Reading the stories that Herminie Templeton (later Kavanagh) published in 1903 as

Darby O’Gill and the Good People, it’s easy to understand why Walt Disney wouldn’t give up on the idea of bringing them to the screen — but it’s also easy to see why it took Lawrence Edward Watkin eleven years to fashion them into a screenplay. With titles like “The Convarsion of Father Cassidy”, “How the Fairies Came to Ireland” and “The Banshee’s Comb”, the stories are short on incident — more anecdotes that stories, really. Also, as the word “Convarsion” suggests, they are written in a (literally) pronounced Irish dialect — it takes a while to realize that “craychur” means “creature”, “sthrame” is “stream”, “imaget” is “immediate”, and so on.

But once you adjust to these idiosyncracies (especially if you can assume the accent and read the stories aloud), there’s an unassuming poetry to the tales that can sometimes take your breath away. Describing one fine morning, the narrator (it’s hinted that he’s a Kilkenny cabbie and the son of a cousin of Darby’s) says, “‘Twas one of those warm-hearted, laughing autumn days which steals for a while the bonnet and shawl of the May.” What more do we need to hear to know exactly the sort of day it was?

Another time, Darby O’Gill’s wife Bridget boasts to other wives of the village that her husband is so brave that he doesn’t fear to leave the house on Halloween Night, when “all the worruld” knows that ghosts are afoot. To prove her point (and save face), even as a fierce storm rages that very night, Bridget resolves to cajole Darby into taking “a bit of tay” to poor young Eileen McCarthy, who lies near death. At first Darby resists — “We have two separate ways of being good. Your way is to scurry round an’ do good acts. My way is to keep from doing bad ones. An who knows which way is the betther one. It isn’t for us to judge.” But when he finally agrees to go out, a relieved Bridget encourages him in this lovely passage:

“Oh, ain’t ye the foolish darlin’ to be afeard,” smiled Bridget back at him, but she was serious, too. “Don’t you know that when one goes on an errant of marcy a score of God’s white angels with swoords in their hands march before an’ beside an’ afther him, keeping his path free from danger?” With that she pulled his face down to hers, and kissed him as she used in the old courting days.

There’s nothing puts so much high courage and clear steadfast purpose in a man’s heart, if it be properly given, as a kiss from the woman he loves. So, with the warmth of that kiss to cheer him, Darby set his face against the storm.

There are countless rough-jeweled passages like that in Mrs. Kavanagh’s prose — I laughed out loud at “One could have scraped with a knife the surprise off Darby’s face” — but you get the idea. How to preserve the delicate humor of the stories, the palpable sense of a happy home and hearth, the simple yet ardent faith, the merry yet mischievous friendship between Darby and King Brian, was what Lawrence Edward Watkin wrestled with between assignments from the day Disney hired him.

Because Darby O’Gill is rarely considered one of Disney’s major pictures, there is scant published documentation of its development and production. Two major biographies, Neal Gabler’s Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination and Michael Barrier’s The Animated Man, have only two cursory mentions between them. Peter Ellenshaw’s coffee-table memoir Ellenshaw Under Glass goes into detail about his visual effects work (which I covered in Part 2), and he says that both Bill Walsh and Don DaGradi (who later shared an Oscar nomination for their Mary Poppins screenplay) worked on the script. (In the finished picture DaGradi is credited only for “Special Art Styling”, Walsh not at all. It may be that Walsh — like DaGradi, one of Disney’s most trusted lieutenants — worked uncredited on the script; it’s also possible that Ellenshaw, writing in 2003, conflated Darby O’Gill with his later work with Walsh and DaGradi on Mary Poppins.)

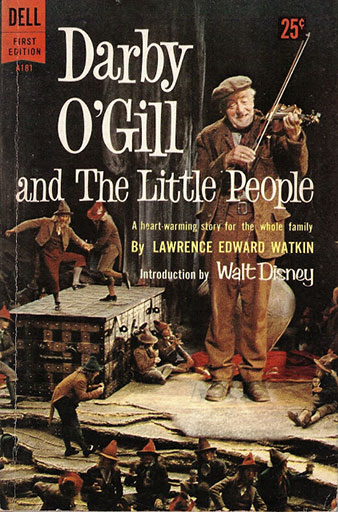

We do, at least, have testimony from Walt Disney himself, in the form of his introduction to the Darby O’Gill novelization. (The intro was ghost-written, no doubt, but it’s a cinch it wouldn’t have gone to the printer until Walt approved it.) He says that it was “in 1945, I believe” that Herminie Kavanagh’s stories first came to his attention, prompting a trip to Ireland to get a feel for the land.

Disney did indeed visit Ireland and Great Britain in November 1946, and again for a longer stay from June to August ’49. His leprechaun movie might have been on his mind both those times. In ’46 he had spoken to Hollywood columnist Hedda Hopper about plans for Alice in Wonderland (to be done with a live-action Alice played by little Luana Patten of Song of the South, and set in an animated Wonderland) as well as for The Little People, to be set in Ireland.

But it’s unlikely that Herminie Kavanagh’s Darby O’Gill stories were foremost in his mind even then. The Disney Studio was drifting after the end of World War II — strapped for money, still recovering from the bitter trauma of a strike in the early ’40s (which Disney took very personally), and uncertain how to move forward. Of more immediate concern, no doubt, was how the cash-poor studio could make use of the millions of pounds sterling that had piled up from features and shorts playing in the U.K. during the war; money that Disney sorely needed but which, due to currency restrictions imposed by Parliament, couldn’t be taken out of the country.

|

| DR. JAMES HAMILTON DELARGY |

Is it possible that Disney considered shooting something like Darby O’Gill in Northern Ireland, where his British pounds would be at his disposal? Probably not; in any case, those pounds wound up being pumped into Disney’s first all-live-action feature, Treasure Island (’50). Other British-shot pictures would follow: The Story of Robin Hood and his Merrie Men (’52), The Sword and the Rose, and Rob Roy: The Highland Rogue (both ’53). But nothing with leprechauns.

Between those two visits, in 1947, Disney hired Larry Watkin to adapt Kavanagh’s stories, making sure “that he too should take a leisurely sojourn through Ireland, talking with the old storytellers and absorbing the spirit of the place”. (Did Watkin make this trip while Disney was there during the summer of ’49? Maybe; the record is unclear.) Disney goes on to say that Watkin consulted with Drs. James Hamilton Delargy and Sean O’Sullivan, the director and chief archivist (respectively) of the Irish Folklore Commission in Dublin. (Curiously enough, the good doctors were able to show Watkin their files on no fewer than 54 versions of the old folktale — Death trapped in an old man’s apple tree — that had inspired his novel On Borrowed Time.)

“In spite of the richness of the material,” Disney remembered, “or maybe because of its abundance, the story did not jell that year”. Other projects intervened. Watkin got sidetracked into scripting all four of Disney’s British-made features, plus several others back in the States. Disney, of course, became preoccupied with both Disneyland (the TV series) and Disneyland (the park in Anaheim). It was nearly a decade before the two men returned to what Disney called “the Irish story”. “This time,” he remembered, “it worked”.

Without venturing into the archives of the Disney Studios, I can’t know what stages Watkin went through to, as they say, “break the back” of Walt’s leprechaun picture. (I’m sure the information is somewhere in those files; the Disney people never threw anything away. Maybe I’ll get a chance to find out someday.) All I have to go on is a comparison of Mrs. Kavanagh’s original stories with the one that appears on the screen, and Larry Watkin, while retaining the names of Darby O’Gill and King Brian Connors, took a wealth of liberties.

The liberties began with the mountain location of King Brian’s underground castle. Herminie Kavanagh gave it as Slieve-na-mon (usually spelled without the hyphens), a 2,363-ft. peak in southern County Tipperary, near Clonmel. Watkin moved King Brian’s court about 22 miles southwest, to Knocknasheega in County Waterford — possibly for its less cumbersome and more poetic-sounding name. But the change didn’t stop there; here’s a view of 1,404-ft. Knocknasheega as it is in real life…

…and here’s how it appears in Darby O’Gill (courtesy of the imagination of Larry Watkin and the palette of Peter Ellenshaw), crowned with the scattered ruins of a castle so ancient nobody remembers who built it. The ruins serve a dramatic as well as picturesque purpose; they become the scene of enchantment when the leprechauns cast their come-hither spell on Darby and — later, for a different reason — his daughter Katie. As you can see, there are no such ruins on the real Knocknasheega. There are in fact two prehistoric stone cairns on the peak and slopes of Slievenamon, but there is no fairy magic imputed to them by Irish folklore and they do not figure in any of the Kavanagh stories.

Darby O’Gill’s village has no name in Kavanagh; in the movie it’s Rathcullen. After an exhaustive Internet search, I could find no village by that name, only a real estate listing for a single house on a half-acre of land “nestling between Aherla [pop. 450] & Cloughduv [pop. 300] Villages” in County Cork. (There’s also a Web site for a Rathcullen Lounge in Killarney, County Kerry, which for all I know may have taken its name from the movie.) So let’s take it as given that Rathcullen and the neighboring village of Glencove are both creations of Lawrence Edward Watkin.

So are most of the characters. In the stories, Darby’s age is never mentioned, but his wife Bridget is still alive, his children (at least four of them) are still small, and the narrator often calls Darby “the lad”. Watkin made him an elderly widower with only his grown daughter Katie. While Darby’s livelihood is hardly hinted at in Kavanagh, in the movie he’s caretaker on the country estate of Lord Fitzpatrick (Walter Fitzgerald) — “but he retired about five years ago,” says his lordship, “didn’t tell me about it.” That’s why Lord Fitzpatrick has hired Michael McBride (Sean Connery) to replace him, intending to retire Darby on half pay, with free use of a small cottage on the property for the rest of his days. Darby wheedles his lordship into letting him break the news to Katie himself, and when Lord Fitzpatrick leaves, Darby introduces Michael to Katie as a new hired hand. Darby’s scheming to keep the truth from Katie as long as possible, along with his later kidnapping of King Brian, are the twin threads that will come together at Darby O’Gill‘s ghostly climax.

Watkin also provided something Herminie Kavanagh’s stories lacked: a couple of villains. Maybe “villains” is too strong a term; these two aren’t really wicked. But both of them are up to no good. First comes old Sheelah Sugrue, the village gossip and busybody (Estelle Winwood). Watkin’s novelization says, “She was the sort of old woman who in olden days made witch-burning flourish. One look at her and you would want the custom revived.” English-born Estelle Winwood was 75 when she made Darby; she had been a professional actress since 1903 and had made her Broadway debut in 1916. This was her sixth feature film since 1933 (she preferred the stage but did a lot of TV in the ’40s and ’50s), and she would go on to become the oldest working actress — or actor, for that matter — in the world. She made her last appearance in an episode of Quincy M.E. when she was 97 and died in 1984 at the age of 101. In Darby, her meddlesome Sheelah Sugrue is the proud mother of…

Pony Sugrue (Kieron Moore), Rathcullen’s roisterer, bully-boy, and all-around ne’er-do-well. (The character would resurface a generation later, little changed, in the form of Gaston in Disney’s Beauty and the Beast.) Pony’s mother regards him as the natural heir to Darby’s job (a job she doesn’t know Michael McBride already has), while Pony himself regards Katie O’Gill as his personal property, any other man who looks at her doing so at his own peril. Kieron Moore was another one of the authentic Irishmen in Darby‘s cast. He began his acting career as a teenager with Dublin’s Abbey Players; he was soon placed under contract by British producer Alexander Korda, who predicted great stardom for him. The stardom never quite materialized despite solid work in over 50 movies and TV series, and he retired from acting in 1974 to devote himself to social activism on behalf of the Third World. He died in 2007, age 82.

Darby O’Gill and the Little People‘s director was Robert Stevenson, who by 1959 was becoming pretty well established as the Disney Studio’s house director. Stevenson began directing in his native England in 1932, where his pictures included the 1937 British version of King Solomon’s Mines. He came to Hollywood in 1940 to direct Tom Brown’s School Days for the short-lived The Play’s the Thing unit at RKO, then worked for RKO again on Forever and a Day, the 1943 wartime morale-builder about multiple generations in an English family. After that it was over to 20th Century Fox for Jane Eyre with Orson Welles and Joan Fontaine, a movie that remains the yardstick for measuring subsequent adaptations of Charlotte Bronte’s novel (others may be judged better, but all are compared first to Stevenson’s).

Stevenson’s first picture for Disney was Johnny Tremain in 1957, followed later that year by Old Yeller — another yardstick movie, this time for boy-and-his-dog stories. Then three episodes of Disney’s Zorro TV series, then Darby O’Gill. Stevenson would go on to direct some of Disney’s most successful live-action pictures: Kidnapped (1960), The Absent-Minded Professor (’61), Son of Flubber (’63), and Walt Disney’s (and Stevenson’s) most glittering achievement, Mary Poppins (’64). After Disney’s death Stevenson would remain at the studio for The Love Bug (’68), Bedknobs and Broomsticks (’71), and Herbie Rides Again (’74), among others. Not all of Stevenson’s pictures were estimable achievements — The Misadventures of Merlin Jones (’64), The Monkey’s Uncle (’65) — but nearly all of them came in on time, under budget, and profitable.

In Part 4 I’ll talk about some elements of Irish folklore that appear in both Herminie Kavanagh’s stories and, distilled and transformed by Lawrence Edward Watkin’s own imagination, in the finished picture; and I’ll wind up my case for why I think Darby O’Gill and the Little People deserves to stand proudly beside Snow White, Fantasia, Mary Poppins, and just about any other Walt Disney picture you care to name.

In 1962, if I had known that the actor playing James Bond was the same actor who played Michael McBride in Darby O’Gill and the Little People, I might have taken the trouble to see Dr. No sooner than I did. But in all the publicity surrounding the screen debut of Ian Fleming’s secret agent, and the handsome young discovery of producers Harry Saltzman and Albert Broccoli, there was scant mention (if any) of the picture Sean Connery had made for Walt Disney three years earlier. Small wonder: Darby O’Gill was a flop.

In 1962, if I had known that the actor playing James Bond was the same actor who played Michael McBride in Darby O’Gill and the Little People, I might have taken the trouble to see Dr. No sooner than I did. But in all the publicity surrounding the screen debut of Ian Fleming’s secret agent, and the handsome young discovery of producers Harry Saltzman and Albert Broccoli, there was scant mention (if any) of the picture Sean Connery had made for Walt Disney three years earlier. Small wonder: Darby O’Gill was a flop.