Cinedrome celebrates the “Golden Age of Hollywood”, but like many ages, that one has no precise boundary date. As a general rule, I set the end of the Golden Age around 1964 — because that was the last year when the Oscar for best picture went to a movie (My Fair Lady) that was produced entirely within the walls of a major Hollywood studio (Warner Bros.). On the other hand, it’s a hard rule indeed that allows no exceptions, and I’m making an exception now. Here’s why:

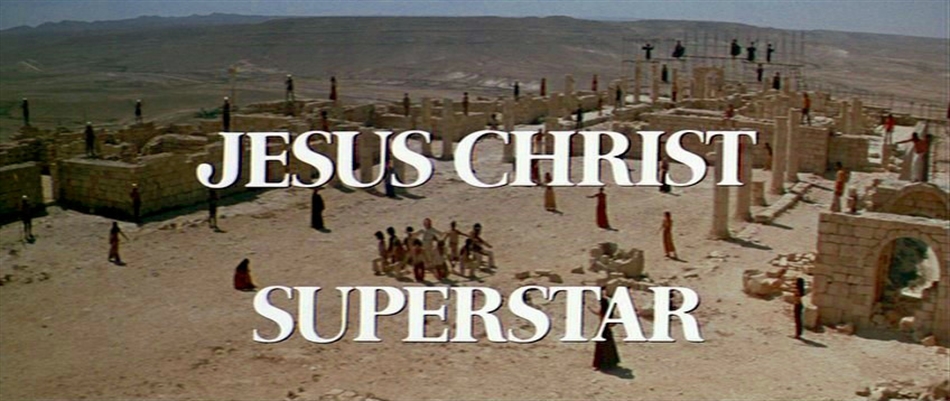

Director Norman Jewison’s 1973 Jesus Christ Superstar is one of the great movie musicals — arguably the last great musical before the genre went into a 30-year hibernation brought on by the collapse of the studio system, rising costs, flagging interest, and the passing from the scene, through death or retirement, of many of its best creators — the Arthur Freeds and Roger Edenses, the Busby Berkeleys and Vincente Minnellis, the Harry Warrens, Irving Berlins and Cole Porters.

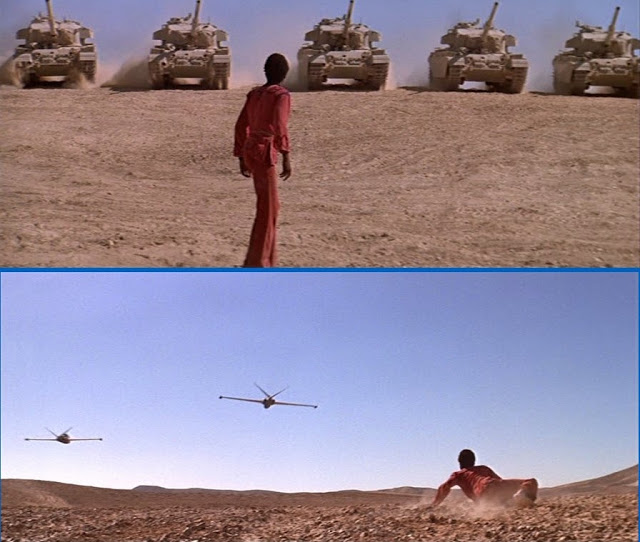

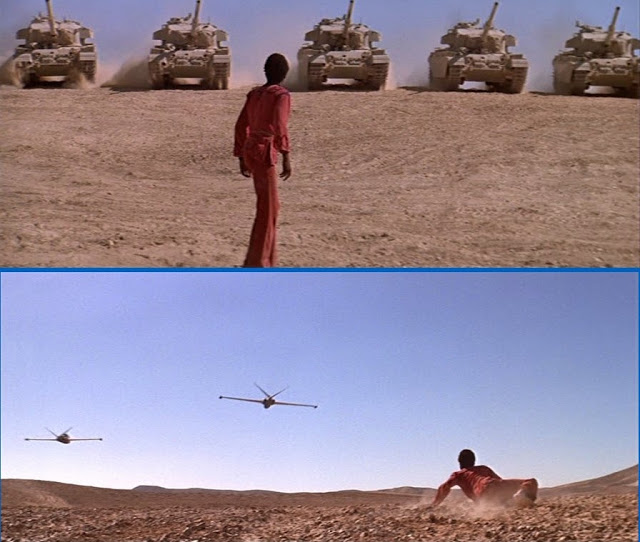

I first saw Jesus Christ Superstar on June 30, 1973, and I wasn’t expecting much. It had been two years since the original concept album by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice had made such an enormous splash, and the ripples had largely subsided; for me, at least, much of its novelty had worn off. Then came the Broadway production, directed by Tom O’Horgan, who had shaken up the Street four years earlier with Hair. From what I saw of O’Horgan’s Superstar in magazines and read in reviews, it sounded pretentious, bloated, glam-campy and tasteless. (Lloyd Webber and Rice reportedly weren’t too pleased with it, and saw to it that things were done differently when the show was staged in London’s West End.) When the movie’s trailer began playing in theaters, with its tanks and jet fighters, I wasn’t impressed; I thought this picture was going to be a stinker, and I wasn’t shy about saying so.

Wrong. As the picture unrolled on the screen before me I was bowled over time and again. At the fadeout I sat there stunned. My friend Paul, who had talked me into seeing it with him, turned to me and said tentatively, almost apologetically, “I thought it was pretty good, Jim.” I said, “I thought it was terrific, Paul.” This being the Era of Continuous Showings, we stayed and sat through the picture again. The next day I returned with other friends and saw it two more times.

As Andrew Lloyd Webber’s overture begins, Jesus Christ Superstar opens with the camera prowling among the ruins of the ancient city of Avdat, in Israel’s Negev Desert 30 miles south of Beersheba. Two thousand years ago this was an important stop on the Incense Road between India and Ceylon in the east and the Mediterranean Sea in the west; today it’s a crumbling wreck. As the camera glides among the pitted walls and topless columns, the only trace of modernity is a temporary scaffold maybe 30 feet high — put there by some team of archaeologists, perhaps — and the only sign of life is a small lizard skittering across a wall in front of our eyes. Suddenly, in the distance, a cloud of dust — coming from what we see is a red, white and turquoise Israeli school bus barreling along the unpaved roads. The bus screeches to a halt at the foot of the hill where Avdat sits, and out springs a ragtag band of hippies, dozens of them. They swarm over the bus like bees in a hive, shaking the sand from the tarps that cover the baggage on the roof, opening the large wicker baskets underneath, tossing down a confusing array of props, costumes, headdresses — and, very carefully, one large wooden cross. These hippies, we see, are a troupe of itinerant street performers; we sense that not one of them has ever seen the inside of a real theater. (In real life, every one of them had. In fact, two of them — Robert LuPone and Baayork Lee — would go on to create the roles of Zach and Connie, respectively, in the original production of A Chorus Line, and Lee would restage Michael Bennett’s choreography for the 2006 revival.) There’s an air of high spirits and camaraderie among the players — they cheerfully help one another into their gear, kiss each other on the cheek, then move on to the next chore. Gradually their excitement settles down, a feeling of ritual and purposefulness begins to grow among them, their movements become deliberate and stylized. Each one slips into his or her character, steps into his or her place, and they assume the tableau you see at the beginning of this post. They are ready to enact their own version of The Greatest Story Ever Told.

This show-within-the-movie approach was the inspiration of Melvin Bragg, who co-wrote the screenplay with director Norman Jewison, after a false start by Tim Rice. “I was asked to do a screenplay,” Rice remembered years later. “I thought great, fantastic…I wrote a screenplay rather like Ben-Hur; you know, Jesus addresses 20,000 people, or armies of Romans steam in from the left. I think they took one look at that and thought, ‘No, that’s gonna be $50 million, forget it.’ My screenplay was instantly ditched, and Melvin Bragg — Lord Bragg — came in and wrote a screenplay.”

Bragg, the celebrated broadcaster, author and polymath who was made Baron Bragg of Wigton, County Cumbria in 1998, saw at once what Rice did not: that the cast-of-thousands Ben-Hur approach was not only prohibitively expensive but incompatible with the pop vernacular of Rice’s libretto for Superstar. Instead, Bragg and Jewison established the framework of the traveling band of players reconstructing the last seven days of the earthly life of Jesus in a tell-us-now-in-your-own-words manner, as if this modern Passion Play had been developed in improvisational workshops before being brought out to be performed in the open air. It is, in effect, an intimate Biblical spectacle in modern dress. In 1973, you could have left the theater after seeing the movie and, before you’d gone two blocks, seen a dozen people dressed exactly like the performers in Superstar — even the Roman soldiers in their purple tank tops and camouflage pants.

In his 2004 commentary on the DVD, Jewison credits production designer Richard Macdonald with the decision to shoot the picture on existing locations, making only minor modifications in the form of set dressing. Most of these locations — Avdat, King Herod’s Palace, the amphitheater at Beit She’an near Nazareth, where Jesus (Ted Neeley) is tried and condemned by Pontius Pilate (Barry Dennen) — were the ruined remains of Ancient Rome’s occupation of Palestine under the Caesars. Choosing to shoot in these places was a transformative decision, for it meant that Jesus Christ Superstar would show the early followers of Jesus, with the ecstatic joy of young people who have found something truly new and exciting, literally dancing among the bones of the Roman Empire. It’s a metaphor of breathtaking power, one that (naturally) no other production of JCS in any form has ever been able to attempt, let alone duplicate. It gives Jewison’s movie a level of meaning that JCS has never had before or since, one that complements and enhances Webber and Rice’s original text. (These dances, by the way, were performed in desert heat that rose as high as 115 degrees or more. The performers could dance for no more than 30 seconds before Jewison had to call cut and let everybody step to the sidelines to towel off and rehydrate. That the dances — this one is the Simon the Zealot number — play on screen as sustained, high-energy performances is a testament to all concerned: Jewison, choreographer Rob Iscove, editor Antony Gibbs, and most of all, the dancers themselves.)

In his 2004 commentary on the DVD, Jewison credits production designer Richard Macdonald with the decision to shoot the picture on existing locations, making only minor modifications in the form of set dressing. Most of these locations — Avdat, King Herod’s Palace, the amphitheater at Beit She’an near Nazareth, where Jesus (Ted Neeley) is tried and condemned by Pontius Pilate (Barry Dennen) — were the ruined remains of Ancient Rome’s occupation of Palestine under the Caesars. Choosing to shoot in these places was a transformative decision, for it meant that Jesus Christ Superstar would show the early followers of Jesus, with the ecstatic joy of young people who have found something truly new and exciting, literally dancing among the bones of the Roman Empire. It’s a metaphor of breathtaking power, one that (naturally) no other production of JCS in any form has ever been able to attempt, let alone duplicate. It gives Jewison’s movie a level of meaning that JCS has never had before or since, one that complements and enhances Webber and Rice’s original text. (These dances, by the way, were performed in desert heat that rose as high as 115 degrees or more. The performers could dance for no more than 30 seconds before Jewison had to call cut and let everybody step to the sidelines to towel off and rehydrate. That the dances — this one is the Simon the Zealot number — play on screen as sustained, high-energy performances is a testament to all concerned: Jewison, choreographer Rob Iscove, editor Antony Gibbs, and most of all, the dancers themselves.)

Because Jesus Christ Superstar is a rock opera — or a “sung-through musical”, if you prefer — with no spoken dialogue, music is a constant on the soundtrack. Jewison makes it a constant in the image as well, fitting every camera movement, every cut, every dissolve, every zoom in or out to the rhythm of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s music. Both the performers and the camera are choreographed, using techniques he learned in early television, when he directed music-variety series like Your Hit Parade and the Andy Williams and Judy Garland shows. In Superstar he does things unavailable in live TV, too — slow motion, freeze-frames, etc. Always, everything to the music: a group of dancers will leap up and freeze midair, then we cut to another group similarly suspended, who come to life and complete the movement the first group began. Everything right on the driving beat; even something as simple as blowing out a candle matches the rhythm of the music.

All these techniques — moving and cutting to the music, playing with time and space — anticipated the music videos that would come along in the 1980s. As Ted Neeley put it in the DVD commentary, “This was the very first long-form music video ever done. MTV came as a result of this; after seeing these, MTV happened.”

That’s a bit of an exaggeration, granted, but

only a bit of one. The picture

is a long-form video, with a visual freedom that spans decades of movie-musical syntax, past and (from 1973) future. Jewison’s vision ranges both forward to MTV and back to variety TV, even to the unfettered imagination of Busby Berkeley: this is supposedly an impromptu performance by a band of players piling out of a bus, but the movie draws us on until we’re seeing things this troupe could never have stuffed into those wicker baskets, and we move freely around, among and over the performers in a way no audience could ever do. Take, for example, this exultant rendition of the title song, where the shade of Judas Iscariot (Carl Anderson, center) addresses Jesus with his own doubts and questions. This frame comes at the beginning of a soaring crane shot, the camera rising to heaven as the ensemble sings

“Jesus Christ / Jesus Christ / Who are you? What have you sacrificed?” The dancers glitter like silver angels, while

Anderson’s costume recalls that of Sly Stone in his performance at Woodstock — a reference that was inescapable to audiences in 1973, every one of whom had certainly seen the hit 1970 documentary.

All this, in the hands of Jewison, designer Macdonald, editor Gibbs, and cinematographer Douglas Slocombe, adds up to much more than gimmickry and camera tricks for their own sake. Everything is done in service to two things: (1) Andrew Lloyd Webber’s music; and (2) the complex human story at the heart of Tim Rice’s libretto — the very thing that (by all accounts I heard and read at the time) was swamped on Broadway under the campy glitz of Tom O’Horgan’s elephantine production. Even those tanks and fighter jets, which had me snorting in derision when I saw them in the trailer, were organic to the movie and made their symbolic points: the tanks were the irresistible, overpowering force driving Judas to his act of betrayal; the jets, the winged furies of conscience plaguing him for what he had done.

In discarding Tim Rice’s Ben-Hur-style treatment and swapping the cast of thousands for a cast of dozens, Bragg and Jewison could sharpen the focus on the libretto’s four central characters. First, of course, was Jesus (Ted Neeley), a man overwhelmed by a sense of having been assigned a divine mission without fully understanding what is expected of him. Jesus’s finest moment, and Neeley’s, comes in the soliloquy/aria “Gethsemane (I Only Want to Say)”, in which he sings Rice’s version of Matthew 26:39 (“O my Father, if it be possible, let this cup pass from me…”): “Take this cup away from me / For I don’t want to taste its poison / Feel it burn me, I have changed I’m not as sure / As when we started…”

Then Judas Iscariot (Carl Anderson), the character who drew Rice and Webber to write Jesus Christ Superstar in the first place, in an attempt to understand and explicate his motives. Jesus may be the title role, but in a very real sense Judas is the lead. After the overture — which in the movie serves to introduce the cast, the characters, and the setting — Judas opens the proceedings with the first song, “Heaven on Their Minds”. If Jesus is uncertain what God expects of him, Judas feels no such uncertainty; he believes he knows what Jesus’s mission is, and he very much fears Jesus has betrayed it, letting dangerous celebrity go to his head: “…And all the good you’ve done / Will soon get swept away / You’ve begun to matter more / Than the things you say…” At the opera’s climax, after his remorseful suicide, Judas returns, dropping from the sky dressed in white (a forgiven angel?) to ask what it was all about: “Don’t you get me wrong… / Only want to know…” As the movie’s Judas, Carl Anderson gave the performance of his life — a life, alas, that proved all too short; he died of leukemia in 2004, age 58.

Mary Magdalene was played by Yvonne Elliman, one of two members of the cast who played the same role in the original concept album, on Broadway for Tom O’Horgan, and for Norman Jewison on film. (Neeley was in the Broadway ensemble, understudied Jesus, and had played the role in concert.) Elliman’s Mary is devoted to Jesus without fully understanding why, paralleling Jesus’s own devotion to God. She expresses her love and confusion in the musical’s best-known and most enduring song, “I Don’t Know How to Love Him”, which became an enormous hit and was recorded by dozens of artists — most prominently, Helen Reddy, whose version was released almost simultaneously with the concept album’s appearance in the U.S. If Reddy stole Elliman’s thunder with her hit single, Elliman took it back again — and kept it for good — in the movie. Her heart-wrenching rendition is first among equals in the movie’s many high points, lovingly staged by Jewison and beautifully photographed in the dead of night by Douglas Slocombe.

The other cast member to go the distance from concept album to Broadway to Norman Jewison’s film was Barry Dennen as Pontius Pilate. (Dennen had, in fact, been responsible for Norman Jewison’s interest in

Superstar in the first place. He had just been cast as Pilate when he left for Yugoslavia, where he was to play a small role in Jewison’s movie of

Fiddler on the Roof; he took some

Superstar demo tapes with him to study, and he asked for Jewison’s advice on playing Pilate. One listen to Dennen’s samples and Jewison contacted Universal back in the States to nail down the screen rights for him — this, mind you, long before the Broadway production, and before the album had even been recorded.) Dennen’s Pilate is a decent man and a conscientious judge, but he’s not immune to Roman arrogance, nor to the exasperated condescension to Rome’s subjects that comes with it.

Jesus Christ Superstar took in $10.8 million at the box office, turning a more-than-respectable profit on Universal’s $3.6 million investment (both amounts were far more money in 1973 than they sound like now). It has by now acquired the aura — if not of a great movie musical, as I consider it — at least of a classic. In 1973, however, it weathered a torrent of critical scorn such as few movies have had to withstand. I remember particularly Paul D. Zimmerman’s screed in Newsweek: “…one of the true fiascos of modern cinema…Lord, forgive them. They knew not what they were doing.” There was a fiasco on display here, but it wasn’t the movie, it was Zimmerman’s dunderheaded review. I might have written it myself, if I had never bothered to, you know, actually see the movie. To be fair, Zimmerman was only echoing the near-unanimous sentiments of his critical fraternity. It was as if critics all over, embarrassed at the hyperbolic praise heaped on the album two years earlier, when it was compared to Bach and Handel, had decided in some secret meeting to take it out on Jewison’s movie. (Time Magazine no doubt regretted that they had already used the snark-line “I Was a Teenage Jesus” on 1961’s King of Kings.) Even when a review was positive — and Hollis Alpert’s in the Saturday Review was the only one I ever found — it carried a snide, patronizing air of I-can’t-believe-I’m-expected-to-take-this-thing-seriously. The critical reception was so savage that I sent a telegram to my uncle in Muncie, Indiana:

DISREGARD REPEAT DISREGARD ALL REVIEWS DON’T MISS JESUS CHRIST SUPERSTAR

* * *

All these musings on Jesus Christ Superstar are prompted by an experience I had last Sunday, August 25. Ted Neeley came to Sacramento on the third stop (after Los Angeles and San Francisco) in a cross-country tour commemorating the picture’s 40th anniversary. He brought with him a pristine archival print from the Universal vault, and the audience that day heard Superstar‘s soundtrack as it was meant to be heard for the first time in years, maybe decades. (The audio mix on all the video transfers — laserdisc, DVD and Blu-ray — is incorrect, the vocals too “hot” and instrumentals too “cold”.) Mr. Neeley — actually, I feel comfortable calling him Ted — met with audience members in the lobby before the screening, addressed us from the stage and fielded questions as the show was about to begin, and held genial court once again in the lobby afterwards. He chatted warmly with my friend Don (that’s Don on the left) and me for a good ten or 15 minutes, especially when he learned we were both actors, and that Don himself had played Pontius Pilate in a local production of the show. Like the movie itself, Ted Neeley has aged gracefully and could easily pass for 20 years younger than he is. Our visit with him was friendly and comfortable, a perfect way to top off the day’s reunion with one of my favorite movies.

As we were introduced, my first words to him were: “I have to thank you. I spent the entire summer of 1973 watching this movie in one of our local theaters here; I saw it 16 times in two months. I developed a huge crush on one of the dancers, but I never knew who she was until you identified her in your commentary on the DVD; it was Vera Biloshisky.” “Ahhh yes,” he said in that mellow Texas drawl that disappears only when he sings, “dear Vera. I just saw her yesterday. You weren’t alone in that; every guy on the set had a crush on Vera.” This is Vera dancing in the Simon the Zealot number (she’s visible, too, on the left in the midair shot of the female dancers a few pictures up); if you’ve seen Jesus Christ Superstar more than once I’ll wager you’ve noticed her yourself; she has an energy and vivacity that make her stand out even in that energetic, vivacious ensemble. (Ted Neeley’s own crush, by the way, went in a different direction. Just visible in the background between Vera’s outstretched limbs is Leeyan Granger. She and Ted met on the set; after shooting was finished they began dating, and she became — and remains — his wife.)

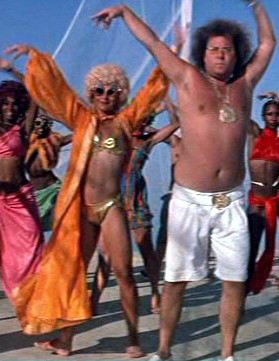

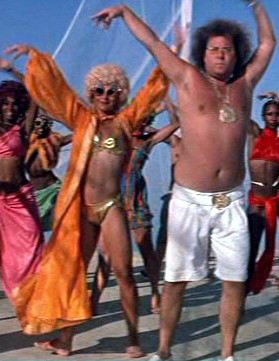

Here’s Vera again, cavorting with Josh Mostel’s King Herod on the shores of the Dead Sea. She’s unrecognizable behind those shades and under that platinum-blonde fright wig — at least I never recognized her, as much as I’ve seen the movie, until Ted pointed her out in a photo on my copy of the soundtrack LP. Vera Biloshisky, here’s a belated thank-you. You’ll never know, unless you’re reading this now, how you brightened my July and August of 1973. It was (for reasons I won’t go into here) an awkward time for me, and being able to watch you dancing in Jesus Christ Superstar helped get me through it.

Jesus Christ Superstar ends with yet another metaphor of breathtaking power, only this time it was entirely unplanned and unexpected. After the Crucifixion, after Jesus has given up the Ghost, the scene dissolves to the band of performers climbing back into the bus at dusk for the trip back to town. We see them mount the steps one by one — Barry Dennen, Josh Mostel, Larry Marshall (who plays Simon the Zealot), Bob Bingham and Kurt Yaghjian (the priests Caiaphas and Annas), dancers Jeff Hyslop and Robert LuPone, Yvonne Elliman, and finally Carl Anderson. Everyone except Ted Neeley. Anderson stands on the bus’s steps gazing at something in the distance behind us as the bus lurches away and lumbers down the hill back to the road. The picture dissolves again to what you see here: an empty cross silhouetted against a blood-red sunset.

At this precise moment, something happened that nobody planned or even noticed. “We were shooting through a telephoto lens,” Ted Neeley remembered, “from a couple of miles away, looking into the setting sun. We didn’t even see it until later, when we were watching the dailies.” From out of nowhere, a figure appeared — it’s barely visible here at the bottom of the image, about one-quarter in from the left. On screen, the figure moves like a ghostly apparition from left to right across the dark part of the screen under the cross. It’s a shepherd leading his flock; we can just make out their woolly fleeces bobbing along at the bottom of the frame. A shepherd, leading his flock past an empty cross. And nobody knew who he was or how he got there. “Somebody Else,” says Ted Neeley, “was directing that day.”

In his 2004 commentary on the DVD, Jewison credits production designer Richard Macdonald with the decision to shoot the picture on existing locations, making only minor modifications in the form of set dressing. Most of these locations — Avdat, King Herod’s Palace, the amphitheater at Beit She’an near Nazareth, where Jesus (Ted Neeley) is tried and condemned by Pontius Pilate (Barry Dennen) — were the ruined remains of Ancient Rome’s occupation of Palestine under the Caesars. Choosing to shoot in these places was a transformative decision, for it meant that Jesus Christ Superstar would show the early followers of Jesus, with the ecstatic joy of young people who have found something truly new and exciting, literally dancing among the bones of the Roman Empire. It’s a metaphor of breathtaking power, one that (naturally) no other production of JCS in any form has ever been able to attempt, let alone duplicate. It gives Jewison’s movie a level of meaning that JCS has never had before or since, one that complements and enhances Webber and Rice’s original text. (These dances, by the way, were performed in desert heat that rose as high as 115 degrees or more. The performers could dance for no more than 30 seconds before Jewison had to call cut and let everybody step to the sidelines to towel off and rehydrate. That the dances — this one is the Simon the Zealot number — play on screen as sustained, high-energy performances is a testament to all concerned: Jewison, choreographer Rob Iscove, editor Antony Gibbs, and most of all, the dancers themselves.)

In his 2004 commentary on the DVD, Jewison credits production designer Richard Macdonald with the decision to shoot the picture on existing locations, making only minor modifications in the form of set dressing. Most of these locations — Avdat, King Herod’s Palace, the amphitheater at Beit She’an near Nazareth, where Jesus (Ted Neeley) is tried and condemned by Pontius Pilate (Barry Dennen) — were the ruined remains of Ancient Rome’s occupation of Palestine under the Caesars. Choosing to shoot in these places was a transformative decision, for it meant that Jesus Christ Superstar would show the early followers of Jesus, with the ecstatic joy of young people who have found something truly new and exciting, literally dancing among the bones of the Roman Empire. It’s a metaphor of breathtaking power, one that (naturally) no other production of JCS in any form has ever been able to attempt, let alone duplicate. It gives Jewison’s movie a level of meaning that JCS has never had before or since, one that complements and enhances Webber and Rice’s original text. (These dances, by the way, were performed in desert heat that rose as high as 115 degrees or more. The performers could dance for no more than 30 seconds before Jewison had to call cut and let everybody step to the sidelines to towel off and rehydrate. That the dances — this one is the Simon the Zealot number — play on screen as sustained, high-energy performances is a testament to all concerned: Jewison, choreographer Rob Iscove, editor Antony Gibbs, and most of all, the dancers themselves.) That’s a bit of an exaggeration, granted, but only a bit of one. The picture is a long-form video, with a visual freedom that spans decades of movie-musical syntax, past and (from 1973) future. Jewison’s vision ranges both forward to MTV and back to variety TV, even to the unfettered imagination of Busby Berkeley: this is supposedly an impromptu performance by a band of players piling out of a bus, but the movie draws us on until we’re seeing things this troupe could never have stuffed into those wicker baskets, and we move freely around, among and over the performers in a way no audience could ever do. Take, for example, this exultant rendition of the title song, where the shade of Judas Iscariot (Carl Anderson, center) addresses Jesus with his own doubts and questions. This frame comes at the beginning of a soaring crane shot, the camera rising to heaven as the ensemble sings “Jesus Christ / Jesus Christ / Who are you? What have you sacrificed?” The dancers glitter like silver angels, while Anderson’s costume recalls that of Sly Stone in his performance at Woodstock — a reference that was inescapable to audiences in 1973, every one of whom had certainly seen the hit 1970 documentary.

That’s a bit of an exaggeration, granted, but only a bit of one. The picture is a long-form video, with a visual freedom that spans decades of movie-musical syntax, past and (from 1973) future. Jewison’s vision ranges both forward to MTV and back to variety TV, even to the unfettered imagination of Busby Berkeley: this is supposedly an impromptu performance by a band of players piling out of a bus, but the movie draws us on until we’re seeing things this troupe could never have stuffed into those wicker baskets, and we move freely around, among and over the performers in a way no audience could ever do. Take, for example, this exultant rendition of the title song, where the shade of Judas Iscariot (Carl Anderson, center) addresses Jesus with his own doubts and questions. This frame comes at the beginning of a soaring crane shot, the camera rising to heaven as the ensemble sings “Jesus Christ / Jesus Christ / Who are you? What have you sacrificed?” The dancers glitter like silver angels, while Anderson’s costume recalls that of Sly Stone in his performance at Woodstock — a reference that was inescapable to audiences in 1973, every one of whom had certainly seen the hit 1970 documentary.

The other cast member to go the distance from concept album to Broadway to Norman Jewison’s film was Barry Dennen as Pontius Pilate. (Dennen had, in fact, been responsible for Norman Jewison’s interest in Superstar in the first place. He had just been cast as Pilate when he left for Yugoslavia, where he was to play a small role in Jewison’s movie of Fiddler on the Roof; he took some Superstar demo tapes with him to study, and he asked for Jewison’s advice on playing Pilate. One listen to Dennen’s samples and Jewison contacted Universal back in the States to nail down the screen rights for him — this, mind you, long before the Broadway production, and before the album had even been recorded.) Dennen’s Pilate is a decent man and a conscientious judge, but he’s not immune to Roman arrogance, nor to the exasperated condescension to Rome’s subjects that comes with it.

The other cast member to go the distance from concept album to Broadway to Norman Jewison’s film was Barry Dennen as Pontius Pilate. (Dennen had, in fact, been responsible for Norman Jewison’s interest in Superstar in the first place. He had just been cast as Pilate when he left for Yugoslavia, where he was to play a small role in Jewison’s movie of Fiddler on the Roof; he took some Superstar demo tapes with him to study, and he asked for Jewison’s advice on playing Pilate. One listen to Dennen’s samples and Jewison contacted Universal back in the States to nail down the screen rights for him — this, mind you, long before the Broadway production, and before the album had even been recorded.) Dennen’s Pilate is a decent man and a conscientious judge, but he’s not immune to Roman arrogance, nor to the exasperated condescension to Rome’s subjects that comes with it.

At this precise moment, something happened that nobody planned or even noticed. “We were shooting through a telephoto lens,” Ted Neeley remembered, “from a couple of miles away, looking into the setting sun. We didn’t even see it until later, when we were watching the dailies.” From out of nowhere, a figure appeared — it’s barely visible here at the bottom of the image, about one-quarter in from the left. On screen, the figure moves like a ghostly apparition from left to right across the dark part of the screen under the cross. It’s a shepherd leading his flock; we can just make out their woolly fleeces bobbing along at the bottom of the frame. A shepherd, leading his flock past an empty cross. And nobody knew who he was or how he got there. “Somebody Else,” says Ted Neeley, “was directing that day.”

At this precise moment, something happened that nobody planned or even noticed. “We were shooting through a telephoto lens,” Ted Neeley remembered, “from a couple of miles away, looking into the setting sun. We didn’t even see it until later, when we were watching the dailies.” From out of nowhere, a figure appeared — it’s barely visible here at the bottom of the image, about one-quarter in from the left. On screen, the figure moves like a ghostly apparition from left to right across the dark part of the screen under the cross. It’s a shepherd leading his flock; we can just make out their woolly fleeces bobbing along at the bottom of the frame. A shepherd, leading his flock past an empty cross. And nobody knew who he was or how he got there. “Somebody Else,” says Ted Neeley, “was directing that day.”