Chapter II of Glamour Boys is now published. Look under the Fiction menu, or click here to go directly without having to scroll down through Chapter I.

Again, I hope it meets with your approval…

Chapter II of Glamour Boys is now published. Look under the Fiction menu, or click here to go directly without having to scroll down through Chapter I.

Again, I hope it meets with your approval…

I’m preparing a post now on Clara Bow’s career in talking pictures, a career that was longer and more estimable than posterity has given her credit for. Well, as so often happens here at Cinedrome, that post is growing and deepening as I work on it, and has been accordingly delayed. But it has to go on a back burner for now in any case, because my friend Robert Matzen is about to publish his latest book. It’s one that belongs on the bookshelf of every Cinedrome reader — and a lot of other bookshelves besides. This new book not only goes a long way to fill a decades-old gap in our knowledge of the life and times of one of America’s most beloved movie stars, it also adds significantly to our knowledge — at least it added to mine — of the rigors and terrors of aerial warfare during World War II.

I’m preparing a post now on Clara Bow’s career in talking pictures, a career that was longer and more estimable than posterity has given her credit for. Well, as so often happens here at Cinedrome, that post is growing and deepening as I work on it, and has been accordingly delayed. But it has to go on a back burner for now in any case, because my friend Robert Matzen is about to publish his latest book. It’s one that belongs on the bookshelf of every Cinedrome reader — and a lot of other bookshelves besides. This new book not only goes a long way to fill a decades-old gap in our knowledge of the life and times of one of America’s most beloved movie stars, it also adds significantly to our knowledge — at least it added to mine — of the rigors and terrors of aerial warfare during World War II.

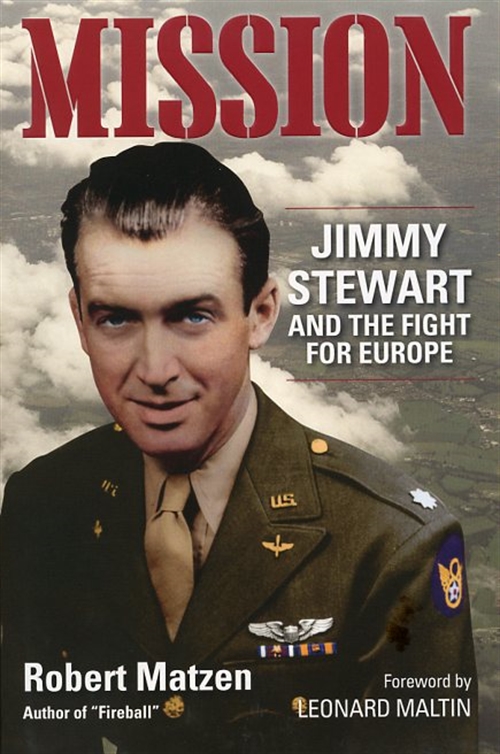

This is the book: Mission: Jimmy Stewart and the Fight for Europe. Robert Matzen, Cinedrome readers will recall, is the author of Fireball: Carole Lombard and the Tragedy of Flight 3, a riveting page-turner about the death of Carole Lombard, who became the first celebrity casualty of World War II when her plane crashed on the way home from a war bond rally in Indiana. Mission tells us, in harrowing detail, how close James Stewart — Hollywood’s “boy next door” and an Oscar winner for 1940’s The Philadelphia Story — came to becoming another casualty of that same war. And not in a stateside bond tour, but in combat in the skies over Germany.

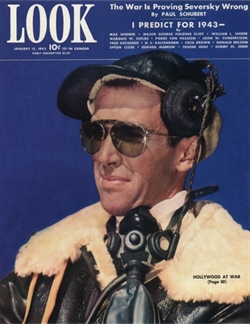

It’s common knowledge that James Stewart is one of the greatest stars in the history of Hollywood; in the American Film Institute’s 1999 list of the screen’s 50 greatest legends, he ranked third among men behind Humphrey Bogart and Cary Grant. Less commonly known is that he was the highest-ranking actor in military history (not counting Ronald Reagan’s two terms as Commander in Chief), retiring from the U.S. Air Force Reserve as a brigadier general in 1968. He always kept his screen and military careers carefully separate, especially during the war. There was a flurry of publicity when he enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps in March 1941 (nine months before Pearl Harbor), but that media circus led him to hold the press at arm’s length thereafter, and his military higher-ups generally cooperated by shielding him. Throughout the war, hopeful reporters were often reduced to filing pouty dispatches about how Lt. (later Capt., Maj., Lt. Col. and Col.) Stewart wouldn’t talk to them. And after the war, in the 52 years that remained to him, he spoke sparingly and in the most general terms about his war service. Of his experiences flying bombing missions over France and Germany — aside from a brief stint as a talking head on Thames Television’s documentary series The World at War, identified only as “James Stewart, Squadron Commander” — he spoke hardly at all.

Stewart may have virtually taken the story of his wartime service, and his 20 combat missions in B-17 and B-24 bombers, to his grave, but Robert Matzen has exhumed the bones of the story from official military records and mission reports, and fleshed them out with the diaries, memoirs and recollections of the men who flew with Stewart and others like him, and with his own understanding of aeronautics born of ten years working in communications for NASA. He also gives us a keen insight into the tradition of military service that ran back generations in Jimmy Stewart’s family, something Stewart himself never elaborated on — perhaps because it would sound too much like bragging, perhaps because it was too internalized to bring to the surface.

Stewart may have virtually taken the story of his wartime service, and his 20 combat missions in B-17 and B-24 bombers, to his grave, but Robert Matzen has exhumed the bones of the story from official military records and mission reports, and fleshed them out with the diaries, memoirs and recollections of the men who flew with Stewart and others like him, and with his own understanding of aeronautics born of ten years working in communications for NASA. He also gives us a keen insight into the tradition of military service that ran back generations in Jimmy Stewart’s family, something Stewart himself never elaborated on — perhaps because it would sound too much like bragging, perhaps because it was too internalized to bring to the surface.

Strictly speaking, Jimmy Stewart was actually James Maitland Stewart II (though his birth certificate didn’t put it that way). J.M. the First was his paternal grandfather, a Signal Corps sergeant during the Civil War who rode with Sheridan and Custer in the Shenandoah Valley in 1864, saw action at Cedar Creek, Five Forks and Sailor’s Creek, and was present at Appomattox Court House as Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant. Fifty years later, he would regale young Jim with tales of seeing Lee, Grant, Sheridan, Custer and Lincoln all in the flesh. “This,” Matzen tells us succinctly, “wasn’t history in a book.” (Did young Jim reflect on this family lore in 1938, when he played a Union Army doctor receiving an audience with President Lincoln in Of Human Hearts? How could he not?) Sgt. Stewart also had a brother Archibald who didn’t survive the war, falling at Spotsylvania.

Then there was Jim’s maternal grandfather, Col. Samuel M. Jackson, who fought in the Wheatfield at Gettysburg and helped hold the Federal left on the second day, rising to the rank of general by war’s end. Gen. Jackson died before Jim was born, but his devotion to serving his country remained legendary in the family and mingled with that of Sgt. Stewart and his brother Archie.

And with that of Jim’s own father Alexander. He served briefly in the Spanish-American War but saw no action; he fell ill in Puerto Rico, and that “splendid little war” was over before he recovered. He didn’t give up; 20 years later, age 45 and married with children, he re-enlisted when America entered the Great War and served in France in the Ordnance Repair Dept.

A future in military service for James Stewart the Younger was a foregone conclusion, and he began preparing for it even as he was climbing the ladder to stardom in Hollywood (and, as a playboy bachelor, cutting a swath through Tinsel Town’s female population, amusingly recounted by Matzen). An early fascination with aviation (and hero-worship of Charles Lindbergh, whom he would later play in the movies) made him set his sights on the Army Air Corps, plunging into flying lessons as soon as he could afford them. (Fun Little-Known Fact: James Stewart got his commercial pilot’s license even before his first Oscar nomination.)

When Mission follows Capt. Stewart to combat duty in England, after a frustrating two years stateside training men to face the action he wanted to see, the book becomes an eye-opening chronicle of the nightmare of aerial combat. Robert Matzen puts us on the flight deck and in the bomb bays and gun turrets as vividly as Laura Hillenbrand put us in the saddle in her brilliant Seabiscuit. Reading Mission is as close as you’ll ever want to get to flying at 20,000 feet swaddled in a heated suit against the 40-below weather, icicles dangling from (and occasionally clogging) your oxygen mask, struggling to keep your behemoth plane in formation while anti-aircraft flak rips holes in your fuselage and hundreds of Luftwaffe fighters swarm around you like death-dealing wasps. Twenty times Oscar-winner Stewart went through it — eight, nine, ten hours in the air, never knowing which split-second might be his last. No wonder he never talked about it.

As he did in Fireball, Matzen completes the picture he paints by recounting the experiences of others who lived through the air war over Europe from perspectives of their own. From top to bottom here:

As he did in Fireball, Matzen completes the picture he paints by recounting the experiences of others who lived through the air war over Europe from perspectives of their own. From top to bottom here:

Sgt. Clement Leone of Baltimore, a radio operator in Stewart’s combat wing, who was a senior in high school when Pearl Harbor was attacked, and whose fascination with airplanes, like Stewart’s, channeled him into the Air Corps once he turned 18. Leone’s exploits, especially after being blown out of his exploding plane over German territory, would make a book in themselves. (Non-spoiler alert: Leone survived, came home, and is today alive and well; he was a key source of Robert Matzen’s insight into life in a bomber crew.);

Gen. Adolf Galland (with the moustache) of the Luftwaffe’s fighter wing, who flew hundreds of missions against American bombers, and did not share Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring’s contempt for the Americans and their Flying Fortresses and Liberators; and

The Siepmann family of Wilhelmshaven, later Eppstein near Frankfurt. Papa Hans was a naval engineer working on U-boats. Mama Riele and their children lived through the Allied bombing campaign as civilians cowering in the shadow of those planes overhead; they didn’t share Göring’s contempt either. Their oldest child Gertrud (far left) later married an American G.I. and emigrated to America in 1956. Robert Matzen knew her for years as Trudy McVicker before learning of her childhood in Hitler’s Germany and coaxing her to contribute her memories to Mission.

Whether you’re interested in Jimmy Stewart, Hollywood, World War II, or all three, you want to read Mission. The official publication date is Monday, October 24. You can order the book here from Amazon. And you can learn more about the book here, about stops on the upcoming Mission National Book Tour here, and about Robert Matzen himself here.

Take my advice and don’t let any grass grow under your feet. I won’t be surprised if the first printing sells out.

Today marks the beginning of my first work of new fiction here at Cinedrome; the title is Glamour Boys. Now here, I guess, if I was really good at this sort of thing, I’d launch into some tantalizing inside-flap-of-the-dust-jacket copy describing the story and the characters, hooking and reeling you in like an expert fisherman. But honestly, that’s not really my long suit; I think I’d rather just let Chapter I, and those that follow, speak for themselves. To begin reading, hover on Jim’s Fiction at the top and select the title.

Glamour Boys, I say again, is a work of fiction. The persons, firms and events portrayed therein are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. No identification with any real firms, or with any real persons living or dead, is intended, and none should be inferred.

That said, I hope it meets with your approval…

Welcome to the New! Improved! Cinedrome! As you can see, there’s a new look and a lot of new features. I’ll go over some of them with you now.

First, in the right column:

And up top:

In addition to these, there’s my Links and Resources page, imported from before, and a Contact page for info on how to get in touch with me; it’s always a pleasure to hear from any and all of you.

I’m grateful to my good friend Jean Black at My Big Fat Sites for bringing all this to fruition. I hope you like the new Cinedrome; feel free to look around, make yourself comfortable, and come back often.

Coming up next – Clara Talks!

Sunday, the last day of Cinevent 2016, got off to a vivacious start with a double feature showcasing that most utterly, charmingly, irresistibly delightful of movie stars, Clara Bow. Only the persistent prejudice against silent movies keeps Clara Bow from her rightful place among the movies’ greatest stars — in the minds of the general public, that is; true movie buffs know her worth. Greta Garbo and Marilyn Monroe, at the height of their careers, were never as popular or as sexy as Clara. But Greta and Marilyn are enshrined in the Temple of Screen Immortals, even to people who know them only by name, while the name of Clara Bow is something out of a quaint, distant, forgotten prehistory, like Nell Gwyn or Minnie Maddern Fiske.

This is unfair. To see Clara Bow at her best — in Mantrap (1926), or in It or Wings (both ’27) — is to see someone who is still as animated and as immediately alluring as she was the day she reported to the set. Everybody who ever worked with Clara spoke of her ever after with a wistful smile. More to the point, the camera loved her as it has loved few other women who ever stood in front of one.

She’s been the victim, perhaps, of the legend that her atrocious Brooklyn accent doomed her when sound came in. Not so. While it’s true that the microphone terrified her at first, she rolled with the punch and gamely soldiered on. In her 11-year career she appeared in 56 features, and 11 of them were talkies. There was nothing wrong with her voice, any more than there was with Jean Harlow’s (the two women’s careers overlapped by a few years). Clara’s sound pictures did reasonably well at the box office, though it’s true, not as well as her silents. But that’s not because Clara was talking now. The simple truth is that her day was passing, while Jean Harlow’s was coming on.

I’ll save any further thoughts for another day. For now, let’s turn to Clara’s Sunday double bill in Columbus.

First came The Saturday Night Kid (1929), based on Love ‘Em and Leave ‘Em, a 1926 play by George Abbott and John V.A. Weaver. The play was filmed silent (also in ’26) under its original title (and screened at Cinevent in 2010), with Evelyn Brent and Louise Brooks playing Mame and Janie Walsh, two sisters who work together at a big department store. Mame is the older, more responsible one, forever mother-henning her hedonistic, troublemaking kid sister Janie. For this talkie remake, Clara played the slightly renamed Mayme and Jean Arthur was Janie (though she was in fact five years older than Clara). Janie is a hell-raiser and borderline sociopath, playing the ponies with the store empoyees’ charity fund, losing it, then blaming Mayme for the embezzlement — and even trying to steal Mayme’s boyfriend (James Hall). Clara wasn’t looking her best (she was, just this once, a trifle overweight and a bit frowzy), but the picture was a hit in 1929 and it still plays well; when Mayme finally got fed up and slapped Janie clear across their bedroom, applause rippled through the Cinevent audience.

First came The Saturday Night Kid (1929), based on Love ‘Em and Leave ‘Em, a 1926 play by George Abbott and John V.A. Weaver. The play was filmed silent (also in ’26) under its original title (and screened at Cinevent in 2010), with Evelyn Brent and Louise Brooks playing Mame and Janie Walsh, two sisters who work together at a big department store. Mame is the older, more responsible one, forever mother-henning her hedonistic, troublemaking kid sister Janie. For this talkie remake, Clara played the slightly renamed Mayme and Jean Arthur was Janie (though she was in fact five years older than Clara). Janie is a hell-raiser and borderline sociopath, playing the ponies with the store empoyees’ charity fund, losing it, then blaming Mayme for the embezzlement — and even trying to steal Mayme’s boyfriend (James Hall). Clara wasn’t looking her best (she was, just this once, a trifle overweight and a bit frowzy), but the picture was a hit in 1929 and it still plays well; when Mayme finally got fed up and slapped Janie clear across their bedroom, applause rippled through the Cinevent audience.

Next, Kid Boots (1926) was one of those oddities, a silent movie based (albeit loosely) on a Broadway musical comedy produced by Florenz Ziegfeld. Ziegfeld’s star Eddie Cantor made his screen debut here, playing a man hired to flirt with a rich man’s gold-digging wife and give the husband grounds for divorce. At a mountain resort, Eddie hits it off with the swimming instructor — but their romance proceeds awkwardly because every time she sees him he’s wooing somebody else. Since Eddie couldn’t resort to song-and-dance, he was teamed with Clara (as the swimming instructor) for box-office insurance. It was a felicitous pairing. The two got along famously; Eddie helped Clara with her comic timing and she helped him learn how to act for the camera, and their rapport and mutual affection still come through on the screen.

After lunch there was a new wrinkle this year. They called it the Audience Choice Picture: Earlier in the year, on the Cinevent Web site, those of us planning to attend were polled as to which of four titles we’d like to see screened in this slot. I can’t remember what the four choices were, nor which one I voted for, but we wound up with The Parson of Panamint (1941), from a story by Peter B. Kyne. Like Kyne’s perennially popular The Three Godfathers, the story was a parable. Charlie Ruggles (in a change-of-pace straight dramatic role) plays the mayor of the rough-and-tumble mining town of Panamint, California. The mayor goes to the big city of San Francisco to hire a preacher for his town’s new church, and that’s where he finds the Rev. Philip Pharo (Phillip Terry) — not in a church, but taking the mayor’s part in a saloon fight. The Rev. Mr. Pharo accepts the job and rides back with the mayor to his new congregation.

After lunch there was a new wrinkle this year. They called it the Audience Choice Picture: Earlier in the year, on the Cinevent Web site, those of us planning to attend were polled as to which of four titles we’d like to see screened in this slot. I can’t remember what the four choices were, nor which one I voted for, but we wound up with The Parson of Panamint (1941), from a story by Peter B. Kyne. Like Kyne’s perennially popular The Three Godfathers, the story was a parable. Charlie Ruggles (in a change-of-pace straight dramatic role) plays the mayor of the rough-and-tumble mining town of Panamint, California. The mayor goes to the big city of San Francisco to hire a preacher for his town’s new church, and that’s where he finds the Rev. Philip Pharo (Phillip Terry) — not in a church, but taking the mayor’s part in a saloon fight. The Rev. Mr. Pharo accepts the job and rides back with the mayor to his new congregation.