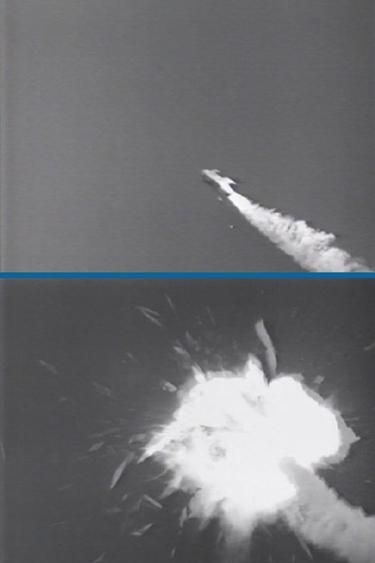

Day 3 of The Picture Show began with Chapters 8-11 of The Purple Monster Strikes. Things are getting a little repetitive — sometimes literally, as the two directors (Spencer Bennett, Fred C. Brannon) and six writers (do you really care?) begin stretching things by recapping earlier plot points and cliffhanger thrills. Thus does Republic turn 12 chapters into 15. Bob Bloom’s program notes, quoting movie-serial blogger Jerry Blake, tell us that (1) Purple Monster boasts a plethora of fine cliffhangers, many of them supplied by those ingeniously resourceful special-effects artists, brothers Howard and Theodore Lydecker; and (2) this was one of the last Republic serials to make extensive use of the brothers’ original effects; henceforth, for the ten years or so left to Republic serials, the studio would rely more on stock footage of their earlier work.

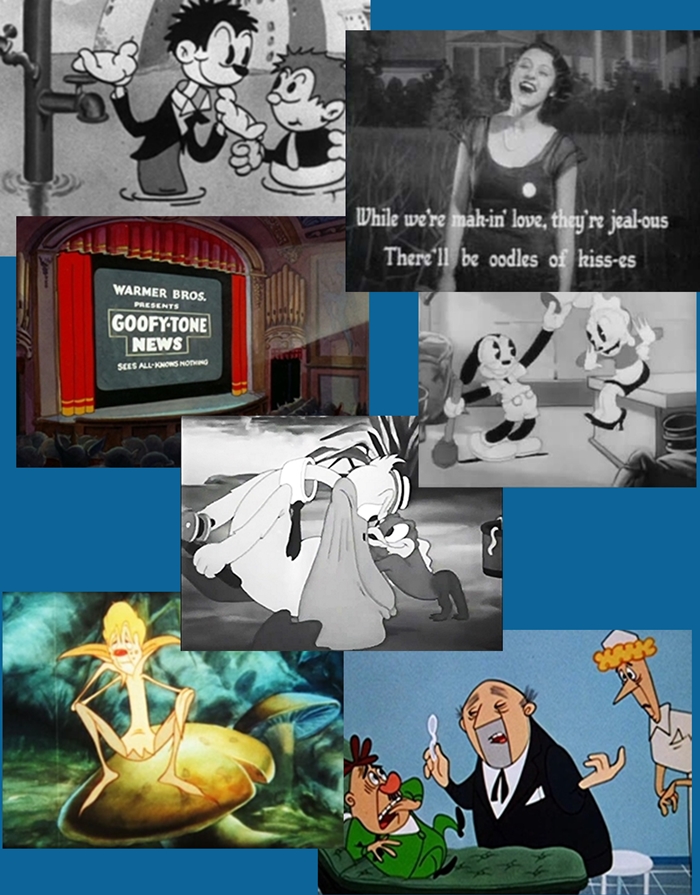

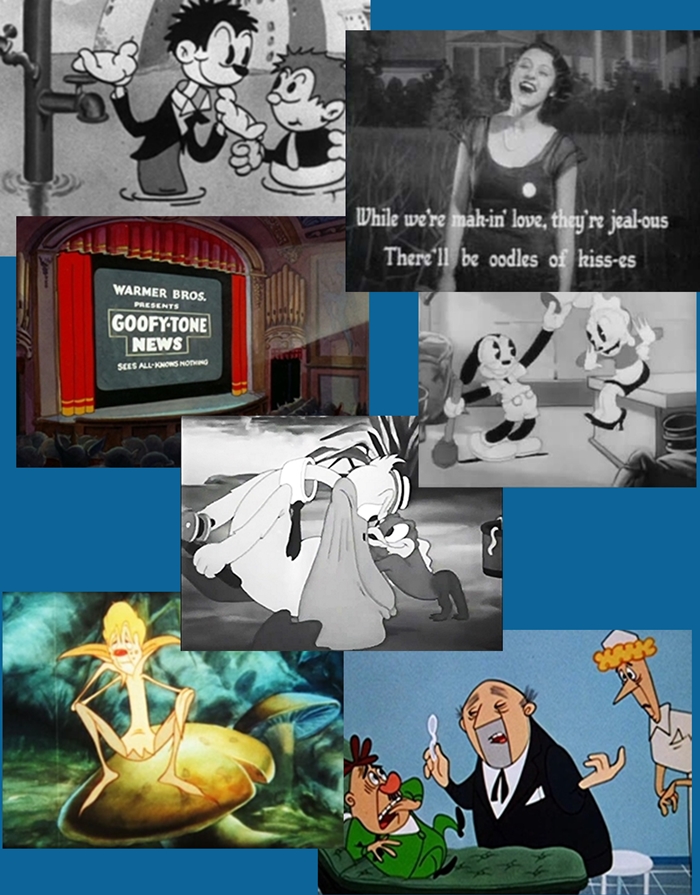

Then it was time for The Picture Show’s annual Saturday morning animation program, curated and annotated by the worthy Stewart McKissick. And here I’m forced to make a confession that I’ve been dreading. It seems that at last year’s animation program, the schedule included Frank Tashlin’s The Tangled Angler (Columbia, 1941), and the program book reflected that. However, the supplier sent the wrong print: Tangled Travels (also Columbia, 1944) arrived instead of The Tangled Angler. The substitution came too late to change the book, and the book was what I relied on in my post. (Those cartoons do tend to blur together if you’re not careful.) In writing my post last year, I refreshed my memory (which, as it happened, was faulty) with The Tangled Angler on YouTube. Fortunately, Tangled Travels is also on YouTube, so I’ve been able to update my post from last year (I had hoped to make the change quietly with nobody the wiser, but I included an image from Angler in my cartoon collage — there it is again below, third row center — and it couldn’t be removed). Anyhow, The Tangled Angler made its belated appearance this year, and I’ve transferred my remarks from last year’s post to this one.

As for this year’s cartoons (with links to YouTube where available):

Joint Wipers (1932) (top row, left) was an example of the other Tom and Jerry, the ones — humans, not cat and mouse — produced by Van Beuren Studios between 1931 and ’33. In this one the boys are plumbers, summoned to fix some leaky pipes and only making matters worse, with an amusing song-and-dance interlude in the midst of all the water damage. The YouTube link above has a rather blurry image; the image is better at this link, albeit with a rambling commentary by one Justin Leal.

Also from 1932, Hollywood Diet was a Terrytoon about “Dr. Fathead’s House of Painless Fat Removing” — in later terms, a weight-loss clinic. The fat jokes came thick and heavy (if you’ll pardon the expression), with clients — mainly lazy, spoiled and obese Hollywood housewives — carted around on hand-trucks by sweating attendants and shoveled into moving vans for transport. Fat-shaming was alive and well in 1932, and this one is not for the sensitive. So be warned before you hop over to YouTube.

With Down Among the Sugar Cane (top row, right) we continued to linger in 1932, for a bouncing-ball singalong from Max and Dave Fleischer. After their customary surrealistic imagery, the singing was led by winsome Lillian Roth (whose troubles with alcohol, documented in the book and movie I’ll Cry Tomorrow, were not yet generally known). Like last year’s You Try Somebody Else, the song was an unfamiliar one, but the Picture Show audience gamely warbled along. (The Fleischers were always good about planting the tune firmly in the audience’s head before asking anyone to sing.)

We left 1932 behind with Ham and Eggs (1933) (second row, right), one of Walter Lantz’s Oswald the Lucky Rabbit cartoons for Universal. Oswald’s back story is more interesting that any of his cartoons. He had been poached from Walt Disney in 1927, forcing Disney to come up with some other tent-pole character (the result was Mickey Mouse, and no one ever wrestled a character away from Walt Disney again). Meanwhile, at Universal, Charles Mintz and George Winkler tried to make something of Oswald; eventually the character fell into Lantz’s hands. It wasn’t until the introduction of Andy Panda and Woody Woodpecker that Walter Lantz struck cartoon gold; until then, Lantz, like Mintz and Winkler before him, was unable to make Oswald anything more that what he had been all along: a dry run for Mickey Mouse. Still, Lantz’s Oswald cartoons weren’t bad, and this one was enjoyable. In it, Oswald and his girl (who looks more like a dog than a rabbit to me) run a short-order diner, dealing with a succession of querulous customers with a smile and a song. Fred “Tex” Avery, early in his career, was among the animators.

The Masque Raid (1937) was a Krazy Kat cartoon produced by the busy Charles Mintz for Columbia. This was an example of a sub-genre of cartoon that appeared regularly in the 1930s: After hours in some commercial establishment (bookstore, food market, toy shop, newsstand, etc.), the products on the shelves come to life and cavort until the dawn’s early light. Here it was a costume shop, and Krazy is the night watchman observing the doings of various exotic garments as they spring off the racks, all while a rainstorm rages outside. Spoiler alert: Krazy has dozed off on the job, and it’s all a dream.

She Was an Acrobat’s Daughter (1937) (second row, left) was my favorite cartoon on the program — as, indeed, it’s been a favorite of mine ever since it cropped up on television in the 1950s. (Alas, Warner Bros. cartoons are thin on the ground at YouTube, and I’m unable to link to this one.) This was the first color cartoon of the day — but it was a bit of a tease, as it takes place in a movie theater and much of its running time is taken up (as in the illustration) with the black-and-white films on the screen. They were fun, though; the main feature was a spoof of The Petrified Forest (“The Petrified Florist“), featuring cameo appearances by animated caricatures of Bette Davis and Leslie Howard. No Bogart, however. Bogie’s stardom was still a few years off, and odds are that even the best caricature of him (there were a number of good ones to come in the ’40s) would have gone unrecognized by 1937 audiences, while everyone knew Bette and Leslie.

The Frog Pond (1938) was directed by Ub Iwerks for Columbia during his years away from Disney. The story wanders all over the place, but pleasantly. What begins with fairly straight anthropomorphic-frog antics around a lily pond segues into the story of a sort of frog gang-lord enlisting underlings to build him a castle on a particularly roomy lily pad, then throwing himself a party at a wetland nightclub, with elaborate Busby-Berkeley-style song and dance, and finally being sent (literally) down the river to land in Croak Croak Prison (“Croak Croak”/”Sing Sing”, get it?). It ends with the Frogfather smashing rocks to spell out “Crime Does Not Pay”.

Then, at last, we got the long-delayed screening of The Tangled Angler (1941), directed by Frank Tashlin for Columbia. Last year this was planned to be a sort of companion piece to Tashlin’s live-action comedy Marry Me Again (1953) with Robert Cummings and Marie Wilson, Tashlin being the only cartoon director to transition successfully to live-action while preserving his freewheeling cartoon style. Alas, there was no Tashlin picture to go with it this year, so Angler was forced to stand on its own — which it did very nicely, thank you. Made during his brief one-year sojourn at Columbia’s cartoon unit between stints at Warner Bros. (the Looney Tunes influence is clear), Angler tells of the battle between a fisherman pelican and the slippery (in every sense) fish he can’t manage to land.

Dance of the Weed (1941) (bottom row, left) was produced at MGM by Rudolf Ising (during a hiatus in his partnership with Hugh Harman). Heavily influenced by Fantasia the year before, and foreshadowing Bambi to come in ’42, it was a lush pastoral ballet with dancing flora of various botanical phyla and featuring a flirtatious pas de deux between a gallumphing yellow-brown weed and a delicate green-and-orange poppy. It was gorgeously colorful, with individual images suitable for framing. Interesting sidelight: One of the cartoon’s uncredited writers was Gus Arriola, who later in 1941 left MGM’s cartoon unit to create the comic strip Gordo for United Features Syndicate; he would write and draw the strip until 1985.

SH-H-H-H-H-H (1955) (bottom row, right) was the great Tex Avery’s swan song as a writer/director of theatrical cartoons. Fired by MGM in 1953, he landed back where he started with Walter Lantz at Universal (Universal International, by then). SH-H-H-H-H-H shows him with his wit and talent undimmed. The story: A nightclub musician, his nerves jangled by the constant cacophony of the band he plays with, goes off to a resort in the Swiss Alps (“The Hush-Hush Lodge”) for rest, relaxation, and regeneration — only to be jangled anew by the guests in the room next door. Be prepared for a twist ending.

Nick Santa Maria — not only Benny Biffle of Michael Schlesinger’s 1930s-style Biffle and Shooster shorts, but also a devoted authority on Abbott and Costello — introduced the duo’s Keep ‘Em Flying from their busy year of 1941 (January: Buck Privates; May: In the Navy; August: Hold That Ghost; then this one in November — not to mention Ride ‘Em Cowboy, released in January ’42 but filmed in ’41). This completed Bud and Lou’s trilogy of service comedies begun with Buck Privates and In the Navy; they wouldn’t return to the genre until Buck Privates Come Home in 1947, which actually veered off on a non-military tangent. In the meantime, they played Blackie (Bud) and Heathcliff (Lou), sidekicks to carnival stunt pilot Jinx Roberts (Dick Foran) who become part of his ground crew when he enlists in the U.S. Army Air Corps. (By mid-1941 it was generally accepted that we’d be in that war of Hitler’s sooner or later — though nobody expected Pearl Harbor, exactly.)

Nick Santa Maria — not only Benny Biffle of Michael Schlesinger’s 1930s-style Biffle and Shooster shorts, but also a devoted authority on Abbott and Costello — introduced the duo’s Keep ‘Em Flying from their busy year of 1941 (January: Buck Privates; May: In the Navy; August: Hold That Ghost; then this one in November — not to mention Ride ‘Em Cowboy, released in January ’42 but filmed in ’41). This completed Bud and Lou’s trilogy of service comedies begun with Buck Privates and In the Navy; they wouldn’t return to the genre until Buck Privates Come Home in 1947, which actually veered off on a non-military tangent. In the meantime, they played Blackie (Bud) and Heathcliff (Lou), sidekicks to carnival stunt pilot Jinx Roberts (Dick Foran) who become part of his ground crew when he enlists in the U.S. Army Air Corps. (By mid-1941 it was generally accepted that we’d be in that war of Hitler’s sooner or later — though nobody expected Pearl Harbor, exactly.)

Also in the cast was band singer Carol Bruce, whose movie career never really took off, but who was good enough to deserve better breaks. All through the screening I struggled to figure out why she looked so familiar, but it never came. It wasn’t until later, reading Dave Domagala’s program notes, that I got my answer: From 1978 to ’82 she had a recurring role on WKRP in Cincinnati as Lillian Carlson, the flinty station owner and mother of manager Arthur Carlson (Gordon Jump). I would never have figured that out on my own, but now that I know, I can see it. The eyes, I think, are a bit of a giveaway.

Also in the cast was band singer Carol Bruce, whose movie career never really took off, but who was good enough to deserve better breaks. All through the screening I struggled to figure out why she looked so familiar, but it never came. It wasn’t until later, reading Dave Domagala’s program notes, that I got my answer: From 1978 to ’82 she had a recurring role on WKRP in Cincinnati as Lillian Carlson, the flinty station owner and mother of manager Arthur Carlson (Gordon Jump). I would never have figured that out on my own, but now that I know, I can see it. The eyes, I think, are a bit of a giveaway.

Another female holding her own with Bud and Lou — not surprisingly — was Martha Raye, hilarious again as identical twins, one sweet, shy and demure, the other — well, more like Martha Raye. Her scenes, especially with Lou (one sister has a crush on him, the other doesn’t) and her rousing delivery of the hit song “Pig Foot Pete”, were highlights. Beyond that, Abbott and Costello are already falling into a bit of a routine formula — not surprising when you’re cranking pictures out as fast as this.

After the lunch break came Lights Out (1923). I’m sorry I didn’t see this one — took too long for lunch, then opted for the dealers’ room instead — because it sounds interesting. For one thing, it was presented in digital projection rather than the usual 16mm because it was believed lost until 2021, when a digital copy (labeled with the wrong title) was found to have been gifted to the Library of Congress by the Russian Gosfilmofond archive in 2010. The plot has to do with a couple of semi-reformed crooks who con a screenwriter into penning a movie recounting their last big heist — this as a ploy to lure their erstwhile confederate, who absconded to Brazil with all the loot, out of hiding. Joe Harvat’s program notes tell us Lights Out was a big hit, with “universally glowing” reviews — but the only review I found (Variety, Oct. 25, ’23) was a pretty merciless pan. Still, I’m sorry I missed it; I’d probably have to make an appointment with the Library of Congress to have another chance to see it. The story, based on a Broadway play that closed after two weeks in August 1922, was remade in 1938 as Crashing Hollywood with Lee Tracy.

I sure didn’t miss the next screening, and boy, am I glad, because this was another highlight of the whole weekend — for me at least, and I’m pretty sure I’m not alone (witness the fact that a poster for it graced the cover of The Picture Show’s program book). The picture, introduced by author and historian James D’Arc, was Blaze of Noon (1947), a movie whose continuing obscurity is a mystery that will confound me to the end of my days. I mean, for starters, just take a gander at the names on this lobby card: Anne Baxter, William Holden, Sonny Tufts, William Bendix, Sterling Hayden, Howard da Silva, director John Farrow. Then there are the names you can’t see here. The cinematographer: William C. Mellor (A Place in the Sun, The Diary of Anne Frank, Giant). The composer: Adolph Deutsch, one of Hollywood’s most underrated composers (he contributed hugely to John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon, among many others). The writers: Arthur Sheekman and Frank “Spig” Wead (the aviator-turned-screenwriter played by John Wayne in John Ford’s biopic The Wings of Eagles). Finally and especially, the author on whose book Wead and Sheekman’s script was based: Ernest K. Gann. Blaze of Noon was Gann’s second bestseller; his first, Island in the Sky, had made him a literary celebrity. His later books in the ’50s and ’60s (The High and the Mighty, Twilight for the Gods, Fate Is the Hunter) would make his name even bigger.

I sure didn’t miss the next screening, and boy, am I glad, because this was another highlight of the whole weekend — for me at least, and I’m pretty sure I’m not alone (witness the fact that a poster for it graced the cover of The Picture Show’s program book). The picture, introduced by author and historian James D’Arc, was Blaze of Noon (1947), a movie whose continuing obscurity is a mystery that will confound me to the end of my days. I mean, for starters, just take a gander at the names on this lobby card: Anne Baxter, William Holden, Sonny Tufts, William Bendix, Sterling Hayden, Howard da Silva, director John Farrow. Then there are the names you can’t see here. The cinematographer: William C. Mellor (A Place in the Sun, The Diary of Anne Frank, Giant). The composer: Adolph Deutsch, one of Hollywood’s most underrated composers (he contributed hugely to John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon, among many others). The writers: Arthur Sheekman and Frank “Spig” Wead (the aviator-turned-screenwriter played by John Wayne in John Ford’s biopic The Wings of Eagles). Finally and especially, the author on whose book Wead and Sheekman’s script was based: Ernest K. Gann. Blaze of Noon was Gann’s second bestseller; his first, Island in the Sky, had made him a literary celebrity. His later books in the ’50s and ’60s (The High and the Mighty, Twilight for the Gods, Fate Is the Hunter) would make his name even bigger.

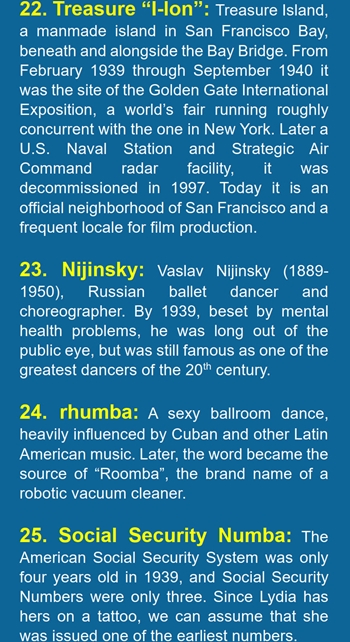

Taken all in all, that’s one hell of a pedigree.

The story had to do with the four McDonald brothers — Roland (Tufts), Colin (Holden), Tad (Hayden) and Keith (Johnny Sands) — stunt fliers with a traveling carnival in the 1920s who all hang together when Colin decides to quit show business for a job in the burgeoning airmail industry, represented by a gruff but compassionate Howard da Silva. Anne Baxter played a nurse who marries William Holden and becomes the unwitting object of unrequited love from brother Sterling Hayden, while William Bendix was another aviator who has trouble forsaking his hell-raising barnstorming antics and knuckling down to business. Spoiler alert: the life of pioneering airmail pilots comes at a cost to the four brothers, with more than their share of heartache.

Not to mince words, Blaze of Noon is a terrific picture, one that can stand with better-known movies about early flight like Wings, I Wanted Wings, Dive Bomber and Men with Wings without hanging its head. I’m an ardent partisan of John Farrow’s pictures Night Has a Thousand Eyes (’48) and Alias Nick Beal (’49), while most movie buffs are partial to his noir classic The Big Clock (’48), but this one is fully their equal — and as a piece of sheer directorial brio may be the best of the bunch. Note, for example (if you ever get the chance to see it), the opening shot of the story proper (after a prologue singing the praises of airmail pilots): Farrow stages a long, complex tracking shot weaving through the busy carnival with its dancing girls, barkers male and female, rides, popcorn and balloon vendors, and multitude of country patrons ogling the sights and munching their hot dogs and cotton candy. The camera discovers the four brothers leaning against a game booth chitchatting, then follows them back to where the shot started, coming to rest on William Holden flirting with dancer Jean Wallace (that’s her flashing her gams on the lobby card above). It’s a real tour-de-force take that runs a full minute-and-42-seconds, establishing both the four brothers and the world they work in without calling attention to its own virtuosity — one of the highlights of Farrow’s whole career, and that of cinematographer William Mellor. And Blaze of Noon has more to come. It’s a pity that this pre-1950 Paramount languishes in the Universal vaults without a home-video release to give it the reputation it deserves. Indeed, a collector friend of mine recently tried to find a buyer for a 16mm print without success — not even other collectors had ever heard of it. (Part of the problem may be the title; it’s Ernest Gann’s own, but it gives no hint of what the movie is about. It makes it sound like a western.) If this near-classic ever does come out on video, remember: You heard about it here first.

After the dinner break it was the final Laurel and Hardy short of the weekend: Wrong Again (1929), technically a “sound” film but not a talkie; rather, it was a silent with no spoken dialogue, but with a soundtrack of music and sound effects, giving Picture Show accompanists Philip Carli and David Drazin a break for a couple of reels. (Like other studio heads, Hal Roach used this semi-sound approach to transition his studio into the era of talking pictures). In Wrong Again, The Boys played stable attendants tending to a horse named Blue Boy. When the famous Gainsborough painting of the same name is stolen and the millionaire owner offers a $5,000 reward, Stan and Ollie think he’s willing to pay that much for the horse. Imagine the possibilities.

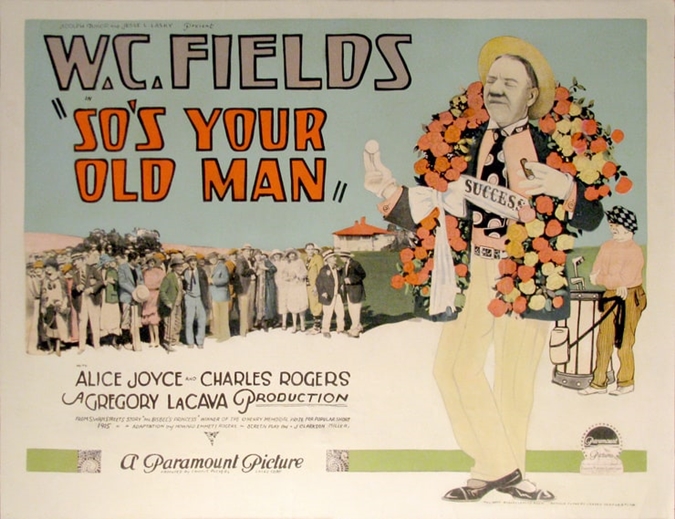

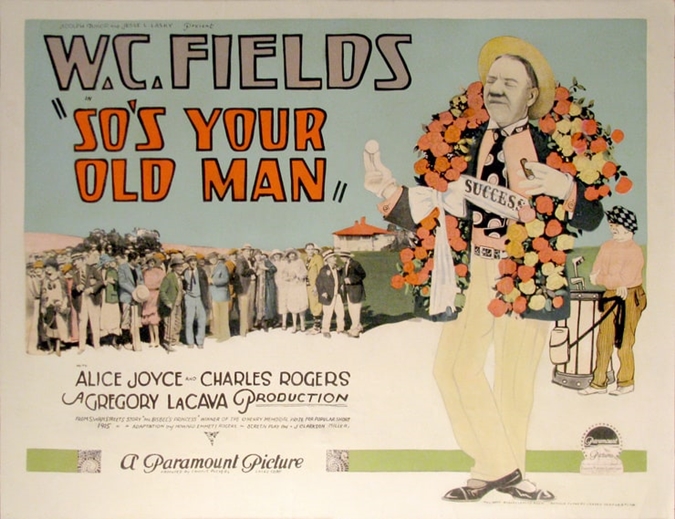

Either Philip Carli or David Drazin — sorry, I forget which — was pressed back into service for So’s Your Old Man (1926), one of W.C. Fields’s surviving silent pictures. Like two of his others, Sally of the Sawdust (1925) and It’s the Old Army Game (’26), it was later remade as a talkie. Sally of the Sawdust became Poppy (’36), It’s the Old Army Game returned (more or less) as It’s a Gift (’34), and So’s Your Old Man was remade as You’re Telling Me! (also ’34). In both So’s Your Old Man and You’re Telling Me!, Fields plays Sam Bisbee, an eccentric small-town inventor whose social-climbing wife is ashamed of him because of the way he and his family are looked down on by the town’s “better” people. Bisbee doesn’t care what the snobs think of him, but he wants to make good for the sake of his daughter (the delightfully named Kittens Reichert), who is in love with Kenneth Murchison (Charles “Buddy” Rogers), son of the town’s snootiest grande dame. Bisbee travels to an auto manufacturers’ convention to sell his invention, a shatterproof windshield, but when someone switches his test vehicle for a regular car, his demonstration fails and he becomes a laughingstock. Returning home in disgrace, he befriends a young woman on the train (Alice Joyce) who, unbeknownst to him, is a royal princess on a goodwill tour of America, and she determines to do what she can to help him.

Either Philip Carli or David Drazin — sorry, I forget which — was pressed back into service for So’s Your Old Man (1926), one of W.C. Fields’s surviving silent pictures. Like two of his others, Sally of the Sawdust (1925) and It’s the Old Army Game (’26), it was later remade as a talkie. Sally of the Sawdust became Poppy (’36), It’s the Old Army Game returned (more or less) as It’s a Gift (’34), and So’s Your Old Man was remade as You’re Telling Me! (also ’34). In both So’s Your Old Man and You’re Telling Me!, Fields plays Sam Bisbee, an eccentric small-town inventor whose social-climbing wife is ashamed of him because of the way he and his family are looked down on by the town’s “better” people. Bisbee doesn’t care what the snobs think of him, but he wants to make good for the sake of his daughter (the delightfully named Kittens Reichert), who is in love with Kenneth Murchison (Charles “Buddy” Rogers), son of the town’s snootiest grande dame. Bisbee travels to an auto manufacturers’ convention to sell his invention, a shatterproof windshield, but when someone switches his test vehicle for a regular car, his demonstration fails and he becomes a laughingstock. Returning home in disgrace, he befriends a young woman on the train (Alice Joyce) who, unbeknownst to him, is a royal princess on a goodwill tour of America, and she determines to do what she can to help him.

Fields’s silents suffer today because, unlike audiences of the 1920s, we know well his inimitable, oft-imitated voice and how much it contributed to his comedy, and we miss it in a way that viewers back then couldn’t. Still, So’s Your Old Man holds up nicely because You’re Telling Me! was later a virtual shot-for-shot remake (director Erle C. Kenton was smart enough to imitate original director Gregory La Cava slavishly) and it’s easy to hear Fields’s voice in our heads as we read the intertitles. (Practically the only difference is that in You’re Telling Me! Sam Bisbee’s invention is a puncture-proof tire rather than shatterproof glass.)

Eric Grayson’s program notes tell a fascinating, convoluted story about why So’s Your Old Man is out of circulation. Let’s see if I can make it simple. Paramount sold their 1930-50 library to Universal; that’s why things like the Marx Brothers’ pre-MGM titles, Fields’s talkies, and the Bob Hope/Bing Crosby Road pictures sport the Universal Globe before the Paramount Mountain takes the screen. Paramount still theoretically owns their 1923-29 silents, but except for special cases like Wings, they don’t particularly care. On top of that, So’s Your Old Man is based on a short story by Julian Street (1879-1947), and even though both picture and story are in the public domain, Paramount is contractually obligated to compensate the Street estate for any screenings or releases of the picture. Back in the ’70s, when Street’s survivors were easier to track down, Paramount made a deal to distribute You’re Telling Me!, but So’s Your Old Man was a silent, so — I say again — they didn’t care. Nowadays, there’s more of a market for silent cinema, but who and where Street’s surviving relatives are is anybody’s guess. Fortunately, some enterprising bootlegger copied Fields’s Paramount silents, including So’s Your Old Man, for the collectors’ market on their way to whatever vault or archive they were earmarked for. How one of those prints found itself in Columbus for The Picture Show is (again) anybody’s guess.

I suspect I’ve rather garbled the story in trying to simplify it — but I’ve spent enough time on it, I think. If you can get in touch with Eric Grayson, maybe he can explain it to you better than I have.

The Turning Point (1952) was a tight, economical crime thriller from Paramount, writers Warren Duff and Horace McCoy, and director William Dieterle, whose pictures — The Life of Emile Zola, A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1935), The Story of Louis Pasteur, The Hunchback of Notre Dame (’39) — were usually less gritty and street-wise. Edmund O’Brien played John Conroy, a crusading special prosecutor charged with breaking up a crime syndicate in a large, Midwestern Chicago-type city masterminded by “trucking executive” Neil Eichelberger (Ed Begley). As his chief investigator he appoints his father, veteran straight-arrow cop Matt Conroy (Tom Tully). Jerry McKibbon (William Holden), an equally crusading newspaper reporter and John Conroy’s lifelong friend, keeps a close eye on the investigation; he’s sympathetic, but he fears Conroy is too inexperienced to take on the criminal conspiracy he’s trying to tackle. McKibbon uncovers the fact that Conroy’s father Matt is in fact a “mole” on Eichelberger’s payroll — and, making things even more uncomfortable, McKibbon is falling in love with Conroy’s assistant and paramour Amanda Waycross (Alexis Smith). The picture was really strong stuff, with some shocking violence — especially for 1952 — plus several very unsettling turns of the plot before the final fade-out.

The Turning Point (1952) was a tight, economical crime thriller from Paramount, writers Warren Duff and Horace McCoy, and director William Dieterle, whose pictures — The Life of Emile Zola, A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1935), The Story of Louis Pasteur, The Hunchback of Notre Dame (’39) — were usually less gritty and street-wise. Edmund O’Brien played John Conroy, a crusading special prosecutor charged with breaking up a crime syndicate in a large, Midwestern Chicago-type city masterminded by “trucking executive” Neil Eichelberger (Ed Begley). As his chief investigator he appoints his father, veteran straight-arrow cop Matt Conroy (Tom Tully). Jerry McKibbon (William Holden), an equally crusading newspaper reporter and John Conroy’s lifelong friend, keeps a close eye on the investigation; he’s sympathetic, but he fears Conroy is too inexperienced to take on the criminal conspiracy he’s trying to tackle. McKibbon uncovers the fact that Conroy’s father Matt is in fact a “mole” on Eichelberger’s payroll — and, making things even more uncomfortable, McKibbon is falling in love with Conroy’s assistant and paramour Amanda Waycross (Alexis Smith). The picture was really strong stuff, with some shocking violence — especially for 1952 — plus several very unsettling turns of the plot before the final fade-out.

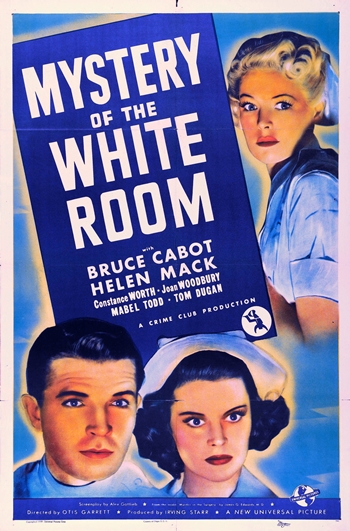

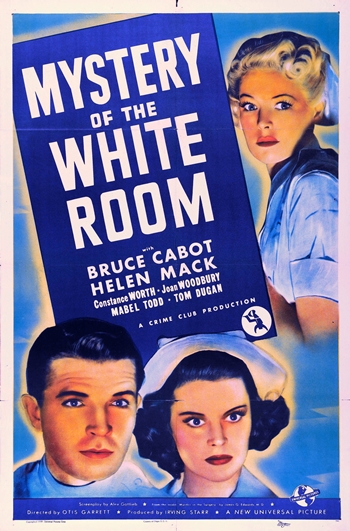

Day 3 wrapped up with Mystery of the White Room (1939), an installment of the short-lived Crime Club series from Universal. (Short-lived in duration, that is; producer Irving Starr managed to knock out 11 B-mysteries during the two years the franchise lasted. The inspiration for the series, the Crime Club imprint of Doubleday Publishers, had a more prosperous run: It lasted from 1928 to 1991 and published nearly 2,500 titles. There was a short-lived radio series too.)

Day 3 wrapped up with Mystery of the White Room (1939), an installment of the short-lived Crime Club series from Universal. (Short-lived in duration, that is; producer Irving Starr managed to knock out 11 B-mysteries during the two years the franchise lasted. The inspiration for the series, the Crime Club imprint of Doubleday Publishers, had a more prosperous run: It lasted from 1928 to 1991 and published nearly 2,500 titles. There was a short-lived radio series too.)

The “White Room” of the title was literally that — the operating room at a big-city hospital. During a tense operation the lights go out, and during the brief darkness the hospital’s head surgeon (Addison Richards) is murdered with a scalpel to the heart. Complicating the investigation is the fact that both assisting doctors (Bruce Cabot, Roland Drew) and both nurses (Helen Mack, Constance Worth) — everybody in the room, it seems, except for the patient — had reason to bear a grudge. Not only that, but they were all wearing rubber gloves, so there are no fingerprints to enter into evidence. Bruce Cabot and Helen Mack were top-billed as doctor-and-nurse sweethearts, so the rules of 1930s B-movies suggested they’d be innocent in the end — but they came in for their share of suspicion nevertheless. It was a clever little locked-room murder mystery that sets up and resolves its mystery in a no-frills 57 minutes — although some tiresome comic relief from orderly Tom Dugan and switchboard operator Mabel Todd (whose rasping, nasal, annoying voice makes Fran Drescher sound like Angela Lansbury) makes the picture feel several minutes longer.

And that was it for Saturday’s program. Three down and one to go.

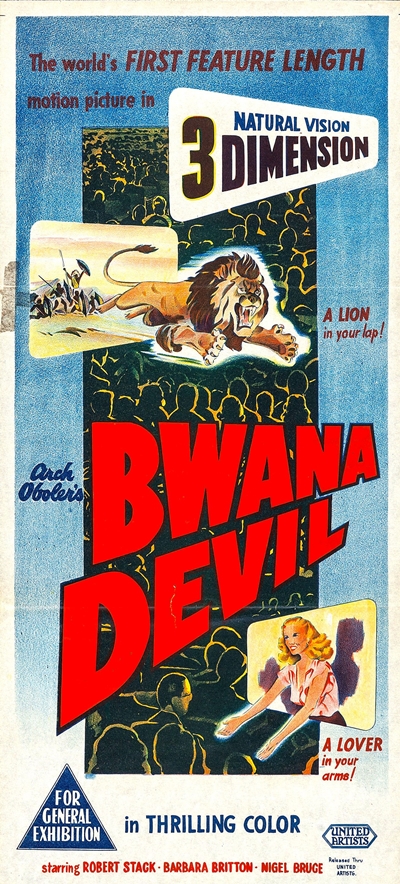

As has become traditional, the long weekend kicked off on the evening of Wednesday, May 22 with a screening, in conjunction with the Picture Show, at the Wexner Center for the Arts on the campus of Ohio State University. This year the main attraction was a digital restoration of Bwana Devil, the 1952 surprise hit that launched the original 3D craze. Produced, written and directed by the eccentric Arch Oboler, Bwana Devil was loosely based on the man-eaters of Tsavo, a pair of rogue lions who went on a killing spree in 1898, slaughtering enough native African and Indian workers on the Kenya-Uganda Railway to bring construction to a standstill for months (the story was filmed again, with slightly more fidelity to the facts, as The Ghost and the Darkness in 1996). Coming when it did, with Hollywood reeling from the onslaught of television and desperate to lure audiences back into theaters, Bwana Devil made 3D look like just what the faltering movie business needed.

As has become traditional, the long weekend kicked off on the evening of Wednesday, May 22 with a screening, in conjunction with the Picture Show, at the Wexner Center for the Arts on the campus of Ohio State University. This year the main attraction was a digital restoration of Bwana Devil, the 1952 surprise hit that launched the original 3D craze. Produced, written and directed by the eccentric Arch Oboler, Bwana Devil was loosely based on the man-eaters of Tsavo, a pair of rogue lions who went on a killing spree in 1898, slaughtering enough native African and Indian workers on the Kenya-Uganda Railway to bring construction to a standstill for months (the story was filmed again, with slightly more fidelity to the facts, as The Ghost and the Darkness in 1996). Coming when it did, with Hollywood reeling from the onslaught of television and desperate to lure audiences back into theaters, Bwana Devil made 3D look like just what the faltering movie business needed.

As we all decompress from the Holiday Season, I want to pause and pay tribute to a particular Christmas movie, one of the least known and one of the best. It distills the spirit of Christmas as well as — sometimes better than — more familiar titles, worthy as they are. Without being preachy or even overtly religious, it presents that spirit in the form of a parable — the form, in fact, favored by Jesus himself in the Gospels. And it’s only 22 minutes long.

As we all decompress from the Holiday Season, I want to pause and pay tribute to a particular Christmas movie, one of the least known and one of the best. It distills the spirit of Christmas as well as — sometimes better than — more familiar titles, worthy as they are. Without being preachy or even overtly religious, it presents that spirit in the form of a parable — the form, in fact, favored by Jesus himself in the Gospels. And it’s only 22 minutes long. It’s called Star in the Night, released by Warner Bros. on October 13, 1945. It opens on a cold night (Christmas Eve, as we later learn) somewhere in the desert of the American Southwest — Arizona, perhaps, or Nevada or New Mexico. Three cowboys are ambling along on horseback. Their arms and saddles are laden with toys, Yuletide decorations and other “doodads” which, in a spasm of holiday cheer, they have bought from a general store in the town they left back a ways, though they haven’t the slightest idea what to do with them or whom they might give them to.

It’s called Star in the Night, released by Warner Bros. on October 13, 1945. It opens on a cold night (Christmas Eve, as we later learn) somewhere in the desert of the American Southwest — Arizona, perhaps, or Nevada or New Mexico. Three cowboys are ambling along on horseback. Their arms and saddles are laden with toys, Yuletide decorations and other “doodads” which, in a spasm of holiday cheer, they have bought from a general store in the town they left back a ways, though they haven’t the slightest idea what to do with them or whom they might give them to.

The camera takes us there long before the cowboys have time to arrive. It turns out the star the cowboys see is no astronomical phenomenon; it’s an advertising sign, illuminated by 102 light bulbs. Recently purchased from a defunct movie theater (“Star Picture Palace”), it’s been newly installed over a roadside inn, the Star Auto Court. As a lone vagabond approaches from the road, the Star’s proprietor, Nick Catapoli (J. Carroll Naish) struggles to keep the star lit, hoping its brilliant light will catch the eye of highway travelers for miles around.

The camera takes us there long before the cowboys have time to arrive. It turns out the star the cowboys see is no astronomical phenomenon; it’s an advertising sign, illuminated by 102 light bulbs. Recently purchased from a defunct movie theater (“Star Picture Palace”), it’s been newly installed over a roadside inn, the Star Auto Court. As a lone vagabond approaches from the road, the Star’s proprietor, Nick Catapoli (J. Carroll Naish) struggles to keep the star lit, hoping its brilliant light will catch the eye of highway travelers for miles around.

My late uncle remembered seeing Star in the Night as a 15-year-old and being deeply impressed. He wasn’t alone; at the Academy Awards Ceremony in Grauman’s Chinese Theatre on March 7, 1946, Star‘s producer Gordon Hollingshead took home the Oscar for the best two-reel short subject of 1945. After that, Star in the Night simply dropped off the face of the earth and was as utterly forgotten as any film of the sound era has ever been. Myself, I had never heard of it before I stumbled across a 16mm print up for auction on eBay in 2008. The listing piqued my interest, and a follow-up check of the IMDb was an eye-opener: J. Carroll Naish?? Irving Bacon?? Dick Elliott?? Richard Erdman?? Don Siegel??? Academy Award?!?

My late uncle remembered seeing Star in the Night as a 15-year-old and being deeply impressed. He wasn’t alone; at the Academy Awards Ceremony in Grauman’s Chinese Theatre on March 7, 1946, Star‘s producer Gordon Hollingshead took home the Oscar for the best two-reel short subject of 1945. After that, Star in the Night simply dropped off the face of the earth and was as utterly forgotten as any film of the sound era has ever been. Myself, I had never heard of it before I stumbled across a 16mm print up for auction on eBay in 2008. The listing piqued my interest, and a follow-up check of the IMDb was an eye-opener: J. Carroll Naish?? Irving Bacon?? Dick Elliott?? Richard Erdman?? Don Siegel??? Academy Award?!?

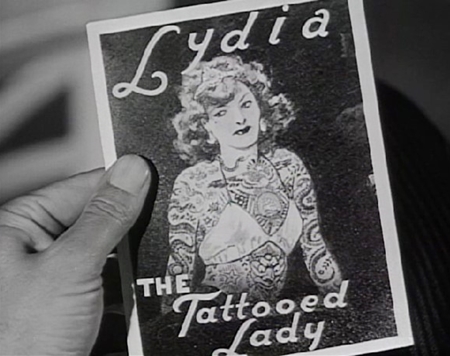

At the moment, I’m in rehearsals for a stage production of Pride and Prejudice, Jane Austen’s 1813 romantic comedy of manners chronicling the romantic vicissitudes of five English sisters. The youngest and silliest of these sisters is named Lydia — which naturally put me in mind of “Lydia the Tattooed Lady”. I say naturally, because once anyone has heard that song — especially as done by the Marx Brothers cavorting in a railroad car in At the Circus (1939) — it’s impossible not to think of it whenever the name “Lydia” is mentioned. It doesn’t matter if the subject is the Iron Age kingdom of Lydia in Asia Minor; Lydia Pinkham, the 19th century American purveyor of ladies’ patent medicines; St. Lydia of Thyatira; Lydia Becker, the British suffragette; Kenneth Roberts’s novel Lydia Bailey; or the youngest daughter in Pride and Prejudice. No matter what, if you hear or read the name “Lydia”, you automatically fill in with “…the Tattooed Lady”.

At the moment, I’m in rehearsals for a stage production of Pride and Prejudice, Jane Austen’s 1813 romantic comedy of manners chronicling the romantic vicissitudes of five English sisters. The youngest and silliest of these sisters is named Lydia — which naturally put me in mind of “Lydia the Tattooed Lady”. I say naturally, because once anyone has heard that song — especially as done by the Marx Brothers cavorting in a railroad car in At the Circus (1939) — it’s impossible not to think of it whenever the name “Lydia” is mentioned. It doesn’t matter if the subject is the Iron Age kingdom of Lydia in Asia Minor; Lydia Pinkham, the 19th century American purveyor of ladies’ patent medicines; St. Lydia of Thyatira; Lydia Becker, the British suffragette; Kenneth Roberts’s novel Lydia Bailey; or the youngest daughter in Pride and Prejudice. No matter what, if you hear or read the name “Lydia”, you automatically fill in with “…the Tattooed Lady”.

She was the most glo-o-o-rious creature under the sun,

She was the most glo-o-o-rious creature under the sun,

For a dime you can see Kankakee

For a dime you can see Kankakee Up the hill comes Andrew Jackson

Up the hill comes Andrew Jackson With a view of Niag’ra

With a view of Niag’ra

Come along and see Buff’lo Bill

Come along and see Buff’lo Bill La la la-a-a-a-a, la la la

La la la-a-a-a-a, la la la The ships on her hips made his heart skip a beat,

The ships on her hips made his heart skip a beat,

The final day of Columbus Moving Picture Show 2023 opened, naturally enough, with the final four chapters of The Purple Monster Strikes. Our slow-on-the-uptake hero, slugging-and-shooting attorney Craig Foster (Dennis Moore) finally begins to catch on that something’s not right with “Dr. Layton” (who is in fact the Purple Monster, having murdered Dr. Layton and taken over his body). Back in Chapter 11 the Emperor of Mars sent a female underling to assist the Purple Monster by killing one of the secretaries at the “jet plane” factory and taking over her body. By the way, oddly enough, when the Purple Monster arrives on Earth, he tells his hired Earthling thug, “My name would mean nothing to you; you can call me the Purple Monster.” But the female sent to aid him is named Marcia before she takes over the body of Helen. Do only women on Mars have simple names? Or is “Marcia the Martian” an alias? If so, why didn’t the Purple Monster just call himself “Martin”, like Ray Walston on 1960s TV? Then again, Martin Strikes wouldn’t have been a very dramatic title. Well, anyhow, Marcia was a little sloppy while vacating Helen’s body, and the late Dr. Layton’s niece Sheila (Linda Stirling), feigning unconsciousness, observed her in the act. This enabled Foster finally to put two and two together and plant a camera in “Dr. Layton’s” office to see if he’s doing the same thing. But even before the film is developed, the Purple Monster makes his move, absconding with the prototype “jet plane” to be reverse-engineered back on Mars. Fortunately, Foster turns the “annihilator ray” on the escaping Purple Monster and blows him out of the sky (another nifty miniature by the Lydecker Brothers). And Chapter 15 ends with the unspoken hope that future extraterrestrial invaders will be no smarter than this one was. There would in fact be three more such invasions courtesy of Republic Pictures in the next seven years, all of them outsourcing groundwork of the invasion to local muscle: Flying Disc Man from Mars (1951), Radar Men from the Moon and Zombies of the Stratosphere (both ’52), all three featuring stock footage from Purple Monster and other Republic serials. Maybe we’ll see one or more of those at future Picture Shows.

The final day of Columbus Moving Picture Show 2023 opened, naturally enough, with the final four chapters of The Purple Monster Strikes. Our slow-on-the-uptake hero, slugging-and-shooting attorney Craig Foster (Dennis Moore) finally begins to catch on that something’s not right with “Dr. Layton” (who is in fact the Purple Monster, having murdered Dr. Layton and taken over his body). Back in Chapter 11 the Emperor of Mars sent a female underling to assist the Purple Monster by killing one of the secretaries at the “jet plane” factory and taking over her body. By the way, oddly enough, when the Purple Monster arrives on Earth, he tells his hired Earthling thug, “My name would mean nothing to you; you can call me the Purple Monster.” But the female sent to aid him is named Marcia before she takes over the body of Helen. Do only women on Mars have simple names? Or is “Marcia the Martian” an alias? If so, why didn’t the Purple Monster just call himself “Martin”, like Ray Walston on 1960s TV? Then again, Martin Strikes wouldn’t have been a very dramatic title. Well, anyhow, Marcia was a little sloppy while vacating Helen’s body, and the late Dr. Layton’s niece Sheila (Linda Stirling), feigning unconsciousness, observed her in the act. This enabled Foster finally to put two and two together and plant a camera in “Dr. Layton’s” office to see if he’s doing the same thing. But even before the film is developed, the Purple Monster makes his move, absconding with the prototype “jet plane” to be reverse-engineered back on Mars. Fortunately, Foster turns the “annihilator ray” on the escaping Purple Monster and blows him out of the sky (another nifty miniature by the Lydecker Brothers). And Chapter 15 ends with the unspoken hope that future extraterrestrial invaders will be no smarter than this one was. There would in fact be three more such invasions courtesy of Republic Pictures in the next seven years, all of them outsourcing groundwork of the invasion to local muscle: Flying Disc Man from Mars (1951), Radar Men from the Moon and Zombies of the Stratosphere (both ’52), all three featuring stock footage from Purple Monster and other Republic serials. Maybe we’ll see one or more of those at future Picture Shows. The Unknown Soldier (1926)

The Unknown Soldier (1926) At this point — in the home stretch, as it were, and within sight of the finish line — The Picture Show was hit by a one-two punch of bad luck: The next two features on the program had to be replaced by unscheduled substitutes. First to go was I Can’t Give You Anything But Love, Baby (1940), a Universal B-musical starring Broderick Crawford as a gangster with songwriting ambitions who kidnaps a young composer to collaborate with. I have a soft spot for Classic Era B-musicals, and for Broderick Crawford in the days when he still looked like his mother Helen Broderick, but the print arrived with an advanced case of vinegar syndrome (a “disease” that can reduce an acetate-based print to a pile of warped, brittle substance reeking of salad dressing) and had been rendered unusable. I was disappointed, but then again

At this point — in the home stretch, as it were, and within sight of the finish line — The Picture Show was hit by a one-two punch of bad luck: The next two features on the program had to be replaced by unscheduled substitutes. First to go was I Can’t Give You Anything But Love, Baby (1940), a Universal B-musical starring Broderick Crawford as a gangster with songwriting ambitions who kidnaps a young composer to collaborate with. I have a soft spot for Classic Era B-musicals, and for Broderick Crawford in the days when he still looked like his mother Helen Broderick, but the print arrived with an advanced case of vinegar syndrome (a “disease” that can reduce an acetate-based print to a pile of warped, brittle substance reeking of salad dressing) and had been rendered unusable. I was disappointed, but then again  Instead we got

Instead we got  The day and the weekend wound up with

The day and the weekend wound up with

Nick Santa Maria — not only Benny Biffle of Michael Schlesinger’s 1930s-style

Nick Santa Maria — not only Benny Biffle of Michael Schlesinger’s 1930s-style  Also in the cast was band singer Carol Bruce, whose movie career never really took off, but who was good enough to deserve better breaks. All through the screening I struggled to figure out why she looked so familiar, but it never came. It wasn’t until later, reading Dave Domagala’s program notes, that I got my answer: From 1978 to ’82 she had a recurring role on WKRP in Cincinnati as Lillian Carlson, the flinty station owner and mother of manager Arthur Carlson (Gordon Jump). I would never have figured that out on my own, but now that I know, I can see it. The eyes, I think, are a bit of a giveaway.

Also in the cast was band singer Carol Bruce, whose movie career never really took off, but who was good enough to deserve better breaks. All through the screening I struggled to figure out why she looked so familiar, but it never came. It wasn’t until later, reading Dave Domagala’s program notes, that I got my answer: From 1978 to ’82 she had a recurring role on WKRP in Cincinnati as Lillian Carlson, the flinty station owner and mother of manager Arthur Carlson (Gordon Jump). I would never have figured that out on my own, but now that I know, I can see it. The eyes, I think, are a bit of a giveaway. I sure didn’t miss the next screening, and boy, am I glad, because this was another highlight of the whole weekend — for me at least, and I’m pretty sure I’m not alone (witness the fact that a poster for it graced the cover of The Picture Show’s program book). The picture, introduced by author and historian James D’Arc, was

I sure didn’t miss the next screening, and boy, am I glad, because this was another highlight of the whole weekend — for me at least, and I’m pretty sure I’m not alone (witness the fact that a poster for it graced the cover of The Picture Show’s program book). The picture, introduced by author and historian James D’Arc, was  Either Philip Carli or David Drazin — sorry, I forget which — was pressed back into service for

Either Philip Carli or David Drazin — sorry, I forget which — was pressed back into service for  The Turning Point

The Turning Point Day 3 wrapped up with

Day 3 wrapped up with