immediately alluring as she was the day she reported to the set. Everybody who ever worked with Clara spoke of her ever after with a wistful smile. More to the point, the camera loved her as it has loved few other women who ever stood in front of one.

She’s been the victim, perhaps, of the legend that her atrocious Brooklyn accent doomed her when sound came in. Not so. While it’s true that the microphone terrified her at first, she rolled with the punch and gamely soldiered on. In her 11-year career she appeared in 56 features, and 11 of them were talkies. There was nothing wrong with her voice, any more than there was with Jean Harlow’s (the two women’s careers overlapped by a few years). Clara’s sound pictures did reasonably well at the box office, though it’s true, not as well as her silents. But that’s not because Clara was talking now. The simple truth is that her day was passing, while Jean Harlow’s was coming on.

I’ll save any further thoughts for another day. For now, let’s turn to Clara’s Sunday double bill in Columbus.

First came The Saturday Night Kid (1929), based on Love ‘Em and Leave ‘Em, a 1926 play by George Abbott and John V.A. Weaver. The play was filmed silent (also in ’26) under its original title (and screened at Cinevent in 2010), with Evelyn Brent and Louise Brooks playing Mame and Janie Walsh, two sisters who work together at a big department store. Mame is the older, more responsible one, forever mother-henning her hedonistic, troublemaking kid sister Janie. For this talkie remake, Clara played the slightly renamed Mayme and Jean Arthur was Janie (though she was in fact five years older than Clara). Janie is a hell-raiser and borderline sociopath, playing the ponies with the store empoyees’ charity fund, losing it, then blaming Mayme for the embezzlement — and even trying to steal Mayme’s boyfriend (James Hall). Clara wasn’t looking her best (she was, just this once, a trifle overweight and a bit frowzy), but the picture was a hit in 1929 and it still plays well; when Mayme finally got fed up and slapped Janie clear across their bedroom, applause rippled through the Cinevent audience.

First came The Saturday Night Kid (1929), based on Love ‘Em and Leave ‘Em, a 1926 play by George Abbott and John V.A. Weaver. The play was filmed silent (also in ’26) under its original title (and screened at Cinevent in 2010), with Evelyn Brent and Louise Brooks playing Mame and Janie Walsh, two sisters who work together at a big department store. Mame is the older, more responsible one, forever mother-henning her hedonistic, troublemaking kid sister Janie. For this talkie remake, Clara played the slightly renamed Mayme and Jean Arthur was Janie (though she was in fact five years older than Clara). Janie is a hell-raiser and borderline sociopath, playing the ponies with the store empoyees’ charity fund, losing it, then blaming Mayme for the embezzlement — and even trying to steal Mayme’s boyfriend (James Hall). Clara wasn’t looking her best (she was, just this once, a trifle overweight and a bit frowzy), but the picture was a hit in 1929 and it still plays well; when Mayme finally got fed up and slapped Janie clear across their bedroom, applause rippled through the Cinevent audience.

Next, Kid Boots (1926) was one of those oddities, a silent movie based (albeit loosely) on a Broadway musical comedy produced by Florenz Ziegfeld. Ziegfeld’s star Eddie Cantor made his screen debut here, playing a man hired to flirt with a rich man’s gold-digging wife and give the husband grounds for divorce. At a mountain resort, Eddie hits it off with the swimming instructor — but their romance proceeds awkwardly because every time she sees him he’s wooing somebody else. Since Eddie couldn’t resort to song-and-dance, he was teamed with Clara (as the swimming instructor) for box-office insurance. It was a felicitous pairing. The two got along famously; Eddie helped Clara with her comic timing and she helped him learn how to act for the camera, and their rapport and mutual affection still come through on the screen.

After lunch there was a new wrinkle this year. They called it the Audience Choice Picture: Earlier in the year, on the Cinevent Web site, those of us planning to attend were polled as to which of four titles we’d like to see screened in this slot. I can’t remember what the four choices were, nor which one I voted for, but we wound up with The Parson of Panamint (1941), from a story by Peter B. Kyne. Like Kyne’s perennially popular The Three Godfathers, the story was a parable. Charlie Ruggles (in a change-of-pace straight dramatic role) plays the mayor of the rough-and-tumble mining town of Panamint, California. The mayor goes to the big city of San Francisco to hire a preacher for his town’s new church, and that’s where he finds the Rev. Philip Pharo (Phillip Terry) — not in a church, but taking the mayor’s part in a saloon fight. The Rev. Mr. Pharo accepts the job and rides back with the mayor to his new congregation.

After lunch there was a new wrinkle this year. They called it the Audience Choice Picture: Earlier in the year, on the Cinevent Web site, those of us planning to attend were polled as to which of four titles we’d like to see screened in this slot. I can’t remember what the four choices were, nor which one I voted for, but we wound up with The Parson of Panamint (1941), from a story by Peter B. Kyne. Like Kyne’s perennially popular The Three Godfathers, the story was a parable. Charlie Ruggles (in a change-of-pace straight dramatic role) plays the mayor of the rough-and-tumble mining town of Panamint, California. The mayor goes to the big city of San Francisco to hire a preacher for his town’s new church, and that’s where he finds the Rev. Philip Pharo (Phillip Terry) — not in a church, but taking the mayor’s part in a saloon fight. The Rev. Mr. Pharo accepts the job and rides back with the mayor to his new congregation.Day 3

Another regular — and eagerly anticipated — feature of Cinevent is the Saturday morning cartoon program, compiled and curated by animation maven Stewart McKissick. This year the bill included a specimen from each of the major cartoon studios of the 1930s through ’50s — Disney, Warner Bros., MGM, Fleischer, UPA, etc. The clear highlight of the morning was MGM’s Magical Maestro (1952) by the great Tex Avery, in which a spurned vaudeville magician wreaks vengeance by disrupting an operatic recital by “the Great Poochini” (as the poster shows, the cartoon is populated by dogs). It’s a wild and zany ride that anticipates (may even have inspired) Chuck Jones’s Duck Amuck over at Warners the following year, and it’s better seen than described.

Fortunately, that can be arranged. Click here to see the cartoon complete from beginning to end — including a few fleeting (and fairly harmless) seconds of non-p.c. ethnic humor. It’s only six-and-a-half minutes, and worth the side trip. I’ll wait till you get back. (NOTE: The cartoon is on a Romanian-language Web site and is preceded by a commercial for one product or another. Look for a white “X” in the top right corner of the frame or the word “Inchide” [“skip”] in the bottom right; click on either of those and it’ll go directly to the cartoon.)

The cartoon program was followed by Houdini (1953), a purported biopic starring a youthful Tony Curtis and then-wife Janet Leigh as the legendary escapologist and his wife Bess. A big hit in 1953, the picture was a mainstay of Saturday afternoon kiddie matinees when I was going to them — I remember seeing it three or four times — and I’ve always had a soft spot for it. There was, of course, a magician and escape artist (born Erik Weisz) who billed himself as Harry Houdini, and his wife Wilhelmina Beatrice was known as Bess; aside from that, the movie is arrant fiction from first frame to last — but it’s as entertaining as it is made-up. Seeing it in Columbus this year — especially right after a whole slew of cartoons — made me feel seven years old again.

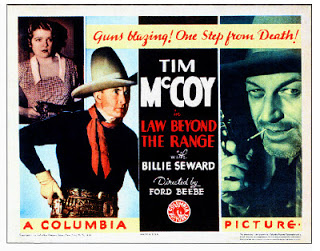

This was followed by Tim McCoy in Law Beyond the Range (1935), an unpretentious and quite entertaining B western from Columbia. Tim McCoy was one of those interesting characters who sort of backed into movies because making movies was fun and he himself was fairly comfortable in front of camera. Born in Saginaw, Michigan, in 1891, he became fascinated with the Wild West as a student in college; he dropped out and resettled in Wyoming, where he became a ranch hand and expert horseman. After serving in World War I (he rose to the rank of colonel and later, in his movie career, was sometimes billed as Col. Tim McCoy), he was appointed adjutant general of the Wyoming National Guard. In that capacity he worked diplomatically and well with Wyoming’s native Arapaho and Shoshone tribes, and in 1922, when Paramount came to Wyoming to film their epic The Covered Wagon, McCoy served as liaison between the company and several hundred Indian extras. That gave him the bug. He resigned his commission and cried “Westward ho!” once again, settling in Hollywood, where he worked steadily through the 1940s, then tapered off into retirement, making his last appearance in Requiem for a Gunfighter in 1965.

This was followed by Tim McCoy in Law Beyond the Range (1935), an unpretentious and quite entertaining B western from Columbia. Tim McCoy was one of those interesting characters who sort of backed into movies because making movies was fun and he himself was fairly comfortable in front of camera. Born in Saginaw, Michigan, in 1891, he became fascinated with the Wild West as a student in college; he dropped out and resettled in Wyoming, where he became a ranch hand and expert horseman. After serving in World War I (he rose to the rank of colonel and later, in his movie career, was sometimes billed as Col. Tim McCoy), he was appointed adjutant general of the Wyoming National Guard. In that capacity he worked diplomatically and well with Wyoming’s native Arapaho and Shoshone tribes, and in 1922, when Paramount came to Wyoming to film their epic The Covered Wagon, McCoy served as liaison between the company and several hundred Indian extras. That gave him the bug. He resigned his commission and cried “Westward ho!” once again, settling in Hollywood, where he worked steadily through the 1940s, then tapered off into retirement, making his last appearance in Requiem for a Gunfighter in 1965. After dinner came of two of the highlights of the whole weekend — both, as it happened, from Universal. First was California Straight Ahead (1937). I here reproduce the title card from the movie’s credits, rather than a poster or lobby card, to make a point: It’s 1937, two years before Stagecoach, and John Wayne is billed above the title. And not in a B western from Monogram or Republic, but in one of six pictures he made at Universal (none of them westerns) before returning to the saddle at Republic. It’s still a B picture, of course; it would take John Ford to promote the Duke out of B’s once and for all. But California Straight Ahead has a better-than-B professional gloss to it; with Universal’s backlot and production infrastructure a few dollars could go a lot farther than they could on some location ranch up in the San Fernando Valley.

After dinner came of two of the highlights of the whole weekend — both, as it happened, from Universal. First was California Straight Ahead (1937). I here reproduce the title card from the movie’s credits, rather than a poster or lobby card, to make a point: It’s 1937, two years before Stagecoach, and John Wayne is billed above the title. And not in a B western from Monogram or Republic, but in one of six pictures he made at Universal (none of them westerns) before returning to the saddle at Republic. It’s still a B picture, of course; it would take John Ford to promote the Duke out of B’s once and for all. But California Straight Ahead has a better-than-B professional gloss to it; with Universal’s backlot and production infrastructure a few dollars could go a lot farther than they could on some location ranch up in the San Fernando Valley.

In his introduction to the screening, Wayne biographer Scott Eyman told us that Wayne regarded his six-picture foray at Universal as a mistake; it had failed to take him out of the “juvenile ghetto” of Saturday afternoon B westerns, and when it was over he found himself back at Square One in Republic horse operas — without his former momentum and unsure when, or if ever, he could work his way out of them. (He couldn’t know, of course, that his big break was just around the corner.) I quote Scott at length on California Straight Ahead and the Duke’s five other Universal B’s: “This is a good movie; they are all good, solid movies. They’re better, frankly, I think, than the Republic westerns he’d been making, because the technicians are a little bit better, the scripts are a little bit better, and the production schedules a little bit longer, and you can get more of where he’s not just riding and roping and slugging people. He actually gets a chance to do a little acting in these movies. And as you’ll see, he’s getting better and better. By 1937, and finishing up this series of pictures, he’s ready. He’s ready for John Ford, he’s ready for the Big Time.”

And then came the deluge, again courtesy of Universal Pictures. The title of this onslaught was Crazy House, and the leading inmates of the loony bin were two slap-happy vaudevillians named Ole Olsen and Chic Johnson. How do you describe these two to someone who’s never seen them? In my last post I called them the Monty Python of the 1940s, but the truth is, Olsen and Johnson made Monty Python look like a Sunday afternoon game of whist between Oscar Wilde and James MacNeill Whistler.

And then came the deluge, again courtesy of Universal Pictures. The title of this onslaught was Crazy House, and the leading inmates of the loony bin were two slap-happy vaudevillians named Ole Olsen and Chic Johnson. How do you describe these two to someone who’s never seen them? In my last post I called them the Monty Python of the 1940s, but the truth is, Olsen and Johnson made Monty Python look like a Sunday afternoon game of whist between Oscar Wilde and James MacNeill Whistler. A regular feature at every Cinevent is a program of Charley Chase shorts. If you don’t recognize the name, it’s worth the effort to familiarize yourself. Unlike some other greats of silent comedy (Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd, Laurel and Hardy), Chase never graduated from shorts to features (though he turned in a delightful supporting performance in Laurel and Hardy’s Sons of the Desert in 1933). Still, his output was prodigious; Cinevent could present a program of five of his shorts (assuming they all survived, which unfortunately they don’t) and go 50 years without repeating one. Cinevent regulars and others familiar with him may skip the next two paragraphs.

A regular feature at every Cinevent is a program of Charley Chase shorts. If you don’t recognize the name, it’s worth the effort to familiarize yourself. Unlike some other greats of silent comedy (Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd, Laurel and Hardy), Chase never graduated from shorts to features (though he turned in a delightful supporting performance in Laurel and Hardy’s Sons of the Desert in 1933). Still, his output was prodigious; Cinevent could present a program of five of his shorts (assuming they all survived, which unfortunately they don’t) and go 50 years without repeating one. Cinevent regulars and others familiar with him may skip the next two paragraphs.

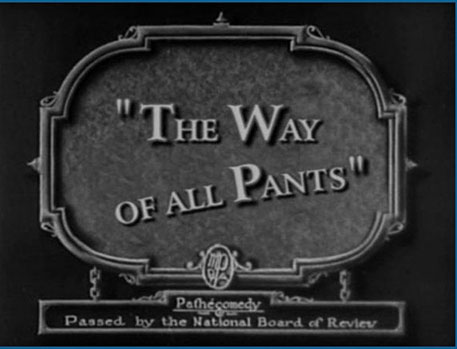

That’s the quick-and-dirty version of Chase’s career, and some day I may post on him in more detail. For now, suffice it to say that Cinevent is doing its share to keep Chase’s name alive (as Richard Roberts aptly put it, he’s not so much neglected as taken for granted) with these regular annual tributes. This year the Cinevent audience got a real scoop: in addition to the shorts Powder and Smoke, Stolen Goods, Too Many Mammas (all 1924), and Looking for Sally (’25), the Chase program included The Way of All Pants (‘27), complete for the first time in a couple of generations. A truncated version of Pants has survived in the Robert Youngson compilation The Further Perils of Laurel and Hardy (’67), but the complete two-reeler was long believed lost. A British release print was recently discovered, with some damage due to age and decomposition; it was digitally restored, then transferred back to 16mm film for screening in Columbus. The whole thing was touch-and-go right down to the wire: the print wasn’t completed until just a few weeks beforehand; it wasn’t even mentioned in the program book because they weren’t sure it would be ready in time to be “re-premiered” at Cinevent.

That’s the quick-and-dirty version of Chase’s career, and some day I may post on him in more detail. For now, suffice it to say that Cinevent is doing its share to keep Chase’s name alive (as Richard Roberts aptly put it, he’s not so much neglected as taken for granted) with these regular annual tributes. This year the Cinevent audience got a real scoop: in addition to the shorts Powder and Smoke, Stolen Goods, Too Many Mammas (all 1924), and Looking for Sally (’25), the Chase program included The Way of All Pants (‘27), complete for the first time in a couple of generations. A truncated version of Pants has survived in the Robert Youngson compilation The Further Perils of Laurel and Hardy (’67), but the complete two-reeler was long believed lost. A British release print was recently discovered, with some damage due to age and decomposition; it was digitally restored, then transferred back to 16mm film for screening in Columbus. The whole thing was touch-and-go right down to the wire: the print wasn’t completed until just a few weeks beforehand; it wasn’t even mentioned in the program book because they weren’t sure it would be ready in time to be “re-premiered” at Cinevent.

The second day of Cinevent began with a departure from custom and a real curiosity: Die Reise nach Tilsit (The Trip to Tilsit), a 1939 German film. That’s the departure; Cinevent has heretofore screened almost exclusively (if not entirely so) English-language movies. The curiosity is that The Trip to Tilsit is based on the same Hermann Sudermann story that inspired F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise (1927): a cheating husband plots to murder his wife and make it look like an accident, but changes his mind when the couple visit the big city and rekindle their love for each other. The compare-and-contrast lends The Trip to Tilsit a fascination it doesn’t have all by itself; it’s well-crafted and well-acted, especially by Kristina Soderbaum (wife of director Veit Harlan) as the wronged wife. But Sunrise is one of the supremely transcendent visual poems of movie history, a movie that, once seen, is never forgotten; The Trip to Tilsit, well-made as it is, is just a mundane Teutonic soap opera. Historian and Cinevent regular Richard M. Roberts dismissed it as “the Nazi Sunrise“, and that just about nails it. (Director Harlan was an ardent Nazi who joined the party in 1933 and prospered during the ’30s turning out propaganda for Josef Goebbels, culminating in the viciously anti-Semitic Jew Suss in 1940.)

One more point of interest about The Trip to Tilsit. Playing the philandering husband (and also good) was a Dutch actor named Hein van der Niet, billed as Frits von Dongen. Unlike his director, van der Niet fled the Nazis at the outbreak of World War II and wound up in Hollywood working as a freelance actor under the name Philip Dorn. He was Hal Wallis’s first choice to play Victor Laszlo in Casablanca — personally, I say it’s a pity he didn’t — but he had already signed for Random Harvest at MGM and the scheduling wouldn’t work. No telling how Dorn’s career might have gone if he had done Casablanca instead of Paul Henreid, but as it was he still managed to rack up a pretty good career — Ziegfeld Girl, Tarzan’s Secret Treasure, Calling Dr. Gillespie, Passage to Marseilles and The Fighting Kentuckian, among others (he was especially fine as Irene Dunne’s husband in I Remember Mama) — before ill-health forced his retirement in 1955. He died in Los Angeles 20 years later, age 73.

After “the Nazi Sunrise” it was back to Hollywood and the English language for Every Night at Eight (1935), a well-above-average musical from Paramount. George Raft and Alice Faye (on loan from 20th Century Fox) were top-billed, but the prime role went to radio singer Frances Langford, in her feature debut. Alice and Frances played two of three pals (the third was Patsy Kelly) seeking and finding radio stardom with bandleader Raft. Raoul Walsh, better known for movies like High Sierra, They Died With Their Boots On and White Heat, directed at a lively pace, and there was a bunch of first-rate songs, two of which are still with us: “I Feel a Song Comin’ On” and “I’m in the Mood for Love”.

After “the Nazi Sunrise” it was back to Hollywood and the English language for Every Night at Eight (1935), a well-above-average musical from Paramount. George Raft and Alice Faye (on loan from 20th Century Fox) were top-billed, but the prime role went to radio singer Frances Langford, in her feature debut. Alice and Frances played two of three pals (the third was Patsy Kelly) seeking and finding radio stardom with bandleader Raft. Raoul Walsh, better known for movies like High Sierra, They Died With Their Boots On and White Heat, directed at a lively pace, and there was a bunch of first-rate songs, two of which are still with us: “I Feel a Song Comin’ On” and “I’m in the Mood for Love”.

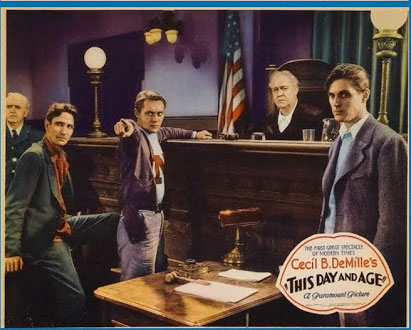

…And then came Cecil B. DeMille’s This Day and Age (1933). Talk about a curiosity! Richard Cromwell plays the leader of a group of high school students who get appointed to ceremonial positions in city government — judge, chief of police, district attorney, etc. — as a way to give them an on-the-job view of how the grownups run things. When a friend of theirs is murdered by a local gangster (Charles Bickford) who gets off scot-free thanks to an oily high-priced attorney, the kids take over the government for real, kidnapping the gangster and torturing a confession out of him (“We haven’t got time for rules of evidence!”), after which the adults see the error of their ways. The trauma of the Great Depression spawned more than one movie like this — check out a little oddity called Gabriel Over the White House (’33) sometime — movies where audiences could vent their frustrtion with “the System” by vicariously experiencing things they’d never get away with (or seriously contemplate) in real life.

…And then came Cecil B. DeMille’s This Day and Age (1933). Talk about a curiosity! Richard Cromwell plays the leader of a group of high school students who get appointed to ceremonial positions in city government — judge, chief of police, district attorney, etc. — as a way to give them an on-the-job view of how the grownups run things. When a friend of theirs is murdered by a local gangster (Charles Bickford) who gets off scot-free thanks to an oily high-priced attorney, the kids take over the government for real, kidnapping the gangster and torturing a confession out of him (“We haven’t got time for rules of evidence!”), after which the adults see the error of their ways. The trauma of the Great Depression spawned more than one movie like this — check out a little oddity called Gabriel Over the White House (’33) sometime — movies where audiences could vent their frustrtion with “the System” by vicariously experiencing things they’d never get away with (or seriously contemplate) in real life.It’s been way too long — over a year-and-a-half — since I posted anything new here at Cinedrome. I want to apologize for that. I won’t overstate the concerns and conditions that led me to suspend blogging. Nor will I exaggerate the number of posts I began and never got around to finishing. But there have been some of both.

Be that as it may, I’ve had my necessary vacation and I feel rested, refreshed, and ready to soldier on. So with that, I file the following report on the 48th Annual Cinevent Classic Film Convention in Columbus, Ohio.

This was Cinevent’s second year in its new home, Columbus’s Renaissance Downtown Hotel. The convention’s previous, longtime venue, which had changed hands and names several times over the decades, closed suddenly — and permanently — in February 2015, only three months before that year’s Cinevent. Which, with an undertaking of this scale, qualifies as “at the last minute”. The Cinevent Committee had to scramble madly to find another venue, and by the grace of a merciful Providence the Renaissance was available. Better yet, the new place proved to be a step above the old one. Did I say a step? Actually, the new place is about three flights above the old one: superior accommodations, a better screening room with more comfortable chairs, a bigger dealers’ room, everything centrally located on one floor — and the hotel itself centrally located in a much better neighborhood, one block from the Ohio State House, with plenty of good restaurants nearby.

The Renaissance is now, as I said, Cinevent’s new home — but it wasn’t available for Memorial Day Weekend this year, so the get-together was delayed a week to June 2 – 5. Next year (the contract has already been signed) they’ll be going back to Memorial Day.

The first day featured a screening of King Vidor’s classic slice of life The Crowd (1928), one of the greatest pictures of the silent era — and probably one of the top 40 or 50 of all time. The Crowd is readily available on video and pops up regularly on Turner Classic Movies. Much harder to find — incredibly rare, as a matter of fact — was a program of all-but-lost comedy shorts from Fox Film Corp. For me, the highlights of the first day were Melody Cruise, a 1933 comedy starring Charlie Ruggles and Phil Harris (in his movie debut, 30-plus years before voicing Baloo the Bear in Walt Disney’s The Jungle Book); and The House of Rothschild (1934), from Darryl F. Zanuck’s fledgling 20th Century Pictures.

And by an astonishing coincidence, those happen to be the two pictures at this year’s Cinevent for which I supplied the program notes. And here they are:

Melody Cruise (1933) With a title like Melody Cruise and a leading man like Phil Harris, you can be forgiven if you expect this picture to be one uninterrupted songfest. Well, it’s not exactly, so you’ll be wise to dial those expectations back a bit so you can join in the fun. It’s not really a musical — a “comedy with songs” would be a better term. But director Mark Sandrich — who was finally, after six years directing shorts for various studios, beginning to graduate once and for all to features — assembles the picture with an intuitive sense of musical rhythm that would come to full bloom in his partnership with Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers.

Melody Cruise concerns a trip by sea from New York through the Panama Canal to Los Angeles undertaken by two men, both well-to-do and each with an eye for the ladies: Pete Wells (Charlie Ruggles), a married man best described as a “male flirt”; and Alan Chandler (Phil Harris), a confirmed bachelor who loves to romance the fair sex but is (in the words of one of the movie’s semi-songs) “not the marrying kind.” In order to avoid any possibility of being waylaid into matrimony, Alan dispatches a letter to Pete’s wife in California “to be opened only in the event of my marriage” and detailing all of Pete’s marital indiscretions while husband and wife were on separate coasts; this, Alan figures, will give Pete a vested interest in scotching any shipboard romances that his bachelor pal may fall into.

Ah, but the best-laid plans…No sooner does the ship leave the pier than Alan meets winsome Laurie Marlowe (Helen Mack), and this bachelor suddenly finds himself feeling much less confirmed. Throw in an old flame of Alan’s who is also aboard (Greta Nissen), and a couple of randy party girls from Pete’s bon voyage celebration who linger in his stateroom after the vessel sails (June Brewster, Shirley Chambers), and the ingredients of an old-fashioned farce of misunderstandings and mistaken identity are in place, and the voyage promises to be a busy one for all concered.

The plot of this RKO pre-Code may be tissue-thin, but the execution gives it a gloss of frivolous fun. We can detect the influence of the previous year’s Love Me Tonight (from over at Paramount) right off the bat, as passengers in a shipping office negotiate for their respective cruises in a sort of recitative of rhyming dialogue, while the underlying music suggests a melody for their words that would become a song if anyone wanted to sing (the songs are credited to Val Burton and Will Jason). It happens again later as the ship sets sail, with the activities of the crew carefully choreographed to Max Steiner’s music, and later still as the ladies aboard (look sharp and you’ll catch a glimpse of 16-year-old Betty Grable) gossip about Alan Chandler in “He’s Not the Marrying Kind”. And in the picture’s one full-fledged song, sung by Phil Harris to Helen Mack as their ship waits its turn at the moonlit Panama Canal, both the title (“Isn’t It a Night for Love?”) and the staging are redolent of “Isn’t It Romantic?” from Love Me Tonight.

Making his screen debut here (if you don’t count an uncredited background bit as a nightclub drummer in 1929’s Why Be Good? with Colleen Moore), Phil Harris is younger, sleeker and smoother than the big loveable galoot we all remember from Jack Benny’s radio program and movies like The Wild Blue Yonder (1948) and The High and the Mighty (1954). Later on in 1933, he and director Sandrich would collaborate on the short So This Is Harris!, which would go on to win an Oscar for best comedy short subject.

Melody Cruise got an indulgent recpetion from the critics. Variety’s “Rush” found it “just a well-rehearsed trifle, padded out unmercifully with incidentals, atmosphere and other embroideries”, but allowed that “photography and technical production are better than first class, becoming notable for excellence at many points” — an apparent nod to the many whimsical screen-wipes Sandrich and conematographer Bert Glennon use to transition from scene ot scene. Likewise Mordaunt Hall in the New York Times, who called it “an adroit mixture of nonsense and music which makes for an excellent Summer show…It is, however, not the singing or the clowning that makes this a smart piece of work, but the imaginative direction of Mark Sandrich, who is alert in seizing any opportunity for cinematic stunts. From the viewpoint of direction this production is quite an achievement, for there are moments when it has a foreign aspect and there is some extraordinarily clever photography.”

The House of Rothschild (1934) At the beginning of 1933, Darryl F. Zanuck was head of production at Warner Bros., the man behind The Jazz Singer, Little Caesar, The Public Enemy, 42nd Street, and other seminal pictures of Warners’ pre-Code era. On April 15, Zanuck abruptly resigned. As might be expected — especially with Warner Bros. — it was due to a dispute over money. For once, though, it wasn’t Zanuck’s money that was being disputed. Zanuck had reluctantly agreed to be the bearer of the bad news when the brothers imposed temporary studio-wide pay cuts in the wake of FDR’s bank holiday in March ’33. When studio chief Jack Warner decided to extend the cuts beyond the agreed-upon end date, Zanuck felt that he (Warner) had broken his (Zanuck’s) word to the employees. Harsh words flew, and Zanuck took a walk.

The House of Rothschild (1934) At the beginning of 1933, Darryl F. Zanuck was head of production at Warner Bros., the man behind The Jazz Singer, Little Caesar, The Public Enemy, 42nd Street, and other seminal pictures of Warners’ pre-Code era. On April 15, Zanuck abruptly resigned. As might be expected — especially with Warner Bros. — it was due to a dispute over money. For once, though, it wasn’t Zanuck’s money that was being disputed. Zanuck had reluctantly agreed to be the bearer of the bad news when the brothers imposed temporary studio-wide pay cuts in the wake of FDR’s bank holiday in March ’33. When studio chief Jack Warner decided to extend the cuts beyond the agreed-upon end date, Zanuck felt that he (Warner) had broken his (Zanuck’s) word to the employees. Harsh words flew, and Zanuck took a walk.Over the weekend of Sept. 27 – 28, I had an opportunity to revisit two of my favorite David O. Selznick pictures. On Sunday the 28th it was the Turner Classic Movies two-day-only theatrical reissue of Gone With the Wind. I’m sure many of my Cinedrome readers (among others) availed themselves of that one — at least, if the size of the audience I saw it with is any indication.

On Saturday the 27th, however, the reunion was more private: a family-and-friends home screening of 1938’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. I’ll be spending most of this post talking about that one, because…well, of all the terms you might use to describe Gone With the Wind, “neglected classic” is certainly not one of them.

Some years ago, my friend John McElwee over at Greenbriar Picture Shows posted on Tom Sawyer here and here. “Does anyone else share my longstanding affection for this show?” John asked rhetorically. In the comments I replied, “Good heavens, doesn’t everyone share it?”

Well, apparently not; in David O. Selznick’s Hollywood Ron Haver dismissed it as “basically old fashioned and slightly dull”, and it has little of the latter-day respect accorded other Selznick pictures such as Nothing Sacred or the original A Star Is Born. Still, John and I aren’t entirely alone; Leonard Maltin gives Tom Sawyer three-and-a-half stars, and I have anecdotal evidence aplenty of the picture’s enduring ability to please any crowd.

In fact, I’m going to go out on a limb and assert that Selznick’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer is just about the best movie ever made from any story by Mark Twain. (For the record, I’d give a close-second place to Warner Bros.’ 1937 The Prince and the Pauper, and an equally close third to 1960’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn with Eddie Hodges and Archie Moore.)

But back to Tom Sawyer. Selznick originally hoped to shoot the picture in Technicolor, but there were no Tech cameras available. So instead, he began shooting in March 1937 in black and white, with H.C. Potter directing. Shooting proceeded in fits and starts until July, when Technicolor cameras unexpectedly became free; Selznick closed down production, had the location sets all repainted, replaced some cast members (Beulah Bondi was out as Aunt Polly, May Robson in), and brought Norman Taurog in to direct (Potter having walked off, exasperated with Selznick’s incessant kibitzing). The final negative cost, John McElwee tells us, was $1.2 million — some sources say as high as $1.5 million, but I trust John on things like this. Anyhow, whatever the cost, it was astronomical for the time, especially for a picture with no battle scenes, no production numbers, and no scenes using more than maybe 50 or 60 extras. (As a very broad rule of thumb, multiply any figures from this era by about 100 to get an idea of the cost in today’s dollars.) The bottom line: despite some glowing reviews and high hopes, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer broke nowhere near even, losing some $302,000 — probably more than the picture would have cost if it had been produced anywhere but at Selznick International.

The picture got a handful of reissues over the years, both before and after Selznick sold it off (along with the rest of his library) during his cash-strapped 1940s — the poster above is from one of those reissues — and that’s how I first saw it in 1958; my father, with fond memories of having seen it back in ’38, took the whole family to see it at the Vogue Theatre in Pittsburg, Calif. My brother was only four years old at the time, and I still remember his reaction: He sat down with a bag of M&Ms from the snack bar, took one out ready to pop it in his mouth, looked up at the screen, and was instantly hooked. As the movie ended and the lights came up, he was sitting there with that first M&M still between the thumb and forefinger of his left hand (and no, it hadn’t melted).

Today that four-year-old has 13 grandchildren of his own, and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (Mark Twain’s original book) has been working its way through the family. My brother read it, and my sister-in-law, and their daughter has been reading it to her three kids. This prompted a groundswell of requests for a family screening of my 16mm print, which I last screened some six or eight years ago, before many of the kids were born. So I scheduled the screening for September 27, and got out my print to see what sort of shape it was in.

And here I have to discuss the color in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (Selznick’s movie) — in general, and in my print in particular.

The second (and, so far, last) time I saw The Adventures of Tom Sawyer in a theater was at the Stanford Theatre in Palo Alto, Calif. in the late 1980s. Now the Stanford is operated by the Stanford Theatre Foundation, which is headed by David W. Packard (son of the founder of Hewlett-Packard) and has contributed millions in cash and resources to the cause of film preservation. Consequently, the Stanford is on excellent terms with film archives all over the country. Any time a picture plays the Stanford, you can rest assured that you’ll be seeing the very best available print.

So it didn’t bode well that the print I saw that night in 1989 was a slightly red-shifted Eastman print. Oh dear, I thought. Could it be that The Adventures of Tom Sawyer was one of those pictures that hasn’t survived in Technicolor at all? (No, as it turned out. But I’m getting ahead of myself.)

My own 16mm print, when I acquired it about ten years ago, was yet another Eastman print, and the color was distinctly faded. Also, over the years and reissues the running time had been whittled down from 93 to 77 minutes; my print ran 79. When I scheduled the family screening for last month, I hadn’t looked at it in years, so I cranked up the projector to see what condition it was in. Bad news — the color was pretty much shot, and in some scenes even the image was going fast. This print would do, but only in a terrible pinch — so I decided to shop around and see what else I could find.

To make a long story short — if it’s not already too late for that — I found two DVDs. One was a Region 2 British DVD, the other a transfer from South Korea (that one defaulted to Korean subtitles, but through the miracle of DVD I could turn those off). Why this quintessentially American story is available on DVD in Great Britain and South Korea, of all places, but not in the United States is one of those vagaries of video that defy explanation, but there it is. (In any case, it’s a powerful argument for owning a region-free player.)

Either one of these DVDs was a huge improvement over my 16mm print, but the difference between the discs themselves was like night and day. The South Korean disc, in fact, might almost have been made from the print I saw in Palo Alto: it had the same red-shifted, high contrast image. The British DVD, on the other hand, must surely have been transferred from the restoration Disney made when they gained control of the picture in the early 1990s (see Part 2 of John McElwee’s post for details of that restoration). So to answer the question I asked myself that night in Palo Alto: No, the Technicolor Tom Sawyer is not lost; it still exists — if only on DVD. Here are some frame-caps comparing the two transfers, South Korea on the left and UK on the right:

|

|

First, here’s Tom (Tommy Kelly) and Becky Thatcher’s (Ann Gillis) first after-school “date”. Notice the increased detail and texture, especially in the hill behind them and the creek under their feet, and the purer fleshtones. Notice, too, in all these frames that the Korean disc crops the image along all four edges.

Below, Tom and Joe Harper (Mickey Rentschler, left) play pirate on their island in the Mississippi, unaware that the folks back home believe they’ve been drowned. As in that frame above with Tom and Becky, the grass is a whole lot greener (and the sky less purple) in true Technicolor.

|

|

Below, Becky and Tom on the way to the school outing where they’ll become lost in the cave (superbly designed by William Cameron Menzies and built on a soundstage at the Selznick studios). This shot is a particularly dramatic illustration of the difference between the two discs, both in the quality of the color and the size of the image, as is…

|

|

|

|

As you can no doubt gather from those frame comparisons, the British DVD was the way to go, so I put the 16mm projector back in the closet and got out my Epson Powerlite 6100. That old 16mm print of mine I junked; it had long outlived its usefulness. The night of the 27th my family and friends were treated to The Adventures of Tom Sawyer looking better than it has in years; for myself, I don’t know if I’ve ever seen it looking as good as it does on that Region 2 DVD from the United Kingdom. If you’re in the market, accept no substitutes. There are a number of Hollywood classics that are available only in Region 2 DVDs, but for my money, this disc alone justifies the expense of buying a region-free player. (Alternatively, Region 2 DVDs will play on most computers.)

Tom Sawyer, like most of Selznick’s literary adaptations from Little Women to Gone With the Wind, is a perfect illustration of his dictum that it’s less important to film an entire novel than to give the impression that you’ve done so. Mark Twain’s book is loosely constructed and episodic, almost a collection of short stories rather than a unified novel. John V.A. Weaver’s script picks and chooses episodes both for how well they express the spirit of Twain and how they form a solid dramatic arc, building to Tom’s climactic showdown in the cave with Injun Joe (Victor Jory) and his struggle up the rocks to the light and safety (two moments that aren’t in Twain’s book, but which fit neatly into the movie).

The casting and performances are spot-on right down the line. Beulah Bondi was closer to the physical description of Aunt Polly in Twain, but it’s hard to imagine her improving on what May Robson does with the role. Robson perfectly captures the stern-yet-tender heart of Aunt Polly, a remarkable tightrope-walk for an actress to pull off. (By the way, here’s a Fun Fact: Do you know what distinction May Robson, who was nominated for best actress for 1933’s Lady for a Day, has among Academy Award nominees? She’s the only one who was born before the American Civil War, on April 19, 1858. Obviously, that record will stand forever.)

Right smack in the middle of all these perfectly cast veterans — Walter Brennan, Victor Jory, Donald Meek, Olin Howland, Victor Kilian, Frank McGlynn Sr. — there’s one of those little miracles that come along once in a great while: 12-year-old Tommy Kelly as Tom. The son of an unemployed Bronx firefighter, he had never acted before — and truth to tell, in time his acting skills would prove to be extremely limited. But that hardly matters here; he simply is Tom Sawyer — it’s as simple as that. Despite his inexperience, he is center-screen in almost every scene and carries the picture with natural ease. It’s one of those incredibly rare moments when exactly the right person for a role came along, seemingly out of nowhere, at exactly the right time in his life to play it. I’m pleased to report that at this writing, Tommy Kelly is still with us at 89, as are Ann Gillis (Becky Thatcher, now 87) and Cora Sue Collins (Amy Lawrence, also 87). (UPDATE 2/13/19: Tommy Kelly passed away on Jan. 26, 2016, age 90, and Ann Gillis, also 90, on Jan. 31, 2018. Cora Sue Collins will turn 92 on April 19; continued long life to her.)

So how did my screening go over? Like gangbusters, as I knew it would because it always has. None of the kids had ever seen it, and it was a revelation to all of them. I know that in years to come they’ll cherish the movie as a fond childhood memory — as their grandfather and I do, and as our father did before us, and all those grade-schoolers in my uncle and aunt’s classrooms over the years. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer is a guaranteed crowd-pleaser that never seems to age, thanks to Technicolor (now brilliantly restored) and a quaint, old-fashioned style that meshes perfectly with the 19th century nostalgia that infused Mark Twain’s book in the first place.

Then on the next day, Sunday the 28th, it was Gone With the Wind, which I hadn’t seen in a theater since its 50th anniversary reissue in 1989.

The day may come when I have something to say about Gone With the Wind that hasn’t already been said far better by somebody else. But this is not that day. Instead, I’ll just take this opportunity to mention a new book on the subject, and here it is: The Making of Gone With the Wind by Steve Wilson.

Now I will confess that when I heard of this book, the first thing I thought was, “Oh great, just what we need, another book about the making of Gone With the Wind!” And I wasn’t particularly impressed with the book’s cover, with its monochrome image washed in thin blue and green of Vivien Leigh peeking out through the “O” in “GONE” while she grabs a quick cigarette between takes on the set — I mean, was there ever a book cover that conveyed less of a sense of the movie it’s supposed to be about?

So much for gripes and quibbles. I was wrong. No matter how many books on Gone With the Wind you’ve read or thumbed through, this one eclipses them all. It’s actually the companion volume to an exhibition at the Harry Ransom Center, an archive, library and museum complex on the campus of the University of Texas at Austin. The exhibition is running now through January 4, 2015, and it draws from the Center’s massive David O. Selznick archive consisting of 5,000 boxes of documents and photographs and millions of feet of film. Steve Wilson, the book’s author, is curator of the Center’s film collection, and the book takes us step by step through the three-and-a-half years from the day Selznick bought the rights to Margaret Mitchell’s novel to the night the picture swept the 1939 Academy Awards. We see everything from the nationwide talent-search-cum-publicity-tour through shooting (presented chronologically as it was shot), editing, previews, everything. And all of it is illustrated with newspaper clippings, letters, telexes, telegrams, memos, call sheets, concept paintings, makeup and costume tests, notes, set photos, matte paintings, sheet music, maps — you name it, all of them reproduced in their original colors (or lack of them) on high-quality glossy paper.

I thought of scanning a sampling of some of the illustrations and posting them here, but that way lies madness — once I started I’d never be able to stop. Instead, just check out the link to the Harry Ransom Center above, or this link to the Center’s Web exhibit on the movie. That’ll show you more than I could ever post here. After that, just see if this isn’t a book you have to have. At the very least, it’s easier and less expensive than trying to squeeze in a trip to Austin between now and January 4.