“Anyone four years old,” Shirley Temple Black wrote, “absorbs experience like a blotter.” Anyhow, she certainly did, and her experience with the Baby Burlesks gave her plenty to soak up. She learned that making movies was business, and wasting time was wasting money — and if you wasted too much of either, you wouldn’t get any more of it. Se learned about hitting chalk marks on the floor to be properly lit. Even better than that, she found that her face was particularly sensitive to the warmth from the overhead lighting instruments, which made her good at what actors call “finding your light”; she could feel the difference between the light hitting her forehead, her cheek or her chin.

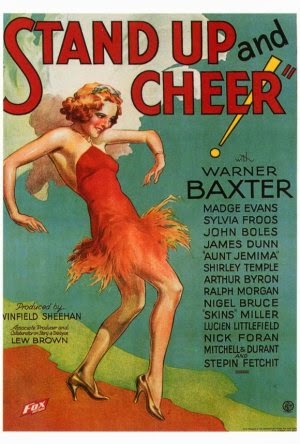

Something else that she found she could do didn’t surface until she made Stand Up and Cheer!: filming to playback. On the Baby Burlesks there hadn’t been time or money for fripperies like pre-recording; when Shirley sang “She’s Only a Bird in a Gilded Cage” in Glad Rags to Riches or “We Just Couldn’t Say Goodbye” in Kid in Hollywood, she performed live on the set to a simple piano, with other instruments to be dubbed in later (even that was an extravagance for penny-pinching Educational). This idea of recording the song first, then mouthing the words later for the camera was entirely new to her. As even the most experienced actors have learned to their dismay, it’s not simply a matter of synchronizing lip movements; your posture, your breathing, the angle of your head, even your facial expressions can all influence the sound your voice makes when you’re singing. If you don’t replicate them precisely, audiences tend to notice the difference, even if they can’t quite put their finger on what’s wrong. Getting it right called for the application of another actorly phrase, “sense memory”. Shirley found that it came easily to her. “Mimicry is not an unusual talent in a child,” she wrote, “and I had no appreciation for what a nasty problem such synchronization presents for many actors.”

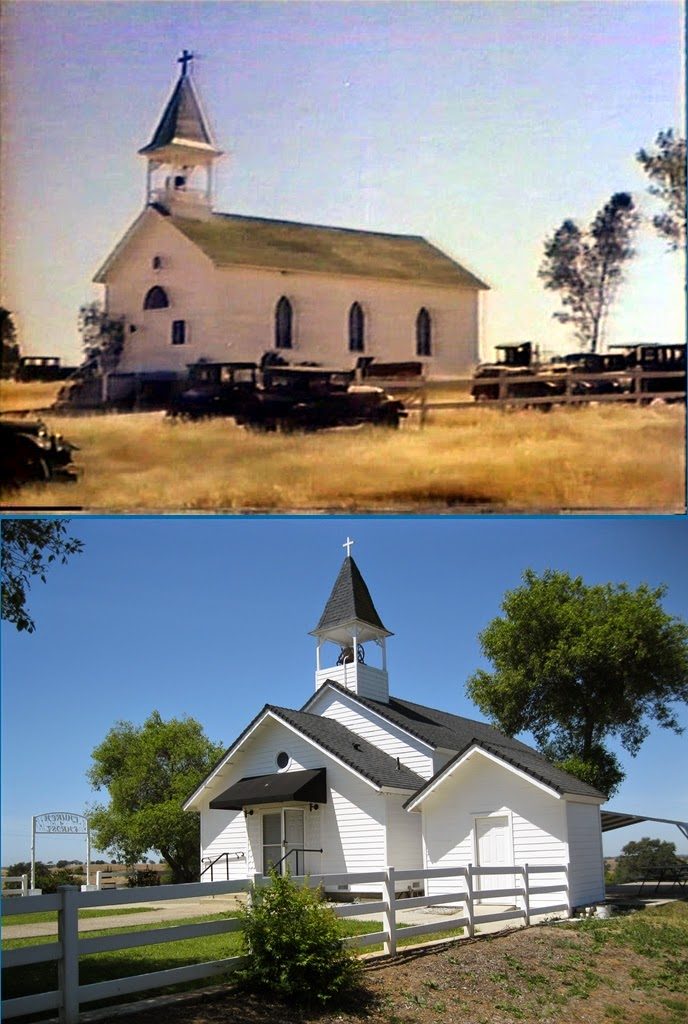

There were many such lessons that went into The Education of Shirley Temple. Henry Hathaway told a story of directing her in To the Last Man, a 1933 western from a Zane Grey novel about an age-old blood feud between two Kentucky clans that continues as both families relocate to the Nevada frontier. Shirley played an uncredited bit (one of her loan-outs from Jack Hays) as a third-generation child of one of the families. (She’s shown here with Muriel Kirkland, left, as her aunt and Gail Patrick as her mother.)

The script called for her to be conducting a play tea party in the yard outside her family’s ranch house when a member of the enemy clan shoots the head off her doll, hoping to prod her father, uncles and grandfather into a showdown.

As the camera rolled, she was to offer a cup of tea to a small pony standing by her table. But the pony became inordinately interested in the sugar bowl on the table and stuck his snout into it. Ad libbing with the moment, Shirley snapped “Get away! Get away!” and slapped the pony’s nose. The scene escalated into a shoving match, with Shirley pushing at the pony and kicking at his fetlocks. As Hathaway looked on in horror (“Oh Jeez, I was scared to death.”), the pony turned his back and kicked viciously at the girl with his hind legs, missing her head by inches. She stood her ground and glared at him: “You ever do that to me again, I’ll kick you!”

Hathaway had seen enough — too much, really. “Cut!” He went up to Shirley. “Didn’t that scare you?”

“Yes,” she said.

“Well, you didn’t stop.”

“Oh, I wouldn’t dare stop.”

Even at the age of five, Shirley already knew two things: (1) animals can’t be counted on to follow the script, and you have to be ready to deal with what they actually do; and (2) no matter what happens, only the director gets to call “Cut!” (By the way, the pony’s kick did not remain in the picture; it would have detracted too much from the “murder” of the doll, the dramatic point of the scene.)

Shirley’s new contract with Fox was exclusive, but in the immediate aftermath of shooting “Baby, Take a Bow” for Stand Up and Cheer! all the studio found for her to do was a less-than-worthless bit in a Janet Gaynor/Charles Farrell romance called Change of Heart. Eight seconds on screen — with her back to the camera, yet! — and not a syllable of dialogue; it was worse than the bits Jack Hays used to send her on. Mother Gertrude set out to drum up some work — if some other studio wanted her daughter, surely a loan could be worked out — and she had just the picture in mind, over at Paramount. It was one for which Shirley had already auditioned and been dismissed out of hand. (“They took one look, watched me dance, and rejected me without a smile.”)

Little Miss Marker

(released June 1, 1934)

Somehow, this time Gertrude was able to wangle an interview with the movie’s director, Alexander Hall. In

Child Star Shirley doesn’t know how Mother did it; I wouldn’t be surprised if word of Shirley’s song-and-dance with James Dunn was already circulating on the Hollywood grapevine. In any event, Shirley auditioned for Hall personally.

The director showed Shirley to a chair and sat facing her. “Say, ‘Aw, nuts.'”

“Aw, nuts!”

“Scram!”

“Scram!”

Hall stood up. “Okay.”

“Okay!”

“No, kid! Stop! We’re finished.” It was as simple as that; Shirley had the part. Paramount offered Fox $1,000 a week for Shirley’s services (a huge profit over the $175 in her Fox contract), and on March 1, 1934 Shirley reported for her first costume fittings for Little Miss Marker.

William R. Lipman, Sam Hellman and Gladys Lehman’s script was adapted from a story by Damon Runyon about a sourpuss bookie named Sorrowful who grudgingly accepts a bettor’s small daughter as a sort of “hostage” for a two-dollar bet on a horse race. The father promises to get the money and be right back, but he never comes back. Sorrowful finds himself saddled with the little girl, whose sunny sweetness gradually thaws his heart, brightens his outlook and loosens his airtight purse strings. Everyone notices the change the tot makes in Sorrowful, and they warm to little “Marky” themselves.

Damon Runyon died in 1946, but his name has stayed current in American culture thanks to the Broadway musical Guys and Dolls (its title taken from one of his story anthologies, its plot from two of his tales). But Guys and Dolls has also skewed the popular image of his stories and what it means to be “Runyonesque”. The musical is set in a rollicking fantasy land of cute underworld denizens — grifters, mugs, oafs and dames, colorful and essentially harmless. In Runyon’s stories there is humor, to be sure, but it’s not rollicking; it’s more often sardonic, even mordant, and the atmosphere of the stories, despite the picturesque speech, is hardly fantasy. The world of Runyon’s nameless narrator is gritty and down to earth, lit by bare bulbs in cheap hotel rooms and the gaudy glare of street neon; we can almost smell the cheap cigars and stale perfume. Things may work out — for the time being — for the characters, but it’s usually thanks to ironic accidents, not a benign universe. There’s often an undercurrent of menace beneath the whimsy, and bad things do happen.

And so it is in “Little Miss Marker”. One snowy night Marky wakes to find her nursemaid asleep and Sorrowful gone. Running outside barefoot in her nightgown, she tracks him to the Hot Box nightclub and runs into his arms just as a killer named Milk Ear Willie is about to settle an old grudge by plugging Sorrowful. Willie changes his mind, so Marky has saved Sorrowful’s life — but at the cost of her own. She contracts pneumonia and dies in hospital, despite the efforts of Sorrowful and his associates (even Milk Ear Willie chips in, kidnapping a famous child specialist to attend Marky’s bedside). Minutes after Marky’s death her father turns up, having suffered from amnesia since the day he left his little girl with the bookmaker. He has read about Marky in the newspapers and has finally come to take her home. “I suppose I owe you something?” he asks Sorrowful. Yes, says the bookie, you owe me two bucks. “I will trouble you to send it to me at once, so I can wipe you off my books.” He is once again the old Sorrowful, with the same “sad, mean-looking kisser” he had before — “and furthermore,” says the narrator, “it is never again anything else.”

The movie keeps Runyon’s hospital climax — Marky is there with life-threatening injuries from falling from a horse, not pneumonia — but softens the ending: Marky lives, and Sorrowful’s reformation is allowed to stick. (The writers also gave Sorrowful a surname, Jones, which is not in the story but has stayed with him through two remakes.) Otherwise, it’s faithful to the spirit of Runyon’s story — basically a drama with small comic flourishes — with a suitable mix of seediness and vulgar glamour. Surely, Runyon was pleased.

Little Miss Marker contains one of the most unusual movie pairings of the 1930s: Shirley Temple and Adolphe Menjou. The usually dapper, immaculately tailored Menjou (he was voted Best Dressed Man in America nine times) was, at first glance, an odd choice not only to team with a child but to portray the rumpled, unkempt Sorrowful Jones. But it works; Shirley’s Marky brings out the debonair sport in Menjou’s Sorrowful, the one we knew was there all the time, by inspiring him to move to a more suitable apartment and upgrade his wardrobe. (Curiously enough, Menjou would play a similarly disheveled grump, and have a similar rapport with kids, in his last picture, Disney’s Pollyanna in 1960 — this time with two child stars, Hayley Mills and Kevin Corcoran.)

Shirley says in Child Star that Menjou once offered to play hide-and-seek with her, but otherwise tended to keep his distance (“off-camera he treated me with the reticence adults commonly reserve for children”). But when the camera’s rolling the two have a remarkable chemistry. It’s there when Marky and Sorrowful first meet, as she stands beside her father on the divider railing in Sorrowful’s shabby office. Sorrowful orders Marky “down offa there”, but she teases him: “Look, Daddy, he’s running away! Is he afraid?…You’re afraid of my daddy! Or you’re afraid of me. You’re afraid of something…” There follows a remarkable moment when Sorrowful picks Marky up, supposedly to get her off the railing, but holds her for a short while, her hands resting on his shoulders, while their eyes meet. Then he sets her down and growls to his henchman Regret (Lynn Overman), “Take his marker…A little doll like that’s worth twenty bucks. Any way you look at it.” (“Yeah,” Regret grumbles, “she oughta melt down for that much.”)

The chemistry is there, too, in a charming scene where Sorrowful and Marky talk about God, and he grudgingly agrees to teach her to say her prayers: “All right, get outta bed. I’ll show you how to pray. Sort of. But don’t you tell anybody, see?” The topper to the scene is the look on Sorrowful’s face when he hears why she wanted to learn: “And please, God, buy Sir Sorry a new suit of clothes.” In the very next scene, Sorrowful the sartorial butterfly has hatched out of his rumpled cocoon. (“Sir Sorry the Sad Knight” is the name Marky gives Sorrowful; she names all his cronies according to the stories she’s heard about King Arthur.)

Marky’s “Lady Guinevere” is Bangles Carson (Dorothy Dell), nightclub singer and kept doll of Big Steve Halloway (Charles Bickford). Bickford, of course, was in the early stages of a long and distinguished career. Dell might have been, too; she was only 19 when she made Little Miss Marker, her second picture, with a husky contralto voice and a wise way with a good line. She too had a strong rapport with Shirley, only this time it extended to off-camera, where she was as much a big sister to her as Bangles is to Marky. Dorothy Dell might have become Paramount’s answer to Alice Faye, Joan Blondell or Jean Harlow. Alas, when this scene of Bangles singing Marky to sleep was shot, Dell had only three months to live. Early in the morning of June 8, 1934, she was returning from a party in Altadena with a friend, Dr. Carl Wagner. On a deceptively sharp curve on Lincoln Avenue in Pasadena, Wagner lost control. The car hit a rock, then, flipping end over end, a light pole and a palm tree. Dorothy was killed instantly, crushed in the mangled wreck. Wagner was thrown clear but died six hours later without regaining consciousness. Shirley was back at Paramount then, making another loan-out (Now and Forever); the studio staff kept the news from her as long as they could.

Some of Shirley and Dorothy’s chemistry is on display in this scene of the two singing one of Bangles’s songs, “Laugh, You Son of a Gun” (by Leo Robin and Ralph Rainger). I post it here not only for Shirley, but for Dorothy; she deserves to be remembered. (UPDATE 9/1/14: Alas, the video clip from Little Miss Marker that was originally embedded here has now gone dead. Here’s a soundtrack-only clip of the song, as it was recorded live on the set during filming; hopefully a full clip will become available someday):

Little Miss Marker

Little Miss Marker fleshed out and in many ways improved Runyon’s original story. The amnesiac-father angle was always a bit of a credulity stretch; in the movie he becomes a suicide — driven off the end of his rope when the bet he placed with Sorrowful turns out a loser. This heightens Sorrowful’s sense of obligation to Marky: the race was rigged and he knew it when he took the man’s bet. It also links Marky to that losing horse, the ironically named Dream Prince. When Big Steve, Dream Prince’s owner, is suspended over suspicions about that fixed race, Steve and Sorrowful set Marky up as Dream Prince’s dummy owner so the horse can continue to run. Marky’s affection for “the Charger” (another one of her fanciful King Arthur names) draws her, Sorrowful and Bangles closer together, and leads to a crisis when Big Steve gets wind of shenanigans behind his back.

Little Miss Marker was a smash hit. With it Shirley Temple truly arrived, and it remains one of her best pictures with one of her best performances. It proved that her show-stopper in Stand Up and Cheer! was no fluke, that she could handle the central role in a major feature and hold her own with a castful of seasoned professionals. Just look at her billing in the picture’s opening credits: her name alone, before the title and just as big — bigger in fact than Menjou, Bickford, Runyon, even director Alexander Hall. Runyon’s story would be filmed again over the years, going from good (Sorrowful Jones [1949] with Bob Hope) to bad (40 Pounds of Trouble [’62] with Tony Curtis) to awful (Little Miss Marker [’80] with Walter Matthau). In every single one, the little girl playing Marky made absolutely no impression whatever. Can you even name them? (If you said Mary Jane Saunders, Claire Wilcox and Sara Stimson, move to the head of the Trivia Seminar.) Marky is Shirley Temple’s role for as long as movies live.

And how the boys at Paramount must have crowed over that “Adolph Zukor Presents” line; take that, Fox! If you don’t know what to do with Shirley Temple, stand aside. (Paramount did in fact offer to buy Shirley’s contract for $50,000 outright. Fox declined.) Besides “announcing” Shirley and making her a real star, Little Miss Marker served notice to the geniuses over at Fox that they’d better get off their duffs and come up with something better than that miserable walk-on in Change of Heart. Luckily for Fox, they didn’t waste any more time; they put Shirley in a flurry of tailor-made pictures that are all but unique in the first year of any newborn star — a concentrated series of hits so impossible to ignore that it would spur the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, unsure what else to do, to invent a brand new award category just for her.

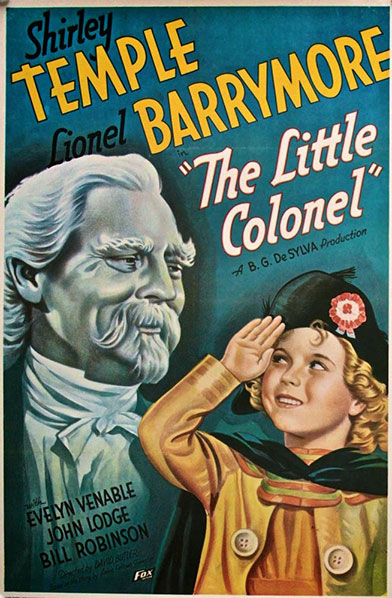

Shirley’s first picture of 1935 was a period piece, her first costume drama as a star. The source material was a children’s book by Annie Fellows Johnston of McCutchanville, Indiana. Mrs. Johnston turned to writing at the age of 29 when her husband died in 1892, leaving her with three small stepchildren to raise on her own. The Little Colonel, published in 1895, was her third novel, and it proved so popular that she wrote a sequel a year until 1907. She wrote, in all, some four dozen books before she died in 1931 at age 68, but The Little Colonel was the only one that was ever filmed. It’s a pity Mrs. Johnston couldn’t have hung on for four more years and seen the apotheosis of her most famous creation.

Shirley’s first picture of 1935 was a period piece, her first costume drama as a star. The source material was a children’s book by Annie Fellows Johnston of McCutchanville, Indiana. Mrs. Johnston turned to writing at the age of 29 when her husband died in 1892, leaving her with three small stepchildren to raise on her own. The Little Colonel, published in 1895, was her third novel, and it proved so popular that she wrote a sequel a year until 1907. She wrote, in all, some four dozen books before she died in 1931 at age 68, but The Little Colonel was the only one that was ever filmed. It’s a pity Mrs. Johnston couldn’t have hung on for four more years and seen the apotheosis of her most famous creation.

In the mid-1950s Republic Pictures was on its last legs as a movie-producing entity. Formed in 1935, it was the brainchild of Herbert J. Yates, founder and president of Consolidated Film Industries, a film processing lab based in New York. Yates saw his big chance when six of Hollywood’s Poverty Row studios — the largest (relatively speaking) being Monogram and Mascot — became deeply indebted to Consolidated for processing fees. Yates called all their debts, then offered an alternative: merge into one production facility, with Yates as head of the studio. The others went for it, and Republic Pictures was born. (In 1937, unable to get along with Yates, Monogram’s officers backed out of the deal and reorganized under their old corporate name, which morphed in 1947 into Allied Artists.)

In the mid-1950s Republic Pictures was on its last legs as a movie-producing entity. Formed in 1935, it was the brainchild of Herbert J. Yates, founder and president of Consolidated Film Industries, a film processing lab based in New York. Yates saw his big chance when six of Hollywood’s Poverty Row studios — the largest (relatively speaking) being Monogram and Mascot — became deeply indebted to Consolidated for processing fees. Yates called all their debts, then offered an alternative: merge into one production facility, with Yates as head of the studio. The others went for it, and Republic Pictures was born. (In 1937, unable to get along with Yates, Monogram’s officers backed out of the deal and reorganized under their old corporate name, which morphed in 1947 into Allied Artists.)

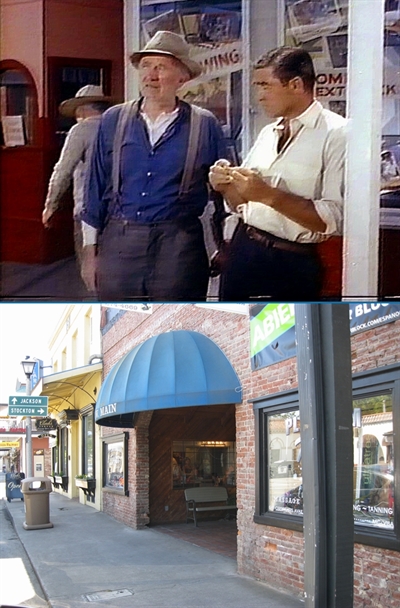

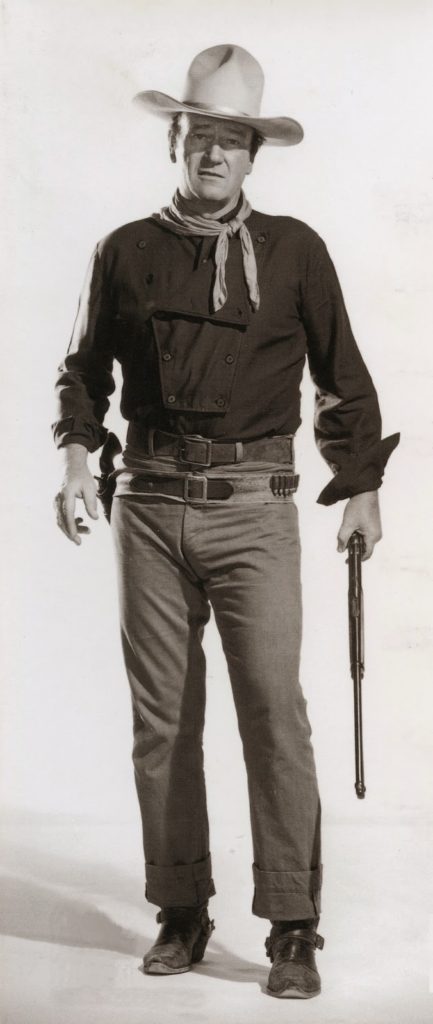

As if Ann Sheridan, and Steve Cochran, and Montgomery Pittman’s intelligent and perceptive script were not enough, there’s another excellent reason to see Come Next Spring, one that all by itself would be more than enough: the extraordinary performance of 13-year-old Sherry Jackson. If Pittman’s script was intended as a showcase for his friend Cochran, it seems to have been equally intended to give Pittman’s own stepdaughter the role of a lifetime. Even by the time Pittman married her mother in 1952, Sherry was already a veteran of more than 15 feature films. Mostly uncredited bits, but more substantial roles were ahead: one of the visionary Portuguese children in The Miracle of Our Lady of Fatima (’52), John Wayne’s daughter in Trouble Along the Way (’53). When shooting started on Come Next Spring, Sherry was coming off her second season as Danny Thomas’s oldest daughter on Make Room for Daddy.

As if Ann Sheridan, and Steve Cochran, and Montgomery Pittman’s intelligent and perceptive script were not enough, there’s another excellent reason to see Come Next Spring, one that all by itself would be more than enough: the extraordinary performance of 13-year-old Sherry Jackson. If Pittman’s script was intended as a showcase for his friend Cochran, it seems to have been equally intended to give Pittman’s own stepdaughter the role of a lifetime. Even by the time Pittman married her mother in 1952, Sherry was already a veteran of more than 15 feature films. Mostly uncredited bits, but more substantial roles were ahead: one of the visionary Portuguese children in The Miracle of Our Lady of Fatima (’52), John Wayne’s daughter in Trouble Along the Way (’53). When shooting started on Come Next Spring, Sherry was coming off her second season as Danny Thomas’s oldest daughter on Make Room for Daddy.

As bad as the Smythes are, they’re not the worst of it. That would be their daughter Joy (Jane Withers), a screaming little monster in a perpetual state of tantrum, and the most misnamed child in the history of human life on Earth.

As bad as the Smythes are, they’re not the worst of it. That would be their daughter Joy (Jane Withers), a screaming little monster in a perpetual state of tantrum, and the most misnamed child in the history of human life on Earth.

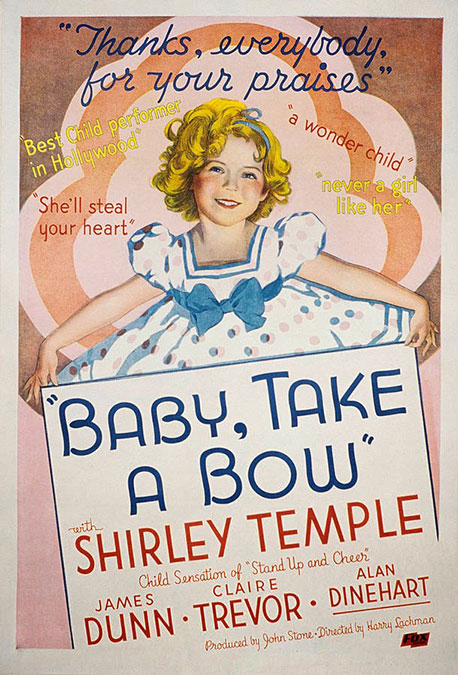

First, an explanation of a trivial point, just so you don’t suspect sloppy copy editing here at Cinedrome. The title of Jay Gorney and Lew Brown’s song “Baby, Take a Bow” has a comma, and the comma appears in this and some other posters, ads and lobby cards for the movie. But it’s not on the picture’s main title card as it appears on screen. Therefore, I’ll be using the comma when referring to the song, but not using it when I’m referring to the movie. Got it?

First, an explanation of a trivial point, just so you don’t suspect sloppy copy editing here at Cinedrome. The title of Jay Gorney and Lew Brown’s song “Baby, Take a Bow” has a comma, and the comma appears in this and some other posters, ads and lobby cards for the movie. But it’s not on the picture’s main title card as it appears on screen. Therefore, I’ll be using the comma when referring to the song, but not using it when I’m referring to the movie. Got it?

Another thread was broken this week that tied the 21st century to the Golden Age of Hollywood. This thread was a thick one, too. Unlike other child stars, including his contemporaries

Another thread was broken this week that tied the 21st century to the Golden Age of Hollywood. This thread was a thick one, too. Unlike other child stars, including his contemporaries

Somehow, this time Gertrude was able to wangle an interview with the movie’s director, Alexander Hall. In Child Star Shirley doesn’t know how Mother did it; I wouldn’t be surprised if word of Shirley’s song-and-dance with James Dunn was already circulating on the Hollywood grapevine. In any event, Shirley auditioned for Hall personally.

Somehow, this time Gertrude was able to wangle an interview with the movie’s director, Alexander Hall. In Child Star Shirley doesn’t know how Mother did it; I wouldn’t be surprised if word of Shirley’s song-and-dance with James Dunn was already circulating on the Hollywood grapevine. In any event, Shirley auditioned for Hall personally.

Little Miss Marker fleshed out and in many ways improved Runyon’s original story. The amnesiac-father angle was always a bit of a credulity stretch; in the movie he becomes a suicide — driven off the end of his rope when the bet he placed with Sorrowful turns out a loser. This heightens Sorrowful’s sense of obligation to Marky: the race was rigged and he knew it when he took the man’s bet. It also links Marky to that losing horse, the ironically named Dream Prince. When Big Steve, Dream Prince’s owner, is suspended over suspicions about that fixed race, Steve and Sorrowful set Marky up as Dream Prince’s dummy owner so the horse can continue to run. Marky’s affection for “the Charger” (another one of her fanciful King Arthur names) draws her, Sorrowful and Bangles closer together, and leads to a crisis when Big Steve gets wind of shenanigans behind his back.

Little Miss Marker fleshed out and in many ways improved Runyon’s original story. The amnesiac-father angle was always a bit of a credulity stretch; in the movie he becomes a suicide — driven off the end of his rope when the bet he placed with Sorrowful turns out a loser. This heightens Sorrowful’s sense of obligation to Marky: the race was rigged and he knew it when he took the man’s bet. It also links Marky to that losing horse, the ironically named Dream Prince. When Big Steve, Dream Prince’s owner, is suspended over suspicions about that fixed race, Steve and Sorrowful set Marky up as Dream Prince’s dummy owner so the horse can continue to run. Marky’s affection for “the Charger” (another one of her fanciful King Arthur names) draws her, Sorrowful and Bangles closer together, and leads to a crisis when Big Steve gets wind of shenanigans behind his back.