Every now and then in the 1930s (and more often than you might think) the Hollywood factory would turn out a picture that just didn’t fit the mold, one that seems in retrospect out of step with the reigning star system, the house style of its studio, the temper of the times — or a combination of all three. Lewis Milestone’s The General Died at Dawn was like that, and Warner Bros.’ Victorian-ornate A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and 1934’s Death Takes a Holiday. (For that matter, so was King Kong.) “Miracle pictures,” I call them; the fact that they’re as good as they are — that they were made at all — seems almost to violate the laws of Hollywood physics.

Every now and then in the 1930s (and more often than you might think) the Hollywood factory would turn out a picture that just didn’t fit the mold, one that seems in retrospect out of step with the reigning star system, the house style of its studio, the temper of the times — or a combination of all three. Lewis Milestone’s The General Died at Dawn was like that, and Warner Bros.’ Victorian-ornate A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and 1934’s Death Takes a Holiday. (For that matter, so was King Kong.) “Miracle pictures,” I call them; the fact that they’re as good as they are — that they were made at all — seems almost to violate the laws of Hollywood physics.

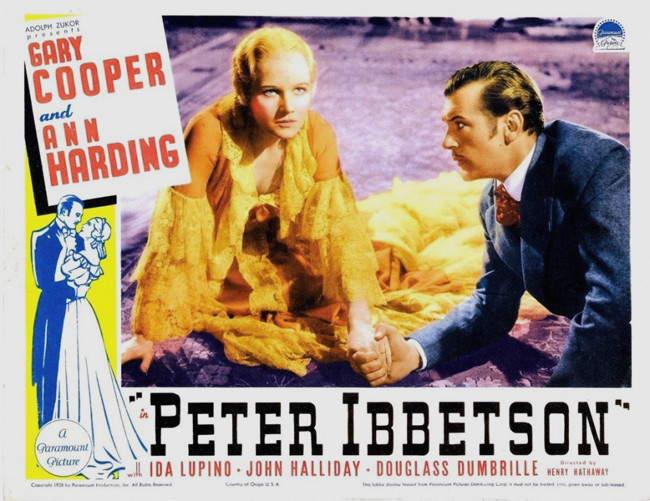

In 1935, fresh off the roaring success of his first A-picture, The Lives of a Bengal Lancer, Henry Hathaway turned out one of these miracle pictures for Paramount. Peter Ibbetson is unlike any other movie Hathaway ever made. It’s unlike any other movie its star, Gary Cooper, ever made. Until the 1940s, when the trauma of World War II spawned a sub-genre of movies concerned with immortality and the afterlife (Here Comes Mr. Jordan, Heaven Can Wait, A Guy Named Joe, The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, etc.), it was almost unique. It’s impossible to dismiss Peter Ibbetson once you’ve seen it. This post has been delayed because I want to be very careful what I write about it, to get what I want to say exactly right. And also because, revisiting Hathaway’s haunting, lyrical movie, I can’t restrain myself from wanting to watch it over and over — sometimes straight through, sometimes hopping from one favorite moment to another.

If Peter Ibbetson seemed strange to audiences in 1935, it probably wasn’t because it was so spiritual or ethereal, but because it was so old-fashioned. It must have looked like something D.W. Griffith would have done in his heyday (in fact, looking back now, it seems odd that Griffith never did). The story originated in an 1891 novel by George du Maurier, grandfather of Daphne du Maurier. The strain of gothic romance that runs through Dame Daphne’s novels (Rebecca, Jamaica Inn) can be traced to her grandfather, even though he’d been dead over a decade when she was born. Peter Ibbetson, riding the wave of spiritualism and occultism that was cresting in the late Victorian Era, was a modest success, and du Maurier followed it in 1894 with the hugely successful Trilby (in which he contributed the term “Svengali” to the English language).

In the late 1910s playwright John Nathaniel Raphael and actress-director Constance Collier adapted Ibbetson into a play. It was a hit on the London stage, and in 1917 Collier co-starred with the young John Barrymore on Broadway, as du Maurier’s star-crossed lovers who meet every night in their dreams. It was this version of du Maurier’s rambling and undisciplined tale that provided the framework for Vincent Lawrence and Waldemar Young’s script for Hathaway and his stars Gary Cooper and Ann Harding.

Hathaway wasn’t originally assigned to direct Peter Ibbetson; the job was supposed to go to Richard Wallace. Wallace (born, like Hathaway, in Sacramento) had just finished The Little Minister with Katharine Hepburn, and Ibbetson seemed like a good fit. But Gary Cooper, antsy over the script’s offbeat quality, insisted on Hathaway instead. (Hathaway was one of Cooper’s best friends and his favorite director, and eventually directed more of Cooper’s movies than anyone.) Shuffled off onto Annapolis Farewell, which had been Hathaway’s next slated assignment, Wallace flew off for the film’s Maryland location and was badly injured (though not killed) when his plane went down in Macon, Georgia; Annapolis Farewell was eventually directed by Alexander Hall.

Henry Hathaway didn’t often work with child actors, but when he did, he got good results (Spanky McFarland in The Trail of the Lonesome Pine, Dean Stockwell in Down to the Sea in Ships). And so it was with Dickie Moore and Virginia Weidler in Ibbetson. They play Cooper and Harding as kids, “Gogo” and “Mimsey”, when their souls become mated for life. The first of the movie’s poetic moments comes when the two are about to be separated, as Gogo’s gruff uncle is taking him from his Paris home after his mother’s death, to be raised in England; a closeup shows Weidler timidly taking Moore by the hand.

When they meet years later, Gogo is now Peter, a promising young architect, and Mimsey is Mary, the Duchess of Towers, whose husband the duke (John Halliday) has hired Peter to redesign the stables on his estate. At first they don’t recognize one another, but the realization comes one morning during Peter’s stay at the estate, when the two find they have shared the same dream the night before, of being caught in a sudden storm during a carriage ride.

It is in its last third that Peter Ibbetson becomes something rare and unforgettable, when the lovers are parted once again as Peter is sent to prison. The most sensible and satisfying change that Raphael and Collier made in their play was to alter the crime for which Peter goes away. In du Maurier’s novel, he cold-bloodedly murders the “uncle” who raised him when he learns that the man is really his biological father, a notorious rake who seduced and abandoned his mother, leaving her to die brokenhearted in Paris.

In the play and movie, the “crime” occurs in a confrontation with the drunken Duke of Towers. The duke brandishes a pistol, and Peter, accidentally and in self-defense, bashes his brains out with a chair. Tormented by the separation and tortured in prison, his back broken by a sadistic guard, Peter surrenders to despair, hoping only for death.

But Mary appears to him and proves that this is no delirium; they are really together in a dream, though separated by distance, stone and iron.

“You needn’t be afraid, Peter,” she says. “The strangest things are true, and the truest things are strange.”

“You needn’t be afraid, Peter,” she says. “The strangest things are true, and the truest things are strange.”

Peter gains courage to live for the nighttime, when they can be together. In du Maurier’s book, they spend years gallivanting through time and space, unfettered by a world that has grown unreal to them. (It gets more than a little tedious, truth be told.) In the movie, this is distilled into a transcendent 16-minute sequence, luminously photographed by Charles Lang (on some of the same locations Hathaway would soon showcase in Lonesome Pine), that takes Peter and Mary to a world of their own, brilliant with sunshine that contrasts sharply with his dank prison cell and her stately, forbidding manor house. It’s the climactic movement of a lush visual symphony.

Peter Ibbetson is an almost ineffably sublime experience. Never mind that Gary Cooper, playing an Englishman, never even tries to hide that Montana accent that persuaded some people all through his career (and still does) that he couldn’t act at all. His faith in Hathaway is well-justified, for this is an extraordinarily well-directed movie, and one of his most touching performances. Ann Harding, despite her golden beauty, was a cold fish on screen (“an absolute bitch,” according to Hathaway). It’s no coincidence that her only Oscar nomination came for playing the snooty older sister in Holiday (1930). She bridled at working with Cooper, feeling he gave her nothing in his acting, but she was wrong. In Ibbetson she glows in the reflected warmth of Cooper’s performance; we love her because he does.

The look of the movie is as sublime as Cooper’s acting. If Lives of a Bengal Lancer shows what Hathaway learned from Victor Fleming, Ibbetson shows the effect of having worked with Josef von Sternberg. Hathaway and Lang modeled their lighting on Rembrandt (“He taught you not to be afraid of the dark.”), and the compositions reinforce the romantic yearnings of the story. See how often the two lovers are separated by iron bars, walls — even, as children, the rails of the cast-iron fence between their homes. When, in dreams, they walk through the bars to be together, it’s a simple trick that any amateur shutterbug could explain to you, but it’s so perfectly right that it takes your breath away.

The look of the movie is as sublime as Cooper’s acting. If Lives of a Bengal Lancer shows what Hathaway learned from Victor Fleming, Ibbetson shows the effect of having worked with Josef von Sternberg. Hathaway and Lang modeled their lighting on Rembrandt (“He taught you not to be afraid of the dark.”), and the compositions reinforce the romantic yearnings of the story. See how often the two lovers are separated by iron bars, walls — even, as children, the rails of the cast-iron fence between their homes. When, in dreams, they walk through the bars to be together, it’s a simple trick that any amateur shutterbug could explain to you, but it’s so perfectly right that it takes your breath away.

Some seven years later, Hathaway directed Constance Collier, now a grand dowager of the theater, in The Dark Corner. One day, during a break on the set, she suddenly said, “Henry Hathaway. My God, you’re not the Henry Hathaway who made that dreadful picture out of my play Peter Ibbetson with that horrible man — that Gary Cooper. My God, you’re not that Hathaway!” He said, “I sure am,” and Collier dropped the subject. Hathaway was proud of his movie; he couldn’t understand why Collier was so offended. Neither can I.

Nor could a lot of people. Ernst Lubitsch said it was one of the best-directed movies he’d ever seen. To Luis Bunuel, it was “one of the world’s ten best films;” to Andre Breton, “a triumph of surrealist thought.” Even Pauline Kael, who called it “an essentially sickly gothic,” conceded Hathaway “brings off some of the ethereal moments, and the film tends to stay in the memory.”

It’ll stay in yours, too.

POSTSCRIPT: This concludes the opening salvo in my tribute to Henry Hathaway. I’ll post on some of his other movies from time to time, movies you may well have seen without knowing who directed them — some acknowledged classics, some neglected gems, some perhaps less successful ventures that still have things worth seeing. If Hathaway is fated to remain neglected and ignored for his tremendous body of work, I hope it won’t be because I never spoke up to defend him.