Crazy and Crazier, Part 1

This post has grown in the planning, to the point where I’m putting it up in two parts (maybe more; we’ll see how things shake out). I have an epic tale to tell, nothing less than the rise and fall of the Hollywood musical, as reflected in the screen career of a single property: Girl Crazy, the 1930 Broadway hit with songs by George and Ira Gershwin, book by Guy Bolton and John McGowan.

This post has grown in the planning, to the point where I’m putting it up in two parts (maybe more; we’ll see how things shake out). I have an epic tale to tell, nothing less than the rise and fall of the Hollywood musical, as reflected in the screen career of a single property: Girl Crazy, the 1930 Broadway hit with songs by George and Ira Gershwin, book by Guy Bolton and John McGowan.Girl Crazy has been made into a movie more times than any other Broadway musical. Musical remakes have never been entirely unheard of, especially with early sound titles as talkie technology improved (Good News 1930 and ’47; The Vagabond King ’30 and ’56) or when a studio like MGM couldn’t think of anything better to do with its talent pool (Rose Marie ’36 and ’54, The Merry Widow ’34 and ’52 — the latter with Lana Turner, no less). Plus, of course, there have been any number of TV versions of musicals — live, taped and filmed — over the decades. Still, in Hollywood one-musical-one-movie has pretty much been a hard-and-fast rule. In that environment, Girl Crazy is unique — three movies, at three distinct stages of Hollywood musical history. I’ll come to each one in turn, but first a few words about the show itself.

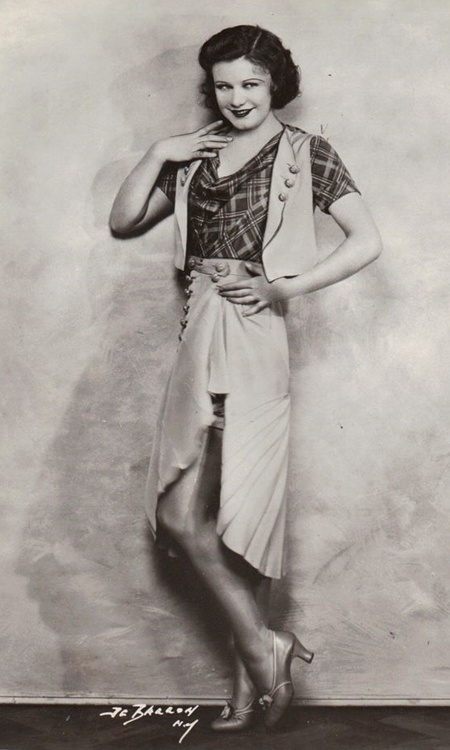

Girl Crazy opened on Broadway on October 14, 1930 and was an immediate smash; the buzz had been terrific ever since its out-of-town tryout in Philadelphia. Much of the buzz — and nearly all of it after the New York opening — was about a 22-year-old stenographer-turned-cabaret singer from Queens making her Broadway debut in one of the show’s secondary roles. Ethel Merman (that’s her with William Kent, who played her gambler husband) didn’t sing a note for most of the first act, and the audience had about decided she was just one of those non-singing comic supports with good timing and a way with a snappy line. Then in the last scene of Act I she came out and launched into “Sam and Delilah”, the Gershwins’ bluesy pastiche riff on “Frankie and Johnny”. The audience was knocked back in their seats: “Whoa! Where did this come from?” Then almost immediately she hit them again with a song George and Ira might almost have written with her voice in mind (though they didn’t): “I Got Rhythm”. That one set the crowd roaring loud enough to bring down the ceiling of the Alvin Theatre. There was an encore, then another, and another — more than anyone would be able to remember later. It was one of the most amazing one-two punches in Broadway history. By intermission that first night, Ethel Merman was the new queen of the American musical, a position she wouldn’t relinquish for 36 years.

Merman’s debut alone was enough to make Girl Crazy‘s opening a Broadway landmark, but there was more. Others present that night wouldn’t make it big until later, but the fact that they were there at all is enough to make you pray for time travel. For starters, there was the man who put together the pit orchestra: Ernest Loring “Red” Nichols, age 25, one of the busiest musicians in town. He was an accomplished cornetist who could play equally well “hot” and “straight”, and he had already made hundreds of Dixieland recordings for Brunswick Records, usually with an ad hoc band billed as Red Nichols and his Five Pennies.

Merman’s debut alone was enough to make Girl Crazy‘s opening a Broadway landmark, but there was more. Others present that night wouldn’t make it big until later, but the fact that they were there at all is enough to make you pray for time travel. For starters, there was the man who put together the pit orchestra: Ernest Loring “Red” Nichols, age 25, one of the busiest musicians in town. He was an accomplished cornetist who could play equally well “hot” and “straight”, and he had already made hundreds of Dixieland recordings for Brunswick Records, usually with an ad hoc band billed as Red Nichols and his Five Pennies.Nichols was a good judge of talent, too, and was well-suited to the jazz flavored music George Gershwin was writing for Broadway. Nichols had found the musicians to play the previous Gershwin show, Strike Up the Band, and he did the same for Girl Crazy. In the pit on opening night under George Gershwin’s baton (standing in that one night for conductor Earl Busby) were, among others, Nichols and Charlie Teagarden on trumpet, Georgie Stoll and Glenn Miller on trombone, Benny Goodman and Larry Binyon on sax, and Gene Krupa on drums. Midway through Girl Crazy‘s run, Goodman had a falling out with Nichols and was fired, replaced by Jimmy Dorsey. All these men would be in demand, even famous, during the Big Band Era — Goodman and Miller would become immortal. Georgie Stoll went on to become a key man in the MGM music department (winning an Oscar in 1945 for Anchors Aweigh). So did Roger Edens, who moved from the pit to the role of Ethel Merman’s on-stage pianist when her keyboard man Al Siegel became ill on opening night and had to drop out of the show. Later, at MGM, Edens would be producer Arthur Freed’s right-hand man and a formative influence on the great MGM musicals of the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s.

Record producer Warran Scholl attended Girl Crazy several times, not only to see the show, but to hear the orchestra jam between acts. “During the intermissions,” he recalled, “they’d really turn the band loose, and you should have heard the hot stuff they played. It wasn’t like a regular pit band — more like an act within an act.”

Playing Girl Crazy‘s lead was 19-year-old Ginger Rogers, fresh from making her Broadway debut in Top Speed and creating a sensation purring “Cigarette me, big boy” in her first movie, Young Man of Manhattan. She had two of Girl Crazy‘s most enduring songs, “Embraceable You” and “But Not for Me”, and by all accounts handled them quite nicely. But lacking what Cole Porter later called Ethel Merman’s “golden foghorn” voice, she had to stand helplessly by while Ethel stole her thunder night after night; it would take the intimacy of the movie camera to coax her star into full bloom. (And here’s a fun fact: During rehearsals one of her dance numbers was not working exactly right, so producers Alex A. Aarons and Vinton Freedley asked a dancing star they knew to step in and refine the choreography as a favor, and he coached Ginger on the routine in the lobby of the Alvin during rehearsals. You guessed it: It was Fred Astaire.)

Playing Girl Crazy‘s lead was 19-year-old Ginger Rogers, fresh from making her Broadway debut in Top Speed and creating a sensation purring “Cigarette me, big boy” in her first movie, Young Man of Manhattan. She had two of Girl Crazy‘s most enduring songs, “Embraceable You” and “But Not for Me”, and by all accounts handled them quite nicely. But lacking what Cole Porter later called Ethel Merman’s “golden foghorn” voice, she had to stand helplessly by while Ethel stole her thunder night after night; it would take the intimacy of the movie camera to coax her star into full bloom. (And here’s a fun fact: During rehearsals one of her dance numbers was not working exactly right, so producers Alex A. Aarons and Vinton Freedley asked a dancing star they knew to step in and refine the choreography as a favor, and he coached Ginger on the routine in the lobby of the Alvin during rehearsals. You guessed it: It was Fred Astaire.)Rounding out the principal cast of Girl Crazy were its two nominal stars, comedians Willie Howard and William Kent, and juvenile lead Allen Kearns. (Understand, “juvenile” was a relative term in the theater of the day, denoting a romantic character type rather than age; think Dick Powell with Ruby Keeler. In fact, Kearns was 37, old enough to be Ginger Rogers’s father).

With George and Ira Gershwin providing the songs; Ethel Merman, Ginger Rogers and 35 beautiful chorus girls on stage; and Red Nichols, Benny Goodman, Glenn Miller, Gene Krupa, Georgie Stoll, Roger Edens et al. supplying the music, Girl Crazy — over and above the hit it made with audiences at the time — represents to us looking back an almost mind-boggling nexus of the burgeoning American pop music scene. If anyone ever does invent that time machine, the Alvin Theatre between October 14, 1930 and June 6, 1931 (when Girl Crazy closed) is liable to wind up bulging with millions of time-traveling buffs eager to experience the magic for themselves.

The magic act did have its flat spots, mainly in the form of the book by Guy Bolton and John McGowan — a weakness recognized at the time by even the most rhapsodic reviewers. The “integrated” musical, where the songs grow out of a show’s plot and characters, wasn’t unheard of then (e.g., Show Boat), but it was far from the gold standard it would become in the age of Rodgers and Hammerstein (and remain ever after). More common was the musical comedy, where the book consisted mainly of a series of elaborate, even labored, jokes and set-ups for the next song. So it was with Girl Crazy: The music presents one show, the book another, in which (as historian Ethan Mordden aptly put it) “songs drop in like guests at an open house.” In 1991, when Broadway director Mike Ockrent undertook a revival of the show, he found the book so irrelevant (and by then so dated) that a new one was commissioned from playwright Ken Ludwig. Then, figuring that since they were writing a new book anyway, they might as well embellish the score as well, they imported a raft of other Gershwin songs and came up with a whole “new” show, Crazy for You. It was another smash, running just short of four years.

Ockrent and Ludwig could afford to ignore Girl Crazy‘s book, but I can’t; you’ll need a grasp of the show’s original plot (such as it was) before we fall to discussing the various tweaks and prods it got once it went to Hollywood. So, as quick-and-painless as I can make it, here goes:

Act I opens in the sleepy village of Custerville, Arizona, where the only excitement comes when somebody shoots the sheriff, which happens about every other week. Into this rides New York playboy Danny Churchill (Allen Kearns), in a taxicab driven by Gieber Goldfarb (Willie Howard) with $742.30 on the meter (UPDATE 5/10/24:That’s about $13,882.88 in today’s dollars). Danny’s tycoon father, appalled at his girl-crazy Manhattan high jinks, has banished him to Custerville, where there isn’t a woman for 50 miles; Danny is to stay out of trouble by managing Buzzards, the family ranch. But there is a woman in town: Molly Gray (Ginger Rogers), the local postmistress, and Danny falls for her on sight. Homesick for the fast life, he decides to turn Buzzards into a dude ranch, and soon it’s a real hot spot. Among the tourists it attracts are gambler Slick Fothergill (William Kent) and his wife Kate (Ethel Merman). But it also brings Tess Harding, Danny’s old girlfriend, and Sam Mason, the guy Danny beat out for Tess’s affections. Sam decides to get Danny back by wooing Molly away, which, after the typical misunderstandings, he does, persuading her to go over the border with him to San Luz, Mexico. Meanwhile, another sheriff has been assassinated, and Gieber Goldfarb runs for the vacant office against local tough Lank Sanders. When he wins, he opts to decamp to San Luz himself to flee Lank’s wrath; Slick joins him, bringing two visiting girls along to keep them company. The Act I finale finds Danny dejected at his rift with Molly, Kate consoling him (not yet knowing that her husband has gone philandering to Mexico), and everybody else on their way to San Luz.

Act II finds half the population of Custerville in San Luz. Danny finds Molly, bids her farewell and wishes her all the best with Sam; only after he leaves does she realize her true feelings for him, and now she fears the knowledge has come too late. But when she learns that Sam has registered them at the local hotel as husband and wife, she realizes what a cad he is and runs to Danny’s arms. Outraged, Danny blurts a threat against Sam that returns to bite him when Sam is assaulted and robbed and Danny is accused of the crime. Meanwhile, Kate confronts her cheating husband. Eventually — jeez, let’s cut to the chase — Gieber exposes Lank and his henchman Pete as the men who robbed Sam, Kate and Slick reconcile, Danny and Molly are reunited, and everybody presumably lives happily ever after back in Custerville.

Act II finds half the population of Custerville in San Luz. Danny finds Molly, bids her farewell and wishes her all the best with Sam; only after he leaves does she realize her true feelings for him, and now she fears the knowledge has come too late. But when she learns that Sam has registered them at the local hotel as husband and wife, she realizes what a cad he is and runs to Danny’s arms. Outraged, Danny blurts a threat against Sam that returns to bite him when Sam is assaulted and robbed and Danny is accused of the crime. Meanwhile, Kate confronts her cheating husband. Eventually — jeez, let’s cut to the chase — Gieber exposes Lank and his henchman Pete as the men who robbed Sam, Kate and Slick reconcile, Danny and Molly are reunited, and everybody presumably lives happily ever after back in Custerville.Girl Crazy was still going strong when it closed on June 6, 1931; producers Aarons and Freedley had been unable to persuade Willie Howard (who for some inexplicable reason they considered indispensable) to sign on for a second season. In the meantime, the movie rights to the show had been sold to RKO Radio Pictures for $33,000.

And I think that’s about enough to digest for one session. When we come back, we’ll look at what happened when the show, like Danny Churchill himself, went west — not to sleepy Arizona, but all the way to the bustling environs of Tinsel Town.

Thanks, Dorian; I'll save you and Vinnie seats on that time machine if you'll save me a seat on the alternate-universe machine to go see Zero Mostel (and Gene Wilder?) on stage in THE PRODUCERS…