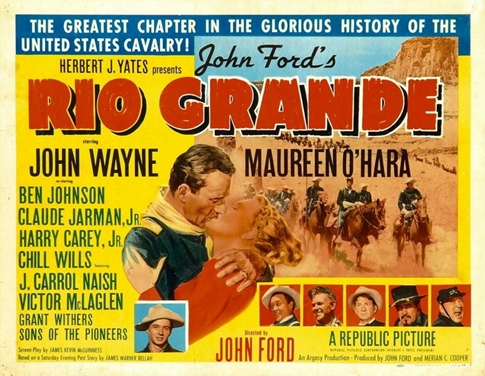

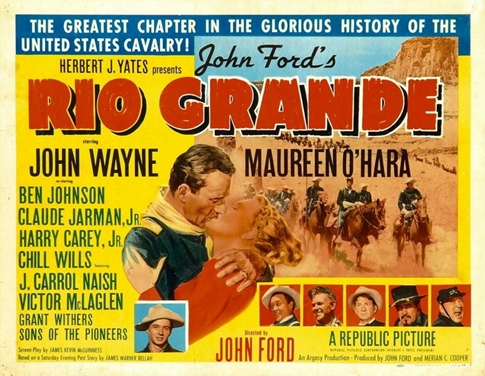

On March 3, 2017, Claude Jarman Jr. welcomed my friend Richard Glazier and me into his beautiful hillside home in Kentfield, Marin County, Calif., 17 miles north of San Francisco. There he sat down with us for a nice long talk about his life and Hollywood career, touching upon (among other things) his portrayals of the three characters named in the title of this post: Jody Baxter, the backwoods youth coming of age in Clarence Brown’s 1946 movie of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’s Pulitzer Prize novel The Yearling; Chick Mallison, a Mississippi boy confronting racism (including his own) when an African American friend is accused of murdering a white man in another Clarence Brown film, William Faulkner’s Intruder in the Dust (1949); and Trooper Jeff Yorke, a frontier horse soldier torn between his estranged parents, Lt. Col. Kirby Yorke (John Wayne) and Kathleen (Maureen O’Hara) in Rio Grande (1950), the last of John Ford’s “Cavalry Trilogy” (after Fort Apache [’48] and She Wore a Yellow Ribbon [’49]).

On March 3, 2017, Claude Jarman Jr. welcomed my friend Richard Glazier and me into his beautiful hillside home in Kentfield, Marin County, Calif., 17 miles north of San Francisco. There he sat down with us for a nice long talk about his life and Hollywood career, touching upon (among other things) his portrayals of the three characters named in the title of this post: Jody Baxter, the backwoods youth coming of age in Clarence Brown’s 1946 movie of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’s Pulitzer Prize novel The Yearling; Chick Mallison, a Mississippi boy confronting racism (including his own) when an African American friend is accused of murdering a white man in another Clarence Brown film, William Faulkner’s Intruder in the Dust (1949); and Trooper Jeff Yorke, a frontier horse soldier torn between his estranged parents, Lt. Col. Kirby Yorke (John Wayne) and Kathleen (Maureen O’Hara) in Rio Grande (1950), the last of John Ford’s “Cavalry Trilogy” (after Fort Apache [’48] and She Wore a Yellow Ribbon [’49]).

I feel certain this was the last time Mr. Jarman (who passed away on January 12 at the age of 90) sat for such an in-depth interview; indeed, I think it may have been the only time, unless he participated in a discussion with Robert Osborne or Ben Mankiewicz and an audience Q&A during one of his appearances at the Turner Classic Movies Film Festival in Hollywood. In any event, it was a rare privilege for me — less rare for Richard, who has been diligently compiling interviews with survivors of Hollywood’s Golden Years, but just as much of a privilege. In memory of Mr. Jarman’s openness, graciousness and good humor (and with gratitude to Richard for his permission), I’m pleased to share it now with Cinedrome readers. I have made minor edits for clarity and to minimize extraneous “ums”, “ers”, and “y’knows”, and I have added explanatory notes in italicized brackets where appropriate; otherwise, this is Mr. Jarman exactly as we found him back in 2017.

* * *

RICHARD GLAZIER (RG): Could you tell us, Claude, where you were born and just a little about your upbringing and your parents?

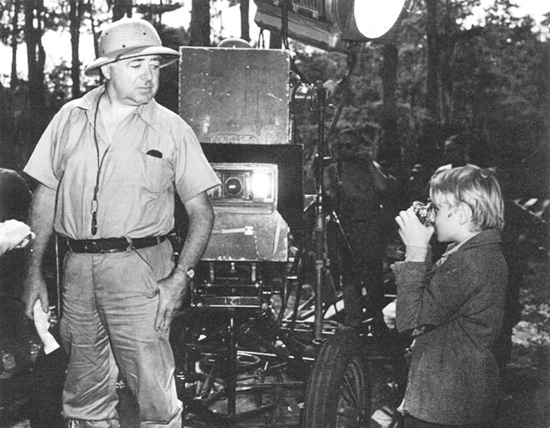

CLAUDE JARMAN JR. (CJ): Okay. I was born in Nashville, Tennessee. Grew up there, stayed there until I was 10 years old. It was that year that I was picked out of a schoolroom by Clarence Brown and shuffled off to Hollywood to be in The Yearling. Clarence, when he took on that assignment from L.B. Mayer, was determined to have a young boy who was not from Hollywood, he wanted a southern blond-haired kid to play that role, and went out on his own with his production manager to different cities in the South looking for someone to play that role, and he saw me. So he took me basically on looks alone and figured he could get the kind of role out of me, or performance…

RG: So did you have no acting experience at all?

CJ: Well, ten years old, I was in school plays and little theater, I was doing that, so I did have an interest in acting.

JIM LANE (JL): When he showed up in your classroom did you know what he was there for?

JIM LANE (JL): When he showed up in your classroom did you know what he was there for?

CJ: No, no. He would go into a city, he would go to the office of the superintendent, identify himself, and say, “I would like a letter that I can go into the schools in Nashville, into the grammar schools, and give this to the principal, and be able to look around the fifth and sixth grade rooms, and if I see anybody I want to talk to, I’d like to be able to do that. And if I don’t, no one ever knew I was there.” And that’s the way he operated. In doing that, he went throughout — to Memphis, Nashville, Knoxville, Atlanta…

RG: Are we talking about Clarence Brown?

CJ: Talking about Clarence Brown.

RG: He came himself?

CJ: He came himself. He was determined to find the boy that he was looking for. And he took it on. He was not satisfied — the talent scouts had been out to these various cities, putting an ad in the paper, if your kid is, you know, ten years old, blah blah blah. And he was getting nothing he liked. He was getting kids twenty years old showing up.

JL: How did your parents respond to this?

CJ: Well, it was kind of a shock.They didn’t believe what was gonna happen. They just said…after he saw me, two weeks later I got a call saying, “Can you come to Hollywood and make a test?” My father was working for the railroad at that time, and he took a two-week vacation, said, “We’ll go to Hollywood, and if nothing happens we’ll come back — “

JL: The worse that could happen is you get a vacation.

CJ: Exactly. That’s exactly what we did.

RG: So you did a screen test when you went to Hollywood…

CJ: You know what? I never did a screen test.

RG: So tell us about that.

CJ: Well, there were like five or six other boys that had been brought in, and we were all at the MGM school. And the only thing I ended up doing was taking a screen test with potential actresses who would play the mother. So I would do a screen test with them, ’cause they were looking for the Jane Wyman or, you know, whatever that was gonna get that role.

JL: So they wound up with Jane Wyman. Do you remember who the others were?

CJ: Well there was one named Jacqueline White who got the role. People don’t even know this, but Jackie White was the mother, she went to Florida, where we worked for three months. And when we got back to Hollywood they thought that she was really too young, she was only in her twenties, and they thought she just didn’t look mature enough to play the mother, so they replaced her with Jane Wyman. Which also meant that we had to go back and do some retakes using her instead of Jackie. [NOTE: This was news to me, and may even be a bit of a scoop. Jacqueline White — best remembered today for Richard Fleischer’s noir classic The Narrow Margin (1952) — was young indeed, only 22 when she went to Florida for The Yearling. Ms. White is still with us — she’ll be 103 next Thanksgiving — and hopefully some enterprising researcher will look her up to learn what she remembers of her work on the picture.]

CJ: Well there was one named Jacqueline White who got the role. People don’t even know this, but Jackie White was the mother, she went to Florida, where we worked for three months. And when we got back to Hollywood they thought that she was really too young, she was only in her twenties, and they thought she just didn’t look mature enough to play the mother, so they replaced her with Jane Wyman. Which also meant that we had to go back and do some retakes using her instead of Jackie. [NOTE: This was news to me, and may even be a bit of a scoop. Jacqueline White — best remembered today for Richard Fleischer’s noir classic The Narrow Margin (1952) — was young indeed, only 22 when she went to Florida for The Yearling. Ms. White is still with us — she’ll be 103 next Thanksgiving — and hopefully some enterprising researcher will look her up to learn what she remembers of her work on the picture.]

JL: So you actually did two stints on location.

CJ: Yes. Although most of it —

JL: Three months the first time; how long the second time?

CJ: Well, the first time, most of the shots that we made in Florida were with the animals and with Gregory Peck. They were not with – only very few scenes [with the mother], so they really didn’t have to redo too many things to do that. But we did take two trips to Florida because we got rained out the first time.

RG: They had to pack it up and come home, didn’t they?

CJ: In August. It rained for one month.

RG: So they were just on standby, losing lots of money, so they said to come home.

CJ: Let’s go home, go back in January and do the makeup.

JL: How much, would you guess, in terms of the time you spent but also in terms of what’s in the final film, how much was shot in Florida and how much was shot back at the studio?

CJ: Well, all the interiors were shot in the studio. The scenes in the town were shot at Lake Arrowhead, and the rest, all the other outside stuff was shot in Florida. So I would say probably half.

RG: I remember you telling me that after the shoot you kind of emotionally collapsed, that you were so exhausted; was that correct? That you’d put so much energy into it.

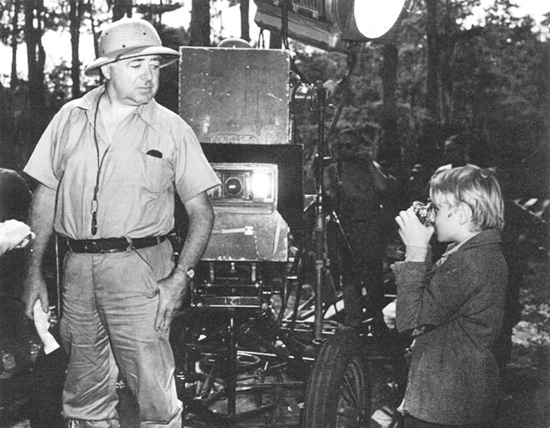

CJ: Well, I was ten when we started and I was 12 by the time it came out, so that was a long period to deal with one particular work. It was exhausting, it really was exhausting. Clarence Brown was an exhausting director because he was a perfectionist. Whereas today, most films, you know, you take two or three takes and that’s it, I would say our average over the course of that film was at least 20. Twenty times we would do a scene. And then he would always do long shot, medium shot, close-up, over the shoulder, so you would spend a whole day doing one scene. So it was exhausting. And then you were dealing with animals, and you cannot train a deer, you’d have to wait until the deer did what it was supposed to do. And it was hard.

RG: Talk about your relationship with Clarence Brown, what that was like.

RG: Talk about your relationship with Clarence Brown, what that was like.

CJ: Well, he basically took over the role as my father. I mean, I was with him all the time, I was with him every night, talking about the scenes for the next day. He was my mentor and he was the person who devoted all his time to me. He didn’t worry about Gregory Peck or Jane Wyman, you know, they were professional, but he was just determined to get the performance out of me.

RG: And he was kind to you…

CJ: Oh yeah.

RG: …and nurturing…

CJ: He was nurturing, but he had a temper too, you know, he’d get upset if things didn’t go well.

RG: Did he ever lose his temper at you?

CJ: Not really, he’d just lose his temper at…[Chuckles] anything that was going on, and just get frustrated.

RG: Were you scared of him?

CJ: No. Good question!

RG: Did you feel a lot of pressure playing those scenes with Gregory Peck and Jane Wyman?

CJ: No, because they were so easy to work with, I mean I was amazed at how easy, particularly, Gregory Peck was. ‘Cause he was the one I was in with more than with Jane Wyman. He was very patient. And he was young, he was just kind of coming into his own. He’d made, what, Keys of the Kingdom, and had just made Duel in the Sun, which had not come out yet. But he was just beginning to take off as a big actor. But he’s a young guy, I mean, how old was Gregory, 29, 30 at that time? He was young. [NOTE: Peck turned 29 during shooting.]

RG: Would you say you learned by watching them act? Did it make you a better actor by watching these guys?

CJ: Maybe, but I don’t think of it in those terms. I just think of trying to hold my own and be responsive.

RG: Did you have to memorize your lines and have the script all memorized?

CJ: I would say that for two or three years afterwards I could tell you every line in that film.

JL: Did you ever have to deal with rewrites or anything like that, did they ever spring new scenes on you?

CJ: No.

JL: So it was pretty much what you got at the beginning…

CJ: Pretty much.

RG: Did the authoress of The Yearling come on the set at all?

CJ: No. Marjorie Rawlings? No. I never met her. I don’t know whether she got along with Clarence. I don’t think she ever came on, I don’t think he ever went over to her. I think she was maybe involved when they first tried to make the movie in 1939, but she probably just kind of washed her hands of it after that. Unlike Intruder in the Dust where William Faulkner was on the set all the time.

RG: We’ll get to that, we want to hear all about that. Now we want to move on to The Sun Comes Up. That’s a very interesting film in that, of course, it’s the last film that Jeanette MacDonald ever did, the first score of André Previn. Can you talk a little about what it was like to work with the legendary Jeanette MacDonald?

CJ: Well, she had dropped out, I guess, of making films for quite a time and this was her return. Sun Comes Up was based on a story by Marjorie Rawlings and they were hopefully going to do a “remake of The Yearling” type thing, but to me it was not that successful. I thought it was — I didn’t have a lot of enthusiasm for it, I thought the director was…

RG: Richard Thorpe.

CJ: Richard Thorpe was one of these guys who finishes on time. Unlike Clarence, where you really get into a film and emotion, I didn’t feel that way at all about him. And they didn’t spend a lot of money on it. Supposed to have been, the setting was North Carolina, it was actually Santa Cruz. So you could tell they didn’t — they downsized the whole thing.

RG: What was Jeanette MacDonald like?

CJ: She was a lovely person.

RG: Was she not well during the production?

CJ: I think she seemed all right. She seemed a little fragile.

RG: What was it like working with Lassie?

CJ: Lassie bit me in the face, so I got mad.

CJ: Lassie bit me in the face, so I got mad.

RG: Was Rudd Weatherwax controlling, training him at the time?

CJ: Yeah.

RG: And he bit you in the face. Do you remember the scene where he bit you?

CJ: Yeah, I remember it was kind of a close up, and I was putting his neck up close and he goes [lunges forward, snaps his teeth] and everyone went, “Aaaahh!” I had to make up my cheek for the next —

RG: On the shoot did you get to meet Lewis Stone?

CJ: No.

RG: You never because he just played that little cameo at the beginning as her manager.

CJ: Right. And then there was Percy Kilbride.

RG: Oh God, what a strange character he was. He was a little bit much in that movie I think.

CJ: It was…I was never that happy with that movie for some reason.

RG: Did you feel that way even during the filming?

CJ: Yeah, I did.

RG: So you didn’t have an enthusiasm, and Richard Thorpe was just very businesslike.

CJ: Yeah. Exactly. And he made, you know, 50 movies. [NOTE: In fact, Richard Thorpe has 189 directing credits on the IMDb.]

RG: He made, like, Athena with Jane Powell…

JL: He’s like the classic studio hack.

CJ: Yeah, exactly. He was there. Here’s your schedule, finish it on time, let’s move on. That was the way it worked.

RG: But Jeanette sang some beautiful arias in the film. She was such a great star.

CJ: Yeah. But see, I never saw that, ’cause she was there, she was in the house, or she was in New York. So the only time she saw me I was in the orphanage, it wasn’t a —

RG: You played some scenes in the car with her as well.

CJ: Yeah, yeah.

RG: But it was not a successful film.

CJ: No.

RG: And I feel that André Previn made a very — He was only 18 or 19 years old at the time when he wrote the score — and it’s a very lush score. The score itself, the movie music, seems a little out of character for the film.

CJ: Oh really?

RG: I felt that anyway because it’s very lush, a very romantic kind of thing.

CJ: The MGM orchestra.

RG: Yeah, exactly. Did you meet André Previn?

CJ: Yeah, I did meet him. ‘Cause he was there a number of years, right?

RG: Oh yeah.

CJ: So I met him off and on when I was at the studio there for five years.

RG: Did you ever go into L.B.’s white office with the big white desk?

CJ: Sure.

RG: Did you ever eat in the commissary with him?

CJ: Not with him. They had a little private room off to the side that the execs would have lunch.

RG: Were you afraid of him when you were in his presence?

CJ: No.

RG: Was he nice to you?

CJ: Yeah.

RG: He didn’t curse in front of you or anything like that?

CJ: [Laughs] No. I never knew any of that till I started reading about him, reading books about him.

JL: Apparently he was great with kids.

CJ: Yeah, he was a real family-oriented guy.

RG: That’s why he loved Andy Hardy so much.

CJ: Yeah, he was — as you say, he loved kids, that was his…he was a strange, strange man, you know?

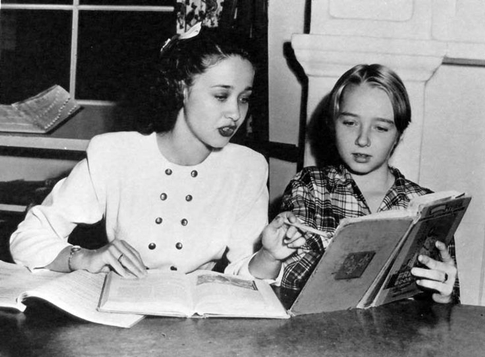

RG: Can you talk a little about the schoolhouse?

CJ: Well…

RG: Did you have Miss McDonald, was that her name?

CJ: Miss McDonald, Mary McDonald.

RG: How about that, I remembered the teacher’s name. Margaret O’Brien told me.

CJ: Did she really?

RG: Miss McDonald.

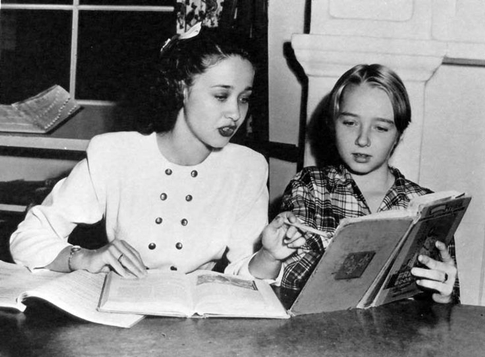

CJ: Well, you know, Margaret — I still see her occasionally. At the MGM school when I first started there in 1945, there were maybe, I would say twelve kids, ranging from second grade to high school. And we had first-to-eighth grade was in was one room, nine-to-twelve was in another room, so we had a teacher for each room, and Miss McDonald was the principal. It was like every one, you know, a little, small school. And we all had to go to school for three hours a day, nine to twelve. That was all schooling, though. When you consider how kids go to high school, how many — you probably don’t spend more than three hours in intense work; here you spent three hours actually studying. Then after that you go, and then of course you’re making a film, and you have a tutor, you have somebody who’s working with you, and you still have to get your three hours of schooling in. Except you get it in — like on The Yearling I would get ten minutes at a time.

RG: Who was in your class?

RG: Who was in your class?

CJ: Dean Stockwell, his brother Guy, Elizabeth Taylor, Jane Powell, Anne Francis I think.

RG: Was Darryl Hickman with you?

CJ: No.

RG: He was a little bit younger than you I think.

CJ: Yeah, I think so. He was not — We had some kids who would come when they were working for, just signed for — not under contract, but just be working, and when they have a day off they’d go to school there.

RG: So when you were on a shoot — let’s say when you were making The Sun Comes Up, what was a typical day for Claude Jarman Jr. during production? What time would you get up, that kind of thing, be at the studio, makeup and all that?

CJ: Well, you still have certain time restrictions. If you were really heavily involved, had a lot to do in a film — like in The Yearling I think I was in every scene — you had to have your schoolwork done by four in the afternoon. So if you reach one o’clock and you still have two hours of school to go, they shut it down. Everything has to shut down while you go to school. So it was very hard for me to do that, because while I’m in school everyone’s getting a break, and then when four o’clock comes I gotta go to work, so I don’t get any break. So when I made those films, like Intruder and whatever, then there was always a school commitment. And I was very lucky in a number of these films, particularly the westerns that were made in the summertime so there was no school. So I looked forward to filming in the summer so you didn’t have to worry about it. But it was hard to get in three hours a day when you’re really in a lot of the scenes.

RG: And makeup? How long would it take you to get into makeup and all that?

CJ: I would say the only time I ever wore makeup was The Sun Comes Up and High Barbaree where I played Van Johnson [as a youngster] where they put freckles on my face.

RG: So it didn’t take that long.

CJ: No. You know, I had no makeup in most — Intruder in the Dust I wore no makeup.

RG: Now, after The Sun Comes Up your next film I believe was Intruder in the Dust in 1949.

CJ: Yeah.

RG: Can you tell us how that became — That was a pet project of Clarence Brown, correct? Because Clarence Brown and L.B. were very good friends, is that correct too? I mean, correct me if I’m wrong.

CJ: They were business partners and good friends.

RG: And they owned tons of land, they were both of them very wealthy. He was a land-owner, wasn’t he, Clarence Brown?

CJ: Yeah, they owned a lot of land in the San Fernando Valley and then they ended up buying a lot of land down in the Palm Springs area.

RG: So tell us about Intruder in the Dust and how it came about.

CJ: Well, I know that Clarence was familiar with this and he really wanted to make this film. He never said this, but I’d read that he had been in Atlanta when there was some sort of a hanging or something, something that went on that upset him, and he always wanted to make that film. And he went to L.B. Mayer and L.B. Mayer said no. He said, “We’re doing all these musicals, we do all this wonderful stuff, why do we want to get involved in a film that deals with a lynching? And particularly with a black person, we’re just not ready for that.” And Clarence prevailed, he said, “I really want to do this.” And at that time Dore Schary was also at the studio, and Schary really wanted to do it also. So they said, “Okay, you can do it.” Probably, once it was finished, they didn’t know what to do with it. They really didn’t. They sort of buried it. It was getting great reviews in London, people were loving it, they thought it would be a possible nomination for an Academy Award. But in those days the studios would put forth the films that they wanted to be Academy Award projects; Fox would have one, Warner Bros. would have one, Paramount. And MGM did not want to put forth Intruder; they put forth, I think, Battleground or some war movie at that time. So the film did not make any money, and it just went away.

CJ: Well, I know that Clarence was familiar with this and he really wanted to make this film. He never said this, but I’d read that he had been in Atlanta when there was some sort of a hanging or something, something that went on that upset him, and he always wanted to make that film. And he went to L.B. Mayer and L.B. Mayer said no. He said, “We’re doing all these musicals, we do all this wonderful stuff, why do we want to get involved in a film that deals with a lynching? And particularly with a black person, we’re just not ready for that.” And Clarence prevailed, he said, “I really want to do this.” And at that time Dore Schary was also at the studio, and Schary really wanted to do it also. So they said, “Okay, you can do it.” Probably, once it was finished, they didn’t know what to do with it. They really didn’t. They sort of buried it. It was getting great reviews in London, people were loving it, they thought it would be a possible nomination for an Academy Award. But in those days the studios would put forth the films that they wanted to be Academy Award projects; Fox would have one, Warner Bros. would have one, Paramount. And MGM did not want to put forth Intruder; they put forth, I think, Battleground or some war movie at that time. So the film did not make any money, and it just went away.

JL: That one looks to me like it was shot entirely on location.

CJ: It was.

JL: Did you do anything at all back at the studio?

CJ: Oh, maybe one or two things…

JL: It all looks really authentic.

RG: And wasn’t Mr. [Juano] Hernández nominated for a Golden Globe, is that correct?

CJ: Yes.

JL: Best Newcomer or something like that.

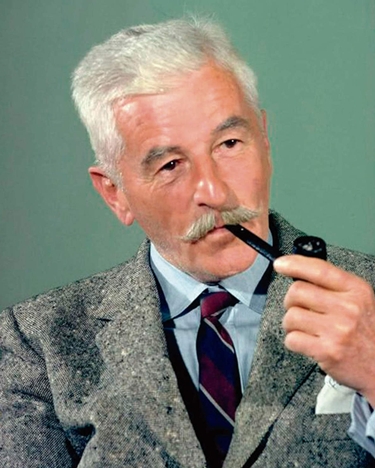

RG: Tell us about William Faulkner; he came on the set?

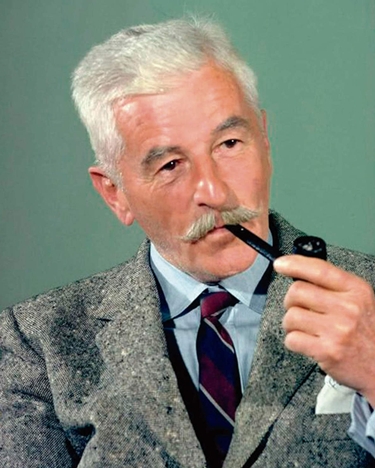

CJ: He would come on the set, he and Clarence would talk a lot. Faulkner had a daughter, Jill [1933-2006], who I knew, and we would go out to parties at his house. I was 15, 16, and I got to know a lot of the kids down in Oxford, and I had a great time there. And Clarence was much more relaxed than he had been on The Yearling; he wasn’t under the pressure that he was.

JL: It was a smaller film, less of a burden.

CJ: Exactly. There was nothing, we didn’t worry — And what’s interesting was, you’d appreciate this, with The Yearling we had so much difficulty getting the soundtrack, particularly in the outdoors with the snapping of tree limbs when you’d be walking around. How many times we had to keep doing it, and Clarence just got so frustrated that when he did Intruder in the Dust he said, “We’re gonna shoot this with an open camera and we’re gonna come back to the studio and we’re gonna dub the whole film.”

JL: I did notice that. So it was all, that was post-dubbed.

CJ: Yeah. And the problem was, in The Yearling, a lot of The Yearling we had to re-loop also because of the sound. He said, “I don’t want to do this anymore.”

RG: Too much outside noise.

CJ: Yeah. So he just said we’ll — ’cause when you’re doing, as you know, when you’re doing like a documentary type, you go into that jail in Oxford and all, you don’t need — you don’t have these huge cameras, you end up — It was more like you have cameras today. We would get in there and he would just say, “Let’s just get [it without] the soundtrack and get out of here. We’ll worry about it later.”

JL: Was it difficult post-dubbing all that dialogue?

CJ: Yeah, it is, ’cause you’re doing it one line at a time. It’s funny, ’cause he talked about, he said that Hepburn and Tracy both hated dubbing, they just thought it was terrible. He said, “Well, let me go show you a film,” and he showed them Intruder and he said, “What do you think?” They said, “Oh, it’s great, Clarence.” “This whole film was just dubbed.”

RG: They couldn’t even tell.

CJ: No.

RG: Now what kind of person was Faulkner? Was he quiet, was he — ?

RG: Now what kind of person was Faulkner? Was he quiet, was he — ?

CJ: [Laughing] Very quiet. He never said anything unless you said something to him.

RG: Was he shy, or just — ?

CJ: Yeah. He always smoked a pipe. I saw him at an airport maybe two years later. I was flying to California from Nashville and he’d gotten off a plane from New York. “Hi, Mr. Faulkner, how are you?” “I’m fine.” [Pause] “Well…how’s Oxford?” “Oxford’s just doing very well.” [Slightly longer pause] “Well, nice to see you, Mr. Faulkner.” “Good to see you.”

RG: And that was it.

CJ: [Chuckling] That’s it.

JL: I also heard, and I don’t know if this is true, that he did some uncredited rewrites on the script.

CJ: Could be.

JL: Do you know anything about that?

CJ: No, but I wouldn’t be surprised if there were some changes.

RG: Like we said, that moving, beautiful speech from when he won the Nobel Prize…

CJ: Oh yeah, yeah.

RG: It just makes you want to weep, it’s so profound.

CJ: Yes, he was a very special, special person.

RG: An American treasure, absolutely. Now did you know when you were making Intruder in the Dust that you were onto something very special there?

CJ: Yeah, I did. I thought it was — You know, growing up in the South I was used to segregation, it was just a way of life. When we made Intruder it was — Juano Hernández stayed in a private home, he could not stay in the hotel. So that’s what we were still dealing with. It was only two or three years later when they had a big riot at the University of Mississippi and somebody got killed. James Meredith got into the school and Oxford blew up. [NOTE: Actually, Meredith’s enrollment at the University of Mississippi and the notorious “Ole Miss riot” both occurred in 1962, 13 years after this.] But you did not sense that in 1949 when we were making the movie. I mean, the mayor and everybody was in the movie.

RG: It’s so interesting to see your character, even as a teenager, transform. You had that [murder victim’s] father [played by Porter Hall] barking those terrible things at you, and then you had the uncle [David Brian] who transformed your character. It’s just very, very powerful.

CJ: And he kind of transformed his character too.

RG: Exactly.

CJ: ‘Cause he learned a lot in that story also.

RG: And it’s very interesting, in 1949 you mentioned Dore Schary. Schary wasn’t running the studio in ’49, is that correct?

CJ: No, you know, they were both running it, and that was the problem.

RG: That’s probably part of the reason, because Schary was very much a politically aware, he was liberal and he was very —

JL: A social justice warrior.

RG: I mean, Jill Schary [Dore’s daughter, 1936-2024] told me that he would’ve probably sacrificed his life in a wheelchair to be Franklin Delano Roosevelt. We interviewed her about Dore. He just worshiped FDR.

CJ: He was definitely of a new school as opposed to the old school in filmmaking.

RG: Then you went on to make The Outriders (1950). You were on loan for that, is that correct?

RG: Then you went on to make The Outriders (1950). You were on loan for that, is that correct?

CJ: No, that was an MGM film. I think that was the last picture I made while I was at MGM. Everything else was…

RG: Can you tell us a little about that, tell us about Joel McCrea? You worked as a child with some of the greatest actors of the 20th century. I mean, my gosh the great actors — which is a tribute to your talent as well, of course.

CJ: It was — Problem with The Outriders, if you noticed, I didn’t really have a huge part of it.

RG: But still you were with James Whitmore, Ramon Navarro. What was Navarro like?

CJ: He was a very quiet kind of guy. He was very shy, came across as being that. We made it in Kanab, Utah, which is just at the upper Grand Canyon area. Beautiful, absolutely beautiful country.

RG: Arlene Dahl was so pretty in that movie, wasn’t she, with that red hair?

CJ: But it’s one of those movies, ’cause I wasn’t in it that much, I didn’t interact —

RG: Who directed that?

CJ: Was it Roy Rowland, maybe?

RG: That sounds right. I wouldn’t swear to it. But you had a bigger part in Rio Grande (1950).

RG: That sounds right. I wouldn’t swear to it. But you had a bigger part in Rio Grande (1950).

CJ: Oh, I had a big part in Rio Grande.

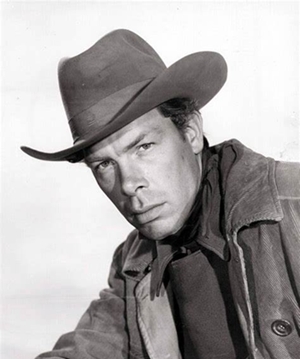

RG: And working with John Ford. What was that like? Was that like a master class in acting?

CJ: Just great. Working with all those people. You get into that — It’s like a — He had his own group of people who made up, who were always in his movies. Victor McLaglen, Ward Bond, Harry Carey Jr., Ben Johnson. My two favorite people were Ben Johnson and “Dobie” Carey. It’s interesting because Ford always had somebody that would be his Chosen One, that he liked, and then he’d always single out somebody that he made his Whipping Boy. It’s not that he didn’t like them. And everybody knew he was gonna do that. So they would talk about it, who’s gonna be under the gun now? And in Rio Grande it was Ben Johnson. Ben couldn’t, he couldn’t do anything right. “God, Ben, get on the damn horse and just get out of here! Just forget the lines, you’re so stupid.” He’d say all these horrible things. And then, because I — he had me come into his office three weeks before we started, said, “I want you to learn how to Roman ride.”  I said, “What’s that?” He said, “Standing on two horses and going around a ring.” I said, “Okay,” and I learned to do it. And because I was able to do that, I was, he’d always say, “This kid can do it. What are you doing?” So they would always give me a little, Dobie and Ben Johnson’d say, [elbow to the ribs gesture] “You jerk, what’re you doin’?!” Anyway, it was fun, it was a great spree that we had there, it was just a lot of fun.

I said, “What’s that?” He said, “Standing on two horses and going around a ring.” I said, “Okay,” and I learned to do it. And because I was able to do that, I was, he’d always say, “This kid can do it. What are you doing?” So they would always give me a little, Dobie and Ben Johnson’d say, [elbow to the ribs gesture] “You jerk, what’re you doin’?!” Anyway, it was fun, it was a great spree that we had there, it was just a lot of fun.

RG: So that was an enjoyable shoot?

CJ: Oh, God, yeah.

RG: Did that movie do well?

CJ: Yeah. It was the third of that…series…

JL: The Cavalry Series.

CJ: The Cavalry Series, which was Fort Apache [’48], She Wore a Yellow Ribbon [’49] and Rio Grande.

JL: That was at Republic?

CJ: That was at Republic.

RG: So were you loaned out by Metro?

CJ: No, I was gone. I was gone.

RG: How did that come about? Was it time to renew your contract and they said no? How did that come about, being released by MGM?

CJ: Five years.

RG: You had a five-year contract?

CJ: I had a seven-year contract, but they let it go after five years.

RG: So they just paid you off for the remaining two years?

CJ: Yeah. But see, that was a time when the studio, when TV was coming on, that’s when Hollywood was undergoing radical, radical changes.

JL: A lot of belt-tightening.

CJ: Oh my God, everyone, they were buying everybody out. ‘Cause the guys in New York were running the show. So it was not a happy time.

JL: Was it much of a shock to go from working at MGM to working at Republic?

CJ: Well, the only thing I did at Republic was Rio Grande, and with John Ford you’re working for John Ford, you’re not working for Republic.

JL: But then there was Fair Wind to Java [1953].

JL: But then there was Fair Wind to Java [1953].

CJ: Fair Wind to Java, this was — [Studio boss Herbert J.] Yates was married to Very Ralston, and this was where he’s spending the money because he wanted to make Vera Ralston a big star.

RG: Didn’t happen.

CJ: [Laughing] It was so funny. They had these love scenes, and Fred MacMurray was so — He’d say to me, “God, I don’t know why I agreed to make this movie.” She was always the dancing girl, it was just a joke, the whole movie. But he [Yates] spent the money, he had all these [actors], Victor McLaglen, he spent the money to have the cast because Yates wanted his wife to be happy.

RG: Did John Ford work with you one-on-one a lot?

CJ: Sure, absolutely.

RG: Would you read a scene for him, and he would coach you, or would it be on the set, or how did it work?

CJ: Yeah, he would do it on the set. He was definitely a hands-on director, as opposed to others that weren’t. He was a very — he knew what he wanted, and he was in charge.

JL: And you were more the Chosen One than the Whipping Boy, I take it.

CJ: Exactly.

RG: That’s interesting about the Whipping Boy. It reminds me, Darryl Hickman told me, when he was making Leave Her to Heaven with Gene Tierney. John Stahl was directing the film over at 20th Century Fox, and Darryl was the Whipping Boy. He called him “Boy”, he didn’t call him by his first name, he was just nasty to him, horrible to him. So they sent the rushes to Zanuck, and Zanuck saw the rushes and he said, “This Hickman boy is the best thing in the movie.” And from then on —

CJ: He was okay.

[Laughter.]

RG: John Stahl was just fine and dandy to Hickman.

CJ: That’s funny.

RG: But he also said making Grapes of Wrath with John Ford, he stood behind the cameras and watched Henry Fonda and Jane Darwell do those scenes, and he said it was his master class in acting, watching those two work together.

CJ: That’s one of my all-time favorite movies. Grapes of Wrath is just…

RG: And then you had a chance to work with that director, my goodness.

CJ: Yeah. It’s interesting because Ford later had kind of a falling-out with both Wayne and Henry Fonda. Ford, he would be nasty to Wayne, and Wayne would say, “Look, I’m working for half what I normally get.” Just ’cause he knows Ford would want him. “I could be making a lot more money, but I’m doing this for Ford, so why do I have to take all this abuse?” And as he got older he got — and I think Fonda just ended up hating Ford as he got older.

JL: Well, they came to blows. Ford decked him.

CJ: Did he?

JL: Yeah, it was on Mister Roberts [1955].

CJ: Well, Mister Roberts was when it all fell apart.

JL: That was when it blew up. John Ford punched him in the mouth and walked off.

CJ: He’d kind of…folded, he’d kind of gotten off the deep end at that point.

RG: John Ford?

CJ: Yeah.

RG: What was Maureen O’Hara like?

CJ: Oh, she was wonderful. Now there — she could do no wrong for Ford, he loved her. He thought she was, you know, the greatest. They went on and made The Quiet Man [1952] after Rio Grande. He loved Maureen.

JL: Actually, they did Rio Grande as a condition of making The Quiet Man. ‘Cause he thought Rio Grande was gonna make the money, Yates thought Rio Grande was gonna make all the money and Quiet Man wasn’t gonna make a dime. And they both made money.

CJ: Yeah, I think Ford always — when you have the combination of John Wayne and John Ford, it’s gonna be something worth seeing.

RG: Okay, now from MGM to Republic — maybe it’s not really Republic, but John Ford actually — how does Claude Jarman Jr. wind up at Disney?

CJ: Well, I still had one other movie I made, Hangman’s Knot [1952]. At this point I was in school in Nashville. I’d come to California to make movies. That’s when I did Inside Straight [1951], I came out, Rio Grande, I was living in Nashville. And then when I made Hangman’s Knot I came to California. It was shot in 18 days. Pretty amazing.  What I loved about it was it was the first time I got to know Lee Marvin. I thought he was the greatest. Oh God, he was so much fun. You know, he was a hero.

What I loved about it was it was the first time I got to know Lee Marvin. I thought he was the greatest. Oh God, he was so much fun. You know, he was a hero.

RG: Kind of a macho, a man’s man.

CJ: He was a hero, he was a man’s man. He was a marine, and you know he was funny, had a little Thunderbird, I’d drive around with him all the time. You know, I’m 17. He was fabulous. [NOTE: The Ford Thunderbird did not hit the market until 1955; the car in which Claude drove around with Lee Marvin in 1952 must therefore remain one of history’s unanswered questions.]

RG: What studio was that filmed?

CJ: Columbia, I think.

RG: That was Columbia. So now you’re gone from MGM, you’re basically on your own?

CJ: Yeah, the only other thing I did at MGM after I left was Inside Straight, was an MGM film. And that’s right after I’d left.

RG: Do you attribute a lot of your roles in your career as a young boy, did you have a good manager that helped you get these roles, or were you called for? Were you called up specifically by directors or casting directors for parts?

CJ: I had an agent while I was at MGM — actually, maybe I had him further than that — named Jules Goldstone. He was an attorney, and he was Clarence Brown’s attorney, and he was Elizabeth Taylor’s agent. But he wasn’t somebody out there promoting me.

RG: He’d just negotiate the deals for you?

CJ: He would negotiate the deals, yeah.

RG: And your parents, were they speaking for you on your behalf at that time until you were 18?

CJ: Yeah.

RG: Did you have nice parents that were looking out after you?

CJ: Well, my father pretty much devoted time to me while I was at MGM. And then when I moved back to Nashville and he went to work back again, and worked for the state, people came to me, I wasn’t out looking for roles.

RG: When you were in Hollywood at MGM, were you able to support your family?

CJ: Yes. Yeah. Well, my father, they put him under contract.

RG: Oh, so they gave him a salary?

CJ: Yeah.

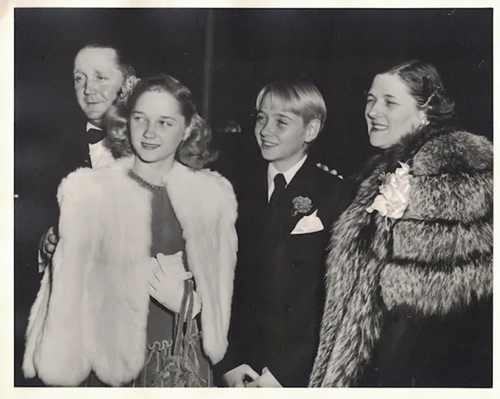

RG: Was he the one with you on the set, then, your father?

CJ: Yes.

RG: And your mother?

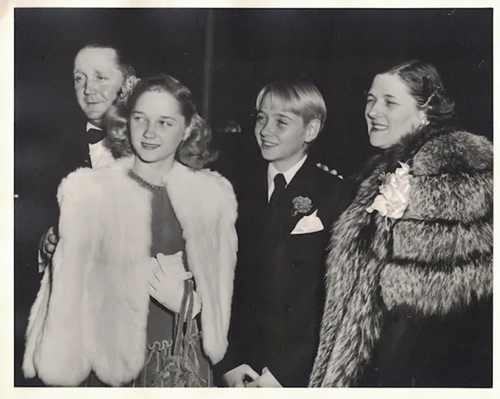

CJ: No. We were — they were in California, and my sister, who’s 18 months older than I am, was…They lived in California, came back, we were making The Yearling — When we came back from Florida in August, they stayed in California until, oh maybe three years. At that point I was working all the time, I was making a movie or getting ready to make a movie, and I was always on location. So they said, “We’ll go and move back to Nashville.” So they did.

CJ: No. We were — they were in California, and my sister, who’s 18 months older than I am, was…They lived in California, came back, we were making The Yearling — When we came back from Florida in August, they stayed in California until, oh maybe three years. At that point I was working all the time, I was making a movie or getting ready to make a movie, and I was always on location. So they said, “We’ll go and move back to Nashville.” So they did.

RG: So you have a sister?

CJ: I have a sister.

RG: Just two children, you and your sister?

CJ: Yeah. She lives in Atlanta.

RG: I see. Where was she during your…?

CJ: She went to the public school, I think she went to school in Westwood.

RG: So she was in California too?

CJ: Yeah, yeah.

RG: Was there a sibling rivalry because you were famous?

CJ: Never, never. It’s amazing.

RG: Never an issue.

CJ: Never. I’ve often thought of that. We’ve always gotten along.

RG: That’s very lucky, really wonderful.

CJ: She never resented anything I did.

RG: That’s very fortunate.

CJ: Isn’t it though?

RG: Because most people aren’t like that.

CJ: I know. We just saw her a few months ago, I believe. [NOTE: Claude’s sister Mildred passed away in 2020.]

RG: What was it like at the height of your career? I mean, you were a big star at that time in the mid-to-late ’40s. What was it like to walk into a room as a kid and have people turn their heads, look at you and say, “That’s Claude Jarman.” How did that make you feel?

CJ: I guess you learn to live with it. I would hate it today with the way social media is, and those magazines. I would hate people following me around.

RG: Just poking into your private life like that?

CJ: Yeah, yeah. It wasn’t that bad in those days, you know. When you were at MGM you were handled. I had my own PR person, I had my own makeup person, I had my own tutor. For the women, the stars, the women of them, they loved it, yes, Janet Leigh and these people. “What were the best days you were making movies?” They’d say, “MGM.” I bet if you asked Elizabeth Taylor she would’ve said the same, ’cause you were nurtured.

RG: Unlike you, Elizabeth Taylor had a very dysfunctional childhood, she didn’t have the nicest parents. She really — It sounds like you kind of had a childhood at one point or another.

CJ: Yeah, I did.

RG: You were not robbed of your childhood?

CJ: No. I mean, it was different, it was definitely different, I mean I didn’t — I couldn’t just — I mean I was going to a private school, I had tutors, so it wasn’t like I was going to Beverly Hills High School or something. It was a different world.

RG: Did you date Elizabeth Taylor or any of those people?

CJ: No, I was — when I was in the eighth grade she was graduating, so she was older.

RG: The schoolhouse now on the lot is an office of an independent film production company now, it’s not even recognizable. Have you been on the lot, the Sony lot? [NOTE: The former MGM studio in Culver City now belongs to the Sony Group Corp., which owns Columbia Pictures among its many holdings.]

CJ: Not in a long time. Maybe ten years ago, I don’t know. Been a long time.

RG: What would L.B. think when he sees “Columbia Pictures” on the Thalberg Building? Can you just imagine? It says “Columbia Pictures” on the Irving Thalberg Building. The Warner Bros. logo opens Singin’ in the Rain.

CJ: It’s kinda sad, isn’t it? Huh?

RG: It’s strange, isn’t it strange?

CJ: I mean MGM is, what is that? I think of the casino in Las Vegas, I don’t even think of —

JL: There’s a book out about the MGM backlot, which is a really excellent book.

RG: Oh yeah, I have that.

JL: It must have felt at the time like all this was as permanent as the pyramids.

CJ: Oh, absolutely. Even in 1949 — maybe ’48, ’49 — you could not envision that in two years that whole system was gonna collapse. It collapsed.

JL: There are these various documentaries that show Ann Rutherford, Mickey Rooney, walking around the backlot at MGM, and you can see it on their faces, they just look kind of stunned, like they’re still thinking, “Jeez, what happened?” At the time it must’ve looked like this was going to be till the end of time.

CJ: You couldn’t see it coming. Until it happened. Once it started going down it went so quickly.

RG: That was when L.B. was fired by Loew’s Inc., which just crushed him. And then Dore Schary doesn’t know anything really about running a studio, correct? I think that’s pretty much common knowledge.

CJ: The people in New York were running the show.

RG: Then just tons of movies pouring out in the ’50s with Joe Pasternak, the producer, like Richard Thorpe — they worked together, as a matter of fact — they produced these movies that were on time, they ran on budget, they came out, these cookie-cutter kinds of things. A Date with Judy, Athena, these musicals in the mid-’50s that were coming out at MGM. They even quit shooting in Technicolor because it was so expensive.

CJ: Instead of Spencer Tracy you got James Whitmore.

RG: When your contract was not renewed at Metro, was your ego wounded or did you understand what was going on? Were you bitter? How did you feel?

CJ: I was so excited! I wanted to move back to Nashville.

RG: Oh, so you were burned out on the movie business?

CJ: Yeah, I was ready to go.

RG: Really?

CJ: Yeah. ‘Cause when you look at it, I made 11 films, but I made — well, The Yearling, as I say, that was two years of my life. So that’s two of the five. And then I made High Barbaree before The Yearling even came out. They wanted to release High Barbaree before The Yearling and Clarence Brown said, “No way! You gotta do The Yearling and then you do that.” And then I continued to work, I mean I was working nonstop pretty much for the next three years. So I was kind of burned out, I was ready to take a break.

RG: You were exhausted.

CJ: Yeah.

RG: So you were happy to go back to Nashville.

CJ: I was, I was very happy to go back to Nashville. I also liked the fact that I was able to come back and make these films, and then go back. So I wasn’t sitting around waiting for my next role.

RG: When did you go into the Navy?

CJ: After I graduated from college.

RG: So that was after your movie career had ended.

CJ: Yeah. Although, wait a minute. My senior year in college — I went to Vanderbilt — I got a call from a director named [Francis D.] “Pete” Lyon, said, “I’m making this movie for Disney called The Great Locomotive Chase. We’re doing it down in Clayton, Georgia” — where they made Deliverance, by the way — and he said, “Would you like to have a role in it? It’s not a big role, but I’ve got your buddy Harry Carey Jr., you know we’ve got Fess Parker, would you like to do it?” I was a senior in college, we were on the quarter system, and I looked at it and I thought, “If I drop out of school for this quarter I still could come back and graduate; I’d have to double up a little bit in the next.” I said, “Sure, let’s do it.” So I went down and spent a month in Clayton. It was really Deliverance country, it was something, boy, something else.

CJ: Yeah. Although, wait a minute. My senior year in college — I went to Vanderbilt — I got a call from a director named [Francis D.] “Pete” Lyon, said, “I’m making this movie for Disney called The Great Locomotive Chase. We’re doing it down in Clayton, Georgia” — where they made Deliverance, by the way — and he said, “Would you like to have a role in it? It’s not a big role, but I’ve got your buddy Harry Carey Jr., you know we’ve got Fess Parker, would you like to do it?” I was a senior in college, we were on the quarter system, and I looked at it and I thought, “If I drop out of school for this quarter I still could come back and graduate; I’d have to double up a little bit in the next.” I said, “Sure, let’s do it.” So I went down and spent a month in Clayton. It was really Deliverance country, it was something, boy, something else.

RG: Did you meet Disney?

CJ: Yes, he came down.

JL: He was such a railroad enthusiast, I know he loved having that movie made. Did he spend much time on the set?

CJ: No, he just came down maybe for a few days, he didn’t stay around.

RG: You got that part because the director called you up and offered it to you?

CJ: Yeah. I’d met him a couple of times times, and we’d chatted. It wasn’t like it was a huge role, but it was…

RG: Did you go back to Burbank at all for any part of the movie?

CJ: Yeah, we went back and worked. It was about three months. It was all the fall quarter, September to the end of November. Oh! Dick Sargent, you know Dick Sargent?

RG: Of course. Bewitched, is that correct?

CJ: Yeah. He was my roommate. We were all living in this motel down in Clayton.

RG: Deliverance-land. How far is Clayton from Atlanta?

CJ: A thousand miles.

[Laughter.]

RG: In 1956 how old were you?

CJ: I was 21.

RG: So you did that probably without your parents, right?

CJ: Oh yeah.

RG: Just on your own. What was your major at Vanderbilt?

CJ: I was in pre-law, but I didn’t go to law school. Back in ’56 you still could be drafted.

RG: Korea? It was after Korea, wasn’t it?

CJ: Yes, it was right after Korea. But you either had to go into the service for two years or go through the OCS [Officers Candidate School] program and officer training and spend three years, which is what I did.

RG: And then when you came out what did you do?

CJ: Well, when I came out I’d already gotten married and had a child on the way. Two years I was in Seattle, and one year — you remember the movie Don’t Go Near the Water?

JL: Oh yeah.

CJ: Glenn Ford? About PR work with the Navy where you…

JL: You don’t go near the water.

CJ: You don’t go near the water. And that’s what I did for a year, I was Armed Forces Information Office. If you were making a movie and you needed a cruiser or a destroyer, you’d call us and we’d arrange it for you. So that was what I did for a year.

RG: And after that?

CJ: After that I moved with my wife back to Birmingham and spent two years, and then got recruited to move to San Francisco to work for an insurance company [NOTE: The John Hancock Insurance Co.].

RG: So that’s how you found your way out here to the West Coast?

CJ: I got here in 1961, which is just when everything was just breaking loose out here. And then for years I was involved in the Film Festival in San Francisco.

RG: The San Francisco Arts Commission? Or what were you, the…?

CJ: Well, I was just on the board for a while, there was Shirley Temple, myself, and some other people, and it was underwritten by the Chamber of Commerce. And then I was asked to take it over and run it, which I started in ’68 and I was the director until 1980. Which was great fun ’cause I got to bringing back all the people that I knew or I wanted to know.

RG: During that time, even now, do you miss show business?

CJ: No, I don’t. I wouldn’t want to…I don’t want to sell myself out.

RG: Put up with politics…

CJ: You gotta really want it to stay in it, particular these days.

RG: Such a difficult business, isn’t it? Ugly too. It’s dog-eat-dog.

CJ: One of my daughters still wants to do that, and she’s 22. [NOTE: Claude refers here to Sarah, one of twins — the other being Charlotte — with his third wife Katharine. Claude had five other children from two previous marriages.]

CJ: One of my daughters still wants to do that, and she’s 22. [NOTE: Claude refers here to Sarah, one of twins — the other being Charlotte — with his third wife Katharine. Claude had five other children from two previous marriages.]

RG: She wants to be an actress?

CJ: Yeah, and she goes down for auditions. She’ll drive down to — she graduated from Santa Barbara — and so she drove down last week for an audition. She left — she’s working, and so she left at 2:00 in the afternoon, drove to L.A. and the audition, drove back the next day. I said, “You want to do it, move down there, ’cause you’re not gonna be able to — “

RG: Are your daughters — your twins, correct?

CJ: Yeah.

RG: Are they, do they know your films, and proud of your legacy?

CJ: Yeah, I think so. Yeah

RG: That’s very nice.

CJ: It’s still a little distant for them, you know. I mean nowadays they’re –– kids are so different now.

JL: If we could go back to the Film Festival, could you speak a little about Albert Johnson? Personally, that was when I was going to the Festival, periodically, not very often. I was down there for some of the retrospectives on Howard Hawks, Frank Capra and so forth. Could you just talk about him? I really admired him, I liked what he was trying to do with the Festival. [NOTE: Albert Johnson (1925-98) was program director of the San Francisco International Film Festival during its formative years when Claude served as festival director, and the two sparred often over finances and other issues.]

JL: If we could go back to the Film Festival, could you speak a little about Albert Johnson? Personally, that was when I was going to the Festival, periodically, not very often. I was down there for some of the retrospectives on Howard Hawks, Frank Capra and so forth. Could you just talk about him? I really admired him, I liked what he was trying to do with the Festival. [NOTE: Albert Johnson (1925-98) was program director of the San Francisco International Film Festival during its formative years when Claude served as festival director, and the two sparred often over finances and other issues.]

CJ: He was a very unique guy, very difficult in many ways ’cause he knew what he wanted to do. Albert had no vision of money, that it cost money to do things. He just thought, “Well, I’m gonna — ” And then he had no vision of time restraints. Like when we had that tribute to Bette Davis, he started films at 9:00 in the morning, Bette Davis didn’t come on until 4:00 in the afternoon.

RG: So we’re talking about the International Film Festival. From then on you’ve made, basically, the Bay Area your home?

CJ: Yes, I’ve never left.

RG: And you love it here?

CJ: Yeah, I love it here. Been here 20 years, beautiful.

RG: What was it like for you to go back to the Academy Awards when they reassembled all the —

RG: What was it like for you to go back to the Academy Awards when they reassembled all the —

CJ: Oh, it was wonderful. I wish they’d do it again.

RG: You stood on the stage with everybody, right? It was…

CJ: They did it twice. The way they did it was great. They opened the curtain and they rolled everybody out on, like, bleachers. Do you remember seeing this?

RG, JL: Yes, oh yeah, yeah.

CJ: And it was all alphabetical.

JL: In fact I remember seeing you.

CJ: And what was really great was, you’re sitting there, you’re looking [gesturing vaguely out to “the house”], and you see all these people. There’s Harrison Ford…people who were not up here. Like, I’m up here and they’re down there. And that’s kind of like…It’s kind of neat, you know? But, well, you would see all these people, people just going crazy, clapping. It was great.

RG: And did you enjoy participating in the Turner Classic Movies Film Festival?

CJ: Yeah, that was a lot of fun.

RG: What’s it like in the moment now…Like you said they screened Intruder in the Dust in Palm Springs, correct?

CJ: Right.

RG: Did you stay in the audience to watch it?

CJ: Yeah.

RG: Tell us what that felt like and what you were thinking as you were watching that film from all those years ago, looking at yourself when you were a teenager. What was going through your mind?

CJ: Well, I guess what was going through my mind — two films, I’ve done a couple of things, I did some with Rio Grande too, down in Los Angeles, the film critics had a showing down there. In both those films, I didn’t recall that I had as big a role as I did. I mean, Rio Grande, I’m in that a lot. The whole feature is the relationship that the father and the mother, John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara, have fighting over the kid. So it was interesting to see that.  Intruder in the Dust, what really inspired me was that I really thought that was a good film. I thought Clarence Brown just did a great job on that. He’d go into these scenes — I always remember that one scene with Juano Hernández in jail and I’m on the outside, we have our hands, we’re talking about what can we do —

Intruder in the Dust, what really inspired me was that I really thought that was a good film. I thought Clarence Brown just did a great job on that. He’d go into these scenes — I always remember that one scene with Juano Hernández in jail and I’m on the outside, we have our hands, we’re talking about what can we do —

JL: And you just see the eyes…

CJ: See his eyes, yeah. I mean, it was…

RG: Very powerful.

JL: Do you kinda wish Clarence Brown had lived to see that? ‘Cause it seems to me he passed away without getting the recognition he really deserved for some of the movies he made.

CJ: Well, he never did, and you know, he lived to be 90-something. He was down in Palm Springs, I used to go down and visit with him. But he made a lot of great films, he really did.

RG: He was a southerner as well, wasn’t he?

CJ: No. He went to the University of Tennessee, but he was from Boston or something, Massachusetts.

RG: Did you feel nostalgic, did you feel proud when you watched the film, or…?

CJ: Yeah, I was proud, ’cause I thought it was…I was proud to be a part of that. I thought it was an important film, it really was. And I really feel gratified that it’s finally getting the recognition that I think it’s deserved.

RG: When you watch yourself at this time also, can you look at yourself on the screen and be proud of your acting, and not criticize it necessarily, or, “I could have done this better.” Do you have any of those kinds of feelings?

CJ: Oh yeah. I can see certain scenes in Intruder that I didn’t like, that I did not like the way that I had played it. I could watch The Yearling and I could tell you — I could see scenes that I was in when I first started filming, and I could see scenes eight months later.

RG: You saw yourself getting better.

CJ: Yeah, that was better.

RG: You never had any acting lessons?

CJ: No.

JL: Pauline Kael was a great admirer of Clarence Brown’s, and she said — and I think she’s right — she said that he got Elizabeth Taylor’s best performance ever out of her in —

CJ: National Velvet.

JL: I think the same is true of you in The Yearling, especially for being such a newcomer.

CJ: Yeah, he was…There was something that was very intimate about Clarence. He was able to say, “Trust me, look at me,” and you kind of forget everything that’s going on around you.

RG: Was he quiet?

CJ: Quiet, he was quiet. He always kinda wore a coat and tie.

RG: So he was formal. He was of the old school.

CJ: Yeah.

RG: Not like Arthur Freed.

CJ: [Laughing.] No!

RG: Miserable, nasty, loudmouthed. Arthur Freed had no class. But he could recognize talent, he assembled the best talent in the world, a man that had no class or really any education.

JL: He exposed himself to Shirley Temple when she was 15.

[Claude laughs.]

RG: Did you know Gertrude Temple, the mother?

CJ: No.

RG: She’d say to Shirley, “Sparkle and shine, Shirley! Sparkle and shine!” That’s what she’d — ‘Cause Gertrude would not let…Jane Withers couldn’t play with her, nobody, the children on the lot, you did not play with Shirley Temple. She was kept away from the other children, Gertrude kept her away. She’d just say, “Sparkle and shine, Shirley!” You know who told me that? Baby Peggy. You remember — do you know Baby Peggy?

CJ: I know who she is, yeah.

JL: Diana Serra Carey.

CJ: I see Shirley’s son, Charlie Black.

CJ: I see Shirley’s son, Charlie Black.

RG: Oh I know. He’s a Bohemian, Charlie Black. [NOTE: That is, a member of the Bohemian Club, a private gentlemen’s club, based in San Francisco, that hosts events at the Bohemian Grove campground in Monte Rio, Sonoma County, Calif.]

CJ: I’d see him up at the Grove.

RG: Yes, I know Charlie.

CJ: I’d ask him, I’d say, “How’s your mom?” He’d say, “Well, she was…” I guess they made her have someone live in the house with her after her husband died [in 2005]. But she would lock herself in her bedroom and wouldn’t let the woman come in who was there, supposed to be taking care of her. And then she fell.

RG: The beginning of the end.

CJ: Yeah. So he was…

[Resuming later; Claude sits holding the full-size Oscar that replaced the miniature one he received in 1947.]

RG: Okay. So can you give us some memories? Do you remember receiving the award? Could you hold it up a little?

RG: Okay. So can you give us some memories? Do you remember receiving the award? Could you hold it up a little?

CJ: Sure.

RG: There it is, that’s perfect. Do you remember the night you got it?

CJ: I remember the night I got it, it was at the Shrine Auditorium, I think, downtown Los Angeles. I was told that I might be getting one.

RG: Oh so you didn’t know?

CJ: I didn’t know, but I was told I might be, so I was prepared to say something. It’s funny, my wife, when I had my 75th birthday, she did a film of my life. And she had gotten my acceptance talk that I did on radio. It was pretty amazing.

RG: So the audio exists?

CJ: The audio exists. I don’t know how she found it but she got it, and it was in the film.

RG: Who presented it to you?

CJ: Shirley Temple.

RG: Shirley Temple. So you’re in the audience for the Academy Awards, and it’s 1947, and you’re sitting there as a star or whatever, and they say, “We’d like to call Claude Jarman Jr. up to the stage to receive and honorary Oscar…”

CJ: Well, she comes out, Shirley comes out and says, “We want to make a special presentation to the outstanding child actor of 1946.” And, “Claude Jarman Jr.” And then I get up…

RG: And how did you feel when you were honored like that?

CJ: You know what, it didn’t register that much for me, y’know. It was…has more significance today than it did then, let’s put it that way.

RG: Well, your parents must’ve been proud.

CJ: Oh sure, yeah, proud. I got a lot of telegrams from the governor of Tennessee and all these people.

RG: Do you still have all that stuff?

CJ: Yeah. [Chuckles] Somewhere out there.

RG: Very exciting. I just want to thank you again for opening your house up to us.

JL: Yes!

RG: And for your kindness, appreciate it so much. We have some footage here that will — You know, I’m archiving all this stuff and making a library…

CJ: Sure.

RG: …and when I make my documentaries we’ll include bits and pieces of things…

CJ: Oh, what a great idea.

RG: …and I just thank you for — We talked about this on the camp deck [at Bohemian Grove] —

CJ: Right.

RG: — if you remember, we had some nice conversations. I think I’m going to try to get up to the Grove again this summer, so I’ll see you up there.

CJ: Please do!

* * *

And there you have it, Richard’s and my afternoon with this gracious and hospitable gentleman; may his kind soul rest in peace. I know this is a long post, but I couldn’t find a comfortable spot to break it, and it seemed better to present it as a whole rather than arbitrarily shoe-horning a “To Be Continued” in for no good reason.

And another note about that long illustration above of the gathering of past and (then) present Oscar winners. That’s from the 2003 ceremony (awards for 2002), when best picture went to Chicago and acting awards to Adrien Brody (standing left) and, standing right, Chris Cooper, Nicole Kidman, Catherine Zeta-Jones and honorary award recipient Peter O’Toole. Depending on the size and resolution of your screen, you may have trouble finding Claude; he’s seated in the second row from the top, seven in from the right, between Anjelica Huston and Jennifer Jones. As Claude says, except for that year’s winners, the arrangement is alphabetical; how many others can you identify?

On March 3, 2017, Claude Jarman Jr. welcomed my friend

On March 3, 2017, Claude Jarman Jr. welcomed my friend  JIM LANE (JL): When he showed up in your classroom did you know what he was there for?

JIM LANE (JL): When he showed up in your classroom did you know what he was there for? CJ: Well there was one named Jacqueline White who got the role. People don’t even know this, but Jackie White was the mother, she went to Florida, where we worked for three months. And when we got back to Hollywood they thought that she was really too young, she was only in her twenties, and they thought she just didn’t look mature enough to play the mother, so they replaced her with Jane Wyman. Which also meant that we had to go back and do some retakes using her instead of Jackie. [

CJ: Well there was one named Jacqueline White who got the role. People don’t even know this, but Jackie White was the mother, she went to Florida, where we worked for three months. And when we got back to Hollywood they thought that she was really too young, she was only in her twenties, and they thought she just didn’t look mature enough to play the mother, so they replaced her with Jane Wyman. Which also meant that we had to go back and do some retakes using her instead of Jackie. [ RG: Talk about your relationship with Clarence Brown, what that was like.

RG: Talk about your relationship with Clarence Brown, what that was like. CJ: Lassie bit me in the face, so I got mad.

CJ: Lassie bit me in the face, so I got mad. RG: Who was in your class?

RG: Who was in your class? CJ: Well, I know that Clarence was familiar with this and he really wanted to make this film. He never said this, but I’d read that he had been in Atlanta when there was some sort of a hanging or something, something that went on that upset him, and he always wanted to make that film. And he went to L.B. Mayer and L.B. Mayer said no. He said, “We’re doing all these musicals, we do all this wonderful stuff, why do we want to get involved in a film that deals with a lynching? And particularly with a black person, we’re just not ready for that.” And Clarence prevailed, he said, “I really want to do this.” And at that time Dore Schary was also at the studio, and Schary really wanted to do it also. So they said, “Okay, you can do it.” Probably, once it was finished, they didn’t know what to do with it. They really didn’t. They sort of buried it. It was getting great reviews in London, people were loving it, they thought it would be a possible nomination for an Academy Award. But in those days the studios would put forth the films that they wanted to be Academy Award projects; Fox would have one, Warner Bros. would have one, Paramount. And MGM did not want to put forth Intruder; they put forth, I think, Battleground or some war movie at that time. So the film did not make any money, and it just went away.

CJ: Well, I know that Clarence was familiar with this and he really wanted to make this film. He never said this, but I’d read that he had been in Atlanta when there was some sort of a hanging or something, something that went on that upset him, and he always wanted to make that film. And he went to L.B. Mayer and L.B. Mayer said no. He said, “We’re doing all these musicals, we do all this wonderful stuff, why do we want to get involved in a film that deals with a lynching? And particularly with a black person, we’re just not ready for that.” And Clarence prevailed, he said, “I really want to do this.” And at that time Dore Schary was also at the studio, and Schary really wanted to do it also. So they said, “Okay, you can do it.” Probably, once it was finished, they didn’t know what to do with it. They really didn’t. They sort of buried it. It was getting great reviews in London, people were loving it, they thought it would be a possible nomination for an Academy Award. But in those days the studios would put forth the films that they wanted to be Academy Award projects; Fox would have one, Warner Bros. would have one, Paramount. And MGM did not want to put forth Intruder; they put forth, I think, Battleground or some war movie at that time. So the film did not make any money, and it just went away. RG: Now what kind of person was Faulkner? Was he quiet, was he — ?

RG: Now what kind of person was Faulkner? Was he quiet, was he — ? RG: Then you went on to make The Outriders (1950). You were on loan for that, is that correct?

RG: Then you went on to make The Outriders (1950). You were on loan for that, is that correct? RG: That sounds right. I wouldn’t swear to it. But you had a bigger part in Rio Grande (1950).

RG: That sounds right. I wouldn’t swear to it. But you had a bigger part in Rio Grande (1950). I said, “What’s that?” He said, “Standing on two horses and going around a ring.” I said, “Okay,” and I learned to do it. And because I was able to do that, I was, he’d always say, “This kid can do it. What are you doing?” So they would always give me a little, Dobie and Ben Johnson’d say, [elbow to the ribs gesture] “You jerk, what’re you doin’?!” Anyway, it was fun, it was a great spree that we had there, it was just a lot of fun.

I said, “What’s that?” He said, “Standing on two horses and going around a ring.” I said, “Okay,” and I learned to do it. And because I was able to do that, I was, he’d always say, “This kid can do it. What are you doing?” So they would always give me a little, Dobie and Ben Johnson’d say, [elbow to the ribs gesture] “You jerk, what’re you doin’?!” Anyway, it was fun, it was a great spree that we had there, it was just a lot of fun. JL: But then there was Fair Wind to Java [1953].

JL: But then there was Fair Wind to Java [1953]. What I loved about it was it was the first time I got to know Lee Marvin. I thought he was the greatest. Oh God, he was so much fun. You know, he was a hero.

What I loved about it was it was the first time I got to know Lee Marvin. I thought he was the greatest. Oh God, he was so much fun. You know, he was a hero. CJ: No. We were — they were in California, and my sister, who’s 18 months older than I am, was…They lived in California, came back, we were making The Yearling — When we came back from Florida in August, they stayed in California until, oh maybe three years. At that point I was working all the time, I was making a movie or getting ready to make a movie, and I was always on location. So they said, “We’ll go and move back to Nashville.” So they did.

CJ: No. We were — they were in California, and my sister, who’s 18 months older than I am, was…They lived in California, came back, we were making The Yearling — When we came back from Florida in August, they stayed in California until, oh maybe three years. At that point I was working all the time, I was making a movie or getting ready to make a movie, and I was always on location. So they said, “We’ll go and move back to Nashville.” So they did. CJ: Yeah. Although, wait a minute. My senior year in college — I went to Vanderbilt — I got a call from a director named [Francis D.] “Pete” Lyon, said, “I’m making this movie for Disney called The Great Locomotive Chase. We’re doing it down in Clayton, Georgia” — where they made Deliverance, by the way — and he said, “Would you like to have a role in it? It’s not a big role, but I’ve got your buddy Harry Carey Jr., you know we’ve got Fess Parker, would you like to do it?” I was a senior in college, we were on the quarter system, and I looked at it and I thought, “If I drop out of school for this quarter I still could come back and graduate; I’d have to double up a little bit in the next.” I said, “Sure, let’s do it.” So I went down and spent a month in Clayton. It was really Deliverance country, it was something, boy, something else.

CJ: Yeah. Although, wait a minute. My senior year in college — I went to Vanderbilt — I got a call from a director named [Francis D.] “Pete” Lyon, said, “I’m making this movie for Disney called The Great Locomotive Chase. We’re doing it down in Clayton, Georgia” — where they made Deliverance, by the way — and he said, “Would you like to have a role in it? It’s not a big role, but I’ve got your buddy Harry Carey Jr., you know we’ve got Fess Parker, would you like to do it?” I was a senior in college, we were on the quarter system, and I looked at it and I thought, “If I drop out of school for this quarter I still could come back and graduate; I’d have to double up a little bit in the next.” I said, “Sure, let’s do it.” So I went down and spent a month in Clayton. It was really Deliverance country, it was something, boy, something else. CJ: One of my daughters still wants to do that, and she’s 22. [

CJ: One of my daughters still wants to do that, and she’s 22. [ JL: If we could go back to the Film Festival, could you speak a little about Albert Johnson? Personally, that was when I was going to the Festival, periodically, not very often. I was down there for some of the retrospectives on Howard Hawks, Frank Capra and so forth. Could you just talk about him? I really admired him, I liked what he was trying to do with the Festival. [

JL: If we could go back to the Film Festival, could you speak a little about Albert Johnson? Personally, that was when I was going to the Festival, periodically, not very often. I was down there for some of the retrospectives on Howard Hawks, Frank Capra and so forth. Could you just talk about him? I really admired him, I liked what he was trying to do with the Festival. [ RG: What was it like for you to go back to the Academy Awards when they reassembled all the —

RG: What was it like for you to go back to the Academy Awards when they reassembled all the — Intruder in the Dust, what really inspired me was that I really thought that was a good film. I thought Clarence Brown just did a great job on that. He’d go into these scenes — I always remember that one scene with Juano Hernández in jail and I’m on the outside, we have our hands, we’re talking about what can we do —

Intruder in the Dust, what really inspired me was that I really thought that was a good film. I thought Clarence Brown just did a great job on that. He’d go into these scenes — I always remember that one scene with Juano Hernández in jail and I’m on the outside, we have our hands, we’re talking about what can we do — CJ: I see Shirley’s son, Charlie Black.

CJ: I see Shirley’s son, Charlie Black. RG: Okay. So can you give us some memories? Do you remember receiving the award? Could you hold it up a little?

RG: Okay. So can you give us some memories? Do you remember receiving the award? Could you hold it up a little?

I was dismayed and saddened by the passing of Claude Jarman Jr. last week. He lived a long, happy and memorable life, and he left this world peacefully in his sleep at the age of 90. But that’s not really much of a comfort; irrational as it may be, there are always people whom you subconsciously nominate to live forever, and Claude Jarman was one of those.

I was dismayed and saddened by the passing of Claude Jarman Jr. last week. He lived a long, happy and memorable life, and he left this world peacefully in his sleep at the age of 90. But that’s not really much of a comfort; irrational as it may be, there are always people whom you subconsciously nominate to live forever, and Claude Jarman was one of those. So…Where was I? Oh Yes,

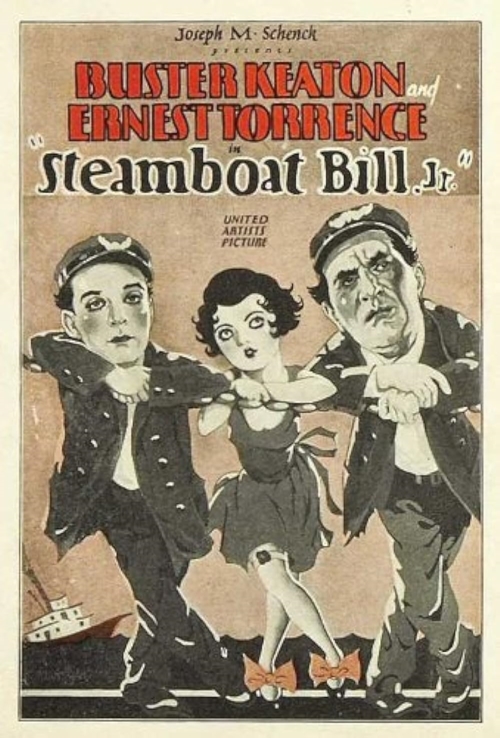

So…Where was I? Oh Yes,  I used to screen Steamboat Bill, Jr. for my Film Studies classes at a local community college here in Sacramento, not only because it’s a masterpiece, but for a local connection to which my students could relate: Keaton shot the picture on the outskirts of Sacramento, building his fictitious town of River Junction on the west bank of the Sacramento River (doubling for the Mississippi), just above its confluence with the American River. The opening shot, panning from the American to the Sacramento and the River Junction set, is instantly recognizable to local residents today — if they can imagine the wide swath of Interstate 5 bisecting the frame.

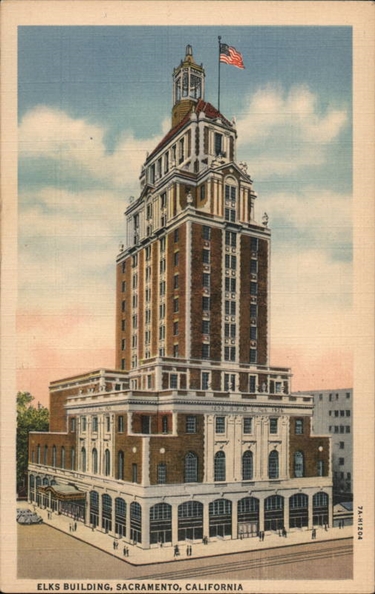

I used to screen Steamboat Bill, Jr. for my Film Studies classes at a local community college here in Sacramento, not only because it’s a masterpiece, but for a local connection to which my students could relate: Keaton shot the picture on the outskirts of Sacramento, building his fictitious town of River Junction on the west bank of the Sacramento River (doubling for the Mississippi), just above its confluence with the American River. The opening shot, panning from the American to the Sacramento and the River Junction set, is instantly recognizable to local residents today — if they can imagine the wide swath of Interstate 5 bisecting the frame. But I think a likelier candidate is this one on the left, Sacramento’s Elks Building, one block east at 11th and J. Recently completed in 1928, it was then the tallest building in Sacramento, the first one taller than the Capitol. Both the Elks and Insurance Buildings are still standing, but it’s too late to resolve the issue now; even if we could identify the exact spot where Keaton and director Charles Reisner placed their camera, too many newer, taller buildings have sprung up, on both sides of the river, in the 97 years since Buster and Marion stood there thinking wistfully of each other.