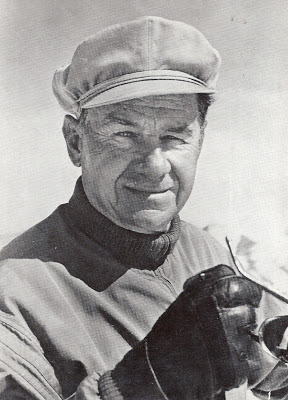

In his 1977 memoir

So Long Until Tomorrow, the 85-year-old Lowell Thomas — with nearly a quarter-century of frustrated hindsight — remembered the Stanley Warner deal thus:

“Our original group of founders had dwindled — Fred Waller, the gentle, bespectacled genius who started it all, had died before he even knew of his triumph; Mike Todd was busily hustling and working with American Optical on the process to be called Todd A-O … Arrayed against [Frank Smith], Merian Cooper and me were men of wealth who had gone into Cinerama solely for the investment possibilities, and at this critical juncture, either unwilling to go looking for the additional cash or simply ready to take their already large profits, they opted to sell out.

“The buyer was the Stanley-Warner company, and from a purely practical viewpoint, maybe the decision was not all wrong. In making it we all made a lot of money. But the bells began tolling for Cinerama then and there. Stanley-Warner was a brassiere manufacturing corporation, plus owners of a major theater chain. But they were not film producers … They didn’t really know what Cinerama was all about.”

Thomas’s memory wasn’t flawless. “Stanley Warner” wasn’t hyphenated, and “Todd-AO” was. Fred Waller lived long enough to know his triumph and collect an Oscar for it; he died in May 1954, nine months after the Stanley Warner deal was approved by the court. And Stanley Warner wasn’t “a brassiere manufacturing company”. Not yet. They didn’t purchase the International Latex Corporation (maker of, among other things, the Playtex Living Bra) until April 1954, a year after buying their six-year control of Cinerama Productions Corp. (This expansion from theater operation to ladies’ undies and baby pants was an early example of the kind of diversification that ultimately led to the entertainment conglomerates of today.)

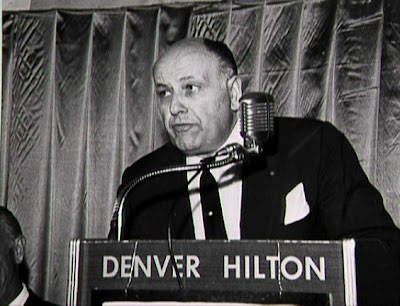

But Thomas’s basic point was well taken. The folks at Stanley Warner, it’s true, were not film producers. And despite S.H. Fabian’s advocacy of alternate entertainment technologies — he was an early proponent of drive-in theaters, 3-D, and closed-circuit theatrical television — he really didn’t know what Cinerama was all about. Even if nobody heard it at the time, the bells were definitely tolling.

Thomas can be forgiven a certain amount of bitterness. By May 1954, Stanley Warner had managed to open only seven new Cinerama theaters and had yet to complete a follow-up feature to This Is Cinerama; yet they had managed to scrape up $15 million ($166.18 million in 2022) to buy International Latex. Moreover, in the next four years SW would lavish far more care and resources on International Latex, where profit margins were high and they were not under the thumb of the U.S. Justice Dept. Small wonder that, decades later, Thomas remembered SW being already in the brassiere business when Cinerama came along.

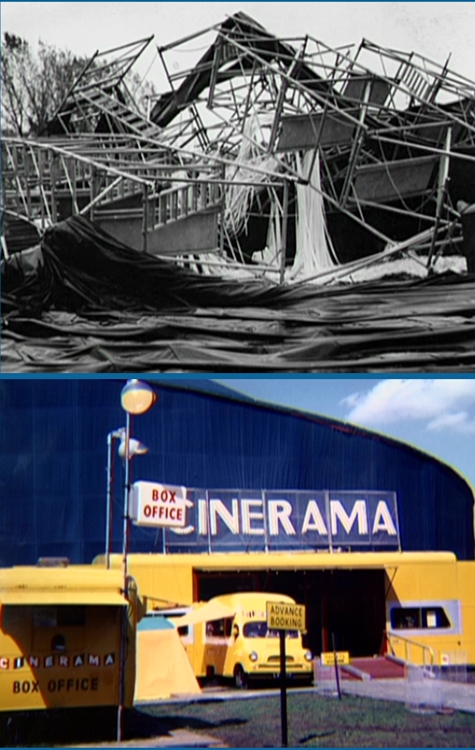

Stanley Warner was contractually obligated to produce a picture within the first year, and their original plan was the same as Cinerama’s before them: to involve one of the major studios in making Cinerama pictures. In early August, even before the court approved the buyout, talks were held with Columbia, Paramount and Warner Bros. All came to nothing, including a proposed picture about the Lewis and Clark expedition to star Gregory Peck and Clark Gable as the great explorers (excellent casting, that).

With the success of The Robe, studios began stampeding to CinemaScope in preference to the more expensive Cinerama, and any chance of a deal in that direction evaporated. SW negotiated with Merian Cooper, who was thinking of molding Paul Mantz’s 200,000 feet of aerial footage into a picture to be called Seven Wonders of the World, but talks broke down when they couldn’t agree on a completion schedule.

So Stanley Warner turned to producer Louis de Rochemont, who had experience in both documentary (We Are the Marines, the March of Time newsreel shorts) and fiction filmmaking (The House on 92nd Street, Boomerang!). De Rochemont had an idea that combined the two: follow one pair of American newlyweds as they honeymooned in Europe, and another European pair as they honeymooned across America. The Thrill of Your Life began shooting in December 1953 with John and Betty Marsh of Kansas City, Mo. and Fred and Beatrice Troller of Zurich, Switzerland touring the Cineramic stops on their respective honeymoon tours. Production wrapped in June ’54 and, with the title changed to Cinerama Holiday, the picture was ready for release by the August deadline.

But Stanley Warner held off on releasing Holiday. By this time there were 11 Cinerama theaters in operation, and This Is Cinerama was still playing to sold-out houses everywhere — even in New York, where it was nearly two years old. Why cut a thriving box office short when there was still a lot of money to be made?

And here’s where Cinerama’s can of corporate worms came home to roost — if you’ll forgive a mixed metaphor. At one end of the corporate arrangement was Vitarama and Cinerama Inc.; at the other end was Cinerama Productions — now a mere holding company for Stanley Warner Cinerama, but with its own stockholders. And in between was Stanley Warner.

Cinerama Inc. made most of its money from the equipping of Cinerama theaters — the sale or lease of equipment and supplying of replacement parts — and was annoyed that Stanley Warner wasn’t opening theaters at a quicker pace. The remaining investors in Cinerama Productions were annoyed that SW wasn’t opening more theaters

and producing a steadier stream of pictures to show in them. And Stanley Warner, who had to put up

all the money for both the theaters and the pictures but had to share almost half of any profits (when operating costs alone could eat up as much as 90 percent of gross ticket sales), was beginning to wonder if investing in the process had been such a good idea in the first place. The cracks among the partners in Cinerama were beginning to show, and were the subject of chatter in the trade press.

The general public, however, saw none of this. All they knew, if they hadn’t seen This Is Cinerama yet, was that Cinerama was the miraculous more-than-a-movie that everybody was talking about. If they had seen it, all they knew was that the theater was jam-packed, at top-dollar prices; if they saw it more than once, showing that their own enthusiasm hadn’t dimmed, they saw that nobody else’s had either. And when Cinerama Holiday finally opened in February 1955, the box office didn’t fall off a dime. Movie houses in towns or neighborhoods may bring in picture after picture in CinemaScope, but to the public Cinerama was the gold standard. More than a movie, indeed — it was a tourist attraction.

There had been talk of plans to expand Cinerama into foreign countries almost from the first opening in September 1952, but nothing had ever come of that idea. In the spring of 1954, Stanley Warner sought to farm out the foreign exhibition rights — find somebody who would foot the bill for overseas expansion

and pay SW for the privilege. After three months of negotiations, S.H. Fabian hammered out a deal with Nicolas Reisini, president of Robin International.

Neither Robin International nor the Greek-born Reisini had any experience in the movie business. Robin International was reportedly an import/export company, although exactly what it imported and exported wasn’t clear. Nothing shady, mind you, it’s just that Reisini seems to have had his fingers in a bewildering number of pies — none of them having anything to do with the movie industry.

But there was another factor. According to his son Andrew (interviewed for David Strohmaier’s 2002 documentary Cinerama Adventure), Nicolas Reisini as a young man had seen the Paris premiere of Abel Gance’s Napoleon in 1927 and been spellbound — especially by Gance’s three-screen “Polyvision” triptych that climaxed the picture. When Reisini saw This Is Cinerama in New York in late ’52 or early ’53, it revived that youthful excitement and seemed to be the fulfillment of Gance’s earlier vision. Son Andrew says Reisini decided on the spot that he wanted to get in on Cinerama one way or another, and when Stanley Warner went looking for someone to buy foreign rights, Reisini was ready.

Reisini’s deal, announced in July 1954, licensed him to establish Cinerama theaters in any five cities (later amended to six) outside the western hemisphere. He ponied up a deposit of $500,000, to be refunded $100,000 at a time for each new theater as it opened. Robin International was responsible for all the expenses of converting and operating the theaters. And with this agreement, yet another corporation was added to the cluster of those already in place, each straining for its share of the trickle of profits that remained after Cinerama’s sky-high operating costs.

As things turned out, the first foreign showing of Cinerama — outside North America, that is; theaters in Toronto, Montreal and later Vancouver were considered “domestic” — wasn’t a permanent installation. It was in September ’54 at an international trade show in Damascus, Syria. This Is Cinerama was a huge success there, and again later that year at another fair in Bangkok, Thailand — where it was such a hit that it was held over an additional two weeks after the fair closed. (It was the Soviet Union’s fury at being upstaged in Damascus that led them to pirate their own three-screen process, which they called Kinopanorama. They couldn’t even come up with an original name for it.)

Robin International’s first “permanent” theater was the Casino in London, opening October 1, 1954. Reisini reduced his own expenses by sub-licensing to local exhibitor companies in each country, letting them shoulder the cost of converting and equipping the theater (more corporations, more straining for ever-thinning profits). That’s how it went when theaters opened in Japan (Tokyo and Osaka, January ’55), Italy (Milan, April ’55; and Rome, in May) and France (Paris, May ’55).

Meanwhile, back home, Stanley Warner and Louis de Rochemont had fallen out over money — and SW’s reluctance to invest in perfecting the Cinerama process. De Rochemont stalked off to produce

Windjammer: The Voyage of the Christian Radich in CineMiracle (a competing process just different enough to avoid infringing Cinerama’s patents). SW had enticed Lowell Thomas back to produce

Seven Wonders of the World (revived after the departure of Merian Cooper). Shooting wrapped in June ’55, but as with

This Is Cinerama before it,

Cinerama Holiday was drawing so strongly that SW was in no hurry to release

Seven Wonders (it finally opened in April 1956).

Buz Reeves at Cinerama Inc. finally lost patience with Stanley Warner’s dilatory production schedule. He charged SW with breach of contract and announced that Cinerama Inc. would produce its own picture, a documentary about the peaceful uses of atomic energy to be called The Eighth Day. But Reeves didn’t really have any leverage; any production would still be dependent on SW for theaters to show it in. The Eighth Day staggered along for over three years at a cost of $439,688 before being written off. (The Cinerama camera reportedly filmed the last above-ground nuclear test during this period, but the footage has mysteriously disappeared. Wouldn’t that be a sight to see!)

In the interim, Stanley Warner had produced two more travelogues, another one with Lowell Thomas (Search for Paradise, about India and the Himalayas), September ’57; and South Seas Adventure with producer Carl Dudley, narrated by Orson Welles, July ’58.

And with that the Stanley Warner era at Cinerama came to a close, after four pictures in five years. (For the record, in that same time 20th Century Fox and the other Hollywood studios had produced 291 pictures in CinemaScope.) When the dust from the transition settled, the new big cheese at Cinerama Inc. was none other than our starry-eyed friend Nicolas Reisini. He was an adroit wheeler-dealer who loved Cinerama and had a genuine vision for the process, and he would accomplish things that nobody before him had been able to do. But he would also fall victim to Cinerama’s chronic cash-flow problems, and in the end he presided over the process’s march into oblivion.

I’ll get into that next time, then I’ll add a brief coda about the mechanics of Cinerama, and efforts to perfect Fred Waller’s revolutionary invention.

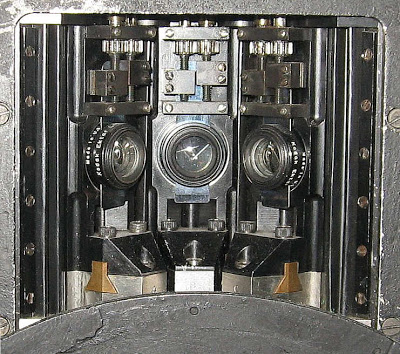

Some of Cinerama’s technical problems can be discerned in this frame (frames, actually) from Search for Paradise — although to be fair, by the time this picture was shot most of them had been considerably alleviated. Most often complained about were those dividing lines between the three panels. The panels overlapped by a degree or two, which meant that the overlap area would inevitably get the light from two projectors. To minimize this over-exposure, the sides of each projector’s film gate were supplied with little devices called (spellings vary) “gigolos”. These were serrated, comb-like assemblies mounted on cams that moved them up and down, once for each frame (i.e., 26 times per second) as the film passed through the gate. This was intended to cut down on the excess light hitting the overlap, and to blur the sharp division from one panel to the next. As a matter of fact, this worked reasonably well.

Some of Cinerama’s technical problems can be discerned in this frame (frames, actually) from Search for Paradise — although to be fair, by the time this picture was shot most of them had been considerably alleviated. Most often complained about were those dividing lines between the three panels. The panels overlapped by a degree or two, which meant that the overlap area would inevitably get the light from two projectors. To minimize this over-exposure, the sides of each projector’s film gate were supplied with little devices called (spellings vary) “gigolos”. These were serrated, comb-like assemblies mounted on cams that moved them up and down, once for each frame (i.e., 26 times per second) as the film passed through the gate. This was intended to cut down on the excess light hitting the overlap, and to blur the sharp division from one panel to the next. As a matter of fact, this worked reasonably well.

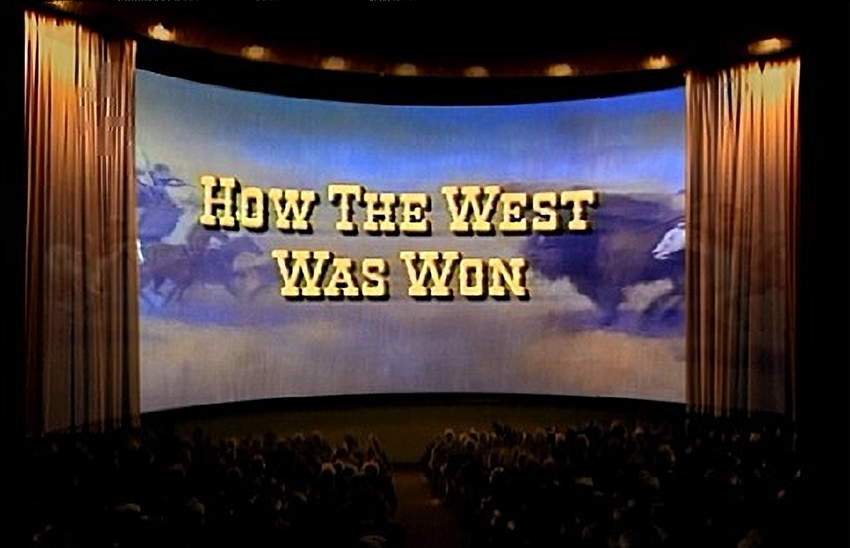

Most noticeable of all was the parallax effect caused by the fact that the Cinerama camera was really three cameras, each with its own vanishing point. (“parallax [pár-a-laks] n. 1 the apparent difference in the position or direction of an object caused when the observer’s position is changed.”) Imagine yourself looking out at a vista: First you look straight ahead; then you take a step to your right and turn your head left; then two steps left and turn your head right. You’re looking at the same view each time, but from three ever-so-slightly different places. That’s parallax. Take this frame on the right, from the last scene of How the West Was Won, flying under the Golden Gate Bridge. The join lines and the difference in color textures from one panel to the next are glaringly obvious, but even more pronounced are the “elbows” in the bridge; everyone knows that the Golden Gate travels in a perfectly straght line between San Francisco on the left and Marin County on the right.

Most noticeable of all was the parallax effect caused by the fact that the Cinerama camera was really three cameras, each with its own vanishing point. (“parallax [pár-a-laks] n. 1 the apparent difference in the position or direction of an object caused when the observer’s position is changed.”) Imagine yourself looking out at a vista: First you look straight ahead; then you take a step to your right and turn your head left; then two steps left and turn your head right. You’re looking at the same view each time, but from three ever-so-slightly different places. That’s parallax. Take this frame on the right, from the last scene of How the West Was Won, flying under the Golden Gate Bridge. The join lines and the difference in color textures from one panel to the next are glaringly obvious, but even more pronounced are the “elbows” in the bridge; everyone knows that the Golden Gate travels in a perfectly straght line between San Francisco on the left and Marin County on the right.

Reeves’s proven management skills might have turned Cinerama around even then if he had taken the reins in a firm hand, but evidently that was never his intention. With hindsight, it appears that Reeves was simply tired of dealing with Cinerama; his concerted efforts to streamline Cinerama’s corporate structure may have been just a way of getting it in good order — like a real-estate speculator fixing up and flipping a rundown house — so he could sell it and roll the capital into his own company, Reeves Soundcraft. In any event, Reeves had control of Cinerama for less than a year before he put it on the market — negotiating first with Walter Reade Jr. of Reade Theatres, then with Nicolas Reisini of Robin International. In the end Reisini bought Reeves out, becoming president and CEO of Cinerama Inc. (In his history of Cinerama, Thomas Erffmeyer mentions that in 1947 Reisini had purchased a California asbestos mine for $350,000 — which now, in 1959, he sold for $4 million. Dr. Erffmeyer doesn’t say if it was this windfall which enabled Reisini to buy Cinerama Inc., but it strikes me as a logical inference.)

Reeves’s proven management skills might have turned Cinerama around even then if he had taken the reins in a firm hand, but evidently that was never his intention. With hindsight, it appears that Reeves was simply tired of dealing with Cinerama; his concerted efforts to streamline Cinerama’s corporate structure may have been just a way of getting it in good order — like a real-estate speculator fixing up and flipping a rundown house — so he could sell it and roll the capital into his own company, Reeves Soundcraft. In any event, Reeves had control of Cinerama for less than a year before he put it on the market — negotiating first with Walter Reade Jr. of Reade Theatres, then with Nicolas Reisini of Robin International. In the end Reisini bought Reeves out, becoming president and CEO of Cinerama Inc. (In his history of Cinerama, Thomas Erffmeyer mentions that in 1947 Reisini had purchased a California asbestos mine for $350,000 — which now, in 1959, he sold for $4 million. Dr. Erffmeyer doesn’t say if it was this windfall which enabled Reisini to buy Cinerama Inc., but it strikes me as a logical inference.)

Cinerama Inc. made most of its money from the equipping of Cinerama theaters — the sale or lease of equipment and supplying of replacement parts — and was annoyed that Stanley Warner wasn’t opening theaters at a quicker pace. The remaining investors in Cinerama Productions were annoyed that SW wasn’t opening more theaters and producing a steadier stream of pictures to show in them. And Stanley Warner, who had to put up all the money for both the theaters and the pictures but had to share almost half of any profits (when operating costs alone could eat up as much as 90 percent of gross ticket sales), was beginning to wonder if investing in the process had been such a good idea in the first place. The cracks among the partners in Cinerama were beginning to show, and were the subject of chatter in the trade press.

Cinerama Inc. made most of its money from the equipping of Cinerama theaters — the sale or lease of equipment and supplying of replacement parts — and was annoyed that Stanley Warner wasn’t opening theaters at a quicker pace. The remaining investors in Cinerama Productions were annoyed that SW wasn’t opening more theaters and producing a steadier stream of pictures to show in them. And Stanley Warner, who had to put up all the money for both the theaters and the pictures but had to share almost half of any profits (when operating costs alone could eat up as much as 90 percent of gross ticket sales), was beginning to wonder if investing in the process had been such a good idea in the first place. The cracks among the partners in Cinerama were beginning to show, and were the subject of chatter in the trade press. There had been talk of plans to expand Cinerama into foreign countries almost from the first opening in September 1952, but nothing had ever come of that idea. In the spring of 1954, Stanley Warner sought to farm out the foreign exhibition rights — find somebody who would foot the bill for overseas expansion and pay SW for the privilege. After three months of negotiations, S.H. Fabian hammered out a deal with Nicolas Reisini, president of Robin International.

There had been talk of plans to expand Cinerama into foreign countries almost from the first opening in September 1952, but nothing had ever come of that idea. In the spring of 1954, Stanley Warner sought to farm out the foreign exhibition rights — find somebody who would foot the bill for overseas expansion and pay SW for the privilege. After three months of negotiations, S.H. Fabian hammered out a deal with Nicolas Reisini, president of Robin International.