was the town where he lived much of his adult life (and where he died in 1946): Woodruff Place, named for James O. Woodruff, who owned the 80 acres where the town sat, about a mile-and-a-half northeast of downtown Indianapolis. Woodruff Place was characterized by wide avenues designed for horse-and-buggy traffic, multi-tiered fountains at the intersections, pseudo-European statuary posed under the magnolia and oak trees that lined the expansive streets, and stately, even pretentious upscale homes. Most stately and pretentious of all was Woodruff House itself. Here’s a postcard image of the house in its heyday (it was demolished in the 1930s); anyone who has read Tarkington’s novel (or seen Welles’s movie) will readily recognize the prototype of the Amberson Mansion, Tarkington’s “house of arches and turrets and girdling stone porches”.

Woodruff Place began in 1872 as a tony suburb for the prosperous merchants of Indianapolis, a parkland refuge from the soot and smoke of the growing city. It was incorporated as a town in 1876, even as Indianapolis crept out to engulf it. (James Woodruff, meanwhile, didn’t live to see the full flowering of his municipal namesake, dying at 38 of “congestion of the brain” in New York while planning an educational around-the-world cruise in 1879.)

New homes continued to rise for the rest of the 19th century, but the coming of the automobile accelerated both Indianapolis’s growth — by 1907, it was the fourth-largest manufacturer of cars in the world — and Woodruff Place’s decay. As cars made commuting more practical, residential suburbs sprouted ever farther from the city center, and by 1910 the town of Woodruff Place was surrounded on all sides by Indianapolis. Affluent citizens followed the city’s spreading outskirts, the industrial inner city grew, and the grand homes of Woodruff Place were subdivided into apartments, sometimes as many as eight or ten, for the burgeoning blue-collar population. Finally, in 1962, Woodruff Place’s long struggle for independence ended when it was annexed by Indianapolis. Today it is on the National Register of Historic Places and a designated preservation district by the City of Indianapolis.

Much of Woodruff Place’s decline came after even Booth Tarkington was dead, but the handwriting was on the wall decades earlier as he mapped out his

Growth trilogy. For this second volume, Woodruff Place became Amberson Addition (Tarkington’s description is unmistakeable), while James Orton Woodruff was transformed into the leonine Major Amberson (and permitted to live to a ripe old age). Tarkington saw what was happening to Woodruff Place, and he chose to portray it as reflected in the decline of a single family through their failure to cope with the changing times. And Tarkington’s symbol of that change was the automobile.

Magnificence, Tarkington writes, is always comparative; the magnificence of the Ambersons dated from 1873, when Major Amberson made his fortune, and it lasted “throughout all the years that saw their Midland town spread and darken into a city”. The Ambersons and their doings dominate the town’s activities and its conversations; everybody knows what they are up to and cares what they say, think and do. Major Amberson has six offspring, but only three of them figure in Tarkington’s plot: sons George and Sydney and daughter Isabel. Isabel in turn has two suitors: careful, quiet Wilbur Minafer (“a steady young businessman and a good church-goer”) and George’s best friend Eugene Morgan — dashing, charming, and a little wild.

One night, Eugene gets a bit too wild. In a state of inebriation while trying to serenade Isabel, he stumbles through a bass viol, reducing it to splinters and himself to a mumbling heap. Humiliated by his “making a clown of himself in her front yard”, Isabel refuses to accept his apologies or even to see him, and two weeks later announces her engagement to Wilbur. The wedding is a grand Amberson affair, the honeymoon as staid and careful as the groom, and Wilbur and Isabel move into their new house, a wedding present from the Major next door to (and almost as impressive as) his own, and they live there with Wilbur’s unmarried sister Fanny.

Isabel is a good and faithful wife to Wilbur, but she doesn’t really love him. A town dowager predicts that all her love will go to their children, “and she’ll ruin ’em.” The dowager is only partly wrong: Wilbur and Isabel don’t have children, they have one child.

By the time he is ten years old, George Amberson Minafer, the Major’s only grandchild and the apple of his adoring mother’s eye, is a spoiled rotten brat, lording it over local citizens and strutting around town as if he owns the whole place — which he assumes, by right of birth, he will someday. As a teenager he high-hats and bullies his supposed friends in a “secret club” they have formed when they dare to elect someone else president. The idea that he may be making enemies never enters Georgie’s mind; it’s other people’s job to curry favor with him. He dismisses anyone not an Amberson as “riffraff”. Among the solid citizens of the town, more than a few long for the day this haughty young prince will get his “comeuppance” (“Something was bound to take him down, some day, and they only wanted to be there!”).

So much for prologue. The Magnificent Ambersons really begins when 19-year-old George Minafer, now grown into a strikingly handsome young man, comes home from school for the Christmas holiday. His parents and grandfather host an elaborate formal soiree in his honor at the Major’s mansion. It is “the last of the great long-remembered dances that ‘everybody talked about'” — because, although the Ambersons may not realize it, their town is already growing too large for “everybody” to talk about anything.

At this party George comports himself according to his idea of noblesse oblige, pretending to remember people when he doesn’t (and, with some of his former boyhood friends, pretending he doesn’t know them when he does). One of the people he pretends to remember is none other than Eugene Morgan, now a widower with an 18-year-old daughter, returning to town for the first time since before George was born. George doesn’t know the history between his mother and Eugene, of course, but there’s something about the man that he doesn’t quite like.

Eugene’s daughter Lucy, however, is another matter. George likes her very much; he is instantly smitten. Lucy, for her part, takes a liking to him as well, despite his rather smug and grandiose airs, which, to his consternation, she finds slightly amusing.

Eugene spends the evening dancing with Isabel and with George’s Aunt Fanny and talking over old times with Uncle George, the Major, and his old rival Wilbur. Fanny — who, like many young women back in the day, was quite taken with Eugene — revels in his return, and in a quieter way, so does Isabel.

Young George’s suspicions are aroused when he learns that Eugene, who left town years ago as a struggling lawyer, has turned inventor and intends to establish a factory in town manufacturing horseless carriages. George insists that those noisy, unreliable machines will never amount to anything and suspects that Eugene is trying to weasel his way into the family’s graces to get the Major to invest in his fly-by-night operation. When Fanny defends Eugene, George teases her about setting her cap for him. Fanny angrily berates him for his “mean little mind”, and George is amazed to realize he must have struck a nerve.

George stifles his mild dislike for Eugene as he continues to court Lucy, never quite sure where he stands with her, but finding her so much more interesting than the “silly” girls he grew up with. Eugene, meanwhile, becomes a regular visitor in the Minafer home, taking Fanny and Isabel, and sometimes Uncle George, on frequent outings in his automobile. For all of them it seems like old times, which both amuses and unsettles young George.

Some time later, the first crack in Major Amberson’s vast fortune appears when Uncle Sydney and his wife Amelia — insufferable snobs — decide that the town isn’t fit for a “gentleman” to live in, and pressure the Major to give them their share of his estate now rather than make them wait to inherit it in his will. Uncle George holds that the estate can’t handle being broken up so soon, and in the ensuing squabble Amelia makes catty allusions to rumors going around about Eugene and Isabel. Young George, his latent antipathy aroused, is alarmed, but Aunt Fanny, herself infatuated with Morgan, pooh-poohs the idea, while Uncle George dismisses it as the idle gabble of the malicious and greedy Amelia.

During young George’s senior year at college, Wilbur Minafer dies, the victim of a listless constitution and his worries about a business that died just before he did, taking all the Minafer money with it. Wilbur’s death therefore leaves Fanny penniless and at the mercy of her Amberson in-laws. Isabel and George agree that Fanny should continue to live with them, and they assign Wilbur’s life insurance money to her to give her something of a nest-egg. Still, she remains bereft, insecure and emotionally fragile; when Georgie returns home after graduation and teases her anew about Eugene Morgan, she is quickly driven to tears.

Also on his return from college, George is appalled to discover that the broad lawn between the Amberson Mansion and his and Isabel’s house has been subdivided by the Major to build five smaller houses as rental properties. George’s aesthetic sensibilities are offended; even more offensive is the idea of strangers — riffraff — interloping on Amberson property. Uncle George fails to impress on his nephew the idea that perhaps the Major needs the money. Later, when George asks his grandfather to buy a larger two-horse carriage, or even a four-in-hand, the Major temporizes, then mumbles something about helping George get through law school. George fails to make the obvious connection; he worries that the Major is getting senile.

Eugene Morgan continues a frequent visitor at the Amberson and Minafer homes, taking Isabel and Fanny — sometimes the Major, or Uncle George, or young George too, but always Isabel — for drives in his motorcar. Georgie, for his part, prefers buggy rides with Lucy, but his courtship is not going well. Whenever he presses her to become engaged, she sadly parries his advances. Finally George gets her to admit that she is concerned for her father’s approval and uneasy about George’s reluctance to “make something of himself”. George is affronted; why should he make something of himself when he’s already an Amberson? The very suggestion that he enter some profession insults him. He becomes quarrelsome, and he and Lucy are estranged.

That same evening, on their front porch, as Fanny and Isabel chat, George daydreams of Lucy begging his forgiveness, promising she will never listen to her father again, that she now dislikes him just as much as George does. This is followed by another, less pleasant fantasy: He imagines Lucy surrounded by young men — the same ones he bullied and dominated when they were boys — and laughing gaily, giving no thought to him. Riffraff! George continues to stew over his foundering romance with Lucy, and what he sees as Eugene’s meddling in his personal life. (Everything is always about George Amberson Minafer.)

One night, when Eugene comes to dinner — without Lucy — George’s resentment boils over. As Eugene and the Major chat about Eugene’s flourishing automobile factory, George blurts out that automobiles are a useless nuisance; they’ll never amount to anything and had no business being invented. In the awkward silence that follows, the Major chides George for his tactlessness. Eugene’s answer is worth quoting because it has become — partly due to the abbreviated version of it that appears in Orson Welles’s movie — the most famous passage from the novel:

“I’m not sure he’s wrong about automobiles. With all their speed forward they may be a step backward in civilization — that is, in spiritual civilization. It may be that they will not add to the beauty of the world, nor to the life of men’s souls. I am not sure. But automobiles have come, and they bring a greater change in our life than most of us suspect. They are here, and almost all outward things are going to be different because of what they bring. They are going to alter war, and they are going to alter peace. I think men’s minds are going to be changed in subtle ways because of automobiles; just how, though, I could hardly guess. But you can’t have the immense outward changes that they will cause without some inward ones, and it may be that George is right, and that the spiritual alteration will be bad for us. Perhaps, ten or twenty years from now, if we can see the inward change in men by that time, I shouldn’t be able to defend the gasoline engine, but would have to agree with him that automobiles ‘had no business to be invented.'”

Eugene excuses himself and leaves, while Isabel, Fanny and the Major wonder at George’s rudeness. Isabel asks George why he dislikes Eugene so, but he denies disliking him — or liking him, for that matter. He affects a pose of lofty indifference, although he is slightly perplexed when Aunt Fanny hastily whispers to him that he has “struck just the right treatment to adopt”.

Some time later, when George, still brooding over his break with Lucy, again snubs Eugene, Fanny sees it and comes to George’s room to congratulate him. She knows exactly what he’s doing, she says, but she doesn’t. In fact, she has let her own frustrated dreams of marrying Eugene Morgan poison her, and the poison festers as she sees long-buried feelings blossoming again between Eugene and Isabel. Now, misunderstanding George’s motives, she says she understands that he’s only trying to protect his mother’s reputation, that he’d give up Lucy in a minute if it was a matter of Isabel’s good name.

George is thunderstruck. In his self-absorption he hasn’t given a thought to Eugene and Isabel, but now, badgering the sputtering Fanny, he learns that Aunt Amelia was right, there has been talk about them, and it has only increased since Wilbur’s death. Fanny thought he already knew, but in fact she’s the one who has told him. Now she tries to restrain him, but he flies into a fury.

George storms across the street to confront Fanny’s friend Mrs. Johnson, a notorious gossip. Imperious as always, he demands to know who has been slandering his mother’s name, but she indignantly orders him out of her house. When George turns to his uncle, Uncle George is appalled at what George has done. Doesn’t he realize that he’s only thrown fuel on the fire? Gossip is never fatal until it’s denied, he says. Worse yet, in his nephew’s eyes, he appears unperturbed at the thought of Eugene and Isabel marrying; why shouldn’t they, he says, if they’re both free and care about each other? Young George calls the idea “monstrous”.

It is clear to Georgie that it’s up to him to defend his mother’s good name — the Amberson name — not to mention the memory of his father (whom he barely noticed when he was alive). When Eugene comes to the door to take Isabel driving, George intercepts him, refuses to let him in, tells him he is no longer welcome, and slams the door in his face.

Isabel waits in vain all afternoon for Eugene to come for her. Instead, late that evening, her brother George arrives, takes her into the parlor and closes the door. Fanny stops Georgie from barging in on them; She knows Uncle George is telling Isabel what her son has done. Too late, Fanny realizes the damage she has done, and is aghast. She realizes that she’s been a fool; she never had a chance with Morgan, and wouldn’t have had, even if Wilbur had lived. She was only letting off steam, and now look what she’s done.

Uncle George has brought a letter from Eugene pleading with Isabel to stand up to her son for the sake of their happiness. But George remains adamant, and the heartbroken Isabel can’t bring herself to go against his wishes. She breaks it off with Eugene once again. “This time,” he laments, “I’ve not deserved it.”

The next day George encounters Lucy downtown. It is clear she doesn’t yet know about the scene with Eugene. She is friendly and cordial, but she keeps the conversation light and trivial, which frustrates George. He had thought losing Lucy would be “no great sacrifice”, but now that he sees her, and she offers no hint of their former intimacy, he knows otherwise. Reminding him of their quarrel, she says since they can’t “play nicely”, they’d best not play at all. He tells her that he and Isabel are going away soon — indefinitely, perhaps permanently — and he may never see her again. She expresses casual regret but wishes him “ever so jolly a time”. Stung, he stalks off. Only when he is gone does Lucy show her true feelings, nearly swooning inside a nearby shop. When she gets home, she finds Fanny Minafer waiting for her, and at last she hears about what George has done to her father. Immediately after Fanny leaves, Lucy burns George’s pictures and all his letters.

The next day George and his mother leave on a round-the-world tour. Fanny has warned George that Isabel’s health is not good, but he refuses to believe it, says she’s the healthiest person he knows. In their absence, real estate values in Amberson Addition decline sharply, so much that the Major is unable to rent all of the new houses he had built.

One evening, relaxing on the veranda, Fanny and Uncle George fall to talking about money-making opportunities in the face of the dwindling Amberson fortune. Old Frank Bronson, the Major’s lawyer, has told George about a new company planning to manufacture automobile headlights; with the proliferation of motorcars like Eugene Morgan’s, this could prove to be a lucrative investment. Fanny and George agree to consider putting some money into the company, agreeing also not to invest more than they can afford to lose.

They ask Eugene’s opinion, and he advises caution, but by then Fanny and George have “the fever” and see the headlight company as a sure-fire way to get rich quick. They both “plunge” on the company, forgetting their resolve not to invest too much. It’s a decision that will have serious consequences.

Eugene Morgan’s factory continues to prosper. Soon he and Lucy are able to move from the modest house they have been renting into a luxurious new mansion which Eugene has built in a new suburb of the city, farther from the center of town and less vulnerable to the urban smoke and soot that have blighted Amberson Addition. George Amberson comes to see them after a visit to Paris where Isabel and young George are staying. The elder George tells them he was alarmed at the evident decline in Isabel’s health; he tells them also that his nephew refuses to see it. He says he sensed that Isabel wants to come home, but that Georgie, without actually using force, refuses to let her. One night, Amberson says, Isabel expressed a wish to see her father once more, and it struck him that his sister was more worried about the state of her own health than about the Major’s.

Finally, after nearly a year and a half abroad, even young George can see that they must return home now if his mother is ever to withstand the journey. As it is, the trip home is so arduous that by the time they arrive Isabel is too weak to walk a step, and Georgie has to carry her up to her room. A doctor and nurse have been summoned and are waiting. Fanny, Uncle George and the Major are desolate, understanding — as young George does not, quite — that Isabel is on her deathbed.

Eugene Morgan hears, and comes to see Isabel, but George again refuses to let him in; if it weren’t for Morgan, he says, none of this would have happened. When Isabel learns that Eugene has been there, she whispers that she would have liked to see him — just once. The next morning she is dead.

Young George is dazed and devastated; he had been clinging to the forlorn hope that she might get better. Even a month later, he is still answering the unspoken reproaches he imagines coming from Uncle George and Aunt Fanny. “What else could I have done?” Before long, his question becomes, “If I was wrong, couldn’t someone have stopped me?” Fanny tells him, bleakly, that no, nobody could stop him; he was too strong, and Isabel loved him too much.

On some level, George seems to understand that his mother died of a broken heart, and that it was he and not Eugene Morgan who broke it. And even in his wretched grief and denial, he certainly knows this: He refused his mother’s dying wish to see Eugene one last time.

With Isabel’s death, the fall of the House of Amberson gathers a terrible momentum. Major Amberson withdraws into his own private contemplation of mortality, where his son and grandson can no longer reach him. The headlight company where Uncle George and Fanny put so much money fails, never having resolved the technical flaws in the product. No one can find a clear title to Isabel’s house, the wedding present from the Major so many years ago; it seems the Major neglected to transfer the deed to Isabel or to register it with the county land office. Nor is the Major any help; his mind seems elsewhere. The two Georges hesitate to question him on the matter, but they hesitate too long; one morning a servant finds the Major dead in the easy chair by his bedroom window.

Between the money Uncle George invested in the headlight company and the share that Sydney and Amelia took (which turns out to have been the only share that was really worth anything), the Major has died virtually penniless. Sydney and Amelia, now living like royalty in their Italian villa, decline to help.

Young George loses his mother’s house and land, and is able to clear only about $600 from the sale of Isabel’s furniture and clothes. Uncle George, thanks to his political connections, lands a minor consulship in South America, but even then he must borrow $200 from his nephew to make the trip to his new home. At their last meeting, before boarding his train, uncle tells nephew that he’s always been fond of him — hasn’t always liked him, but always been fond. You’ve had some hard blows lately, he says, and you’ve taken them like a man. There may be others in this town who are fond of you too; don’t be too proud to turn to them. And with that he is gone; both men understand that they will never see each other again.

George’s only prospect now is an $8-a-week job as law clerk to Frank Bronson, with the prospect of on-the-job training, eventually to become a lawyer himself. He and Fanny must vacate the Minafer home, and Fanny has found a place for them in a boarding house across town where some of her old acquaintances are living. But when Fanny and George look closely at their finances, they find that, for all intents and purposes, they have none. Fanny had in fact, despite her assurances to the contrary, invested every penny she had in the headlight company, and now it’s gone; she has only $28 left to her name. George, after dismissing the servants and staking his uncle, has only about $200 left. The boarding house is going to cost, at a minimum, $100 a month. And George will be making $32.

George tells Frank Bronson that he can’t take the job, and he hasn’t time to wait to become a lawyer. He needs something that pays well right away. Bronson protests, but George explains that, well, he has much to atone for in his life, and he can’t really make it up to the people he owes it to. The next best thing is to behave decently to poor Fanny, whom he has never really treated very well. Now George has heard that there are well-paying jobs for men in dangerous professions — handling chemicals or explosives, things like that. Bronson reluctantly agrees to help George find such a job: “You certainly are the most practical young man I ever met!”

All this time, Lucy still has feelings for George, and she indirectly admits as much to her father. He doesn’t tell her that he has learned that George has found a job handling nitroglycerin at a chemical plant — a job with a high mortality rate. An old friend tells Eugene that George seems to be trying to do the decent thing for “old Fanny”, and he hints that he (Eugene) might find a safer job for George. Eugene is in fact a silent partner in that chemical plant, and could arrange something without George ever knowing. But Eugene, still bitter, is unwilling to do George any favors.

On one of his Sunday walks, while Fanny is at church, George takes a melancholy stroll through Amberson Addition. The once-stately houses are now rundown, soot-stained and seedy, converted into apartment buildings, boarding houses, shops, lodge halls and the like — or, like the Amberson Mansion and Isabel and Wilbur’s old house, demolished, waiting for the rubble to be carted away. Even the newer houses the Major built as rental properties have been pulled down. The fountains at the intersections are dry and crumbling, the statues lining the streets corroded and pitted. All that’s left of the family name, he muses, is the name of Amberson Boulevard itself. But a corner street sign disabuses him: Amberson Boulevard has been changed to Tenth Street.

Returning to the boarding house, George remembers a book he saw in the parlor, a municipal tome chronicling the 500 most prominent families in the history of the city. He takes the book down, opens to the index, and looks over the names listed there: Abbett, Abbott, Abrams, Adam, Adams, Adler, Akers, Albertsmeyer, Alexander, Allen, Ambrose, Ambuhl, Anderson…

George stares a long time at the page. Five hundred families, and there’s nothing between “Allen” and “Ambrose”. He puts the book back on the shelf. Something has happened that has been a long time coming: Georgie Minafer has had his comeuppance — “three times filled and running over.” But all those people who so longed for it are not there to see it. “Those who were still living had forgotten all about it and all about him.”

In the end, it’s not the nitroglycerin that gets George. Of all things, it’s an automobile. One Sunday, walking downtown, he remembers seeing a young lady stepping into an expensive motorcar. He thought at the time that it might be Lucy, but he couldn’t be sure. Now, standing in the street, he remembers back to that day, and while he’s standing there thinking about the auto in his memory, another auto in the here-and-now runs him down, breaking both his legs. As George lies there in a haze of agony, the driver jumps out of his car and begins jabbering to police that it wasn’t his fault; he’s sorry for George but it wasn’t his fault, and he has a witness. As George lies there dusty and bloodied, waiting for the ambulance, he mutters, “Riffraff!”

Eugene Morgan reads about George’s accident in the paper while on his way to New York on business. His bitterness toward George is unchanged by the young man’s misfortune, but somehow in his reverie he senses the presence of Isabel, and can see her wistful eyes, more than at any time since her death. In New York, on an impulse, he goes to see a spiritual medium, a woman he had visited once before and dismissed as a fake. Now, however, the woman gives him an ambiguous reading that faintly suggests a message from Isabel: A beautiful lady, she says, wants him to “be kind”.

Has Eugene subconsciously fed cues to the woman that enabled her to lead him on this way, or was she really in touch with Isabel? Eugene can’t be sure, but when he returns home he goes straight from the station to the hospital where George is convalescing. He isn’t surprised to find Lucy already there.

Nor is George surprised to see Eugene. “You must have known my mother wanted you to come, so that I could ask you to — to forgive me.”

Eugene takes George’s hand, and Tarkington’s novel ends thus:

But for Eugene another radiance filled the room. He knew that he had been true at last to his true love, and that through him she had brought her boy under shelter again. Her eyes would look wistful no more.

* * *

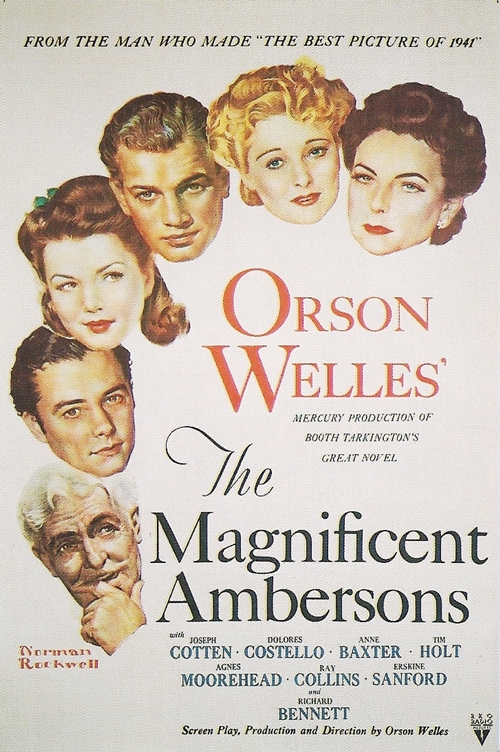

Orson Welles and the Mercury Theatre took a different tack. I have illustrated this post with pictures from Welles’s movie, but the synopsis is of the original novel. I have gone into considerable detail for reasons that I think will become clear as we discuss what happened when Welles brought his version to the screen. We’ll move on to that in Part 2.

Somewhere around the time the story of The Magnificent Ambersons closes — Booth Tarkington was a little hazy on dates — George Orson Welles was born, on May 6, 1915, in Kenosha, Wisconsin. This is how little Orson looked when The Magnificent Ambersons was published in 1918.

Somewhere around the time the story of The Magnificent Ambersons closes — Booth Tarkington was a little hazy on dates — George Orson Welles was born, on May 6, 1915, in Kenosha, Wisconsin. This is how little Orson looked when The Magnificent Ambersons was published in 1918.

When Welles presented Ambersons on Campbell Playhouse he was already under contract to RKO, though he wouldn’t start work on Citizen Kane for several months. Maybe he really did have an early affection for Tarkington’s book — why else would he have done it on radio in the first place? — but when it came time to choose his second picture as writer-director, he may well have picked it largely because the radio drama had already given him a head start on it. With everything else he had going on, who could blame him? He played a recording of the show for RKO president George Schaefer, who green-lighted the production on the strength of that. (Welles told biographer Barbara Leaming that five minutes into the recording, Schaefer dozed off, waking up only at the end, then giving the go-ahead. Like the story of Tarkington and his father, this one seems not to have surfaced while Schaefer was around to dispute it; he died in 1981 at 92, and Leaming’s 1985 biography was the earliest mention I could find of Schaefer’s nap.)

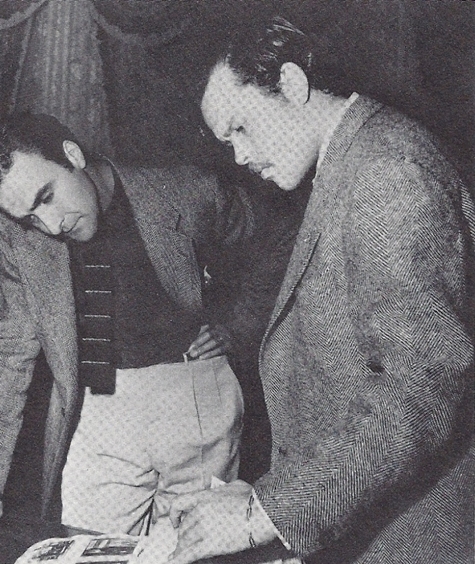

When Welles presented Ambersons on Campbell Playhouse he was already under contract to RKO, though he wouldn’t start work on Citizen Kane for several months. Maybe he really did have an early affection for Tarkington’s book — why else would he have done it on radio in the first place? — but when it came time to choose his second picture as writer-director, he may well have picked it largely because the radio drama had already given him a head start on it. With everything else he had going on, who could blame him? He played a recording of the show for RKO president George Schaefer, who green-lighted the production on the strength of that. (Welles told biographer Barbara Leaming that five minutes into the recording, Schaefer dozed off, waking up only at the end, then giving the go-ahead. Like the story of Tarkington and his father, this one seems not to have surfaced while Schaefer was around to dispute it; he died in 1981 at 92, and Leaming’s 1985 biography was the earliest mention I could find of Schaefer’s nap.) Principal photography began in late October 1941 with the dinner table scene where Georgie denounces the automobile and deliberately offends Eugene Morgan. All things considered, the shoot went well. But there were things to be considered. For one thing, Welles lost cinematographer Gregg Toland, his most valuable and stimulating collaborator on Kane, when Toland enlisted in the U.S. Navy’s photography unit. A last-minute replacement was Stanley Cortez (shown here with Welles). Cortez proved to be an inspired choice, but his slow, methodical style contrasted sharply with the swift, no-nonsense Toland and caused Welles no end of frustration.

Principal photography began in late October 1941 with the dinner table scene where Georgie denounces the automobile and deliberately offends Eugene Morgan. All things considered, the shoot went well. But there were things to be considered. For one thing, Welles lost cinematographer Gregg Toland, his most valuable and stimulating collaborator on Kane, when Toland enlisted in the U.S. Navy’s photography unit. A last-minute replacement was Stanley Cortez (shown here with Welles). Cortez proved to be an inspired choice, but his slow, methodical style contrasted sharply with the swift, no-nonsense Toland and caused Welles no end of frustration.

It happens to be my personal opinion that Citizen Kane is Orson Welles’s second greatest movie; I prefer The Magnificent Ambersons, and by a considerable margin. Maybe it’s because I first discovered Ambersons on late-night TV in the early 1960s, a good four years before I first saw Kane. I hadn’t yet heard all the tales and legends behind the making (and editing) of the picture, so I didn’t know I was supposed to regard it with sorrowful disdain as The Great Saint Orson’s might-have-been masterpiece yanked from his loving hands and mutilated by the mindless paws of lesser, crasser men. All I knew was what I saw on the screen, and I thought it was a terrific movie. I still do.

It happens to be my personal opinion that Citizen Kane is Orson Welles’s second greatest movie; I prefer The Magnificent Ambersons, and by a considerable margin. Maybe it’s because I first discovered Ambersons on late-night TV in the early 1960s, a good four years before I first saw Kane. I hadn’t yet heard all the tales and legends behind the making (and editing) of the picture, so I didn’t know I was supposed to regard it with sorrowful disdain as The Great Saint Orson’s might-have-been masterpiece yanked from his loving hands and mutilated by the mindless paws of lesser, crasser men. All I knew was what I saw on the screen, and I thought it was a terrific movie. I still do. The Magnificent Ambersons, first of all, was a novel that won author Booth Tarkington the first of his two Pulitzer Prizes (the second came three years later for Alice Adams). Born in 1869 in Indianapolis, Tarkington was successful right out of the chute with his first novel, The Gentleman from Indiana, published when he was 30. He was popular and prolific, turning out some 53 novels, plays and nonfiction books, including one published posthumously in 1947. Like many of his contemporaries, he has drifted out of fashion, but in his day he was nationally famous and well respected; his Penrod books, idealized yarns of mischievous childhood, gave Mark Twain’s Tom and Huck a good run for their money, and in 1922 the Literary Digest proclaimed him “America’s greatest living writer”.

The Magnificent Ambersons, first of all, was a novel that won author Booth Tarkington the first of his two Pulitzer Prizes (the second came three years later for Alice Adams). Born in 1869 in Indianapolis, Tarkington was successful right out of the chute with his first novel, The Gentleman from Indiana, published when he was 30. He was popular and prolific, turning out some 53 novels, plays and nonfiction books, including one published posthumously in 1947. Like many of his contemporaries, he has drifted out of fashion, but in his day he was nationally famous and well respected; his Penrod books, idealized yarns of mischievous childhood, gave Mark Twain’s Tom and Huck a good run for their money, and in 1922 the Literary Digest proclaimed him “America’s greatest living writer”.

In 1949 Henry Hathaway made one of the best movies of his long career. In it, his three stars, Richard Widmark, Lionel Barrymore and Dean Stockwell (and for that matter, most of the supporting cast) each gave one of his own best performances. Down to the Sea in Ships is in fact one of the finest movies ever to come out of the Hollywood studio system, and almost nobody has ever heard of it.

In 1949 Henry Hathaway made one of the best movies of his long career. In it, his three stars, Richard Widmark, Lionel Barrymore and Dean Stockwell (and for that matter, most of the supporting cast) each gave one of his own best performances. Down to the Sea in Ships is in fact one of the finest movies ever to come out of the Hollywood studio system, and almost nobody has ever heard of it. After the war, Zanuck reactivated the project and handed it over to producer Louis D. (“Buddy”) Lighton and director Hathaway. Both men were working for Fox now, but they had been paired before in the 1930s at Paramount: Lighton had produced the Shirley Temple vehicle Now and Forever, The Lives of a Bengal Lancer, and

After the war, Zanuck reactivated the project and handed it over to producer Louis D. (“Buddy”) Lighton and director Hathaway. Both men were working for Fox now, but they had been paired before in the 1930s at Paramount: Lighton had produced the Shirley Temple vehicle Now and Forever, The Lives of a Bengal Lancer, and  Music historian Jon Burlingame (in his notes for the movie’s soundtrack CD) says Bartlett’s script underwent a rewrite by John Lee Mahin — shown here (on the left) in a rare acting stint in Hell Below (1933) with Robert Montgomery. Like Bartlett a reporter-turned-screenwriter, Mahin already had a number of major credits on his resume, many of them — including Red Dust, Treasure Island (1934), Test Pilot, Captains Courageous and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1941) — for Hathaway’s mentor Victor Fleming.

Music historian Jon Burlingame (in his notes for the movie’s soundtrack CD) says Bartlett’s script underwent a rewrite by John Lee Mahin — shown here (on the left) in a rare acting stint in Hell Below (1933) with Robert Montgomery. Like Bartlett a reporter-turned-screenwriter, Mahin already had a number of major credits on his resume, many of them — including Red Dust, Treasure Island (1934), Test Pilot, Captains Courageous and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1941) — for Hathaway’s mentor Victor Fleming.

Lunceford has no choice but to accept the assignment, but he does so with ill grace. Resentful at what he regards as essentially a babysitting chore, he is impatient, sarcastic and dismissive. Resentful in turn, Jed is obstreperous and uncooperative. Lunceford decides Jed is just as ornery and pigheaded as his grandfather, and he give up the lessons as a waste of his time.

Lunceford has no choice but to accept the assignment, but he does so with ill grace. Resentful at what he regards as essentially a babysitting chore, he is impatient, sarcastic and dismissive. Resentful in turn, Jed is obstreperous and uncooperative. Lunceford decides Jed is just as ornery and pigheaded as his grandfather, and he give up the lessons as a waste of his time. All this, mind you, while the movie does not skimp on action and high adventure. There are scenes of whale chases and boats lost at sea, suspenseful and beautifully shot (Joe MacDonald) and edited (Dorothy Spencer), with excellent special effects (Fred Sersen and Ray Kellogg). Capping it all is a climactic sequence in which the Pride of New Bedford runs aground on an iceberg in the fog near the horn of South America…

All this, mind you, while the movie does not skimp on action and high adventure. There are scenes of whale chases and boats lost at sea, suspenseful and beautifully shot (Joe MacDonald) and edited (Dorothy Spencer), with excellent special effects (Fred Sersen and Ray Kellogg). Capping it all is a climactic sequence in which the Pride of New Bedford runs aground on an iceberg in the fog near the horn of South America… …with the crew desperately struggling to free themselves and repair the damage before the sea pounds their ship to splinters against the unforgiving ice. Not to mince words, it’s an absolutely brilliant action/suspense set piece. Amazingly enough, it was shot entirely in a soundstage tank on the Fox lot, but it’s spectacularly convincing and harrowing for all that.

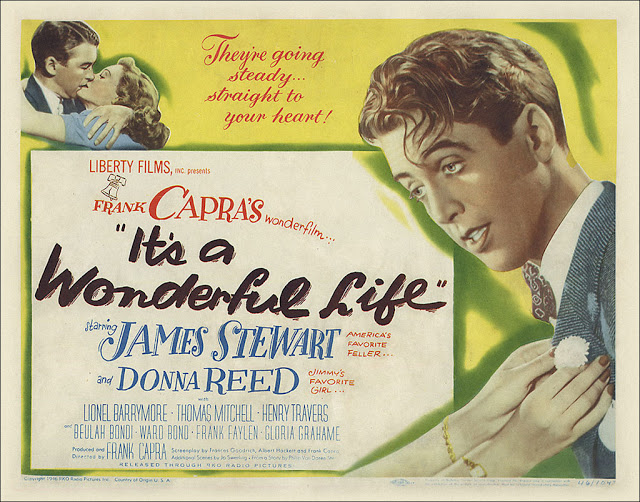

…with the crew desperately struggling to free themselves and repair the damage before the sea pounds their ship to splinters against the unforgiving ice. Not to mince words, it’s an absolutely brilliant action/suspense set piece. Amazingly enough, it was shot entirely in a soundstage tank on the Fox lot, but it’s spectacularly convincing and harrowing for all that. Down to the Sea in Ships was Lionel Barrymore’s last starring role, on loan from MGM. Once, when introducing Barrymore on a 1939 radio broadcast, Orson Welles referred to him as “the most beloved actor of our time.” It was probably an exaggeration, but not by much; Barrymore’s stock in trade was playing cantankerous old codgers with hearts of gold. Ironic, then, that the only role for which he’s widely remembered today is Old Man Potter in It’s a Wonderful Life, one of the most thoroughly heartless characters in the history of movies. In his own day Barrymore was more closely identified with wise old Dr. Gillespie in MGM’s Dr. Kildare series, and with his annual holiday performances as Ebenezer Scrooge on radio. In fact, Barrymore had been slated to play Scrooge in MGM’s A Christmas Carol (1938) until he broke his hip in an auto accident. That injury landed him in a wheelchair, then advancing arthritis kept him there for the rest of his career — until Down to the Sea in Ships.

Down to the Sea in Ships was Lionel Barrymore’s last starring role, on loan from MGM. Once, when introducing Barrymore on a 1939 radio broadcast, Orson Welles referred to him as “the most beloved actor of our time.” It was probably an exaggeration, but not by much; Barrymore’s stock in trade was playing cantankerous old codgers with hearts of gold. Ironic, then, that the only role for which he’s widely remembered today is Old Man Potter in It’s a Wonderful Life, one of the most thoroughly heartless characters in the history of movies. In his own day Barrymore was more closely identified with wise old Dr. Gillespie in MGM’s Dr. Kildare series, and with his annual holiday performances as Ebenezer Scrooge on radio. In fact, Barrymore had been slated to play Scrooge in MGM’s A Christmas Carol (1938) until he broke his hip in an auto accident. That injury landed him in a wheelchair, then advancing arthritis kept him there for the rest of his career — until Down to the Sea in Ships.