It was Merian C. Cooper who came up with the perfect way to introduce Cinerama to audiences. To do it he took a cue from his alter ego Carl Denham in his most famous picture, King Kong, and the way Denham introduced the giant ape to New York.

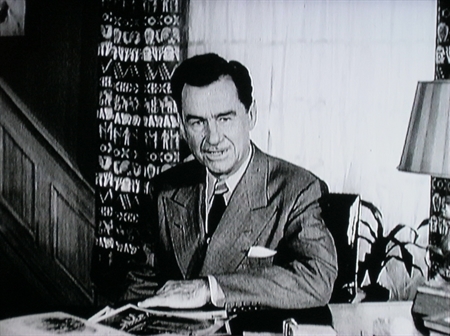

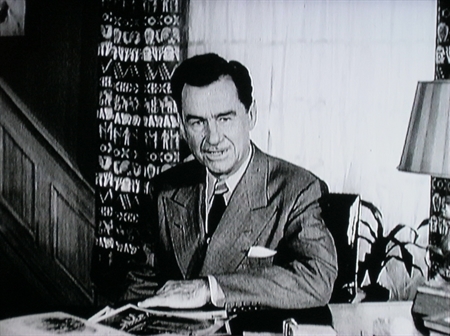

Spectators at that first showing on September 30, 1952 walked into an auditorium dominated by a huge curved wall of wine-red curtains. As the house lights dimmed, they heard the Morse Code dit-dit-ditting that was familiar to them all as the intro to Lowell Thomas’s daily radio program. The red curtains parted slightly, and there was the image of Thomas himself, in black and white, on a standard-size movie screen, welcoming them.

Spectators at that first showing on September 30, 1952 walked into an auditorium dominated by a huge curved wall of wine-red curtains. As the house lights dimmed, they heard the Morse Code dit-dit-ditting that was familiar to them all as the intro to Lowell Thomas’s daily radio program. The red curtains parted slightly, and there was the image of Thomas himself, in black and white, on a standard-size movie screen, welcoming them.

Thomas promised the audience “the latest development in the magic of light and sound.” Then for a full 13 minutes Thomas reviewed the history of moving pictures, from The Great Train Robbery down to 1952. Finally: “The pictures you are now going to see have no plot. They have no stars. This is not a stageplay, nor is it a feature picture, nor a travelogue, nor a symphonic concert, nor an opera. But it is a combination of all of them. In fact, it is the first public demonstration of an entirely new medium. Ladies and gentlemen…This…is Cinerama!”

The curtains rolled open — rolled and rolled and rolled — to the sound of a thundering fanfare that might have accompanied a triumphant army’s march into Ancient Rome, augmented by gasps and squeals from the flabbergasted audience. The screen dissolved from that ordinary little black-and-white image of Lowell Thomas…

…to THIS:

…and that Broadway Theatre audience was taken on an uninterrupted ride in the front seat of the Atom Smasher Rollercoaster at Rockaway, Long Island’s Playland amusement park. “No human being had ever sat in a theater and had this kind of visceral experience,” recalled production manager Jim Morrison. “It hit you right in the gut, right smack in the belly.” And historian Kevin Brownlow: “There was nothing to beat that moment… Suddenly the cinema seemed to open out…the back wall seemed to disappear and we were plunging on a rollercoaster. It was the most staggering moment one could possibly have.”

My own father’s reaction was more succinct. My uncle took him, my mother and my grandparents to see

This Is Cinerama when it opened at San Francisco’s Orpheum Theatre on Christmas Day 1953. As the curtains opened and the rollercoaster burst into view, my father reared back in his seat, his eyes bulging from their sockets, and bellowed at the top of his lungs:

“Jeeee-zuss Christ!!” He may have been more vociferous than anyone else that day, but every single person in the Orpheum had exactly the same reaction. I know because when my own turn to see

This Is Cinerama came 11 years later — even after a decade of CinemaScope, Todd-AO, Panavision, VistaVision, and all the other scopes and visions Cinerama had inspired — that Great Unveiling had lost none of its power. No two ways about it, this was — and remains — the greatest knockout punch in the history of motion pictures.

That first showing had been a mighty near-run thing. The entire feature had never once been run through the projectors — not until the first audience saw it on opening night. With three projectors running in interlocked unison, the standard practice of switching reels every 12 or 13 minutes was clearly out of the question. Special reels, nearly three feet in diameter, had to be built so that each half of the feature could be run without interruption, the only reel change coming during intermission. Two days before the premiere it was discovered that Act II was too long even for those; the film overran the reels by several hundred feet. With no time to make more reels, everybody cringed, rolled their eyes, took a deep breath and decided to hope for the best. They made it almost all the way home — but during the closing credits, the film finally slopped off the take-up reels and jammed the projectors.

Nevertheless, by that time the screening had created such a sensation that those lost last few seconds counted only as a tiny bump in the road to glory. “It was the biggest night I’ve ever seen in pictures,” Merian C. Cooper remembered. “People stayed on the sidewalk by the hundreds till four or five in the morning talking about it. And I knew we had revolutionized the picture business.”

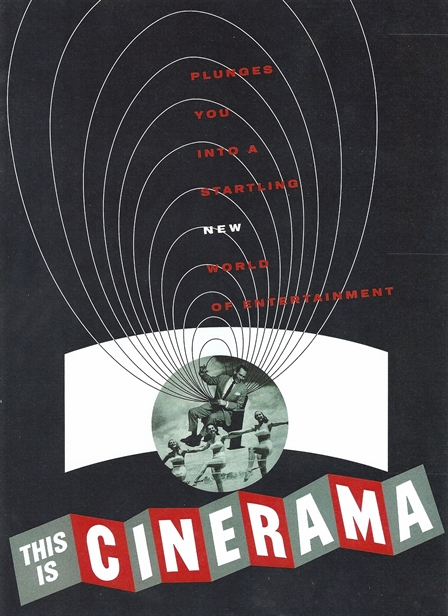

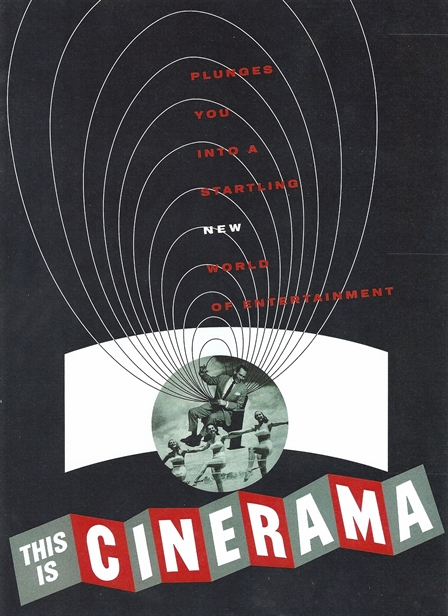

Actually, This Is Cinerama wasn’t really a movie at all; it was an early example of something there wouldn’t even be a term for until decades later: virtual reality. It filled your entire field of vision, 146 degrees left to right, 55 degrees top to bottom (each frame was half again as high as ordinary film, spanning six sprocket holes instead of the standard four). It projected at 26 frames per second instead of 24, lessening the flicker that is always perceived (if only subliminally) by the human eye, and brightening and sharpening the image perceptibly. The sounds didn’t sound recorded at all, and they came from wherever on the screen the images making them were located; musical passages seemed to come from an enormous, invisible orchestra and choir all around you. The postcard image above, an artist’s rendering of the Atom Smasher ride, and the photo on this souvenir program of a theater patron gazing with delight at the bathing beauties water-skiing all around him, are in fact accurate depictions of how audiences perceived the Cinerama experience.

Still, Cooper was right. He and Lowell Thomas and (especially) Fred Waller had revolutionized the picture business. All those Hollywood moguls who had trekked out to Waller’s workshop in Oyster Bay, Long Island, marveling at his demonstration reels but declining to buy into his process, now found themselves scrambling to come up with some variation on Cinerama for themselves. Darryl Zanuck’s 20th Century Fox was first out of the gate in September 1953 with The Robe in CinemaScope (“the poor man’s Cinerama”). Other processes followed, all of them more visually impressive than standard 35mm but none with the sense of audience envelopment Cinerama conveyed; Waller’s process remained the gold standard.

Cinerama entered the culture and the language. There were pop tunes about it (“Oh wide-screen mama/Don’t you Cinerama me…”). The very name Cinerama — a portmanteau word blending “cinema” and “panorama” — influenced American English in ways that haven’t entirely disappeared even now. Everything, it seemed, had its “rama”: laundromats called themselves Launderama; florists had Flowerama; fast-food joints became Burgerama; car dealers became Autorama or Motorama; Kelvinator came out with a Foodarama refrigerator; and, inevitably, burlesque stripper Mavis Rodgers billed herself as “the Sinerama Girl”.

Fred Waller and Hazard Reeves received special Academy Awards at the 1953 ceremony in March 1954, Waller “for designing and developing the multiple photographic and projection systems which culminated in Cinerama”, Reeves for developing “a process of applying stripes of magnetic oxide to motion picture film for sound recording and reproduction.” Two months later, almost to the day, while This Is Cinerama was still playing to sold-out houses at the Broadway Theatre, Fred Waller died of a heart attack at 67. It may seem tragic, to be taken away at the height of his fame after the vindication of his long struggle to bring Cinerama to the public. In fact, however, it was the act of a Merciful Providence. For Waller was spared the heartache of seeing what would become of his brainchild in only ten short years.

Spectators at that first showing on September 30, 1952 walked into an auditorium dominated by a huge curved wall of wine-red curtains. As the house lights dimmed, they heard the Morse Code dit-dit-ditting that was familiar to them all as the intro to Lowell Thomas’s daily radio program. The red curtains parted slightly, and there was the image of Thomas himself, in black and white, on a standard-size movie screen, welcoming them.

Spectators at that first showing on September 30, 1952 walked into an auditorium dominated by a huge curved wall of wine-red curtains. As the house lights dimmed, they heard the Morse Code dit-dit-ditting that was familiar to them all as the intro to Lowell Thomas’s daily radio program. The red curtains parted slightly, and there was the image of Thomas himself, in black and white, on a standard-size movie screen, welcoming them.

My own father’s reaction was more succinct. My uncle took him, my mother and my grandparents to see This Is Cinerama when it opened at San Francisco’s Orpheum Theatre on Christmas Day 1953. As the curtains opened and the rollercoaster burst into view, my father reared back in his seat, his eyes bulging from their sockets, and bellowed at the top of his lungs: “Jeeee-zuss Christ!!” He may have been more vociferous than anyone else that day, but every single person in the Orpheum had exactly the same reaction. I know because when my own turn to see This Is Cinerama came 11 years later — even after a decade of CinemaScope, Todd-AO, Panavision, VistaVision, and all the other scopes and visions Cinerama had inspired — that Great Unveiling had lost none of its power. No two ways about it, this was — and remains — the greatest knockout punch in the history of motion pictures.

My own father’s reaction was more succinct. My uncle took him, my mother and my grandparents to see This Is Cinerama when it opened at San Francisco’s Orpheum Theatre on Christmas Day 1953. As the curtains opened and the rollercoaster burst into view, my father reared back in his seat, his eyes bulging from their sockets, and bellowed at the top of his lungs: “Jeeee-zuss Christ!!” He may have been more vociferous than anyone else that day, but every single person in the Orpheum had exactly the same reaction. I know because when my own turn to see This Is Cinerama came 11 years later — even after a decade of CinemaScope, Todd-AO, Panavision, VistaVision, and all the other scopes and visions Cinerama had inspired — that Great Unveiling had lost none of its power. No two ways about it, this was — and remains — the greatest knockout punch in the history of motion pictures.

Jim, your wonderfully detailed, visceral descriptions of THIS IS CINERAMA is truly the next best thing to being there! What a thrill it must have been for the lucky audiences who got to see it first-hand! You made an excellent point about THIS IS CINERAMA essentially being the first instance of virtual reality. Your blog post makes me wish I had a time machine so I could see …CINERAMA first-hand! Now I'm on tenterhooks for the "heartache" you hinted at (*gulp!*) Great post, as always!

P.S.: As a Stan Freberg fan, I was tickled that you used lyrics from his song "Widescreen Mama, Don't You Cinerama Me! (Cinerama, Cinerama)" 🙂

Thanks, Jim, for another enchanting visit to the world of movie showmanship…this is really the next-best thing to seeing CINERAMA!

Kevin, How the West Was Won was my first Cinerama experience, and I'm one of those who went home with stars in his eyes. It remains my favorite movie to this day. For years, my friends would (barely) conceal their disbelief when I told them — but I was coasting on the memory of Cinerama, while they could only judge by the general-release version or (worse yet) home video; in time I became a little embarrassed about saying so. When I saw HTWWW again in Cinerama in 1996 — for the first time in 34 years — I realized I had nothing to be embarrassed about.

I refuse to do roller coasters in real life, but I could probably be talked into seeing "This is Cinerama". Riding a roller coaster from the safety of my theater seat is tolerable for me.

Alas, I've never experienced Cinerama, but I hope to one day. I do like the Tiomkin music for "Search for Paradise" as gloriously overblown as it is.

I know people who trekked to see "How the West Was Won" at a Cinerama theater in Ohio, and came back with stars in their eyes.

Thanks, Silver! Yes, one can only imagine how TIC looked in 1952, when even Technicolor was still something of an exotic treat. (Must ask my uncle why I wasn't included in his Cinerama party; I'd have been good.)

But I can vouch for the experience from '63 onward. No matter how jaded you think you are from IMAX and whatever, that rollercoaster still wows 'em. What Jim Morrison says in my post is not a figure of speech, it literally hits you in the gut, right smack in the belly. You can feel everything but the wind on your face.

Wow! I would have LOVED to have seen "This is Cinerama" in the theatre when it first came out. Fantastic! The way you write about it is the next best thing to being there.