Apologies for the delay, Cinedrome readers. I’ve been on vacation, but now I’m back and ready to resume my recap of this year’s Cinevent.

Apologies for the delay, Cinedrome readers. I’ve been on vacation, but now I’m back and ready to resume my recap of this year’s Cinevent.

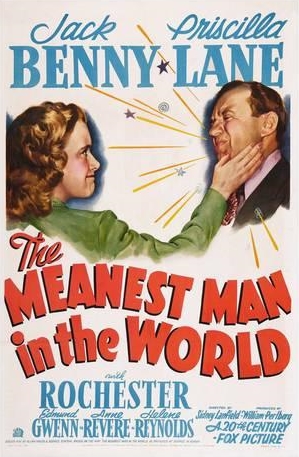

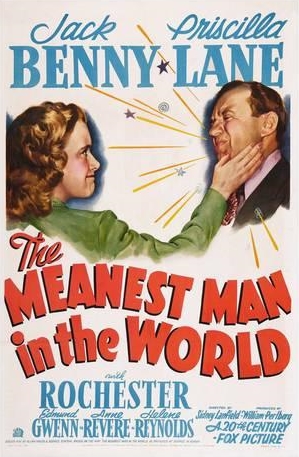

After The War of the Worlds on Saturday afternoon, Leonard Maltin introduced The Meanest Man in the World (1943) with Jack Benny. Sharing above-the-title billing with him was the ever-fetching Priscilla Lane, but as anyone who remembers Benny’s radio or TV shows will know, his real co-star was Eddie “Rochester” Anderson (here billed only by his nom de radio).

Benny played Richard Clarke, a tender-hearted small-town lawyer who moves to New York, leaving sweetheart Janie (Lane) back home while he makes his fortune — which his manservant Shufro (Anderson) persuades him he’ll never do until he stops being such a darn nice guy. So he decides to become a first-class heel — but, as this poster suggests, that only puts him in danger of losing his girlfriend.

The two men may have sported different names in the movie, but it was business as usual for Jack Benny and Rochester, with Rochester/Shufro getting most of the funny lines and staying always one step ahead of his boss. Directed by Sidney Lanfield (who always knew how to stay out of the way), the movie clocked in at only 57 minutes, which made it play more or less like an hour-long episode of The Jack Benny Program, and a pretty funny one at that. An unexpected surprise was Anne Revere as Benny’s secretary. I’ve been more accustomed to see her in dead-serious roles as somebody’s dogged no-nonsense mother (Jennifer Jones in The Song of Bernadette, Elizabeth Taylor in National Velvet, Gregory Peck in Gentleman’s Agreement, Montgomery Clift in A Place in the Sun), but here she was a wisecracking office assistant (she reminded me of Ann B. Davis’s Schultzy on the old Bob Cummings Show), and she was hilarious. I never knew she had it in her.

Just before the dinner break came the third and final tribute to one of Cinevent’s founders. This time it was for John Baker, and the program consisted of 15 jazz soundies of the type Mr. Baker once so diligently collected. “Soundies”, for those who don’t know, were two-to-three minute filmed musical performances — forerunners, if you will, of music videos — that were shot on 16mm and played in specially designed jukeboxes. Their heyday wasn’t long, but there were many of them made while the fad lasted. Mr. Baker himself accumulated thousands of them, eventually selling his collection to the University of Kansas and the American Jazz Museum (thus funding his retirement to Florida). I don’t know whether any of the soundies shown at Cinevent were actually from his former collection, but they were the sort of things he would certainly have had, and the artists ranged from the near-forgotten (Apos & Estrellita, Dewey Brown, The Delta Rhythm Boys) to the full-out-legendary (Cab Calloway, Noble Sissle, Nat “King” Cole, Fats Waller, Count Basie).

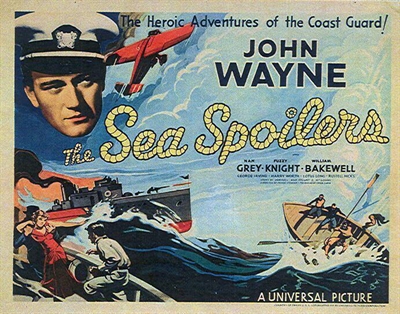

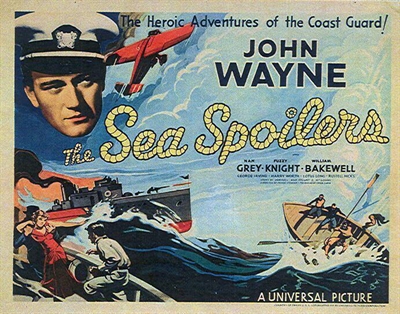

After dinner it was The Sea Spoilers (1936), one of the B-pictures John Wayne made at Universal in an effort to break out of the horse-opera ghetto he was mired in at Republic and for fly-by-night producer Paul Malvern. Two years ago Cinevent presented probably the best of these, California Straight Ahead, but all of them were pretty good. Sea Spoilers had the Duke as a U.S. Coast Guard officer on the trail of seal poachers led by Russell Hicks, with his sweetheart Nan Gray caught in the crossfire.

After dinner it was The Sea Spoilers (1936), one of the B-pictures John Wayne made at Universal in an effort to break out of the horse-opera ghetto he was mired in at Republic and for fly-by-night producer Paul Malvern. Two years ago Cinevent presented probably the best of these, California Straight Ahead, but all of them were pretty good. Sea Spoilers had the Duke as a U.S. Coast Guard officer on the trail of seal poachers led by Russell Hicks, with his sweetheart Nan Gray caught in the crossfire.

Then came Richard Talmadge in the silent The Speed King (1923), a variation on The Prisoner of Zenda that had him as an American motorcycle racer dragooned into impersonating a lookalike king in one of those tiny kingdoms where stories like this always take place. Talmadge (no relation to sisters Norma, Constance and Natalie — in fact, his given name was Sylvester Metz) was an appealing sort who had a brief run as an actor but a long one as stuntman, stunt coordinator, second unit director and other miscellaneous crew functions. Henry Hathaway employed him often, from The Trail of the Lonesome Pine to How the West Was Won; he can be seen (if you know where to look) doubling for Lionel Barrymore in his more strenuous scenes in Hathaway’s masterpiece Down to the Sea in Ships. (And say, Cinevent folks, how about showing that one one of these years?)

Next was, for many of those in attendance, the highlight of the whole weekend: 1946’s Three Little Girls in Blue. (Personally, I’d put it neck-and-neck with The War of the Worlds, but that could just be me.) As I’ve mentioned before, this was 20th Century Fox’s second remake of their own Three Blind Mice from 1938 (the first remake, in 1941, was the Betty Grable vehicle Moon Over Miami), about three sisters living high on a modest inheritance, hoping to land rich husbands before the money runs out. It’s a movie of immense charm and constant pleasures that deserves to be better known.

Next was, for many of those in attendance, the highlight of the whole weekend: 1946’s Three Little Girls in Blue. (Personally, I’d put it neck-and-neck with The War of the Worlds, but that could just be me.) As I’ve mentioned before, this was 20th Century Fox’s second remake of their own Three Blind Mice from 1938 (the first remake, in 1941, was the Betty Grable vehicle Moon Over Miami), about three sisters living high on a modest inheritance, hoping to land rich husbands before the money runs out. It’s a movie of immense charm and constant pleasures that deserves to be better known.

The print shown this year was the same one Cinevent screened in 1998; genuine IB Technicolor — as such, guaranteed never to fade — and in the same impeccable physical condition as 20 years ago, with hardly a splice, line, or scratch from first frame to last.

This is important to note because the DVD available from the 20th Century Fox Cinema Archives collection is distinctly inferior. Fox turned out the best specimens of Technicolor in the 1940s, but you wouldn’t always know it from the quality of their DVD releases. They’ve been very uneven, and Three Little Girls, alas, is way at the low end of the scale. I mentioned a while back that this is probably the best Fox musical that didn’t involve Betty Grable, Alice Faye, Shirley Temple or Rodgers and Hammerstein, and it’s probably no coincidence that those names are on the best examples of Fox Tech on DVD (Moon Over Miami; Hello, Frisco, Hello; The Little Princess; State Fair). It’s a shame Three Little Girls in Blue didn’t get similar care, because the color really is lovely — and, in Vera-Ellen’s fantasy dance to “You Make Me Feel So Young”, pretty striking. And Celeste Holm’s red dress as she sings “Always a Lady” is enough to knock your eyes out. If you were lucky enough to see it this year (or 20 years ago) at Cinevent. Kudos and thanks to the unidentified source of that print. (And by the way, the lobby card reproduced here is a classic example of false advertising. You’d never guess, would you, that the picture takes place in 1902?)

Finally, it pains me to say this, but I had to miss the last screening of Day 3, 1935’s Murder by Television with Bela Lugosi and June Collyer. The spirit was willing, but the start time was 12:20 a.m. Sunday morning, and I had to call it a day. I’ll just have to catch up with that intriguing curiosity some other day.

* * *

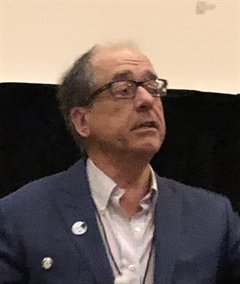

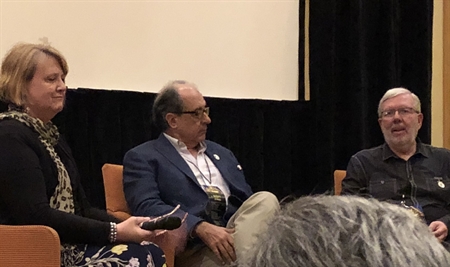

Now I want to double back to that afternoon conversation between Scott Eyman and Leonard Maltin. I wasn’t able to record the whole hour’s talk (I trust somebody did), but I did catch a few interesting remarks from these articulate gentlemen. First, moderator Caroline Breder-Watts asked Leonard what first got him hooked on movies; “What was it that caused that spark for you, for film?”

L.M.: I think it was the fact that when I was growing up in the ’50s and ’60s, television was a living museum of movies. And being a Baby Boomer, I became a TV addict, and at that time — I’m not telling you guys anything you don’t know; if there were younger people here I’d have to explain it a little more fully — but I watched Laurel and Hardy every day, every day of my life growing up. The Little Rascals, every day. Walt Disney every week. At one golden period, The Mickey Mouse Club every afternoon. All of these things left a deep, deep impression on me, and they’re still the things I care about most today. So I think it all began there.

L.M.: I think it was the fact that when I was growing up in the ’50s and ’60s, television was a living museum of movies. And being a Baby Boomer, I became a TV addict, and at that time — I’m not telling you guys anything you don’t know; if there were younger people here I’d have to explain it a little more fully — but I watched Laurel and Hardy every day, every day of my life growing up. The Little Rascals, every day. Walt Disney every week. At one golden period, The Mickey Mouse Club every afternoon. All of these things left a deep, deep impression on me, and they’re still the things I care about most today. So I think it all began there.

C.B.-W.: Were those experiences you shared with your parents, with your family, or was that something that was more solitary for you?

L.M.: You know, I honestly don’t remember. We only had one TV I think at that time. Imagine the deprivation! So I guess we must have watched a lot of it. But a lot of it was early morning, late afternoon after school, you know, Saturday morning, all of that. So those were “kid time”.

C.B.-W.: I think there is something to be mourned in that we don’t have that communal experience at home anymore with all our devices and all our tablets and all of our things. I was in the same situation when I was a kid, I watched kind of what my parents watched — but that was a good thing, ’cause they watched really good things. And they watched old movies, and that’s where I got my spark from. And that’s not an experience we all have any more. There’s channels for children, there’s all kind of different distractions, that sort of thing.

L.M.: There’s fragmentation, and narrow-casting, too. When I was growing up you didn’t have to go to Turner Classic Movies, the sole channel on the dial — “dial”! — you didn’t have to go someplace to see old movies. You just had to switch the channel, because this channel would be showing a W.C. Fields movie, and this one might be showing a Bogart movie, and this one might be showing Charlie Chan, or something like that. They were everywhere. They were unavoidable, I guess is what I’m saying, it was unavoidable to see old movies at that time.

C.B.-W.: Scott, I know this convention, this festival in particular had a big part of your upbringing, didn’t it?

C.B.-W.: Scott, I know this convention, this festival in particular had a big part of your upbringing, didn’t it?

S.E.: Yeah, unlike Leonard — let’s see, you grew up in Teaneck [New Jersey], so you had WOR, and you had the Million Dollar Movie, and you had all these New York stations that were churning films all the time. I grew up in Cleveland — please, no hatred [laughter] — and the only thing we had was the Paramount package from the 1930s. So I saw W.C. Fields and a few other things, but there wasn’t a lot there. I didn’t get that immersion that you did. What did it for me was two movies, actually. Harold Lloyd’s World of Comedy in 1962 or ’63; I think it was ’63 when I saw it, so I would have been 11. I’d seen some, like, “funny man” TV series and clips, Flicker Flashback, things like that on television, and this silent thing interested me. So I conned my grandmother into taking me to see Harold Lloyd’s World of Comedy, which was in a theater which was in what is euphemistically referred to in that area as a “changing neighborhood”. She wouldn’t go in, because God only knows what would happen if she went in and had to sit in a dark theater in a changing neighborhood. So she dropped me off, and she stayed in the car for two hours while I was inside the theater, so in case I came out I wouldn’t be attacked and murdered in the 20 feet between the doors and the car. I went and saw Harold Lloyd’s World of Comedy, and that intrigued me sociologically. That’s not a word I would have applied at the age of 11 or 12, but you know, the clothes, the cars, the buildings, it was so different than what I saw around me. Also, of course, the gags, the structure, how he worked comedically, as opposed to the people I was seeing on television like Jack Benny. It was a different vibe, it was visual as opposed to verbal.

And then the second one that got me — you’ll laugh — was The Sons of Katie Elder about a year later, about ’64, which I went in to see, it was on a double bill with The Family Jewels at the Center Mayfield Theatre. Do you guys remember the theater where you saw movies? I can remember exactly which theater I saw every movie I’ve ever seen at.

L.M.: Me too, and I wonder if today’s generation can possibly have that same feeling about having seen a movie in Multiplex 4.

S.E.: No, no. But I went in to see Sons of Katie Elder and it was crowded so I had to sit way down in front, like four or five rows from the front row. I usually sat in the middle, but here I was stuck in the front of the theater looking up like this, and I suddenly noticed the grain in the film. And the grain was alive, and the film was alive. On one hand I was watching the story and the acting — it’s a good movie — but I was also watching the film itself as it sped through the projector. And I had this interesting sensation of watching a living organism unfold; it was like microphotography in a National Geographic special. So it was a two-part thing. The Harold Lloyd thing gave me a sense of film as a window into the past, and at this point I wanted to be an archaeologist, and The Sons of Katie Elder gave me a sense of film as a living organism that is constructed, and architected, and planned. Those two things combined in this pincer movement for me.

* * *

[Later, Ms. Breder-Watts asked how the love of watching movies led them to transition into writing about them]:

L.M.: Actually, I started writing letters, that’s where it began. I wrote fan letters; I was big on that. I got some wonderful, wonderful answers. My first ambition had been to be a cartoonist, and I wrote to some of my heroes. I wanted to be a cartoonist and I sent some of my samples to Charles Schulz, who wrote back the kindest, most encouraging letter, very supportive. A personal letter, not a form letter, just a wonderful gesture on his part. And he included in the package an original signed daily Peanuts strip. Unsolicited. P.S., 30 years later I got hired by United Media, his syndicator, to interview him in his studio in Santa Rosa, Calif., for a video that was going to accompany a traveling museum tour. So as they’re getting the cameras set I told him that story. He jumped out of his seat, he says, “We gotta get you something newer!” He went over to one of his work tables and sifted through his Sunday pages, found a more recent original Sunday India ink page, and signed it this time for Alice [Mrs. Maltin] and me, and signed it “Sparky”, which was his nickname with his friends. So sometimes luck and timing and coincidence play a role in all of this.

L.M.: Actually, I started writing letters, that’s where it began. I wrote fan letters; I was big on that. I got some wonderful, wonderful answers. My first ambition had been to be a cartoonist, and I wrote to some of my heroes. I wanted to be a cartoonist and I sent some of my samples to Charles Schulz, who wrote back the kindest, most encouraging letter, very supportive. A personal letter, not a form letter, just a wonderful gesture on his part. And he included in the package an original signed daily Peanuts strip. Unsolicited. P.S., 30 years later I got hired by United Media, his syndicator, to interview him in his studio in Santa Rosa, Calif., for a video that was going to accompany a traveling museum tour. So as they’re getting the cameras set I told him that story. He jumped out of his seat, he says, “We gotta get you something newer!” He went over to one of his work tables and sifted through his Sunday pages, found a more recent original Sunday India ink page, and signed it this time for Alice [Mrs. Maltin] and me, and signed it “Sparky”, which was his nickname with his friends. So sometimes luck and timing and coincidence play a role in all of this.

C.B.-W.: And it’s probably a really good letter, right?

L.M.: I guess I wrote pretty good letters. I’ve seen a few and they embarrass me now. Like the time I wrote to [film historian] William K. Everson, having just recently met him, telling him I thought Metropolis was boring. I’m not reprinting that anywhere.

* * *

[Scott spoke about the principles that motivated him when he embarked on his own writing career…]:

S.E.: I knew what I didn’t want to do more than I did what I wanted to do. I wanted to start writing and interviewing people; I think Kevin Brownlow’s The Parade’s Gone By was a huge influence on me — a whole generation of historians, actually — and I knew what I didn’t want to do, because I was starting to read seriously, read books about writers, read books about artists, and all these other things. And then I’d read books about movie people and they were on such a superficial, trashy level. And I didn’t see any reason why a book about a movie director or an actor should be written on such a mediocre level when you wouldn’t think of writing a book about an author like that. So I was kind of coming around to the idea of writing serious books about people that usually weren’t treated seriously. The first person I interviewed outside of Cleveland — I mean, Andy McLaglen came through to push a movie, or Earl Holliman would come through to push a movie, so I would talk to them — but the first person I interviewed in Los Angeles was John Wayne, and it’s been downhill ever since. I mean, if that’s your first out of the box when you’re 21 years old, why should you be worried about talking to anybody else on the face of the earth, including the Pope?

S.E.: I knew what I didn’t want to do more than I did what I wanted to do. I wanted to start writing and interviewing people; I think Kevin Brownlow’s The Parade’s Gone By was a huge influence on me — a whole generation of historians, actually — and I knew what I didn’t want to do, because I was starting to read seriously, read books about writers, read books about artists, and all these other things. And then I’d read books about movie people and they were on such a superficial, trashy level. And I didn’t see any reason why a book about a movie director or an actor should be written on such a mediocre level when you wouldn’t think of writing a book about an author like that. So I was kind of coming around to the idea of writing serious books about people that usually weren’t treated seriously. The first person I interviewed outside of Cleveland — I mean, Andy McLaglen came through to push a movie, or Earl Holliman would come through to push a movie, so I would talk to them — but the first person I interviewed in Los Angeles was John Wayne, and it’s been downhill ever since. I mean, if that’s your first out of the box when you’re 21 years old, why should you be worried about talking to anybody else on the face of the earth, including the Pope?

[…and about approaching future projects as he ages]:

Who knows? At some point you pitch face-forward. Now, of course David McCullough’s 85 years old and he’s still working. That’s great, he’s lucky, he’s got good genes. But you’re not guaranteed that. When I was 35 or even 40, somebody would suggest something, I’d say, “That sounds like fun, I’ve never read that book. Sure, I’ll do it.” Now, I circle and circle and circle, is this worth those years of my life I have remaining, three or four years that I have remaining? Is this guy, is this woman worth the time? It’s an entirely different transaction now than it was.

L.M.: As a reader, I’m going to interject to say “Yes.” Because Scott’s book on John Wayne is the best book on John Wayne, just as his book on Cecil B. DeMille is the definitive book on Cecil B. DeMille. I’m compulsive, but I’ve been tempted to actually discard some of my other books because they’re taking up shelf space.

C.B.-W.: That’s a great compliment.

L.M.: Well, I mean it to be a great compliment, but it’s also the truth. I’m too anal, I can’t get rid of the other books, but if I could tame my instincts I would just say, “These are useless now ’cause Scott’s done the ultimate job.”

C.B.-W.: Scott, that’s funny that you mention David McCullough because I remember hearing an interview with him on NPR where he said the major reason he wrote the book on Harry Truman was because he had been writing a book, or planning to write a book, on Pablo Picasso, and he was such a dreadful human being he couldn’t imagine spending time writing about a dreadful human being. So he said, “I’m gonna write about somebody I like, somebody that’s a nice guy.” So that obviously figures into you as well.

L.M.: You know that old saying, “No man is a hero to his valet.” I’ve heard biographers say that, in a different context, that when they get to really know their subject well, they become disillusioned. I guess that’s just part of the game.

S.E.: Sometimes, sometimes not. People ask me, “What was the book you loved writing the most?” and I always tell them the Lubitsch book, my book on Lubitsch [Ernst Lubitsch: Laughter in Paradise]. Because he was such a fully actualized person, what a shrink would call actualized. He was exactly the person he wanted to be, and he made exactly the films he wanted to make. Nobody got in his way, and nothing got in his way, until his heart broke down. But he was very — he loved being him. And the most difficult book, conversely, was John Ford [Print the Legend: The Life and Times of John Ford]. Because it was like being locked in a telephone booth with twelve Eugene O’Neill characters, and they’re all mean, and they’re all snarling at each other, and they’re all stinking drunk. I had to keep watching the movies to remind myself why I was writing the book. You get over any kind of romantic ideal that talent cares who it happens to. Talent doesn’t care who it happens to. Some people are great stewards of their talent and other people spend it like they’re drunken sailors. Ford was not a particularly pleasant human being, but he was a stupendous artist, a stupendous American artist, and I had to keep watching the movies to remind myself why I was doing the book.

So this is a long, involved way to answer your question. No, I don’t have to love my subject. But I have to respect them as artists. That’s mandatory. That’s mandatory. Now there are people that will spend fifteen years writing a two-volume biography of Josef Goebbels. I am not one of those people. I might read those books, but I have zero interest in spending time with a human beast. There has to be something there to validate that human being in my eyes. It can be their life, it can be their work — hopefully it’s both, but it has to be something.

* * *

That’s as much as I was able to record of this productive and stimulating conversation. I wish there was more, but I think that will give you an idea of what a good time was had by all that afternoon. I also remember that in a Q&A with the audience in the second half of the session, someone asked if there were any highly-regarded films that the two men consider overrated, and that Leonard Maltin cited A Place in the Sun (1951) as one that he doesn’t think has aged well. Sorry, I don’t recall which movie(s) Scott Eyman may have mentioned. If anyone reading this happens to have been there in the Cinevent screening room that day, I welcome your memories and reflections in the comments. In the meantime, I’ll move on to the fourth and last day of the weekend.

That’s as much as I was able to record of this productive and stimulating conversation. I wish there was more, but I think that will give you an idea of what a good time was had by all that afternoon. I also remember that in a Q&A with the audience in the second half of the session, someone asked if there were any highly-regarded films that the two men consider overrated, and that Leonard Maltin cited A Place in the Sun (1951) as one that he doesn’t think has aged well. Sorry, I don’t recall which movie(s) Scott Eyman may have mentioned. If anyone reading this happens to have been there in the Cinevent screening room that day, I welcome your memories and reflections in the comments. In the meantime, I’ll move on to the fourth and last day of the weekend.

To be concluded…

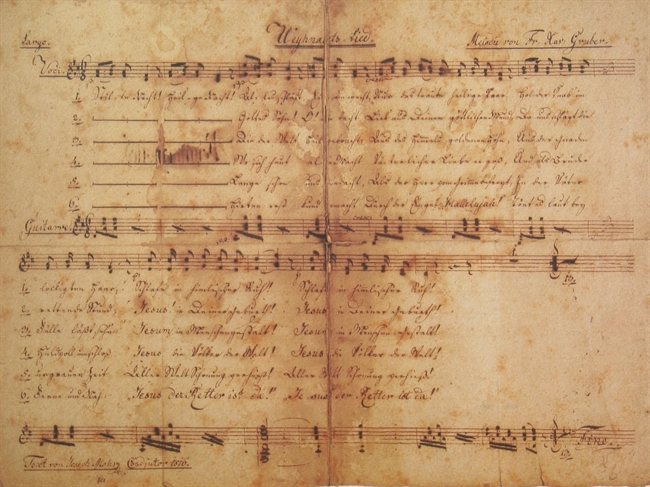

I know this is a departure from the subject of movies and the Golden Age of Hollywood, but as the Christmas Season rolls around once again, I don’t want it to go unobserved that 2018 marks the Bicentennial of the most familiar and beloved of all Christmas carols: “Silent Night”.

I know this is a departure from the subject of movies and the Golden Age of Hollywood, but as the Christmas Season rolls around once again, I don’t want it to go unobserved that 2018 marks the Bicentennial of the most familiar and beloved of all Christmas carols: “Silent Night”.

The last day of Cinevent 50 began with Kitty (1945), starring Paulette Goddard and Ray Milland. Since I wrote the program notes for Kitty, I’m going to follow my practice of years past and reproduce those notes here. However, I should mention that my notes for Cinevent were adapted from my 2013 Cinedrome post on this, one of my favorite pictures. So you’ve got a choice: you can read on now, or if you want the full gamut of what I had to say back then, you can click

The last day of Cinevent 50 began with Kitty (1945), starring Paulette Goddard and Ray Milland. Since I wrote the program notes for Kitty, I’m going to follow my practice of years past and reproduce those notes here. However, I should mention that my notes for Cinevent were adapted from my 2013 Cinedrome post on this, one of my favorite pictures. So you’ve got a choice: you can read on now, or if you want the full gamut of what I had to say back then, you can click  Actually, not all of Kitty made it to the screen. Marshall’s novel was a pretty steamy bodice-ripper by 1940s standards, the tale of a 14-year-old London prostitute blithely sleeping her way up the social ladder in the days of King George III. Kitty (she doesn’t have a last name) gets caught stealing the shoes of the painter Thomas Gainsborough — and he, liking the look of her, invites her into his studio to pose. There, Kitty catches the eye of a ne’er-do-well visitor, Sir Hugh Marcy, who takes her home with him and introduces her to the pleasures of orgasmic sex. Sir Hugh and his gin-sodden aunt Lady Susan take Kitty under their wings, passing her off as the orphaned child of a dear friend and subjecting her to a crash course in proper speech and manners. Kitty blooms under their tutelage and her lovers multiply.

Actually, not all of Kitty made it to the screen. Marshall’s novel was a pretty steamy bodice-ripper by 1940s standards, the tale of a 14-year-old London prostitute blithely sleeping her way up the social ladder in the days of King George III. Kitty (she doesn’t have a last name) gets caught stealing the shoes of the painter Thomas Gainsborough — and he, liking the look of her, invites her into his studio to pose. There, Kitty catches the eye of a ne’er-do-well visitor, Sir Hugh Marcy, who takes her home with him and introduces her to the pleasures of orgasmic sex. Sir Hugh and his gin-sodden aunt Lady Susan take Kitty under their wings, passing her off as the orphaned child of a dear friend and subjecting her to a crash course in proper speech and manners. Kitty blooms under their tutelage and her lovers multiply. David Chierichetti’s 1995 book Mitchell Leisen: Hollywood Director does much to correct this injustice to Leisen, but its information on Kitty is sketchy and unreliable — when it’s not downright false. Chierichetti says it’s set in “Restoration Era England” when it takes place 125 years later. Leisen himself, interviewed, says: “I spent two years researching Gainsborough and the way he painted. We determined that the picture took place in 1659, and there’s nothing in the picture that was painted by him after that year.” Wrong again. Gainsborough wasn’t even born until 1727, and an opening title card explicitly sets the story in 1783. Clearly, Leisen (who died in 1972) had not seen the picture recently when he discussed it with Chierichetti, nor had Chierichetti when he wrote about it. And Leisen never spent two years in research. Kitty was ready for release by the end of 1944 but was held up a full year by Paramount’s backlog of product; two years of research would have had Leisen beginning in 1942, a year before the novel was published.

David Chierichetti’s 1995 book Mitchell Leisen: Hollywood Director does much to correct this injustice to Leisen, but its information on Kitty is sketchy and unreliable — when it’s not downright false. Chierichetti says it’s set in “Restoration Era England” when it takes place 125 years later. Leisen himself, interviewed, says: “I spent two years researching Gainsborough and the way he painted. We determined that the picture took place in 1659, and there’s nothing in the picture that was painted by him after that year.” Wrong again. Gainsborough wasn’t even born until 1727, and an opening title card explicitly sets the story in 1783. Clearly, Leisen (who died in 1972) had not seen the picture recently when he discussed it with Chierichetti, nor had Chierichetti when he wrote about it. And Leisen never spent two years in research. Kitty was ready for release by the end of 1944 but was held up a full year by Paramount’s backlog of product; two years of research would have had Leisen beginning in 1942, a year before the novel was published. After lunch we got the last three chapters of The Masked Marvel, and we finally learned who the Masked Marvel really was (as if it mattered; I never could keep the candidates straight — I can’t even remember which one wound up dying in that L.A. beanfield).

After lunch we got the last three chapters of The Masked Marvel, and we finally learned who the Masked Marvel really was (as if it mattered; I never could keep the candidates straight — I can’t even remember which one wound up dying in that L.A. beanfield). Beauty for Sale was nicely done, and the print was handsome, but it was overshadowed by the picture that followed it, which in its turn closed out the weekend with one last highlight. This was Dreamboat (1952), a marvelous spoof of Hollywood, television, and academia that probably represents the pinnacle of writer/director Claude Binyon’s career.

Beauty for Sale was nicely done, and the print was handsome, but it was overshadowed by the picture that followed it, which in its turn closed out the weekend with one last highlight. This was Dreamboat (1952), a marvelous spoof of Hollywood, television, and academia that probably represents the pinnacle of writer/director Claude Binyon’s career. Binyon occasionally directed his own scripts, and with Dreamboat he was at the top of both games. Clifton Webb played Thornton Sayre, a stuffy, acerbic college professor whose students call him “Old Ironheart” behind his back. The advent of television has uncovered a secret long buried in his past: He used to be a silent-screen heartthrob known as Bruce Blair (imagine a combination of Douglas Fairbanks and John Gilbert), and now those obsolete relics of a bygone day are turning up on TV, hosted by his former co-star Gloria Marlowe (Ginger Rogers). The movies have created a sensation, upsetting the stuffy trustees of his college, so he strikes out for New York to get an injunction to stop this invasion of his privacy, taking along his daughter Carol (Anne Francis), who is well on her way to becoming the same kind of stick-in-the-mud killjoy that he is. While Gloria and her TV producer (Fred Clark) try to charm Prof. Sayre out of his dudgeon, Carol is squired around town by the producer’s assistant (Jeffrey Hunter). In the process, father learns that reversing the wheels of showbiz is easier said than done, while daughter learns there’s more to having a good time than working on a thesis to “challenge the existence of Homer as an individual.” Dreamboat was a witty delight every inch of the way, poking fun at show business and academia with both barrels and scoring a bullseye every time. It was also a testament to 20th Century Fox’s ongoing ingenuity in finding vehicles to showcase the unorthodox but inimitable talents of Clifton Webb. Those of use who stayed through to the end of the weekend were well-rewarded for our loyalty.

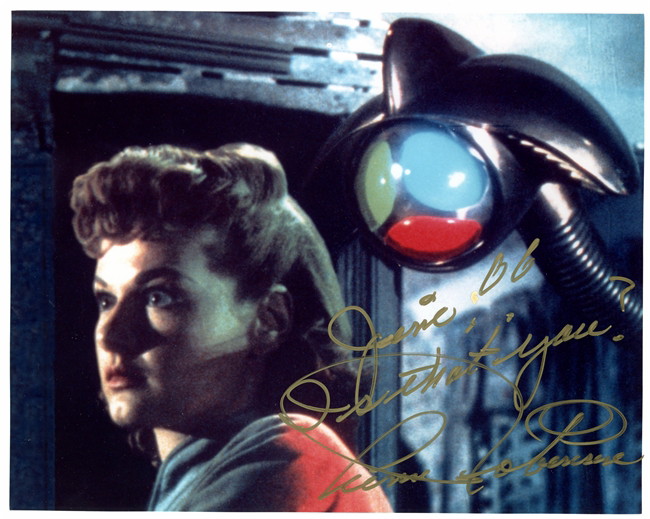

Binyon occasionally directed his own scripts, and with Dreamboat he was at the top of both games. Clifton Webb played Thornton Sayre, a stuffy, acerbic college professor whose students call him “Old Ironheart” behind his back. The advent of television has uncovered a secret long buried in his past: He used to be a silent-screen heartthrob known as Bruce Blair (imagine a combination of Douglas Fairbanks and John Gilbert), and now those obsolete relics of a bygone day are turning up on TV, hosted by his former co-star Gloria Marlowe (Ginger Rogers). The movies have created a sensation, upsetting the stuffy trustees of his college, so he strikes out for New York to get an injunction to stop this invasion of his privacy, taking along his daughter Carol (Anne Francis), who is well on her way to becoming the same kind of stick-in-the-mud killjoy that he is. While Gloria and her TV producer (Fred Clark) try to charm Prof. Sayre out of his dudgeon, Carol is squired around town by the producer’s assistant (Jeffrey Hunter). In the process, father learns that reversing the wheels of showbiz is easier said than done, while daughter learns there’s more to having a good time than working on a thesis to “challenge the existence of Homer as an individual.” Dreamboat was a witty delight every inch of the way, poking fun at show business and academia with both barrels and scoring a bullseye every time. It was also a testament to 20th Century Fox’s ongoing ingenuity in finding vehicles to showcase the unorthodox but inimitable talents of Clifton Webb. Those of use who stayed through to the end of the weekend were well-rewarded for our loyalty. Now I’d like to say a few words about Anne Francis. As Dreamboat romps across the screen, her Carol Sayre transforms from a buzzkill bookworm who looks about five days past puberty into something like the Anne Francis we all remember. She had a long and worthy career, with 169 credits between 1947 and 2004; she was always a welcome presence, and I’d venture to guess everyone who ever saw her in a movie or on TV remembered her fondly. Yet she never quite became a real star; I doubt if she ever got her name above a title, and she got top billing only in her one-season TV series Honey West. I wonder why?

Now I’d like to say a few words about Anne Francis. As Dreamboat romps across the screen, her Carol Sayre transforms from a buzzkill bookworm who looks about five days past puberty into something like the Anne Francis we all remember. She had a long and worthy career, with 169 credits between 1947 and 2004; she was always a welcome presence, and I’d venture to guess everyone who ever saw her in a movie or on TV remembered her fondly. Yet she never quite became a real star; I doubt if she ever got her name above a title, and she got top billing only in her one-season TV series Honey West. I wonder why? Apologies for the delay, Cinedrome readers. I’ve been on vacation, but now I’m back and ready to resume my recap of this year’s Cinevent.

Apologies for the delay, Cinedrome readers. I’ve been on vacation, but now I’m back and ready to resume my recap of this year’s Cinevent. After dinner it was The Sea Spoilers (1936), one of the B-pictures John Wayne made at Universal in an effort to break out of the horse-opera ghetto he was mired in at Republic and for fly-by-night producer Paul Malvern. Two years ago Cinevent presented probably the best of these, California Straight Ahead, but all of them were pretty good. Sea Spoilers had the Duke as a U.S. Coast Guard officer on the trail of seal poachers led by Russell Hicks, with his sweetheart Nan Gray caught in the crossfire.

After dinner it was The Sea Spoilers (1936), one of the B-pictures John Wayne made at Universal in an effort to break out of the horse-opera ghetto he was mired in at Republic and for fly-by-night producer Paul Malvern. Two years ago Cinevent presented probably the best of these, California Straight Ahead, but all of them were pretty good. Sea Spoilers had the Duke as a U.S. Coast Guard officer on the trail of seal poachers led by Russell Hicks, with his sweetheart Nan Gray caught in the crossfire. Next was, for many of those in attendance, the highlight of the whole weekend: 1946’s Three Little Girls in Blue. (Personally, I’d put it neck-and-neck with The War of the Worlds, but that could just be me.) As I’ve mentioned before, this was 20th Century Fox’s second remake of their own Three Blind Mice from 1938 (the first remake, in 1941, was the Betty Grable vehicle Moon Over Miami), about three sisters living high on a modest inheritance, hoping to land rich husbands before the money runs out. It’s a movie of immense charm and constant pleasures that deserves to be better known.

Next was, for many of those in attendance, the highlight of the whole weekend: 1946’s Three Little Girls in Blue. (Personally, I’d put it neck-and-neck with The War of the Worlds, but that could just be me.) As I’ve mentioned before, this was 20th Century Fox’s second remake of their own Three Blind Mice from 1938 (the first remake, in 1941, was the Betty Grable vehicle Moon Over Miami), about three sisters living high on a modest inheritance, hoping to land rich husbands before the money runs out. It’s a movie of immense charm and constant pleasures that deserves to be better known. L.M.: I think it was the fact that when I was growing up in the ’50s and ’60s, television was a living museum of movies. And being a Baby Boomer, I became a TV addict, and at that time — I’m not telling you guys anything you don’t know; if there were younger people here I’d have to explain it a little more fully — but I watched Laurel and Hardy every day, every day of my life growing up. The Little Rascals, every day. Walt Disney every week. At one golden period, The Mickey Mouse Club every afternoon. All of these things left a deep, deep impression on me, and they’re still the things I care about most today. So I think it all began there.

L.M.: I think it was the fact that when I was growing up in the ’50s and ’60s, television was a living museum of movies. And being a Baby Boomer, I became a TV addict, and at that time — I’m not telling you guys anything you don’t know; if there were younger people here I’d have to explain it a little more fully — but I watched Laurel and Hardy every day, every day of my life growing up. The Little Rascals, every day. Walt Disney every week. At one golden period, The Mickey Mouse Club every afternoon. All of these things left a deep, deep impression on me, and they’re still the things I care about most today. So I think it all began there. C.B.-W.: Scott, I know this convention, this festival in particular had a big part of your upbringing, didn’t it?

C.B.-W.: Scott, I know this convention, this festival in particular had a big part of your upbringing, didn’t it? L.M.: Actually, I started writing letters, that’s where it began. I wrote fan letters; I was big on that. I got some wonderful, wonderful answers. My first ambition had been to be a cartoonist, and I wrote to some of my heroes. I wanted to be a cartoonist and I sent some of my samples to Charles Schulz, who wrote back the kindest, most encouraging letter, very supportive. A personal letter, not a form letter, just a wonderful gesture on his part. And he included in the package an original signed daily Peanuts strip. Unsolicited. P.S., 30 years later I got hired by United Media, his syndicator, to interview him in his studio in Santa Rosa, Calif., for a video that was going to accompany a traveling museum tour. So as they’re getting the cameras set I told him that story. He jumped out of his seat, he says, “We gotta get you something newer!” He went over to one of his work tables and sifted through his Sunday pages, found a more recent original Sunday India ink page, and signed it this time for Alice [Mrs. Maltin] and me, and signed it “Sparky”, which was his nickname with his friends. So sometimes luck and timing and coincidence play a role in all of this.

L.M.: Actually, I started writing letters, that’s where it began. I wrote fan letters; I was big on that. I got some wonderful, wonderful answers. My first ambition had been to be a cartoonist, and I wrote to some of my heroes. I wanted to be a cartoonist and I sent some of my samples to Charles Schulz, who wrote back the kindest, most encouraging letter, very supportive. A personal letter, not a form letter, just a wonderful gesture on his part. And he included in the package an original signed daily Peanuts strip. Unsolicited. P.S., 30 years later I got hired by United Media, his syndicator, to interview him in his studio in Santa Rosa, Calif., for a video that was going to accompany a traveling museum tour. So as they’re getting the cameras set I told him that story. He jumped out of his seat, he says, “We gotta get you something newer!” He went over to one of his work tables and sifted through his Sunday pages, found a more recent original Sunday India ink page, and signed it this time for Alice [Mrs. Maltin] and me, and signed it “Sparky”, which was his nickname with his friends. So sometimes luck and timing and coincidence play a role in all of this. S.E.: I knew what I didn’t want to do more than I did what I wanted to do. I wanted to start writing and interviewing people; I think Kevin Brownlow’s The Parade’s Gone By was a huge influence on me — a whole generation of historians, actually — and I knew what I didn’t want to do, because I was starting to read seriously, read books about writers, read books about artists, and all these other things. And then I’d read books about movie people and they were on such a superficial, trashy level. And I didn’t see any reason why a book about a movie director or an actor should be written on such a mediocre level when you wouldn’t think of writing a book about an author like that. So I was kind of coming around to the idea of writing serious books about people that usually weren’t treated seriously. The first person I interviewed outside of Cleveland — I mean, Andy McLaglen came through to push a movie, or Earl Holliman would come through to push a movie, so I would talk to them — but the first person I interviewed in Los Angeles was John Wayne, and it’s been downhill ever since. I mean, if that’s your first out of the box when you’re 21 years old, why should you be worried about talking to anybody else on the face of the earth, including the Pope?

S.E.: I knew what I didn’t want to do more than I did what I wanted to do. I wanted to start writing and interviewing people; I think Kevin Brownlow’s The Parade’s Gone By was a huge influence on me — a whole generation of historians, actually — and I knew what I didn’t want to do, because I was starting to read seriously, read books about writers, read books about artists, and all these other things. And then I’d read books about movie people and they were on such a superficial, trashy level. And I didn’t see any reason why a book about a movie director or an actor should be written on such a mediocre level when you wouldn’t think of writing a book about an author like that. So I was kind of coming around to the idea of writing serious books about people that usually weren’t treated seriously. The first person I interviewed outside of Cleveland — I mean, Andy McLaglen came through to push a movie, or Earl Holliman would come through to push a movie, so I would talk to them — but the first person I interviewed in Los Angeles was John Wayne, and it’s been downhill ever since. I mean, if that’s your first out of the box when you’re 21 years old, why should you be worried about talking to anybody else on the face of the earth, including the Pope? That’s as much as I was able to record of this productive and stimulating conversation. I wish there was more, but I think that will give you an idea of what a good time was had by all that afternoon. I also remember that in a Q&A with the audience in the second half of the session, someone asked if there were any highly-regarded films that the two men consider overrated, and that Leonard Maltin cited A Place in the Sun (1951) as one that he doesn’t think has aged well. Sorry, I don’t recall which movie(s) Scott Eyman may have mentioned. If anyone reading this happens to have been there in the Cinevent screening room that day, I welcome your memories and reflections in the comments. In the meantime, I’ll move on to the fourth and last day of the weekend.

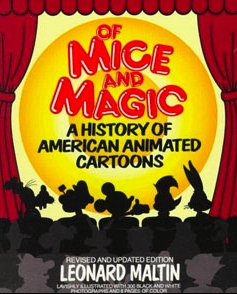

That’s as much as I was able to record of this productive and stimulating conversation. I wish there was more, but I think that will give you an idea of what a good time was had by all that afternoon. I also remember that in a Q&A with the audience in the second half of the session, someone asked if there were any highly-regarded films that the two men consider overrated, and that Leonard Maltin cited A Place in the Sun (1951) as one that he doesn’t think has aged well. Sorry, I don’t recall which movie(s) Scott Eyman may have mentioned. If anyone reading this happens to have been there in the Cinevent screening room that day, I welcome your memories and reflections in the comments. In the meantime, I’ll move on to the fourth and last day of the weekend. Saturday morning is always cartoon time at Cinevent. This year, in deference to the presence of Leonard Maltin, animation curator Stewart McKissick selected the program based on comments in Maltin’s seminal book

Saturday morning is always cartoon time at Cinevent. This year, in deference to the presence of Leonard Maltin, animation curator Stewart McKissick selected the program based on comments in Maltin’s seminal book  After the cartoons — and Chapters 7 to 9 of The Masked Marvel — the first feature of the day was The Eyes of Julia Deep (1918), one of the few surviving films of Mary Miles Minter. Over 80 percent of the 54 pictures she made between 1912 and 1923 are considered lost — which, in a way, is emblematic of the cloud this woman lived under for pretty much her whole life. I dealt with poor Mary in some detail in

After the cartoons — and Chapters 7 to 9 of The Masked Marvel — the first feature of the day was The Eyes of Julia Deep (1918), one of the few surviving films of Mary Miles Minter. Over 80 percent of the 54 pictures she made between 1912 and 1923 are considered lost — which, in a way, is emblematic of the cloud this woman lived under for pretty much her whole life. I dealt with poor Mary in some detail in

Day 2 of Cinevent began bright and early with what was probably the most…the most…well, just about the oddest movie of the whole weekend: Night in Paradise (1946). Produced by Walter Wanger for Universal, it was based on George S. Hellman’s novel Peacock’s Feather, and Wanger had been trying to get it produced ever since snapping up the film rights shortly after the book was published in 1931. For a while, according to Richard Barrios’s program notes, he planned to star Ann Harding and Charles Boyer, and to make it the first feature in three-strip Technicolor. For one reason or another, he lost the services of Ann Harding, which — for the time being — sank the whole project (and instead, Becky Sharp became the first full-Technicolor feature in 1935; Wanger ventured into Tech the following year when he produced The Trail of the Lonesome Pine at Paramount).

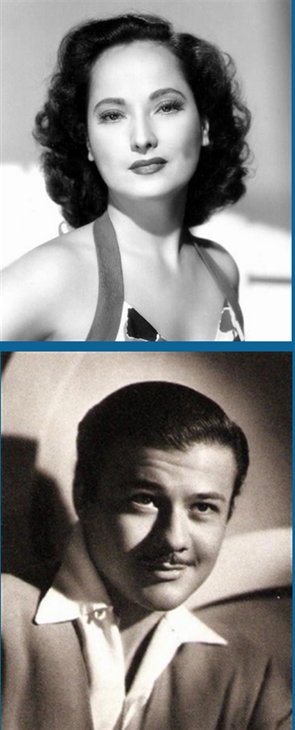

Day 2 of Cinevent began bright and early with what was probably the most…the most…well, just about the oddest movie of the whole weekend: Night in Paradise (1946). Produced by Walter Wanger for Universal, it was based on George S. Hellman’s novel Peacock’s Feather, and Wanger had been trying to get it produced ever since snapping up the film rights shortly after the book was published in 1931. For a while, according to Richard Barrios’s program notes, he planned to star Ann Harding and Charles Boyer, and to make it the first feature in three-strip Technicolor. For one reason or another, he lost the services of Ann Harding, which — for the time being — sank the whole project (and instead, Becky Sharp became the first full-Technicolor feature in 1935; Wanger ventured into Tech the following year when he produced The Trail of the Lonesome Pine at Paramount). In place of Montez and Hall, Wanger cast Merle Oberon (left above) and Montez’s frequent co-star Turhan Bey (below). Casting Oberon was definitely a step up from Maria Montez. Turhan Bey was more like a step across. Born Turhan Sahultavy in Vienna to a Turkish Muslim father and a Czechoslovakian Jewish mother, he and his divorced mom fled Austria when Hitler annexed the country, and they wound up in Los Angeles in 1940, when Turhan was 18. When so many of Hollywood’s leading men marched off to World War II, Bey was one of the stay-at-homes who benefited from the manpower shortage. He was a handsome young devil and really not a bad actor, but he somehow managed to be both exotic and bland at the same time. He had the kind of foreign accent that came of speaking English too precisely, and the blandness made him unthreatening; it was a combination that stood him in good stead for the duration of the war.

In place of Montez and Hall, Wanger cast Merle Oberon (left above) and Montez’s frequent co-star Turhan Bey (below). Casting Oberon was definitely a step up from Maria Montez. Turhan Bey was more like a step across. Born Turhan Sahultavy in Vienna to a Turkish Muslim father and a Czechoslovakian Jewish mother, he and his divorced mom fled Austria when Hitler annexed the country, and they wound up in Los Angeles in 1940, when Turhan was 18. When so many of Hollywood’s leading men marched off to World War II, Bey was one of the stay-at-homes who benefited from the manpower shortage. He was a handsome young devil and really not a bad actor, but he somehow managed to be both exotic and bland at the same time. He had the kind of foreign accent that came of speaking English too precisely, and the blandness made him unthreatening; it was a combination that stood him in good stead for the duration of the war. A more satisfying western was the 1920 William S. Hart silent The Toll Gate. Hart plays Black Deering, a semi-reformed outlaw on the run who takes refuge with an abandoned frontier wife (Anna Q. Nilsson) and her toddler son (“Master” Richard Headrick). He bonds with them so quickly that when a posse shows up on his trail (fortuitously not knowing what he looks like), she doesn’t hesitate to claim he’s her husband. Actually, it turns out that the husband who ran out on her is none other than the former member of Deering’s gang who ratted him out to the law. Director Lambert Hillyer’s scenario thus establishes the perfect set-up for a double dose of revenge before Deering settles down and makes his reformation complete, Nilsson’s Mary Brown having made an honest man of him. The picture had Hart’s trademark dusty realism, and his interplay with Nilsson and young Headrick had the unpretentious ring of truth. This Headrick kid especially, only three at the time, was a real charmer. He had a busy few years in Hollywood, but his screen career was over by the time he was nine. Still, he lived into the 21st century, dying at 84 in November 2001. “Nobody ever talked to him?” Scott Eyman wondered. Evidently not, and that’s a pity.

A more satisfying western was the 1920 William S. Hart silent The Toll Gate. Hart plays Black Deering, a semi-reformed outlaw on the run who takes refuge with an abandoned frontier wife (Anna Q. Nilsson) and her toddler son (“Master” Richard Headrick). He bonds with them so quickly that when a posse shows up on his trail (fortuitously not knowing what he looks like), she doesn’t hesitate to claim he’s her husband. Actually, it turns out that the husband who ran out on her is none other than the former member of Deering’s gang who ratted him out to the law. Director Lambert Hillyer’s scenario thus establishes the perfect set-up for a double dose of revenge before Deering settles down and makes his reformation complete, Nilsson’s Mary Brown having made an honest man of him. The picture had Hart’s trademark dusty realism, and his interplay with Nilsson and young Headrick had the unpretentious ring of truth. This Headrick kid especially, only three at the time, was a real charmer. He had a busy few years in Hollywood, but his screen career was over by the time he was nine. Still, he lived into the 21st century, dying at 84 in November 2001. “Nobody ever talked to him?” Scott Eyman wondered. Evidently not, and that’s a pity. Richard Barrios did introductory honors again for The Phantom President (1932), one of the most historic musicals Hollywood ever turned out. It’s historic not because it’s one of the great film musicals (it’s pretty good but not great), but because it gives us a permanent record of George M. Cohan, the legendary force of showbiz nature who virtually single-handedly invented the American musical comedy. Personally, he was an arrogant megalomaniac who made Al Jolson look timorous; he made life hell for everybody on the set, especially those whose jobs he thought he could do better — director Norman Taurog, composer Richard Rodgers, lyricist Lorenz Hart — and he bad-mouthed the picture far and wide after it went into release. It was churlish of him; he never realized the inestimable service The Phantom President did to his legend, giving future generations something to go on besides yellowing press clippings and the dwindling memories of those who saw his performances in person.

Richard Barrios did introductory honors again for The Phantom President (1932), one of the most historic musicals Hollywood ever turned out. It’s historic not because it’s one of the great film musicals (it’s pretty good but not great), but because it gives us a permanent record of George M. Cohan, the legendary force of showbiz nature who virtually single-handedly invented the American musical comedy. Personally, he was an arrogant megalomaniac who made Al Jolson look timorous; he made life hell for everybody on the set, especially those whose jobs he thought he could do better — director Norman Taurog, composer Richard Rodgers, lyricist Lorenz Hart — and he bad-mouthed the picture far and wide after it went into release. It was churlish of him; he never realized the inestimable service The Phantom President did to his legend, giving future generations something to go on besides yellowing press clippings and the dwindling memories of those who saw his performances in person. The rest of Day 2 we can cover in a few paragraphs. C.B. DeMille’s Don’t Change Your Husband (1919) presented Gloria Swanson at her sleek-and-smartest as a neglected wife tempted away from her lumpen husband (Elliott Dexter) by a smooth-talking roué (Lew Cody), only to learn that the grass isn’t always greener.

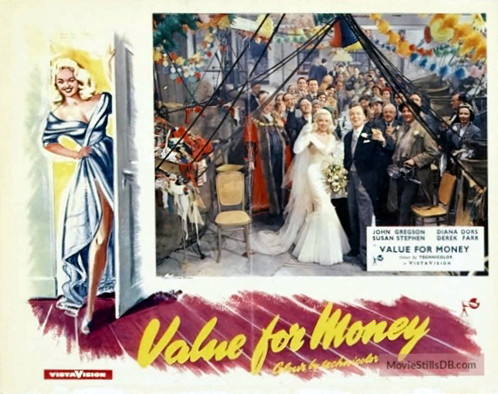

The rest of Day 2 we can cover in a few paragraphs. C.B. DeMille’s Don’t Change Your Husband (1919) presented Gloria Swanson at her sleek-and-smartest as a neglected wife tempted away from her lumpen husband (Elliott Dexter) by a smooth-talking roué (Lew Cody), only to learn that the grass isn’t always greener. Finally there was Value for Money, a rather sour British comedy from 1955, about a tight-fisted Yorkshireman (John Gregson) who gets involved with a gold-digging London showgirl (Diana Dors), to the wounded dismay of local newspaper reporter Susan Stephen, who (unaccountably) loves him. The picture had excellent Technicolor photography by Geoffrey Unsworth (and Cinevent’s print did it full justice), and Diana Dors showed herself to be not just a luscious eyeful but a comic actress of wit and charm. Still, the movie was a sour misfire, mainly because of John Gregson’s character — a clueless, mean-spirited boor who in the end gets much better than is coming to him. Somebody like Alec Guinness or Peter Sellers might have managed to make this unpleasant pill eccentrically endearing, but the worthy Gregson wasn’t that kind of actor. Value for Money has its moments of visual and verbal wit, but it’s weighed down by a flinty, unsympathetic center.

Finally there was Value for Money, a rather sour British comedy from 1955, about a tight-fisted Yorkshireman (John Gregson) who gets involved with a gold-digging London showgirl (Diana Dors), to the wounded dismay of local newspaper reporter Susan Stephen, who (unaccountably) loves him. The picture had excellent Technicolor photography by Geoffrey Unsworth (and Cinevent’s print did it full justice), and Diana Dors showed herself to be not just a luscious eyeful but a comic actress of wit and charm. Still, the movie was a sour misfire, mainly because of John Gregson’s character — a clueless, mean-spirited boor who in the end gets much better than is coming to him. Somebody like Alec Guinness or Peter Sellers might have managed to make this unpleasant pill eccentrically endearing, but the worthy Gregson wasn’t that kind of actor. Value for Money has its moments of visual and verbal wit, but it’s weighed down by a flinty, unsympathetic center.