The first silent of the weekend was The Prairie Pirate (1925), a Harry Carey western, and far from his best. (You can always tell that a movie star has really arrived when they’re expected to carry a story like this. By 1925 Harry Carey had not only arrived, he’d definitely set up housekeeping.) Carey played Brian Delaney, a cattle rancher in Old California who comes home one day to find that his sister Ruth (Jean Dumas), besieged in their isolated home by marauding bandits, has committed suicide rather than submit to a fate worse than death. The only clues: a hasty note from Ruth telling Brian “they’ll never take me ali–” and some distinctive black cigarette butts. (Ruth actually knew the outlaw leader’s name, Aguilar, but somehow neglected to include it in her note.)

The first silent of the weekend was The Prairie Pirate (1925), a Harry Carey western, and far from his best. (You can always tell that a movie star has really arrived when they’re expected to carry a story like this. By 1925 Harry Carey had not only arrived, he’d definitely set up housekeeping.) Carey played Brian Delaney, a cattle rancher in Old California who comes home one day to find that his sister Ruth (Jean Dumas), besieged in their isolated home by marauding bandits, has committed suicide rather than submit to a fate worse than death. The only clues: a hasty note from Ruth telling Brian “they’ll never take me ali–” and some distinctive black cigarette butts. (Ruth actually knew the outlaw leader’s name, Aguilar, but somehow neglected to include it in her note.)

In the next scene — the reason why is unexplained — Brian has become an outlaw calling himself the Yellow Seal. His life of crime consists mainly of raiding saloons all around the area and confiscating the establishments’ cigarette butts (actual title card: “Now bring me every ash tray in the place — muy pronto!“). This heinous spree of wanton lawlessness has put a $5,000 price on his head, dead or alive — a pretty draconian bounty for cleaning out ash trays, I’d say.

At the same time, Brian (as the Yellow Seal) meets and romances the daughter (Trilby Clark) of a local ranchero (Robert Edeson). She in turn is being coerced into marrying a saloon owner (Lloyd Whitlock) who has won her father’s hacienda at his crooked gaming tables — and who is also in cahoots with the bandit Aguilar.

Harry Carey is always welcome, of course, but that’s about as much time as we need to spend on this nonsense. Carey gets to do some nifty riding and fighting, though both he and Trilby Clark are all-too-clearly doubled in the picture’s barreling-downstream-toward-the-waterfall climax (which comes to an awfully hasty resolution; did they run out of money in 1925, or is footage missing now?).

The next two movies on the program were considerably more rewarding. First came Sunbonnet Sue (1945), a modest but entirely winning little Gay Nineties musical from Monogram Pictures. An ebullient Gale Storm played the title character, setting out on a showbiz career by singing in a Bowery saloon run by her father (George Cleveland) — to the horror of her stuffy Fifth Avenue aunt (Edna Holland), who vows to torpedo this vulgar stain on the family honor before it exposes her own humble roots. Monogram’s entry in the spate of nostalgic turn-of-the-20th-century musicals epitomized by Meet Me in St. Louis over at MGM, Sunbonnet Sue had enough charm to make you wish that the studio had shaken off Poverty Row altogether and sprung for a color production — if not Technicolor, then maybe Cinecolor or one of the other bargain-basement processes. Oh well, baby steps — Monogram was hoping to move into A-pictures eventually, but it wouldn’t do to go too far too fast. Still, Sunbonnet Sue was a nice effort, leaning heavily on old songs that, if not yet in the public domain, were at least well-worn enough that the rights could be had for…well, for a song. The picture even managed to snag an Oscar nomination for Edward J. Kay’s musical scoring (it lost to MGM’s Anchors Aweigh).

The next two movies on the program were considerably more rewarding. First came Sunbonnet Sue (1945), a modest but entirely winning little Gay Nineties musical from Monogram Pictures. An ebullient Gale Storm played the title character, setting out on a showbiz career by singing in a Bowery saloon run by her father (George Cleveland) — to the horror of her stuffy Fifth Avenue aunt (Edna Holland), who vows to torpedo this vulgar stain on the family honor before it exposes her own humble roots. Monogram’s entry in the spate of nostalgic turn-of-the-20th-century musicals epitomized by Meet Me in St. Louis over at MGM, Sunbonnet Sue had enough charm to make you wish that the studio had shaken off Poverty Row altogether and sprung for a color production — if not Technicolor, then maybe Cinecolor or one of the other bargain-basement processes. Oh well, baby steps — Monogram was hoping to move into A-pictures eventually, but it wouldn’t do to go too far too fast. Still, Sunbonnet Sue was a nice effort, leaning heavily on old songs that, if not yet in the public domain, were at least well-worn enough that the rights could be had for…well, for a song. The picture even managed to snag an Oscar nomination for Edward J. Kay’s musical scoring (it lost to MGM’s Anchors Aweigh).

Next, after the Thursday dinner break, came the genuinely unusual, little-seen To Mary — with Love (1936). Based on a two-part novella by Richard Sherman that appeared in The Saturday Evening Post in late 1935, the picture told the story of a marriage, or at least the first ten years of it (which for a while look like they will be the last ten years of it). We first meet Jock and Mary Wallace (Warner Baxter and Myrna Loy) on the evening of their wedding day — which also happens to be Election Night 1925, so their own little after-wedding party at the Waldorf-Astoria hotel is swamped by a much bigger party celebrating the election of Jimmy Walker as mayor of New York. Helping them celebrate is Bill Hallam (Ian Hunter), Jock’s best man (and a silent torch-bearer for Mary) and a young woman the three have just met that night, Kitty Brant (Claire Trevor), who will become an intimate friend — at one point, perhaps a little too intimate.

Next, after the Thursday dinner break, came the genuinely unusual, little-seen To Mary — with Love (1936). Based on a two-part novella by Richard Sherman that appeared in The Saturday Evening Post in late 1935, the picture told the story of a marriage, or at least the first ten years of it (which for a while look like they will be the last ten years of it). We first meet Jock and Mary Wallace (Warner Baxter and Myrna Loy) on the evening of their wedding day — which also happens to be Election Night 1925, so their own little after-wedding party at the Waldorf-Astoria hotel is swamped by a much bigger party celebrating the election of Jimmy Walker as mayor of New York. Helping them celebrate is Bill Hallam (Ian Hunter), Jock’s best man (and a silent torch-bearer for Mary) and a young woman the three have just met that night, Kitty Brant (Claire Trevor), who will become an intimate friend — at one point, perhaps a little too intimate.

From there the picture follows the ups and downs of the Wallace marriage for the next ten years, with major moments set against a background of significant events in America — the Dempsey/Tunney fight, Charles Lindbergh’s flight to Paris, the 1929 stock market crash, etc. Through it all, Bill Hallam is Jock and Mary’s staunch friend, conscience and protector, helping them navigate the rough spots (and some of them are rough indeed), despite the fact that he’s in love with Mary and she knows it. Well-directed by John Cromwell, To Mary — with Love told its story straightforwardly and with a refreshing (not to say astonishing) lack of melodrama or soap opera. Baxter, Loy and Hunter each gave one of their personal-best performances. According to the program notes by Richard Barrios (who also introduced the screening), this unique picture has been kept out of circulation for decades, apparently because of issues concerning the rights to Richard Sherman’s original story, so this screening at Cinevent was a rare opportunity to catch up with it.

Another near-lost picture was the Laurel and Hardy short Duck Soup (1927) (not to be confused with the Marx Brothers feature). This one was believed lost for years, which was a pity, until a print surfaced in Belgium in 1974, which was a blessing, because it’s probably the earliest short in which The Boys played something like the characters they would soon become famous for.

After that it was yet another picture based on a Saturday Evening Post story (“The Spoils of War” by Hugh Wiley). This was Behind the Front (1926), a Paramount silent comedy starring Wallace Beery and Raymond Hatton as soldiers who become best friends in the trenches of World War I, never suspecting that Hatton is the pickpocket who stole Beery’s watch, and whom Beery was chasing until they both got sidetracked into enlisting. What I saw looked pretty good, but a little Wallace Beery goes a long way with me, so I watched a little, then bailed out to browse the dealers’ room until they closed.

Besides, I didn’t want to miss the last movie of the day, The Amazing Mr. Williams (1939); the thought of Melvyn Douglas and Joan Blondell in the same picture was just too good to pass up. This was one of Columbia’s entries in Hollywood’s many efforts to duplicate the combination of sophisticated banter and murder-mystery suspense of William Powell and Myrna Loy in the Thin Man movies. This time, Douglas played an ace police detective who can solve the toughest cases in nothing flat; Blondell was his fiancée, the mayor’s secretary, ever getting stood up when he’s called away on yet another important case. Both of them get embroiled in the case at hand — which defies easy synopsis, so I won’t even try. Anyhow, the mystery was complicated enough to hold the interest, the love-play amusing, and the supporting cast stalwart: Clarence Kolb as Douglas’s conniving boss, Ruth Donnelly as (what else?) the heroine’s wise-cracking best friend, Jonathan Hale as the mayor, Edward Brophy, Donald MacBride, Don Beddoe, John Wray. Nobody, no studio, was ever quite able to duplicate that Thin Man magic, but watching them try made for a lot of fun in the 1930s and ’40s, and this was a good example.

Besides, I didn’t want to miss the last movie of the day, The Amazing Mr. Williams (1939); the thought of Melvyn Douglas and Joan Blondell in the same picture was just too good to pass up. This was one of Columbia’s entries in Hollywood’s many efforts to duplicate the combination of sophisticated banter and murder-mystery suspense of William Powell and Myrna Loy in the Thin Man movies. This time, Douglas played an ace police detective who can solve the toughest cases in nothing flat; Blondell was his fiancée, the mayor’s secretary, ever getting stood up when he’s called away on yet another important case. Both of them get embroiled in the case at hand — which defies easy synopsis, so I won’t even try. Anyhow, the mystery was complicated enough to hold the interest, the love-play amusing, and the supporting cast stalwart: Clarence Kolb as Douglas’s conniving boss, Ruth Donnelly as (what else?) the heroine’s wise-cracking best friend, Jonathan Hale as the mayor, Edward Brophy, Donald MacBride, Don Beddoe, John Wray. Nobody, no studio, was ever quite able to duplicate that Thin Man magic, but watching them try made for a lot of fun in the 1930s and ’40s, and this was a good example.

So opening day of Cinevent drew to a close. On to Day 2, Friday, next time.

Cinevent this year began with something new: A tour of Columbus’s Ohio Theatre. The tour cost extra, and ran late enough to conflict with the first show in the screening room — but it was worth it on both counts.

Cinevent this year began with something new: A tour of Columbus’s Ohio Theatre. The tour cost extra, and ran late enough to conflict with the first show in the screening room — but it was worth it on both counts. As I said before, the Ohio Theatre tour ran long enough that I missed the first event in the screening room, Chapters 1-3 of this year’s serial, Republic’s

As I said before, the Ohio Theatre tour ran long enough that I missed the first event in the screening room, Chapters 1-3 of this year’s serial, Republic’s  After Hawk of the Wilderness came the first feature film of this year’s Cinevent: John Ford’s

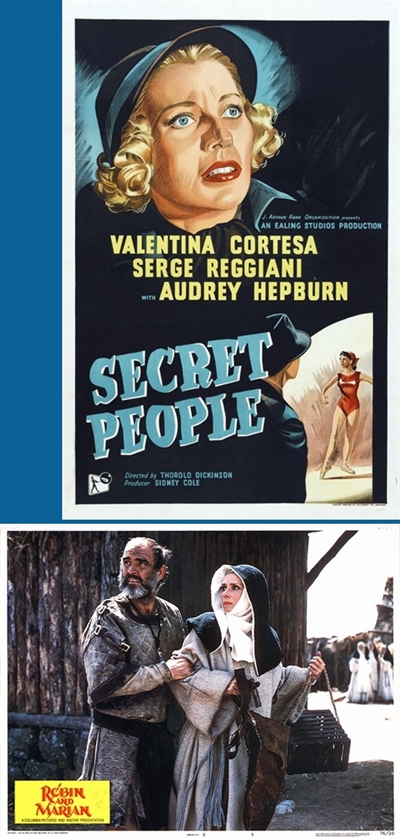

After Hawk of the Wilderness came the first feature film of this year’s Cinevent: John Ford’s  Once again, on the Wednesday night before the first day of Cinevent, some of us early arrivals in Columbus attended a screening at the Wexner Center for the Arts on the Ohio State Campus. The theme this year was “Audrey Hepburn X 2”, and the program consisted of pictures at opposite ends of Audrey’s career, one of her last (Robin and Marian, 1976) followed by one of her first (Secret People, 1952). Personally, I would have preferred that the Wexner Center take the program in chronological order rather than the reverse.

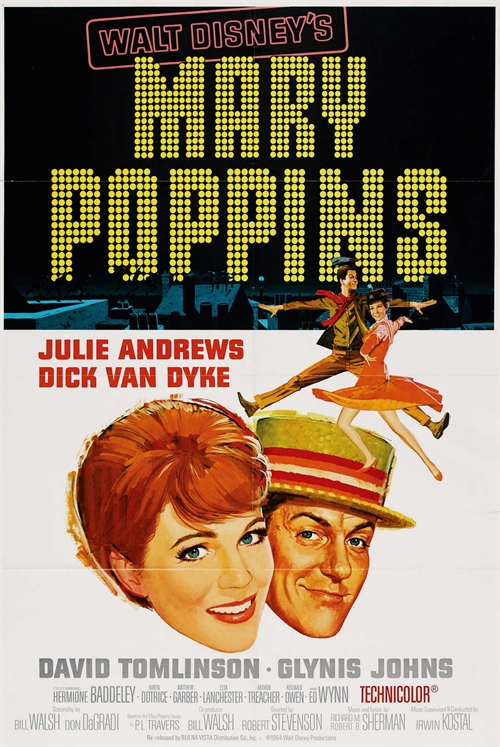

Once again, on the Wednesday night before the first day of Cinevent, some of us early arrivals in Columbus attended a screening at the Wexner Center for the Arts on the Ohio State Campus. The theme this year was “Audrey Hepburn X 2”, and the program consisted of pictures at opposite ends of Audrey’s career, one of her last (Robin and Marian, 1976) followed by one of her first (Secret People, 1952). Personally, I would have preferred that the Wexner Center take the program in chronological order rather than the reverse. “G’bye, Mary Poppins,” says Dick Van Dyke’s Bert as the Practically Perfect Nanny sails away from No. 17 Cherry Tree Lane in Walt Disney’s Mary Poppins (1964). “Don’t stay away too long…”

“G’bye, Mary Poppins,” says Dick Van Dyke’s Bert as the Practically Perfect Nanny sails away from No. 17 Cherry Tree Lane in Walt Disney’s Mary Poppins (1964). “Don’t stay away too long…” Before I get to Mary Poppins, a few words about Walt Disney. In the community college Film History and Introduction to Film classes I teach, I have a standard lecture I deliver when the subject comes up, as it always will, of Disney’s place in the art and history of moving pictures. Generally, that lecture runs something like this:

Before I get to Mary Poppins, a few words about Walt Disney. In the community college Film History and Introduction to Film classes I teach, I have a standard lecture I deliver when the subject comes up, as it always will, of Disney’s place in the art and history of moving pictures. Generally, that lecture runs something like this: I transition now from my classroom lecture on Walt Disney back to a consideration of his final masterpiece.

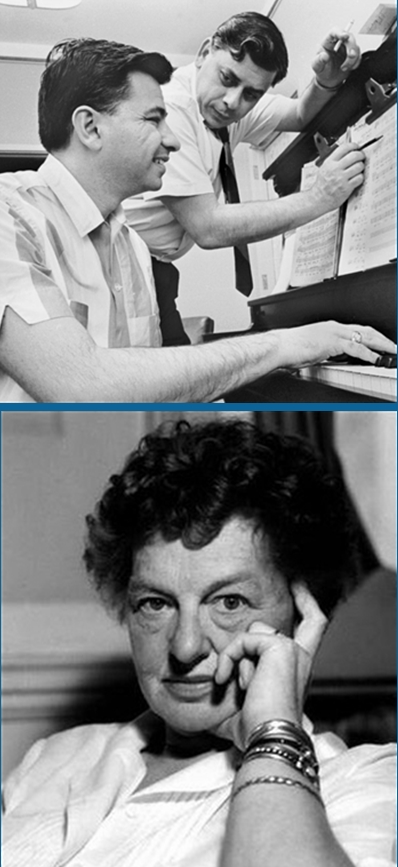

I transition now from my classroom lecture on Walt Disney back to a consideration of his final masterpiece.  And this brings me to Walt Disney’s secret weapon on Mary Poppins. Or weapons, I should say: Robert B. and Richard M. Sherman. Like writer Lawrence Edward Watkin on

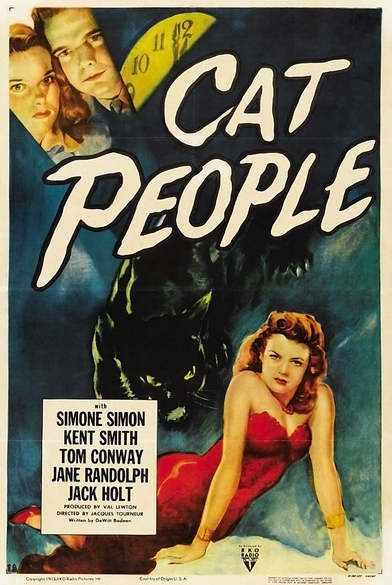

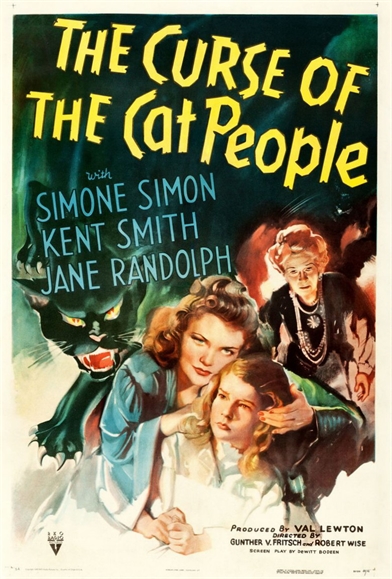

And this brings me to Walt Disney’s secret weapon on Mary Poppins. Or weapons, I should say: Robert B. and Richard M. Sherman. Like writer Lawrence Edward Watkin on  Producer Val Lewton was noted for his “psychological” horror movies, replacing the usual movie vampires, werewolves and other monsters with explorations of the darker reaches of the human psyche. We saw five of Lewton’s movies in class: Cat People (1942, d: Jacques Tourneur), I Walked with a Zombie (1943, d: Tourneur), The Curse of the Cat People (1944, d: Gunther von Fritsch, Robert Wise), The Body Snatcher (1945, d: Wise) and Isle of the Dead (1945, d: Mark Robson). Discuss the psychological aspects of

Producer Val Lewton was noted for his “psychological” horror movies, replacing the usual movie vampires, werewolves and other monsters with explorations of the darker reaches of the human psyche. We saw five of Lewton’s movies in class: Cat People (1942, d: Jacques Tourneur), I Walked with a Zombie (1943, d: Tourneur), The Curse of the Cat People (1944, d: Gunther von Fritsch, Robert Wise), The Body Snatcher (1945, d: Wise) and Isle of the Dead (1945, d: Mark Robson). Discuss the psychological aspects of  Irena has spent her whole life trying to suppress her emotions and “dark” feelings because that is what she has learned to do, which is unhealthy; this becomes her downfall in a way. Instead of being nurtured, encouraged, or listened to, Irena is forced to live in a cage her entire life, feeling as though she cannot escape from the prison of her mind. When she dies, she is finally free from the evils that plague her.

Irena has spent her whole life trying to suppress her emotions and “dark” feelings because that is what she has learned to do, which is unhealthy; this becomes her downfall in a way. Instead of being nurtured, encouraged, or listened to, Irena is forced to live in a cage her entire life, feeling as though she cannot escape from the prison of her mind. When she dies, she is finally free from the evils that plague her. Furthermore, in The Curse of the Cat People, the sequel to Cat People, we see Irena’s husband Oliver is now married to his co-worker Alice, and has a daughter with her named Amy (Ann Carter). Amy is perceived as a strange, imaginative girl who daydreams about fantastical and magical things. The other children believe her to be weird because of her airy personality and short attention span. She later befriends an old lady, Mrs. Farren (Julia Dean), with a jealous daughter Barbara (Elizabeth Russell), and even creates an imaginary friend who takes the form of Irena, her father’s first wife. Again, instead of choosing to understand his daughter, Oliver firmly tells her she must go play with the other kids or she will be punished. He also condemns her for having an imaginary friend, and she is severly punished for that as well.

Furthermore, in The Curse of the Cat People, the sequel to Cat People, we see Irena’s husband Oliver is now married to his co-worker Alice, and has a daughter with her named Amy (Ann Carter). Amy is perceived as a strange, imaginative girl who daydreams about fantastical and magical things. The other children believe her to be weird because of her airy personality and short attention span. She later befriends an old lady, Mrs. Farren (Julia Dean), with a jealous daughter Barbara (Elizabeth Russell), and even creates an imaginary friend who takes the form of Irena, her father’s first wife. Again, instead of choosing to understand his daughter, Oliver firmly tells her she must go play with the other kids or she will be punished. He also condemns her for having an imaginary friend, and she is severly punished for that as well.