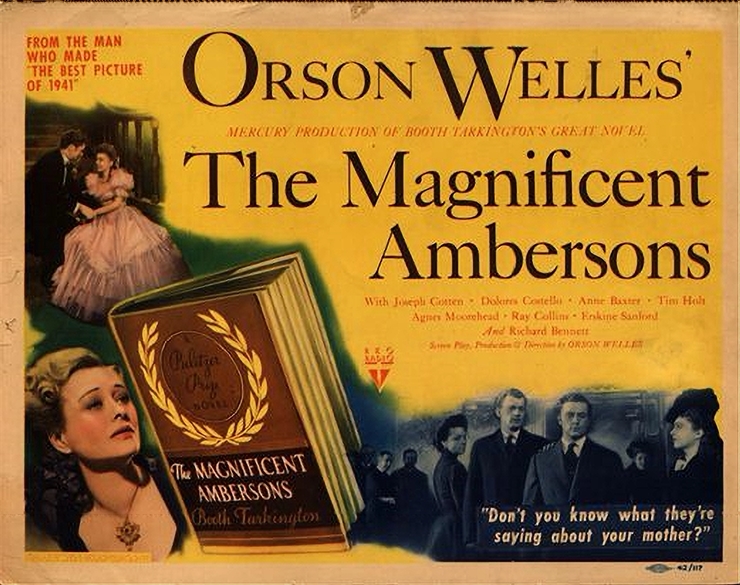

Minority Opinion: The Magnificent Ambersons, Part 6

I worked with Robert Wise once. In 1986 I played a small role in Wisdom, on which he served as executive producer and all-round good shepherd for first-time writer-director Emilio Estevez. My scene was a small one, only about 45 seconds on screen, but it meant two twelve-hour days on the set. As I reported for work on my first day, Wise came up to me and introduced himself (as if it were necessary!). There was something I had thought and said about him more than once in the past, but now, to my amazement, I actually had the chance to say it to him in person: “I have to tell you, Mr. Wise, I think you’re the greatest film editor who ever picked up a pair of scissors.”

I worked with Robert Wise once. In 1986 I played a small role in Wisdom, on which he served as executive producer and all-round good shepherd for first-time writer-director Emilio Estevez. My scene was a small one, only about 45 seconds on screen, but it meant two twelve-hour days on the set. As I reported for work on my first day, Wise came up to me and introduced himself (as if it were necessary!). There was something I had thought and said about him more than once in the past, but now, to my amazement, I actually had the chance to say it to him in person: “I have to tell you, Mr. Wise, I think you’re the greatest film editor who ever picked up a pair of scissors.” Nowadays, in hindsight, with World War II safely won and South America no longer leaning toward the U.S.’s Axis foes (beyond playing host to the occasional Nazi fugitive), we can see that flying down to Rio to make It’s All True was probably the biggest mistake Orson Welles ever made; it cut short (like a brick wall) the momentum of his rocketing career, and he never really got it rolling again. Welles no doubt came to see it that way himself, judging from the way he distanced himself from the decision. “I was sent to South America by Nelson Rockefeller and Jock Whitney,” he said. “I was told that it was my patriotic duty to go and spend a million dollars shooting the Carnival in Rio.” Sounds almost as if he was drafted, doesn’t it? Uncle Sam walked up out of the blue, poked a finger in his chest and growled “I want you!” Actually, when Whitney and Rockefeller made their proposal, Welles took little persuading; he deliberated barely 24 hours before agreeing to go.

Nowadays, in hindsight, with World War II safely won and South America no longer leaning toward the U.S.’s Axis foes (beyond playing host to the occasional Nazi fugitive), we can see that flying down to Rio to make It’s All True was probably the biggest mistake Orson Welles ever made; it cut short (like a brick wall) the momentum of his rocketing career, and he never really got it rolling again. Welles no doubt came to see it that way himself, judging from the way he distanced himself from the decision. “I was sent to South America by Nelson Rockefeller and Jock Whitney,” he said. “I was told that it was my patriotic duty to go and spend a million dollars shooting the Carnival in Rio.” Sounds almost as if he was drafted, doesn’t it? Uncle Sam walked up out of the blue, poked a finger in his chest and growled “I want you!” Actually, when Whitney and Rockefeller made their proposal, Welles took little persuading; he deliberated barely 24 hours before agreeing to go. Orson Welles was, let’s admit it, a man of prodigious, even titanic gifts — the kind of artist who comes along not once in a lifetime, or once in a century, but once in history. Three major media of the first half of the 20th century — radio, the stage and motion pictures — had never seen anything like him. He was a unique phenomenon, like Joan of Arc (meaning no other comparisons, of course). But he wasn’t omniscient, omnipotent or infallible. If I seem to be hard on him in these posts, it’s because I think he blundered badly on both It’s All True and The Magnificent Ambersons, and because I think that in his public remarks about Robert Wise he was often shabby and small; Wise — at least in his conversations with me — showed far more sympathy for Welles’s situation than Welles ever showed for his. (Welles, for his part, called Wise an idiot.) The fact is, Welles walked into his situation with his eyes wide open; Wise’s situation was thrust upon him willy-nilly by Orson Welles.

Orson Welles was, let’s admit it, a man of prodigious, even titanic gifts — the kind of artist who comes along not once in a lifetime, or once in a century, but once in history. Three major media of the first half of the 20th century — radio, the stage and motion pictures — had never seen anything like him. He was a unique phenomenon, like Joan of Arc (meaning no other comparisons, of course). But he wasn’t omniscient, omnipotent or infallible. If I seem to be hard on him in these posts, it’s because I think he blundered badly on both It’s All True and The Magnificent Ambersons, and because I think that in his public remarks about Robert Wise he was often shabby and small; Wise — at least in his conversations with me — showed far more sympathy for Welles’s situation than Welles ever showed for his. (Welles, for his part, called Wise an idiot.) The fact is, Welles walked into his situation with his eyes wide open; Wise’s situation was thrust upon him willy-nilly by Orson Welles.In 1984, complaining to Barbara Leaming about Joseph Cotten’s “Judas” letter, Welles said Cotten had become “an active collaborator with Wise, and the janitor of RKO, and whoever else was busy screwing it up.” This is frankly disgraceful. For the record, the men who were wrestling with The Magnificent Ambersons — while Welles was in Rio lecturing cultural groups, hatching grandiose plans for It’s All True, tossing furniture out his apartment window, and screwing chorus girls — wrestling with Ambersons were Robert Wise, whose authority was not to be questioned (until Welles chose to question it); Jack Moss, who had Welles’s full confidence (until he didn’t); and Joseph Cotten, who was probably Welles’s best friend (until, in Welles’s eyes, he wasn’t).

In This Is Orson Welles Peter Bogdanovich expands on that “janitor at RKO” crack. He asserts that RKO “approached several directors — among them William Wyler” — to recut Ambersons, but all refused out of respect for Welles. (Prof. Carringer’s history of the editing makes no mention of this.) Bogdanovich also says that producer Bryan Foy of Warner Bros.’ B-picture unit was called in. Foy’s verdict: “Too fuckin’ long. Ya gotta take out forty minutes.” Asked what to cut, he said to “just throw all the footage up in the air and grab everything but forty minutes — it don’t matter what the fuck you cut. Just lose forty minutes.” Bogdanovich cites Jack Moss as the source of this story, but I’ve been unable to find it corroborated anywhere else. I tend to suspect that the real source was Welles himself, as in “Jack Moss told me…” (If I’m mistaken about this, I’ll be happy to post an update when I know better.)

Easier to corroborate is David O. Selznick’s reaction to the editing of Ambersons. Selznick biographer David Thomson says Selznick, an admirer of Welles who had loaned the services of Stanley Cortez to photograph the picture, tried to have “the original version” deposited at the Museum of Modern Art. A worthy suggestion, Mr. Selznick, but just what is the original version? The 132-minute answer print that Wise prepared after Miami and shipped to Welles in Rio? The 110-minute version prepared at Welles’s instruction and previewed in Pomona? It couldn’t be the 148-minute version Welles mentioned to Bogdanovich because Ambersons never existed at that length.

This brings us to the central fallacy in the Magnificent Ambersons legend: the idea that Welles created a masterpiece that was slashed and mangled afterwards to what we have now. In fact, there really was no “original version” of Ambersons because Welles never finished the picture. He left for Brazil while Ambersons was in its final stages — before music and visual effects had been added, transitions (fades, dissolves, etc.) put in place, even before the order of scenes had been settled. Then, from Rio, before even seeing the 132-minute version, Welles ordered extensive changes: making the “big cut” (everything from Eugene’s letter to Isabel’s death) and removing the “Indian legend” scene and George’s auto accident; this trimmed a total of 22 minutes. If anything, that should be considered Welles’s “original version”, even though he never actually saw it, since it was ordered by him before the first preview (and before any studio panic had set in). When Orson Welles went to Rio, The Magnificent Ambersons was an unfinished work. Welles’s partisans cry that Ambersons was taken out of his hands, and they’re right. What they will never say is that he abandoned it — but in effect (if not in intention) that’s exactly what happened.

In “Oedipus in Indianapolis” Robert L. Carringer theorizes that leaving for Rio with Ambersons incomplete was Welles’s way of distancing himself from it, a process that began with his choosing not to play George Minafer himself. This distancing, Prof. Carringer thinks, rose out of Welles’s unresolved feelings about his parents — his imperious mother and feckless father — and his discomfort with the Oedipal subtext in Tarkington’s novel. Prof. Carringer’s theory is forcefully argued, but I don’t find it entirely persuasive; if that’s how Welles felt about it, why would he have filmed Ambersons at all, or done it on the radio (when he did play George) in the first place?

I think it may have been something simpler: that Orson Welles, for all his mastery of moviemaking so manifest in Citizen Kane, didn’t fully grasp the nuances of the editing process — not as early as 1942, anyhow. Certainly his first edits from Rio must have looked capricious and arbitrary, so much so that Wise and Moss immediately reversed them after they played so badly in Pomona. Then when Welles doubled down on the “big cut”, wanted to eliminate the end of the Amberson ball and the iris-out in the snow scene, and capped it all with a bizarre idea for a cheery curtain call “to leave audience happy”, how could it not look as if Welles had lost his train of thought on Ambersons, or simply didn’t understand how these changes would play?

I think it may have been something simpler: that Orson Welles, for all his mastery of moviemaking so manifest in Citizen Kane, didn’t fully grasp the nuances of the editing process — not as early as 1942, anyhow. Certainly his first edits from Rio must have looked capricious and arbitrary, so much so that Wise and Moss immediately reversed them after they played so badly in Pomona. Then when Welles doubled down on the “big cut”, wanted to eliminate the end of the Amberson ball and the iris-out in the snow scene, and capped it all with a bizarre idea for a cheery curtain call “to leave audience happy”, how could it not look as if Welles had lost his train of thought on Ambersons, or simply didn’t understand how these changes would play?Simon Callow is firmly in the mutilation-and-destruction camp regarding The Magnificent Ambersons (he calls Wise, Moss and George Schaefer “partners in crime”), but even he admits that there was never a time when anyone connected with it could honestly say, “It’s perfect; don’t change a thing.” Welles’s new contract entitled him to edit the picture through its first preview, which had been a disaster. After that came the changes — and like it or not, the farther Wise and Moss took the picture from Welles’s last edit, the better the previews were received. Callow relates an unconfirmed anecdote about pages and pages of Welles’s telegrams going straight into the wastebasket, the phone from Brazil ringing on and on with no one bothering to answer. Enough has survived in RKO archives to suggest that sort of thing wasn’t common, but it does seem that Welles’s demands were looking more irrelevant and less helpful to those back home. Moss later said, “If only Orson could communicate his genius by telephone”; Robert Wise expressed similar sentiments to me. He and Moss and Mark Robson wanted to follow Welles’s wishes, but the bottom line was Orson wasn’t there — in Pomona or in Hollywood.

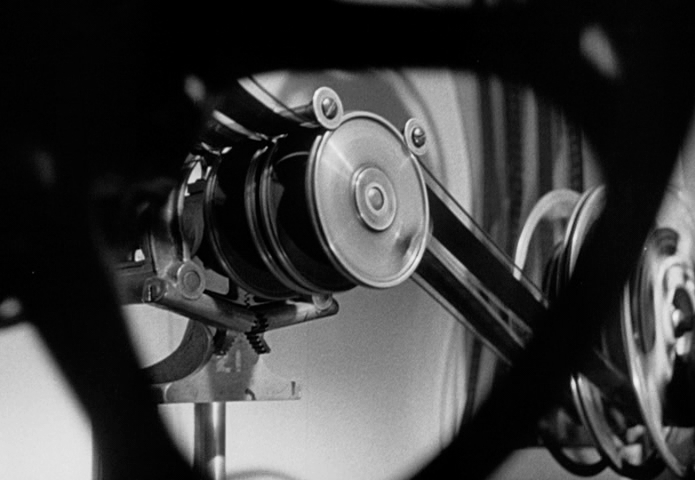

Robert Wise was under a threefold mandate: (1) from himself, preserve the spirit (and as much of the letter as possible) of Welles’s (and Tarkington’s) Ambersons; (2) from George Schaefer, get the picture into releasable form; and (3) from Charles Koerner, keep it to no more than 90 minutes. In the end, Wise had to do more than simply assemble the picture. He had to edit it — in the literary, Maxwell-Perkins-to-Thomas-Wolfe sense of the word. In later years, as the auteur theory took hold, this would be considered the crowning effrontery.

And yet. A comparison of Prof. Carringer’s reconstruction with the release version gives the lie to the notion so snidely implied in Peter Bogdanovich’s Bryan Foy anecdote — the idea that 40 minutes were cut thoughtlessly, at random. The cutting may seem drastic in places — especially to Welles, seeing the hard-won ball sequence, which he (mis)remembered as “one reel without a single cut”, shortened from 12 minutes 25 seconds to 6 minutes 56 seconds — but it’s not random. Wise followed the compromise plan worked out in late March with Jack Moss and Joseph Cotten, with a few differences. He kept in the kitchen scene but ended it before George (and Tim Holt) began raving in the rain about the new construction; and he retained the bathroom scene between George and Jack but trimmed George’s melodramatic overreaction (“unspeakable”, “monstrous”, “horrible”). Both of these moves, if they didn’t exactly create sympathy for George, at least helped keep Tim Holt’s performance from going over the top.

And Wise replaced the boarding house scene with the new one between Eugene and Fanny in the hospital corridor. Admittedly, this scene is hard to defend. It’s frankly so awkward — with its shallow-focus photography, Joseph Cotten’s line readings a little too chipper, Agnes Moorehead’s expression a little too blissful — that I tend to believe it was directed by Jack Moss. Wise and Freddie Fleck did better with the added scenes they directed. But at least the new scene was more faithful to Tarkington, albeit an over-compensation for Welles’s somber, downbeat ending.

To be sure, there are lines, passages and scenes whose loss is regrettable; Robert Wise admitted that the 132-min. cut was superior to what was finally released. But running much over 90 minutes simply was not an option. In 1984, Welles complained to Barbara Leaming: “The plot of course was really what they took out. Using the argument of not central to the plot, what they took out was the plot…” Excuse me, but that is rich coming from the man who wanted to take out the end of the Amberson ball, the “big cut”, the Indian legend, and George’s auto accident, all to protect his long ballroom sequence and boarding house scene. If anyone tried to cut “plot” out of The Magnificent Ambersons, it was Orson Welles (Robert Wise is roundly denounced for what he cut, but never gets any credit for what Welles wanted to cut that he left in). In fact, with two exceptions, nothing essential in Booth Tarkington’s novel is left out of the picture as it was finally released.

The first exception is the ruinous investment in the headlight company by Major Amberson, Uncle Jack and Fanny. In the release version there are only two rather cryptic references to it, with no explanation. But the only other mention in the cutting continuity is in the second porch scene, which not even Welles ever wanted to keep (possibly because of Richard Bennett’s struggle with the lines), so that would surely have been a problem no matter how long the release version ran. (Welles wanted to add some voice-over references in the closeup of the dying Major Amberson, but this was deemed too much information for that short, simple scene.)

The second exception is the portrayal of George’s “comeuppance”. In the finished film, Welles reads Tarkington’s narration in voice-over (“George Amberson Minafer had got his comeuppance…three times filled and running over…but the people who had so long for it were not there to see it…Those who were still living had forgotten all about it and all about him.”) But the scene is Isabel’s bedroom in the abandoned Amberson mansion, with George praying, “Mother, forgive me! God, forgive me!” In Tarkington’s novel, the comeuppance comes later, in his and Fanny’s new boarding house, when George consults the book of the city’s 500 most important families and finds nothing between “Allen” and “Ambrose”. That is Prince George’s comeuppance: the sudden knowledge that he and his whole family are, in the great scheme of things, not worth mentioning. It would have been a simple matter to include it, but Welles never shot it, never even wrote it into his screenplay.

An instructive (and nearly simultaneous) comparison is to look at what happened over at Paramount to the picture Preston Sturges wrote and shot with the title Triumph over Pain, but which finally went out as The Great Moment. (I wrote about that one in detail here.) To be sure, The Great Moment was never going to be as good as The Magnificent Ambersons, but it was going to be a lot better than it turned out, and contrasting it with Sturges’s published script shows clearly that the men who took it away and cut it didn’t know what they were doing — and didn’t care. The same comparison with Ambersons shows that Robert Wise et al. did care, and did know what they were doing.

Anyone willing to shell out 60 bucks for Prof. Carringer’s reconstruction can see that there’s really no “aha!” moment in the reconstructed version, no scene that clearly says “This absolutely should have been left in.” But the fact that the reconstruction is “a print-on-demand volume” testifies that there’s no great demand for it. Most people instead fall in with Orson Welles’s 43-year tantrum over being ignored, and they call Wise’s editing of Ambersons a mutilation instead of what I think it truly is: one of the most heroic feats of film editing — against unique, almost overwhelming odds — in the history of Hollywood. The picture’s high esteem to this day (though often qualified with “even in its present form…”) testifies to how well Wise preserved the picture Orson Welles left in his hands on February 6, 1942.

I said it before and I’ll say it again: Robert Wise — besides being an Oscar-winning producer and director, National Medal of Arts and AFI Life Achievement Award recipient, and past president of the Academy and the Directors Guild — was the greatest film editor who ever picked up a pair of scissors.

It has to be said: Nobody alive (and blogging) has seen the 132 min. cut of The Magnificent Ambersons film. Mr. Wise who did see it in 1942 is quoted as saying it was a better picture than his final 88 min. edit. Mr. Welles would agree with Mr. Wise on this, and add that it's indeed Chekov! Mr. Callow would agree with all of the above and I surely would agree with Mr. Callow! My point is Mr. Lane is entitled to his Minority Opinion, but it's not of much value because he has not seen Mr. Welles final picture, with his final edits, and final music and other post-production values included. Even if the Rio answer print was found, and in useable condition, it will never have the final and complete Orson Welles artistry attached to it. It seems Welles' own failings harmed his movie career more than any other person or group. He was self-destructive, but only partialy. Like an explosive volcano creating some really beautiful stones while doing much damage to himself.

Page, I'll be interested to see what Kim does with Ambersons for your Horseathon — the family's trusty Pendennis was certainly a minor character, but the transition from horses to automobiles was definitely a major theme!

Jim,

I was thrilled with TCM aired TMA recently and I've now got it sitting on my DVR. Was waiting until I read your last of your series and went back through and read from the beginning. (I took notes! Ha HA)

Looking forward to watching it again this weekend with fresh new eyes.

Thanks for entertaining us with your very in depth series. I do hope you'll choose another of Orson's films to look at.

Genius!

Oh and Kim chose TMA for my Horseathon! Hmmm, I wonder where she got the inspiration? : )

Page

Kim, thanks for sticking with it to the end; I realized early on that I'd be flying in the face of 70 years of conventional wisdom, so I'd better line my duckies up good and proper. I think you hit the nail pretty much on the head about Welles; certainly he wasn't always the talk-show charmer we later knew from Dick Cavett and Johnny Carson. (Have you seen Christian McKay in Me & Orson Welles? An amazing performance that really captures what he must have been like young and full of piss and vinegar; don't know how it missed an Oscar nomination.)

William, I think you're new here, so welcome; hope you'll return often! And thanks for the kind words; it has been a long strange trip, hasn't it?

What a wonderful coda to a "Magnificent" series! Thank you so much for taking us on this trip…every chapter was highly anticipated by us, and the conclusion did not leave us wanting. While Welles' considerable talents cannot be denied, this was one occasion when he merited his "comeuppance". Can't wait to see what you have next for us! Thanks again!

And so it ends. So much work went into this, Jim, you should be proud. Orson Welles may have been a true artist, but he was also a jackass!