This post is my contribution to The Best Hitchcock

Films Hitchcock Never Made, a blogathon hosted

by my Classic Movie Blog Association buddies

Dorian at Tales of the Easily Distracted and Becky

at ClassicBecky’s Brain Food. For other posts in

this most excellent assortment of essays,

click on the blogathon link above.

For my part…well, once again I’ve done

my best to come up with a little gem

you never heard of.

Here goes…

I’ve chosen Frank Launder and Sidney Gilliat’s State Secret. If you’re a real Hitchcock buff, Launder and Gilliat’s names will give you an instant link with the Master. But before I get to that, there are a couple of erroneous points I need to clear up.

First and foremost, the title of this 1950 British thriller is definitely not The Great Manhunt, and it never was. Ever. Anywhere it played. You don’t know that if you go only by its page on the IMDb or Clive Hirschhorn’s The Columbia Story; both sources give The Great Manhunt as State Secret‘s U.S. release title. But film collector Eric Spilker assures us — and Eric never opens his mouth unless he knows what he’s talking about — that the picture opened in the U.S. as State Secret and played that way everywhere, even when it turned up on TV. Evidently Columbia made some early press releases announcing it as The Great Manhunt (a title they also announced, then discarded, for 1949’s The Doolins of Oklahoma), then thought better of it. In any case, the lobby card I’ve reproduced here says “Columbia Pictures presents”, showing clearly that it’s from the U.S. release, so there you have it. (The IMDb listing is particularly puzzling, since their standard policy is to list a movie under its title in its country of origin, but in this case it’s the other way round, giving the [erroneous] U.S. title first.) (And to add to the confusion there’s this at iOffer.com, i-offering the DVD as The Great Manhunt; I suspect they may have simply picked up the error from Clive Hirschhorn or the IMDb.)

Also on the IMDb is the claim that the picture was based on a novel by Roy Huggins, the writer who later went on to create, produce and/or write for the TV series

Maverick,

The Virginian,

The Fugitive, and

The Rockford Files, among others. I have no idea where that notion came from; there’s no mention of Huggins in

State Secret‘s screen credits, or in Variety’s review. In 2001, when the picture was screened at

Cinevent in Columbus, OH, the program notes went even further, saying that the source was Huggins’s novel

Appointment with Fear. In fact,

Appointment with Fear was a

noir novelette by Huggins that appeared in the Saturday Evening Post on September 28, 1946, about an L.A. private eye embroiled in a murder case in Tucson, AZ. And by the way, as if these waters weren’t already muddy enough, the IMDb claims that

Appointment with Fear was the basis for another 1950 movie, a Jack Carson farce called

The Good Humor Man; I haven’t seen that picture, but the idea is marginally more credible, since (like Huggins’s story)

The Good Humor Man appears to concern a man investigating a murder in which he’s the chief suspect. But I digress.

So, getting back to State Secret. It was never The Great Manhunt, and Roy Huggins had nothing to do with it. Now shall we proceed?

SPOILER ALERT: Before getting into the picture itself, here’s fair warning: Since State Secret is not officially available for home viewing — it is, however, available from iOffer.com at the link above, and also here from Loving the Classics — I’m going to go ahead and summarize the entire plot, including the ending. If you don’t want to tag along that far, never fear; there’ll be another warning before you get to anything you don’t want to read. (And for your information, the frame-caps illustrating this post are from Loving the Classics’ version of the DVD, so if you’re thinking you might like to buy it you’ll have an idea what you’d get from them.)

Frank Launder and Sidney Gilliat (sometimes spelled Gilliatt) had a partnership that spanned some 36 years and 37 pictures — from Seven Sinners (U.S.: Doomed Cargo) in 1936 to Ooh…You Are Awful! (U.S.: Get Charlie Tully) in 1972. Both men were equally adept at writing, producing and directing, and they mixed and matched duties as the situation required. As I said before, Hitchcock buffs will probably recognize them as co-authors of the screenplay (from Ethel Lina White’s novel) for The Lady Vanishes, one of Hitchcock’s best British pictures. (Personally, I’d say it’s the best; I find The 39 Steps just a teensy-weensy bit overrated, and I think Launder and Gilliat’s script makes the difference.) Gilliat also worked with Hitchcock on Jamaica Inn (1939), and he and Launder wrote Night Train to Munich, a Hitchcockian thriller directed by Carol Reed in 1940.

Launder gets an authorial credit here, on the movie’s title card, but in fact it’s the only time his name appears in the credits; the picture was written and directed by Gilliat on his own. No doubt there was some collaboration between the partners, but Launder was more comfortable with comedies like Lady Godiva Rides Again (U.S.: Bikini Baby) and The Belles of St. Trinian’s. In any event, the team’s Hitchcockian pedigree was unassailable, and it served Gilliat well here.

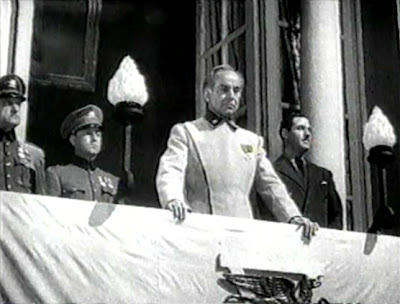

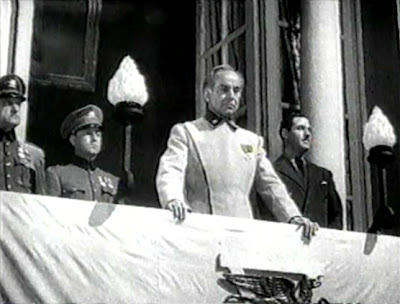

State Secret opens with an almost whimsical title: “You won’t find the State of Vosnia on any map, nor can you buy a dictionary of the language in any bookshop. Still — let’s face it — Vosnia exists: and any resemblance it may have to any other State, past or present, living or dead, is hardly coincidental.” As the name “Vosnia” suggests, the real-life version of this non-coincidental resemblance is Yugoslavia and its dictator-president-for-life Marshal Josip Broz Tito. Vosnia’s head of state is General Niva (Walter Rilla), whom we first see on the balcony of the People’s Palace in the capital city of Strelna, where he is expected to announce his campaign for re-election as prime minister (he is, oddly enough, running unopposed) before a carefully-orchestrated display of spontaneous public adoration. General Niva’s police state is a tightly-run personality cult; Niva’s picture is everywhere (George Orwell’s Big Brother — to say nothing of real-life characters like Tito, Peron and Stalin — was prominent in everyone’s mind when State Secret went into production). Half the orphanages, hospitals and highways in Vosnia are named for General Niva; when his face appears in the cinema newsreels or his name is mentioned in public, no one wants to risk being the last to join in the applause.

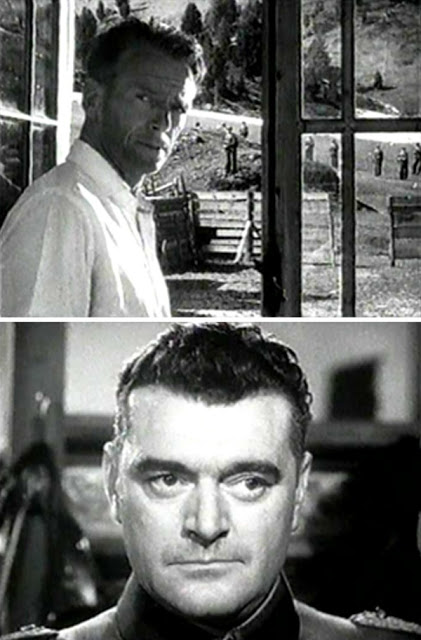

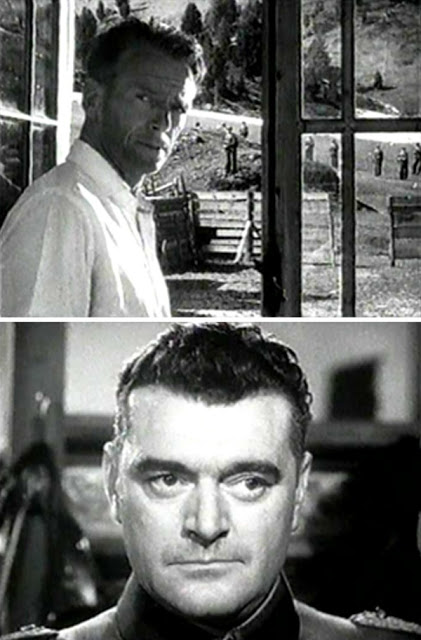

Meanwhile, at an undisclosed location some distance

from Strelna — in time we will learn just how far — two men

are listening to a radio broadcast of the crowd wildly cheering

and hailing General Niva. One is Dr. John Marlowe (Douglas

Fairbanks Jr.), an American surgeon who at the moment

looks rather the worse for wear. His appearance contrasts

sharply with the other man in the room, the crisply

uniformed, almost dapper Colonel Galcon (Jack Hawkins).

Marlowe has just finished tending to a bedridden woman

in the next room. “It will serve very little purpose,”

Galcon says; “however, I said that I would not

refuse any reasonable request.”

Smoking one last cigarette, Marlowe drifts to the

window, where he sees the hillside posted with a

daunting number of guards. Galcon assures him

that the view is the same on the other side. “Shot

while escaping, eh?” asks Marlowe. “No no,” says

Galcon, “a shooting accident. We have to think of

the newspapers.” Evidently resigned, Marlowe

nevertheless says that he still believes the truth

will come out. Galcon asks why. Marlowe thinks,

Why indeed?, and his mind turns back to when

this all began. When was it? Only two weeks ago?

As the screen ripples into flashback, we learn more about Dr. Marlowe. He has been on a four-month busman’s holiday in London, where he has been demonstrating a revolutionary new surgical technique he developed for the treatment of “portal hypertension”, a hitherto untreatable condition. (Portal hypertension is a real malady, having to do with high pressure in the blood vessels serving the liver. Medical details don’t matter; this is just the maguffin to get Marlowe to London and later Vosnia.)

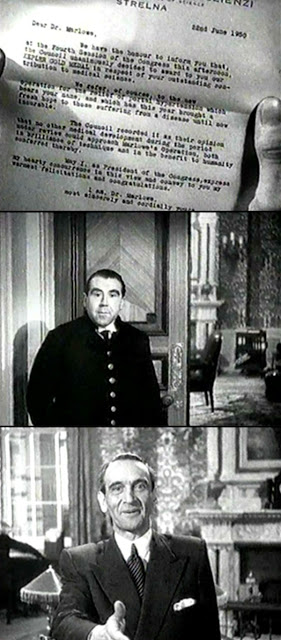

In a 3-minute subjective-camera sequence that Hitchcock would surely have approved, we see through Marlowe’s eyes a letter from the International Congress of Science in Vosnia announcing an award to him for his surgical breakthrough…

…a steward at his London club announcing that “a

gentleman…a foreigner, sir, didn’t quite catch

his name” is waiting to see him…

…and a Vosnian diplomat there to congratulate

Marlowe on his award, and to invite him to

Strelna to receive the award and to demonstrate

his surgical technique. As the first American

recipient of this award, Marlowe’s presence

in Strelna would be a remarkable gesture

of international understanding.

Despite the stated misgivings of some

of his more conservative colleagues,

Marlowe accepts the invitation out of a

spirit of international friendship (mixed,

perhaps, with just a trace of vanity), and

before long he’s on a plane for Strelna.

(Here we get a hint suggesting

approximately when State Secret takes

place — or at least when it was shot:

The magazine in Marlowe’s hands is the

November 12, 1949 issue of The New

Yorker.)

In Strelna Marlowe is wined, dined and feted,

and finally honored at a formal ceremony where

he receives his award from Colonel Galcon, the

urbane and affable Vosnian Minister of Public

Services. As Marlowe learns, that’s not the

only government hat Galcon wears; indeed, he

seems to be General Niva’s right-hand man,

with more official portfolios than Poo-Bah

in Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado.

The next day Marlowe meets and examines the patient on whom he is to perform his operation. The man is a nondescript-looking Eastern European peasant-type — a farmer, perhaps, or laborer. Through an interpreter, Marlowe reassures the man, then scrubs up for the surgery.

But once the operation is well underway, in fact nearly completed —

Marlowe suddenly notices that others in the operating party — his colleague Dr. Revo (Karel Stepanek), the nurse, the anaesthetist — keep glancing nervously at one of the anonymous white-clad figures standing around the table. Looking more closely and scouring his memory, at last it comes to him, and Marlowe is astonished to find himself gazing into the hawk-like eyes of the versatile Col. Galcon.

Why does this supreme government functionary care about the fate of a little Vosnian nobody? His suspicions aroused, Marlowe demands to see the concealed face of the patient — and once again, heightening Marlowe’s worry, everyone looks to Galcon for permission. Galcon nods curtly, and Marlowe at last learns that he is operating not on the man he examined that morning…

…but on General Niva himself!

Containing his anger, Marlowe turns again to his operation and completes the procedure. In the next room, however, Marlowe rages at this gross breach of medical ethics. Galcon is unctuously apologetic. Such a pity that Marlowe recognized the patient; if he hadn’t, he’d be on his way to the airport now, none the wiser. As it is, he simply can’t be allowed to leave…not just yet. Galcon says that at this delicate moment in Vosnian and international politics, no word of Gen. Niva’s illness can be allowed to leak out. Marlowe is in the midst of demanding an immediate car to the airport when the room suddenly reels and all goes black.

Marlowe awakens with “a slight concussion” which Galcon tells him he suffered in “a fall”. The stooge Dr. Revo has prescribed rest, and Marlowe is to aid Revo in monitoring Gen. Niva’s recovery. “I hate insisting when we are so much in your debt,” Galcon says, but “we can save newsprint, which is in short supply, by announcing the General’s illness, his recovery, and your departure at one and the same time.”

In the days that follow, after wiring Marlowe’s London colleagues that the doctor will be staying on in Strelna for several days, Galcon proves to be the most charming and hospitable of captors. One night over billiards Marlowe asks what Galcon would have done if Niva had died on the operating table. If we cannot afford to announce his illness, Galcon replies, how much less could we have acknowledged his death. They couldn’t have let Marlowe go, nor could they have kept him indefinitely. “It would be very difficult to see more than one solution.”

On the very morning that Marlowe is finally to leave for London, the situation he and Galcon discussed over billiards becomes more than hypothetical: Gen. Niva suffers a pulmonary embolism and dies. As Galcon stands in shock over the body of his dead leader, Marlowe gathers his wits and bolts for the airport with his unsuspecting driver.

Galcon soon follows in hot pursuit, but when he catches up with the car Marlowe is gone…

…having taken advantage of a stop at a streetcar crossing to transfer from one conveyance to the other.

Arriving in Strelna and unable to speak the language, Marlowe goes straight to a public telephone arcade and steps into a booth. He asks haltingly for the American legation, and when a voice at the legation answers in English, Marlowe asks to speak with someone in authority. But the instant he gives his name the line goes dead. Switching to another booth and about to try the call again, Marlowe sees that in those few seconds, a cadre of police have arrived and seized the man who stepped into the first booth after Marlowe vacated it. Obviously, a second phone call to the American legation is not such a hot idea.

As the poor man jabbers his innocence, Marlowe slips out of the arcade and seeks refuge in a barber shop. Hanging his coat on the wall, he takes a seat in one barber’s chair and undergoes a shave to avoid attracting attention. As he leaves, he picks up somebody else’s coat, but before he can return it the barber helps him into the coat, the wrong one, and Marlowe acquiesces rather than do anything the barber might remember later.

Marlowe lucks across an English-speaking cab driver who takes him to the American legation, but a street disturbance is going on there; the police are involved, and Marlowe barely escapes being shot as he flees down an alley. We later learn from an English-language radio broadcast that a riot (obviously — to us, at least — staged) broke out that afternoon in front of both the American and British legations. The Vosnian State Police have duly placed guards in front of both offices to ensure that law and order are maintained — and, of course, to intercept Marlowe.

Furtively wandering the streets as sound trucks patrol with announcements that include the word “Amerikani”, and wanted posters with his picture begin appearing everywhere, Marlowe joins a crowd filing into a vaudeville theater (after a close call when a policeman detains another man who slightly resembles Marlowe’s picture). As he slouches in his seat wondering what to do next…

…he is amazed to hear an English voice coming from the stage, singing the old Mills Brothers song “Paper Doll”. It’s clear that the lead singer is bilingual — she slips easily from Vosnian to English and back again in the number — and the card on the easel by the proscenium identifies the act as “Sisters Robinson”.

As Marlowe mulls this, he sees the policeman he barely eluded outside stalking the aisles of the theater. Meanwhile the next act, an escape artist, has evidently called for volunteers from the audience, and when a number of men file backstage Marlowe joins them.

Sneaking upstairs, he finds a party going on in one of the dressing rooms. He also finds the English singer, Lisa Robinson (Glynis Johns). “You are English, aren’t you?” “Fifty percent,” she says. “We don’t see many Americans in Strelna. What are you doing here?” “Running from the police.” Stunned, Lisa flies into a hissing-whisper panic. “Do you think I’m mad? I can’t help you! Get out of here!”

Downstairs, that cop is showing Marlowe’s picture around to the vaudevillians backstage. Marlowe sidles out the stage door and muscles his way into a car with Lisa and several of her friends — none of whom, fortunately, can understand their conversation. Marlowe’s obvious desperation and Lisa’s essential decency overcome her fear, and she smuggles him into her room at her boarding house, while the other two girls in her act leer. Lisa allows Marlowe to sleep on her sofa (“What will your sisters think?” “They’re not my sisters and they have nothing to think with.”), but he will have to be on his way in the morning.

When Marlowe wakes next morning, Lisa has a gun on him and addresses him in Vosnian. In English, she tells him to stop pretending not to understand: She knows that his name is Karl Theodor, he’s a smuggler of foreign currency, and he’s flying to London tonight. Lisa went through Marlowe’s jacket while he slept — the wrong one, that is, the one he picked up in the barber shop — and found “his” ID card, plane ticket, and 5,000 U.S. dollars. Marlowe tries to explain but she doesn’t believe him.

But then one of Lisa’s neighbors spots Marlowe in her room and recognizes him from the picture the cop showed him last night. Lisa overhears the neighbor calling the police and realizes Marlowe really is the American they’re looking for, so the two of them abscond out the back door. Hiding in a movie theater, he finally whispers the whole story to her. Now that she’s been linked with Marlowe, they’re both as good as dead if Marlowe is caught. Unable to reach the American or British legations, their only hope is somehow to get out of the country. And their only lead is the man Theodor, who was about to leave for London.

Since the purloined jacket contains Theodor’s keys as well as his address, the two are able to let themselves in to his apartment. When Theodor (Herbert Lom) comes home, he is alarmed, but actually relieved when he learns they’re “only” there to blackmail him; at least they’re not from the police, what with possessing foreign currency being a hanging offense in Vosnia.

But Theodor isn’t flying to London tonight, and neither is anybody else. All planes have been grounded, and Theodor recognizes Marlowe as a wanted man, although he doesn’t know why. So, taking a gamble, Marlowe tells him about Niva’s death. Horrified, Theodor realizes that he’s as dead as Marlowe and Lisa if the two don’t get out of the country, so he has no choice but to help them — and to foot the bill for any bribes that will need to be paid. Grumbling all the way, he smuggles them in the dead of night onto a friend’s lake barge. They are to disembark in the town of Bilin on the opposite shore and take the tramway up the mountain to a man named Sigrist, who will escort them over the mountains to the frontier. “Next time I have my hair cut,” Theodor mutters, “I’ll make a point of keeping on my jacket.”

By now Lisa is wanted too, and her picture is as widespread as Marlowe’s. On the tramway, the two even spot her on the front page of a newspaper the motorman is reading.

They position themselves to hide the picture from other passengers, and they chat up the motorman to keep him from turning the page. They try to find a way to swipe the paper when he’s not looking, but it’s no use…

…and the motorman finally sees the picture on his return trip downhill. The slow downward trip buys Marlowe and Lisa a little time…

…but the motorman wastes no time reporting the sighting to police when he finally gets back to the station.

Sigrist, a hardy mountaineer who asks no questions and answers none (“You want to get out, we’re being paid to take you.”), leads Marlowe and Lisa over the treacherous mountains (“The easy ways are always guarded.”). But the motorman’s warning has galvanized Vosnia’s ever-efficient state police; Col. Galcon himself is on his way to spearhead the search, and soldiers have begun swarming the passes.

One of them spots Sigrist in the lead and shoots him off the mountain; only a snapping rope saves Marlowe and Lisa from following Sigrist’s body down the rocky cliff.

Lisa momentarily panics, but Marlowe urges her to pull herself together, and she does. They continue inching their way along the narrow ledge…

…only to come face to face with the soldier who shot Sigrist. In a brief, desperate struggle, Marlowe overcomes the soldier and (with Lisa as interpreter) orders him to lead them to the frontier.

Finally they come to an outcrop overlooking a small cluster of buildings below. That’s the frontier, the soldier tells them. Marlowe knocks the soldier out, and he and Lisa run down the hill toward freedom.

But they are not at the frontier; the soldier has led them into a trap. They try to flee, but Lisa is shot, and both of them are captured.

The screen ripples, and we are reminded of what we’ve forgotten in all the excitement: This has all been a flashback. Now we end as we began, with the harried and bedraggled Dr. John Marlowe helpless in the clutches of the suavely implacable Col. Galcon, as they listen on the radio to the “spontaneous” demonstration of adoration for General Niva. But now we know that the Niva we saw on the balcony at the beginning of the picture wasn’t Niva at all; he was already dead by then. The man on the balcony, Galcon admits, is a double, a stand-in for the General until the results of the forthcoming (rigged) election can give the government a mandate for “extreme security measures”. We also know who the bedridden woman in the next room is. Marlowe has saved Lisa’s life — but, as Galcon says, to little purpose; both of them are only minutes away from being murdered on Galcon’s orders.

Let’s leave it at that for now, shall we? State Secret is a tight, nifty little thriller that gives Douglas Fairbanks Jr. one of his best roles ever — certainly his best since Rupert of Hentzau in The Prisoner of Zenda (’37). And it deploys elements that Hitchcock had made his own. The everyman, fish-out-of-water hero — a noted surgeon in this case, perhaps, but certainly ill-equipped for such desperate cloak-and-dagger stuff. The skeptical and reluctant bystander dragooned into helping the hero who moves from hostility to sympathy and winds up just as deep in the soup as he is. The urbane, even charming villain who in other circumstances would be a delightful companion for an evening of chess, cigars and fine brandy.

Jack Hawkins and Glynis Johns shine here, of course

(didn’t they always, and doesn’t Glynis still?), but the

one whom Variety aptly dubbed the “picture stealer”

is Herbert Lom as Karl Theodor, a slippery, weasely

little black-marketeer reminiscent of Peter Lorre at

his most Ugarte-esque. Lom steals the picture all

right, something he did more than once (check him

out sometime as Napoleon in King Vidor’s War and

Peace; he steals that one too). I’m delighted to

report that Lom, who was born Herbert Charles

Angelo Kuchacevich von Schluderpacheru in the

Austro-Hungarian Empire during World War I,

is still with us, and will turn 95 on September 11.

Continued long life to him, and to Glynis Johns,

also still with us.

Making State Secret entailed another challenge that surely would have piqued Alfred Hitchcock’s interest. Fully a quarter — maybe even a third — of the picture is spoken (or, in the vaudeville scenes, sung) in “Vosnian”, a language that doesn’t exist and was concocted for Sidney Gilliat by one Georgina Shield (“language advisor” in the credits). The sound of Vosnian is vaguely Slavic, vaguely Russian, and vaguely German — sometimes by turns, sometimes all at once. There are no subtitles in the movie — meaning that whenever the actors speak Vosnian, they are saying things no one on Earth except Georgina Shield could possibly understand. Yet there are two salient points to be made here: (1) while the exact words are largely unknown, it is always crystal clear what the characters are saying; and (2) every actor in the picture, from Jack Hawkins and Glynis Johns all the way down to the barber who gives John Marlowe his shave, seems absolutely to be speaking his or her native tongue. It’s a remarkable touch that reflects well on both director and actors — and one that, in the overall suspense and pace of the picture, is liable to go unnoticed.

Oh, and one final note: In Sweden, State Secret played under the title Hemlig Operation, which translates to Covert Operation. What a clever title that is, even in English!

* * *

Epilogue: Spoiler-phobes read no farther

Marlowe trudges away from his last meeting with Galcon, being led to the spot where his “shooting accident” will be carefully staged. He hears — no doubt believing it will be the last thing he hears — the sound on Galcon’s radio of the crowd outside the People’s Palace in Strelna, wildly cheering and chanting “Ni-va! Ni-va! Ni-va!”

Suddenly there’s a gunshot, then four more in rapid succession. Marlowe flinches, but the shots weren’t from the guards facing him — they came from the radio. The cheering and chanting from the crowd changes to screams and pandemonium. Then the radio goes dead.

Marlowe runs back to the door of the cottage. Galcon is already on the phone to Strelna, barking questions in Vosnian. He blanches. General Niva — or rather, “General Niva” — has been shot. Killed instantly. In full view of 50,000 of his subjects.

What now? asks Marlowe. Who knows? says Galcon. “At the moment I don’t know whether I’m a crypto-fascist, a liberal humanitarian, or a simple deviationist. Depends whether I still control tomorrow’s newspapers.”

Oh yes, Galcon still has to deal with Marlowe and Lisa. He orders a stretcher party to escort the two of them to the frontier, where there’s an excellent hospital for Lisa on the other side. Yes, they’re free to go. What can either of them say? Only that a dead man is dead.

At the door Galcon turns and delivers what must surely be one of the unsung great exit speeches. “Please don’t think that I am being in any way whimsical, but if you should happen to hear of a vacant chair for political science — anywhere — try to get in touch with me.” “That may be a little difficult,” says Marlowe. Galcon smiles. “It may be difficult, but I would appreciate the effort.” And he is gone.

Later, on their long-deferred flight to London, Lisa — now almost fully recovered from her wound — lays down the law to Marlowe. The only reason she is accepting his help is that he really does owe her something. Once she is on her feet, they will part. They have absolutely nothing in common. It would be humiliating for her and disastrous for him. Marlowe nods and agrees with everything she says. She eyes him suspiciously. You don’t mean a word you say, she accuses him. No, Marlowe admits, he doesn’t.

But it’s all right. Neither does she.

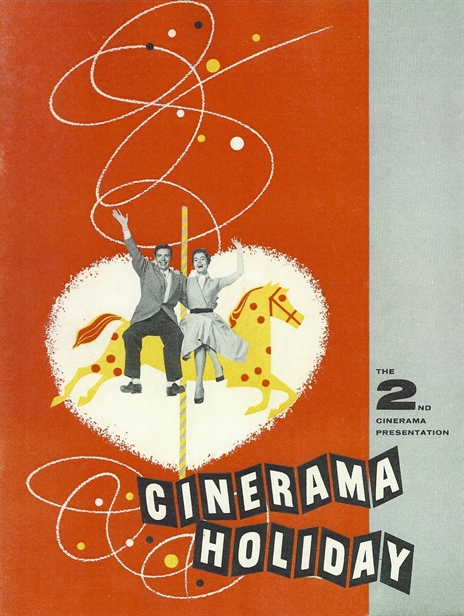

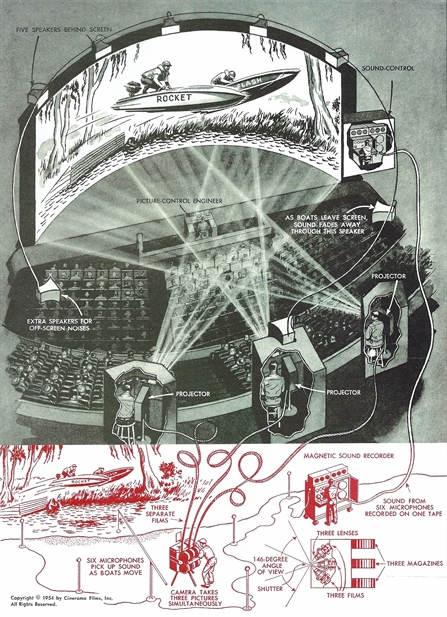

By the early ’50s things had changed — and besides, Cinerama was as different from those early pictures in Grandeur and Magnascope as FM radio was from AM. The screen wasn’t just wide, it was vast, curved 146 degrees to match almost the full range of human vision, using three synchronized projectors to display an image nearly five times the size of even the largest theater screen. And Cinerama had a multi-channel high-fidelity sound system for which a new term was coined: “stereophonic sound”.

By the early ’50s things had changed — and besides, Cinerama was as different from those early pictures in Grandeur and Magnascope as FM radio was from AM. The screen wasn’t just wide, it was vast, curved 146 degrees to match almost the full range of human vision, using three synchronized projectors to display an image nearly five times the size of even the largest theater screen. And Cinerama had a multi-channel high-fidelity sound system for which a new term was coined: “stereophonic sound”. This coming September 30 will mark the 60th anniversary of Cinerama‘s premiere, and the occasion is not going unobserved. ArcLight Cinemas, which owns the Pacific Cinerama Dome in Hollywood (one of only three theaters in the world equipped to show true Cinerama) will be spending a week, from September 28 to October 4, presenting — to borrow the title of the second Cinerama production — a Cinerama Holiday. Every single Cinerama picture produced during the years Cinerama reigned as the Metropolitan Opera of movies will be on display, along with a couple of ringers — Cinerama’s Russian Adventure, an Americanized release of a picture produced by the Soviets in 1958 with pirated equipment and called Kinopanorama (then, typically of the time, the Russians accused us of stealing it from them); and Windjammer: The Voyage of the Christian Radich (1958), produced in a competing but compatible process called Cinemiracle — plus two movies that bore the Cinerama name even though they weren’t: It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (’64) and 2001: A Space Odyssey (’68).

This coming September 30 will mark the 60th anniversary of Cinerama‘s premiere, and the occasion is not going unobserved. ArcLight Cinemas, which owns the Pacific Cinerama Dome in Hollywood (one of only three theaters in the world equipped to show true Cinerama) will be spending a week, from September 28 to October 4, presenting — to borrow the title of the second Cinerama production — a Cinerama Holiday. Every single Cinerama picture produced during the years Cinerama reigned as the Metropolitan Opera of movies will be on display, along with a couple of ringers — Cinerama’s Russian Adventure, an Americanized release of a picture produced by the Soviets in 1958 with pirated equipment and called Kinopanorama (then, typically of the time, the Russians accused us of stealing it from them); and Windjammer: The Voyage of the Christian Radich (1958), produced in a competing but compatible process called Cinemiracle — plus two movies that bore the Cinerama name even though they weren’t: It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (’64) and 2001: A Space Odyssey (’68).