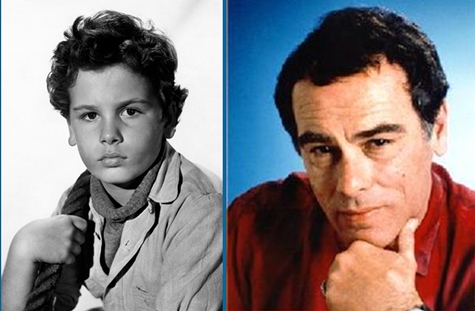

While preparing my post on the first day of this year’s Cinevent 52 in Columbus, Ohio, I learned of the passing of Dean Stockwell at his home in Ranchos de Taos, New Mexico on November 7 at the age of 85. Stockwell, boy and man, was one of the finest actors who ever faced a movie camera, yet he never quite received the recognition or accolades he deserved — no Oscar (“real” or honorary), no Presidential Medal of the Arts, no Kennedy Center Honors. All he ever managed was a couple of Golden Globes (which everybody knows are worthless); ensemble acting awards at Cannes for Compulsion in 1959 (shared with Bradford Dillman and Orson Welles) and Long Day’s Journey Into Night in 1962 (with Katharine Hepburn, Ralph Richardson and Jason Robards Jr.); and a star on that crummy Hollywood Walk of Fame. Nevertheless, he was one of our best, so steady, so reliable, and around so long that we could become lulled into believing he’d always be there.

While preparing my post on the first day of this year’s Cinevent 52 in Columbus, Ohio, I learned of the passing of Dean Stockwell at his home in Ranchos de Taos, New Mexico on November 7 at the age of 85. Stockwell, boy and man, was one of the finest actors who ever faced a movie camera, yet he never quite received the recognition or accolades he deserved — no Oscar (“real” or honorary), no Presidential Medal of the Arts, no Kennedy Center Honors. All he ever managed was a couple of Golden Globes (which everybody knows are worthless); ensemble acting awards at Cannes for Compulsion in 1959 (shared with Bradford Dillman and Orson Welles) and Long Day’s Journey Into Night in 1962 (with Katharine Hepburn, Ralph Richardson and Jason Robards Jr.); and a star on that crummy Hollywood Walk of Fame. Nevertheless, he was one of our best, so steady, so reliable, and around so long that we could become lulled into believing he’d always be there.

I can think of no more fitting tribute to the late Mr. Stockwell than to reprint my 2010 post on the picture in which the 12-year-old Dean gave the finest performance of his 70-year career: Henry Hathaway’s Down to the Sea in Ships (1949).

Farewell, Dean Stockwell, and thanks for the memories.

* * *

In 1949 Henry Hathaway made one of the best movies of his long career. In it, his three stars, Richard Widmark, Lionel Barrymore and Dean Stockwell (and for that matter, most of the supporting cast) each gave one of his own best performances. Down to the Sea in Ships is in fact one of the finest movies ever to come out of the Hollywood studio system, and almost nobody has ever heard of it.

In 1949 Henry Hathaway made one of the best movies of his long career. In it, his three stars, Richard Widmark, Lionel Barrymore and Dean Stockwell (and for that matter, most of the supporting cast) each gave one of his own best performances. Down to the Sea in Ships is in fact one of the finest movies ever to come out of the Hollywood studio system, and almost nobody has ever heard of it.

I know I run the risk of overselling the product here, but I simply don’t understand why Down to the Sea in Ships isn’t one of the best-loved movies of all time. When the talk turns to the great seafaring stories of the screen — Treasure Island, Mutiny on the Bounty, Captains Courageous, Moby Dick et al. — it’s a mystery to me why Down to the Sea in Ships never comes up. If there are such things as flawless movies, and there surely are, Henry Hathaway’s Down to the Sea in Ships is one of them.

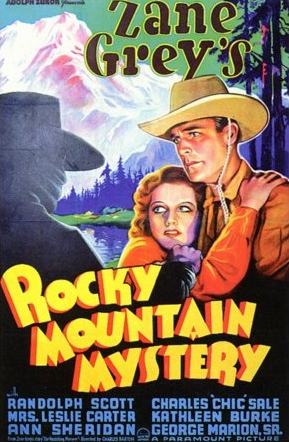

I say “Henry Hathaway’s” to distinguish this picture from the other Down to the Sea in Ships, from 1922. That one made a star out of Clara Bow, and curiously enough, it’s available on home video — no doubt because it’s in the public domain, while Hathaway’s picture is still under copyright and quarantined in the 20th Century Fox vault. In the 1960s and ’70s it was the other way around: Down to the Sea in Ships (1922) was gone and long forgotten, but if your local TV station had a decent film library and you were willing to stay up till two or three in the morning, you could count on seeing Down to the Sea in Ships (1949) two or three times a year.

Before we leave the subject of Clara Bow’s breakout vehicle for good, let’s get one point clear: Wikipedia says that the 1922 picture “was remade by Twentieth Century Fox in 1949,” but — well, that’s Wikipedia for you. (Whoever wrote the article didn’t even know that it’s “20th Century Fox,” not “Twentieth.”) In fact, there is no connection whatsoever between the two pictures — other than the fact that they both deal with whaling ships out of New Bedford, Mass., and they both take their title from Psalm 107:23 (“They that go down to the sea in ships, that do business in great waters…”). These aren’t two versions of the same story, they’re two different movies with the same title; henceforth, when I use the title, I’ll be talking about only one of them.

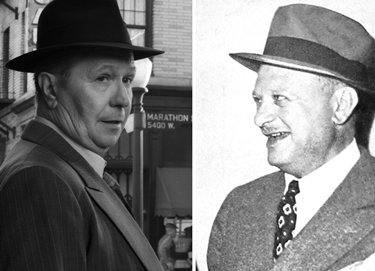

After the war, Zanuck reactivated the project and handed it over to producer Louis D. (“Buddy”) Lighton and director Hathaway. Both men were working for Fox now, but they had been paired before in the 1930s at Paramount: Lighton had produced the Shirley Temple vehicle Now and Forever, The Lives of a Bengal Lancer, and Peter Ibbetson, all of which Hathaway directed. The first draft of the script was by Sy Bartlett — that’s him at right — born Sacha Baraniev in Russia (now Ukraine) in 1900 but raised in America from the age of four. Originally a newspaper reporter, he became a screenwriter for various studios in the ’30s, but he was noted more for hobnobbing in Hollywood society, hosting Sunday barbecues, and the occasional gossip-column appearance. He served with the U.S. Army Air Corps during World War II, then returned to Hollywood and a job at Fox. At the time that he took his first cut at Down to the Sea in Ships, Bartlett’s most memorable work was still ahead of him: he later turned his wartime experience into the novel and screenplay Twelve O’Clock High (1949) for director Henry King and star Gregory Peck.

After the war, Zanuck reactivated the project and handed it over to producer Louis D. (“Buddy”) Lighton and director Hathaway. Both men were working for Fox now, but they had been paired before in the 1930s at Paramount: Lighton had produced the Shirley Temple vehicle Now and Forever, The Lives of a Bengal Lancer, and Peter Ibbetson, all of which Hathaway directed. The first draft of the script was by Sy Bartlett — that’s him at right — born Sacha Baraniev in Russia (now Ukraine) in 1900 but raised in America from the age of four. Originally a newspaper reporter, he became a screenwriter for various studios in the ’30s, but he was noted more for hobnobbing in Hollywood society, hosting Sunday barbecues, and the occasional gossip-column appearance. He served with the U.S. Army Air Corps during World War II, then returned to Hollywood and a job at Fox. At the time that he took his first cut at Down to the Sea in Ships, Bartlett’s most memorable work was still ahead of him: he later turned his wartime experience into the novel and screenplay Twelve O’Clock High (1949) for director Henry King and star Gregory Peck.

Without access to what records might be in the 20th Century Fox archives, it’s impossible for me to say exactly how credit for Down to the Sea‘s script should shake out — which is a pity, because the script is a truly masterful piece of work; if the picture ever gets the kind of attention it has deserved for over 60 years, maybe someone will shed some light on the subject. The writing credit on screen reads “Screen Play by John Lee Mahin and Sy Bartlett; From a Story by Sy Bartlett,” which matches the general drift of the two writers’ careers: story was Bartlett’s long suit, dialogue Mahin’s. Making an educated guess, I’d say Bartlett was responsible for Down to the Sea‘s distinctive blend of rousing adventure and psychological acuity, Mahin for the unerring cadence and vocabulary of the speech of 19th century New England whalermen. Or it may have been more complicated than that; Mahin gets top billing on screen, which suggests that his rewrite probably amounted to more than just touching up the dialogue.

Down to the Sea in Ships opens in New Bedford in the summer of 1887. The whaling ship Pride of New Bedford returns from a four-year voyage under the command of Capt. Bering Joy (Lionel Barrymore), the best whaler on the New England coast. He’s just about the oldest, too, though he shows no signs of being ready to retire from the sea. The reason for that is his 11-year-old grandson Jed (Dean Stockwell), the youngest in a line of the whaling Joy family that extends back “mighty nigh two hundred years.” Capt. Joy, though still on crutches from an injury that kept him bunk-ridden for much of the voyage, is unwilling to retire, at least until Jed is thoroughly brought up in the ways of the sea and can continue the family tradition. Jed himself is (if you’ll pardon the expression) entirely on board with this; he loves the seafaring life, the only life he’s ever known. He’s spent the last four years — nearly half his life — as his grandfather’s cabin boy, and is now eager to ship out again as an apprentice member of the fo’c’sle crew.

Down to the Sea in Ships opens in New Bedford in the summer of 1887. The whaling ship Pride of New Bedford returns from a four-year voyage under the command of Capt. Bering Joy (Lionel Barrymore), the best whaler on the New England coast. He’s just about the oldest, too, though he shows no signs of being ready to retire from the sea. The reason for that is his 11-year-old grandson Jed (Dean Stockwell), the youngest in a line of the whaling Joy family that extends back “mighty nigh two hundred years.” Capt. Joy, though still on crutches from an injury that kept him bunk-ridden for much of the voyage, is unwilling to retire, at least until Jed is thoroughly brought up in the ways of the sea and can continue the family tradition. Jed himself is (if you’ll pardon the expression) entirely on board with this; he loves the seafaring life, the only life he’s ever known. He’s spent the last four years — nearly half his life — as his grandfather’s cabin boy, and is now eager to ship out again as an apprentice member of the fo’c’sle crew.Unfortunately, the decision may be taken out of both their hands. The whaling firm’s insurance company refuses to cover Capt. Joy; moreover, Massachusetts law will not allow Jed to return to sea unless he can pass an exam covering the four years of schooling he missed while he was away. Fortunately, a sympathetic school superintendent (Gene Lockhart, in a warmhearted cameo) fudges Jed’s test results rather than disappoint the captain.

For his part, Dan Lunceford doesn’t care much for the look of Capt. Joy, nor for his sneering at Lunceford’s “book-learnin'” and his college degree in marine biology; only a sweetening of his percentage of the voyage’s profits persuades the younger man to ship out with Capt. Joy after all.

Once the Pride of New Bedford is out to sea, Capt. Joy plays his trump card. He tells Lunceford that he sees “the hand of Providence” in Lunceford’s presence on board. Jed was allowed to ship out, he says, only on the condition that his studies be continued, and Capt. Joy is hereby assigning Lunceford, in addition to his regular duties as first mate, to be Jed’s tutor during his off-duty hours. In this way, the crafty old mariner intends to kill two birds with one stone: he’ll see to Jed’s education, and he’ll keep Lunceford too busy to undermine his authority.

Lunceford has no choice but to accept the assignment, but he does so with ill grace. Resentful at what he regards as essentially a babysitting chore, he is impatient, sarcastic and dismissive. Resentful in turn, Jed is obstreperous and uncooperative. Lunceford decides Jed is just as ornery and pigheaded as his grandfather, and he give up the lessons as a waste of his time.

Stung, Jed applies himself and in time surprises Lunceford with answers to all the questions that had stumped him before. Lunceford suddenly approaches his duties as tutor in earnest, tailoring lessons more carefully to Jed’s quick and lively but unsophisticated intelligence. As the friendship grows between Jed and Lunceford, Capt. Joy begins — rightly or wrongly — to fear that his grandson’s respect and affection are drifting away from himself and attaching themselves to Lunceford; he responds to the unexpected competition by looking more carefully at Lunceford’s ideas, which he had formerly dismissed as not worth his attention. All this happens even as the Pride of New Bedford roams the waters of the South Atlantic, stalking and taking whales.

That’s about as much of the plot as I care to go into here; better that you should discover the rest for yourself. Down to the Sea in Ships isn’t available on home video*, but it does surface (pun intended) from time to time on the Fox Movie Channel, and it’s worth seeking out to discover how the three-generation, three-way relationship of Capt. Joy, Jed and Dan Lunceford plays itself out against the background of a perilous voyage contending with the forces of nature and the leviathans of the deep. Each of the three discovers qualities of strength and character in the others that he either never suspected or did not properly value at first. Each brings out the best in the other two, and allows the other two to bring out the best in him.

All this, mind you, while the movie does not skimp on action and high adventure. There are scenes of whale chases and boats lost at sea, suspenseful and beautifully shot (Joe MacDonald) and edited (Dorothy Spencer), with excellent special effects (Fred Sersen and Ray Kellogg). Capping it all is a climactic sequence in which the Pride of New Bedford runs aground on an iceberg in the fog near the horn of South America…

All this, mind you, while the movie does not skimp on action and high adventure. There are scenes of whale chases and boats lost at sea, suspenseful and beautifully shot (Joe MacDonald) and edited (Dorothy Spencer), with excellent special effects (Fred Sersen and Ray Kellogg). Capping it all is a climactic sequence in which the Pride of New Bedford runs aground on an iceberg in the fog near the horn of South America…

…with the crew struggling desperately to free themselves and repair the damage before the sea pounds their ship to splinters against the unforgiving ice. Not to mince words, it’s an absolutely brilliant action/suspense set piece. Amazingly enough, it was shot entirely in a soundstage tank on the Fox lot, but it’s spectacularly convincing and harrowing for all that.

Down to the Sea in Ships was Lionel Barrymore’s last starring role, on loan from MGM. Once, when introducing Barrymore on a 1939 radio broadcast, Orson Welles referred to him as “the most beloved actor of our time.” It was probably an exaggeration, but not by much; Barrymore’s stock in trade was playing cantankerous old codgers with hearts of gold. Ironic, then, that the only role for which he’s widely remembered today is Old Man Potter in It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), one of the most thoroughly heartless characters in the history of movies. In his own day Barrymore was more closely identified with wise old Dr. Gillespie in MGM’s Dr. Kildare series, and with his annual holiday performances as Ebenezer Scrooge on radio. In fact, Barrymore had been slated to play Scrooge in MGM’s A Christmas Carol (1938) until he broke his hip in an auto accident. That injury landed him in a wheelchair, then advancing arthritis kept him there for the rest of his career — until Down to the Sea in Ships.

Down to the Sea in Ships was Lionel Barrymore’s last starring role, on loan from MGM. Once, when introducing Barrymore on a 1939 radio broadcast, Orson Welles referred to him as “the most beloved actor of our time.” It was probably an exaggeration, but not by much; Barrymore’s stock in trade was playing cantankerous old codgers with hearts of gold. Ironic, then, that the only role for which he’s widely remembered today is Old Man Potter in It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), one of the most thoroughly heartless characters in the history of movies. In his own day Barrymore was more closely identified with wise old Dr. Gillespie in MGM’s Dr. Kildare series, and with his annual holiday performances as Ebenezer Scrooge on radio. In fact, Barrymore had been slated to play Scrooge in MGM’s A Christmas Carol (1938) until he broke his hip in an auto accident. That injury landed him in a wheelchair, then advancing arthritis kept him there for the rest of his career — until Down to the Sea in Ships.“He had everything wrong with him, most of it in his head…I said, “You’re not sick, you’re just destroying yourself…I have no sympathy for you. You’re a glutton, you drink too much…You want to destroy yourself, you’re really doing it.”

“We finish the picture, he walked off the set. No wheelchair. No crutches. And he came to me and said, “Mr. Hathaway, I want to tell you, you did more for me and for my life on this picture than ever happened to me before. From my father or my mother, or from anybody. I was just simply sitting there and waiting to die.”

Hathaway went on to say that they remained friends for the rest of Barrymore’s life. In any case, whatever the validity of Hathaway’s recollection, the evidence is there on screen: Barrymore responded — whether out of spite or chagrin — by giving one of his strongest performances in years. For once he’s not merely being wheeled around the set acting crusty (although in his more physically active shots he was often doubled by assistant director Richard Talmadge).

I don’t mean to minimize the genuine pain Barrymore surely suffered, but that wheelchair must have been a real convenience for a man who had never been all that crazy about being an actor to begin with. In youth, his real interests were in painting, writing, and composing music, but the pressure to enter the family trade (and the money to be made from it) kept him on stage, screen and radio for nearly sixty years. The role of Capt. Bering Joy was a recognizable “Lionel Barrymore type”, but it was also a complex and vigorous character betrayed by age and ill health, and Barrymore the self-described ham connected with it on a more profound level than almost any part he ever played. He deserves to be remembered for this performance as much as — indeed, more than — for the unalloyed wickedness of Henry Potter.

Down to the Sea in Ships was Richard Widmark’s fifth movie, after his sensational debut as the giggling psycho killer Tommy Udo in Hathaway’s Kiss of Death (1947). In the intervening three pictures, Widmark played a woman-beating gang lord (The Street with No Name), a murderously jealous bar owner (Road House) and an underhanded western outlaw (Yellow Sky). The studio realized he was in danger of being typecast as a succession of nutjobs, sleazeballs and unsavories (because he played them so well), when what the studio really needed was another leading man. Casting him as Dan Lunceford was a conscious effort to help him segue into more sympathetic roles. It worked. Widmark went on to be one of Fox’s most stalwart leading men, playing good guys (Slattery’s Hurricane, Panic in the Streets), bad guys (No Way Out, O. Henry’s Full House) and guys in between (Pickup on South Street, Don’t Bother to Knock) — until, like many other stars, he went free-agent in the mid-1950s.

Down to the Sea in Ships was Richard Widmark’s fifth movie, after his sensational debut as the giggling psycho killer Tommy Udo in Hathaway’s Kiss of Death (1947). In the intervening three pictures, Widmark played a woman-beating gang lord (The Street with No Name), a murderously jealous bar owner (Road House) and an underhanded western outlaw (Yellow Sky). The studio realized he was in danger of being typecast as a succession of nutjobs, sleazeballs and unsavories (because he played them so well), when what the studio really needed was another leading man. Casting him as Dan Lunceford was a conscious effort to help him segue into more sympathetic roles. It worked. Widmark went on to be one of Fox’s most stalwart leading men, playing good guys (Slattery’s Hurricane, Panic in the Streets), bad guys (No Way Out, O. Henry’s Full House) and guys in between (Pickup on South Street, Don’t Bother to Knock) — until, like many other stars, he went free-agent in the mid-1950s.

In Down to the Sea, Widmark is top-billed, although he doesn’t appear until half an hour in. His Dan Lunceford is the character who goes through the most self-surprising changes in the course of the picture. After all, Jed is an adolescent coming of age, and changes are to be expected, while Capt. Joy, though seemingly set in his ways and defiantly so, proves to be flexible, open to change, and willing to learn — when he thinks nobody is watching and he can do it without losing face.

Capt. Joy blusters, but it’s Dan Lunceford who is most nearly arrogant at the outset; part of the reason the captain scoffs at Lunceford’s education is that he senses Lunceford is more than a little puffed-up about it. For his part, Lunceford treats Capt. Joy with an exaggerated politeness that stops just short of insolent sarcasm. (Capt. Joy: “You may have noticed that most of my crew generally sign on again.” Lunceford [drily]: “Out of affection no doubt, sir.”) His sarcasm towards Jed’s lessons, on the other hand, is undisguised — at first. In time, he comes to realize he has misjudged them both, especially the captain. By the end he’s telling Jed that his grandfather is “more of a man than you or I could ever hope to be.” It’s an admission Lunceford could hardly have imagined making when the voyage began.

And then there’s Dean Stockwell. Stockwell’s first screen role came in 1945, when he was eight years old, and he’s still working today — which means that his career has now lasted longer than Lionel Barrymore’s or Richard Widmark’s. When I screened my print of Down to the Sea in Ships for some friends, one of them said, “Dean Stockwell was a revelation!” She was familiar with Stockwell as an adult actor, and knew he had started as a child star, but had no inkling he was ever as good as he is here. (“He was marvelous,” remembered Hathaway, “just a great actor. Intense little guy.”) My friend was right: Dean Stockwell’s performance here is a revelation, easily (at the age of twelve) the best of his career — and for an actor whose résumé includes Gentleman’s Agreement, The Boy with Green Hair, Compulsion, Long Day’s Journey into Night, Blue Velvet, and the TV series Quantum Leap, that’s saying something. Jed Joy is the fulcrum upon which the plot of Down to the Sea in Ships pivots, and in Stockwell’s performance we see him grow from an uncertain, sometimes petulant child into the makings of a fine, strong young man — he seems even to grow taller as the story progresses (and it’s all in his acting; the shooting schedule wasn’t that protracted).

And then there’s Dean Stockwell. Stockwell’s first screen role came in 1945, when he was eight years old, and he’s still working today — which means that his career has now lasted longer than Lionel Barrymore’s or Richard Widmark’s. When I screened my print of Down to the Sea in Ships for some friends, one of them said, “Dean Stockwell was a revelation!” She was familiar with Stockwell as an adult actor, and knew he had started as a child star, but had no inkling he was ever as good as he is here. (“He was marvelous,” remembered Hathaway, “just a great actor. Intense little guy.”) My friend was right: Dean Stockwell’s performance here is a revelation, easily (at the age of twelve) the best of his career — and for an actor whose résumé includes Gentleman’s Agreement, The Boy with Green Hair, Compulsion, Long Day’s Journey into Night, Blue Velvet, and the TV series Quantum Leap, that’s saying something. Jed Joy is the fulcrum upon which the plot of Down to the Sea in Ships pivots, and in Stockwell’s performance we see him grow from an uncertain, sometimes petulant child into the makings of a fine, strong young man — he seems even to grow taller as the story progresses (and it’s all in his acting; the shooting schedule wasn’t that protracted). I’ve been dancing all around something here, and I might as well come right out and say it: Down to the Sea in Ships is a masterpiece. It’s not one of those “miracle pictures” I’ve talked about before, like Peter Ibbetson or A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Making it was no departure for the Hollywood studio system; on the contrary, pictures like this were right up Hollywood’s alley. If there’s a miracle here, it isn’t that it was made in the first place, but that it turned out so well in the end.

I’ve been dancing all around something here, and I might as well come right out and say it: Down to the Sea in Ships is a masterpiece. It’s not one of those “miracle pictures” I’ve talked about before, like Peter Ibbetson or A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Making it was no departure for the Hollywood studio system; on the contrary, pictures like this were right up Hollywood’s alley. If there’s a miracle here, it isn’t that it was made in the first place, but that it turned out so well in the end.If you ever get the chance to see Down to the Sea in Ships, don’t pass it up. I’ve never shown it to anyone who didn’t love it. I guarantee it: this is one of the greatest movies you never heard of.

_______________

*UPDATE 11/4/2021: Down to the Sea in Ships is now available on DVD from 20th Century Fox Cinema Archives; it’s available here from Amazon.

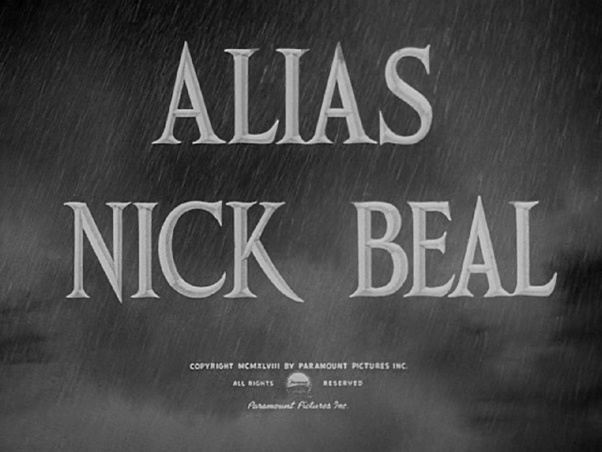

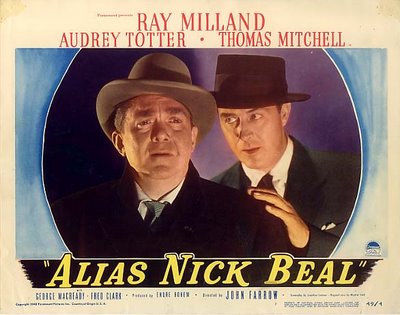

The Paramount mountain dissolves to a slate-colored sky pouring a torrential, whistling rain, riven by claws of lightning and rumbling thunder. There’s a crashing fanfare from composer Franz Waxman that sounds magisterial, commanding and insinuating all at once, then descends into a tortured, frantic violin scherzo. Next the names of the three above-the-title stars — Ray Milland, Audrey Totter, Thomas Mitchell — then the title itself. Alias Nick Beal is under way.

The Paramount mountain dissolves to a slate-colored sky pouring a torrential, whistling rain, riven by claws of lightning and rumbling thunder. There’s a crashing fanfare from composer Franz Waxman that sounds magisterial, commanding and insinuating all at once, then descends into a tortured, frantic violin scherzo. Next the names of the three above-the-title stars — Ray Milland, Audrey Totter, Thomas Mitchell — then the title itself. Alias Nick Beal is under way.

That’s when Foster receives a cryptic summons to a dingy dive down by the waterfront: “If you want to nail Hanson, drop around the China Coast at eight tonight.” The man he meets that night (Ray Milland) is clean-shaven and dapper, impeccably groomed and dressed, cutting a figure entirely at odds with the squalid little tavern where Foster finds him. His card reads simply: “Nicholas Beal, Agent”. “Agent for what?” asks Foster. Beal grins slightly. “That depends. Possibly for you.”

That’s when Foster receives a cryptic summons to a dingy dive down by the waterfront: “If you want to nail Hanson, drop around the China Coast at eight tonight.” The man he meets that night (Ray Milland) is clean-shaven and dapper, impeccably groomed and dressed, cutting a figure entirely at odds with the squalid little tavern where Foster finds him. His card reads simply: “Nicholas Beal, Agent”. “Agent for what?” asks Foster. Beal grins slightly. “That depends. Possibly for you.” Foster decides. He tucks the books under his arm, puts out the light, and makes his way out of the cannery by the beam of a flashlight Beal left behind. In the pitch dark of the outer room, his light startles a rat on a shelf. The rat squeaks plaintively and stares at Foster, eye to eye. We can almost read the rat’s mind, as clearly as if he were speaking: Welcome to my world.

Foster decides. He tucks the books under his arm, puts out the light, and makes his way out of the cannery by the beam of a flashlight Beal left behind. In the pitch dark of the outer room, his light startles a rat on a shelf. The rat squeaks plaintively and stares at Foster, eye to eye. We can almost read the rat’s mind, as clearly as if he were speaking: Welcome to my world.

Naturally, the mainspring of Alias Nick Beal must be Ray Milland’s performance, and he’s nothing short of superb. His Beal is smooth, quiet, confident, glib. Nothing ruffles him. But don’t try to touch him. “I don’t like to be touched.” He says it simply, almost apologetic, but his meaning is clear: you won’t like what happens when you do something Nick Beal doesn’t like. When Beal once flares in anger, it’s over in an instant and his calm demeanor returns, but the moment is unnerving; though his eyes are angry slits in that moment, we can almost see the fires of Hell banked behind them.

Naturally, the mainspring of Alias Nick Beal must be Ray Milland’s performance, and he’s nothing short of superb. His Beal is smooth, quiet, confident, glib. Nothing ruffles him. But don’t try to touch him. “I don’t like to be touched.” He says it simply, almost apologetic, but his meaning is clear: you won’t like what happens when you do something Nick Beal doesn’t like. When Beal once flares in anger, it’s over in an instant and his calm demeanor returns, but the moment is unnerving; though his eyes are angry slits in that moment, we can almost see the fires of Hell banked behind them.

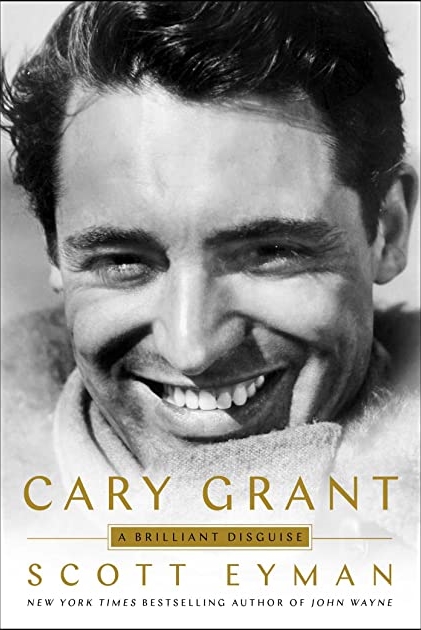

At Cinevent 50 in Columbus, Ohio in 2018, there was a moderated Saturday-afternoon discussion between historians Leonard Maltin and Scott Eyman. At one point, Leonard said of Scott:

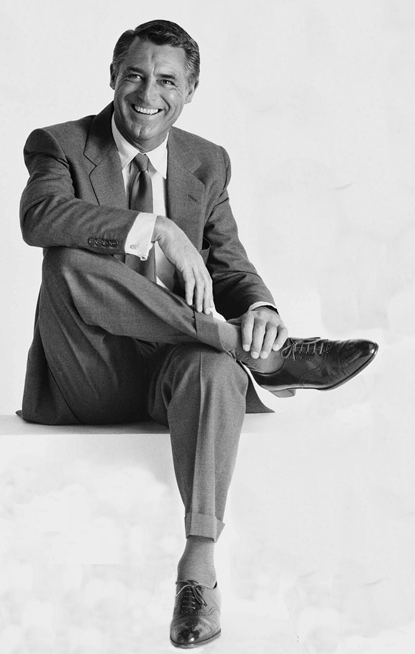

At Cinevent 50 in Columbus, Ohio in 2018, there was a moderated Saturday-afternoon discussion between historians Leonard Maltin and Scott Eyman. At one point, Leonard said of Scott: For Archie Leach, the Cary Grant persona was, in Scott’s apt phrase, a brilliant disguise — but it was also a precarious balancing act. Somehow, through some alchemical mix of talent, timing, ambition and luck, this music hall acrobat from Bristol crafted a personality unlike any other. The only child of a feckless alcoholic father and an emotionally unstable mother (young Archie’s father committed her to a mental hospital and told the boy she had died; he didn’t learn the truth for over 20 years), Archie Leach managed to remodel himself into the epitome of urbane sophistication and the greatest romantic comedian in the history of the acting profession.

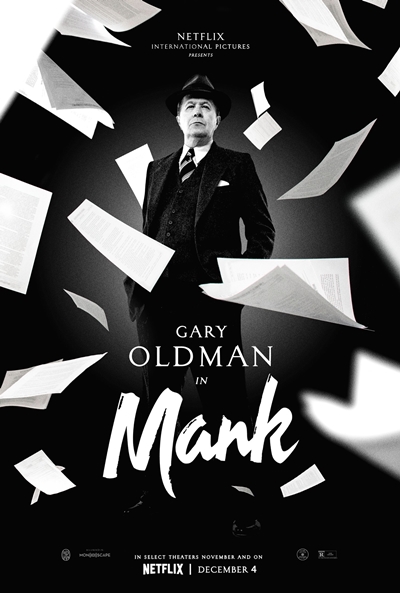

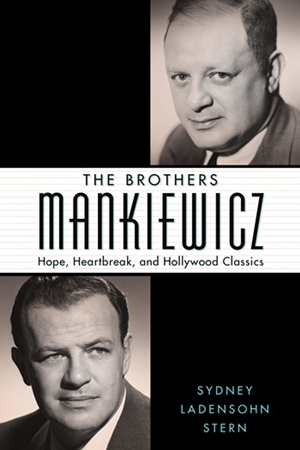

For Archie Leach, the Cary Grant persona was, in Scott’s apt phrase, a brilliant disguise — but it was also a precarious balancing act. Somehow, through some alchemical mix of talent, timing, ambition and luck, this music hall acrobat from Bristol crafted a personality unlike any other. The only child of a feckless alcoholic father and an emotionally unstable mother (young Archie’s father committed her to a mental hospital and told the boy she had died; he didn’t learn the truth for over 20 years), Archie Leach managed to remodel himself into the epitome of urbane sophistication and the greatest romantic comedian in the history of the acting profession.  Well, that was then, this is now, and I’m breaking that rule again to discuss another contemporary movie and another long shadow. The movie is Mank, directed by David Fincher from a script by his father Jack, and the shadow belongs to Citizen Kane (1941). The younger Fincher appears to have undertaken Mank as a tribute to his father, who died in 2003 (the movie is dedicated to his memory). Besides that, it fits into the intermittent vogue for making movies about the making of movies — that is, about the making of specific movies. It’s a sub-genre that dates back at least as far as 1980’s TV movie The Scarlett O’Hara War, in which 55-year-old Tony Curtis played the 35-year-old David O. Selznick beating the bushes to find a leading lady for Gone With the Wind. The vogue has cropped up from time to time ever since; examples include the aforementioned Saving Mr. Banks and 2012’s Hitchcock, about the making of Psycho. Even Citizen Kane‘s production has been done before, in RKO 281 (1999), with Liev Schreiber as Orson Welles and James Cromwell as William Randolph Hearst.

Well, that was then, this is now, and I’m breaking that rule again to discuss another contemporary movie and another long shadow. The movie is Mank, directed by David Fincher from a script by his father Jack, and the shadow belongs to Citizen Kane (1941). The younger Fincher appears to have undertaken Mank as a tribute to his father, who died in 2003 (the movie is dedicated to his memory). Besides that, it fits into the intermittent vogue for making movies about the making of movies — that is, about the making of specific movies. It’s a sub-genre that dates back at least as far as 1980’s TV movie The Scarlett O’Hara War, in which 55-year-old Tony Curtis played the 35-year-old David O. Selznick beating the bushes to find a leading lady for Gone With the Wind. The vogue has cropped up from time to time ever since; examples include the aforementioned Saving Mr. Banks and 2012’s Hitchcock, about the making of Psycho. Even Citizen Kane‘s production has been done before, in RKO 281 (1999), with Liev Schreiber as Orson Welles and James Cromwell as William Randolph Hearst.

Marion Davies went to her grave insisting that she never saw Citizen Kane, and while I’m not sure I believe that, it was her story and she stuck to it to the end. In any case, the idea that she would have driven out to Victorville to sit on the porch critiquing the fine points of Mankiewicz’s script before shooting even started is just plain stupid.

Marion Davies went to her grave insisting that she never saw Citizen Kane, and while I’m not sure I believe that, it was her story and she stuck to it to the end. In any case, the idea that she would have driven out to Victorville to sit on the porch critiquing the fine points of Mankiewicz’s script before shooting even started is just plain stupid. There’s hardly a detail too minor for the movie to go out of its way to get wrong. Herman Mankiewicz had a mustache in 1940. Marion Davies was sweet and well-loved, but she drank too much and, having retired from the screen in 1937, she was puffy and tending to overweight by 1939; also, she stuttered. As for Rita Alexander, no Englishwoman then, or Englishman either, would have used the word “shitty” in mixed company, even if they did think aircraft carriers were “a shitty idea” (which nobody did). That word was a pure Americanism – and for that matter, even in America few women would have said it in those days. The road accident that broke Mankiewicz’s leg happened not because a letter fluttered out of his convertible with the top down, but because Tommy Phipps, who was driving, lost control of the car in the rain on Route 66. The Mankiewicz brothers never called each other “Hermie” and “Joey”, and nobody on Planet Earth was dumb enough to call William Randolph Hearst “Willie”, even behind his back in a soundproof room.

There’s hardly a detail too minor for the movie to go out of its way to get wrong. Herman Mankiewicz had a mustache in 1940. Marion Davies was sweet and well-loved, but she drank too much and, having retired from the screen in 1937, she was puffy and tending to overweight by 1939; also, she stuttered. As for Rita Alexander, no Englishwoman then, or Englishman either, would have used the word “shitty” in mixed company, even if they did think aircraft carriers were “a shitty idea” (which nobody did). That word was a pure Americanism – and for that matter, even in America few women would have said it in those days. The road accident that broke Mankiewicz’s leg happened not because a letter fluttered out of his convertible with the top down, but because Tommy Phipps, who was driving, lost control of the car in the rain on Route 66. The Mankiewicz brothers never called each other “Hermie” and “Joey”, and nobody on Planet Earth was dumb enough to call William Randolph Hearst “Willie”, even behind his back in a soundproof room. Late in the movie, I think at the climax (such as it was), there was a long scene in the “Refectory” at San Simeon (although in Messerschmidt’s hands it just looked like a rather well-furnished cave). The scene seemed to be terribly important; anyhow, it had Gary Oldman going tooth-and-nail for his second Oscar. But by that time the movie had completely lost me and I was no longer even pretending to pay attention; I just sat there rolling my eyes and making that wrist-rotating gesture that is the universal signal for let’s-wind-this-thing-up-already. (I couldn’t help remembering something Pauline Kael wrote in one of her reviews: “Sitting in the darkened theater, I kept listening for snorts, but every time I heard one I could feel the breath on my hands.”) Somewhere in this seemingly-terribly-important scene, Mankiewicz puked and made his famous wisecrack about the white wine coming up with the fish (which actually happened at the home of Arthur Hornblow Jr.), but that’s really all I remember. I was just marking time, waiting for this ridiculous, fraudulent movie to be over. And then…finally…it was.

Late in the movie, I think at the climax (such as it was), there was a long scene in the “Refectory” at San Simeon (although in Messerschmidt’s hands it just looked like a rather well-furnished cave). The scene seemed to be terribly important; anyhow, it had Gary Oldman going tooth-and-nail for his second Oscar. But by that time the movie had completely lost me and I was no longer even pretending to pay attention; I just sat there rolling my eyes and making that wrist-rotating gesture that is the universal signal for let’s-wind-this-thing-up-already. (I couldn’t help remembering something Pauline Kael wrote in one of her reviews: “Sitting in the darkened theater, I kept listening for snorts, but every time I heard one I could feel the breath on my hands.”) Somewhere in this seemingly-terribly-important scene, Mankiewicz puked and made his famous wisecrack about the white wine coming up with the fish (which actually happened at the home of Arthur Hornblow Jr.), but that’s really all I remember. I was just marking time, waiting for this ridiculous, fraudulent movie to be over. And then…finally…it was.

A precocious student with an artistic bent, Olivia caught the acting bug as a teenager, making her debut at 16 playing Lewis Carroll’s Alice for the Saratoga Community Players. Her stepfather, a real petty tyrant, disapproved, and he tried putting his foot down after she was cast in a school production of Pride and Prejudice. None of this acting nonsense, he decreed, not if she wanted to live under his roof — only to learn the lesson others would learn when they tried pushing Olivia de Havilland around: She moved in with a family friend, and the show (and Olivia) went on.

A precocious student with an artistic bent, Olivia caught the acting bug as a teenager, making her debut at 16 playing Lewis Carroll’s Alice for the Saratoga Community Players. Her stepfather, a real petty tyrant, disapproved, and he tried putting his foot down after she was cast in a school production of Pride and Prejudice. None of this acting nonsense, he decreed, not if she wanted to live under his roof — only to learn the lesson others would learn when they tried pushing Olivia de Havilland around: She moved in with a family friend, and the show (and Olivia) went on.

Now before we go on, let’s pause to consider how Captain Blood might have turned out with Robert Donat and Marion Davies. Fortunately, we were spared that. Instead of Donat and Davies, we got Captain Blood with Errol and Olivia, and it made stars of them both. In eight pictures together, they shared a reserved grace that provided a good complement each for the other. Not to mention an erotic chemistry so strong that in those few pictures where their characters don’t end up together — like The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936) and Four’s a Crowd (1938) — something seems distinctly out of whack.

Now before we go on, let’s pause to consider how Captain Blood might have turned out with Robert Donat and Marion Davies. Fortunately, we were spared that. Instead of Donat and Davies, we got Captain Blood with Errol and Olivia, and it made stars of them both. In eight pictures together, they shared a reserved grace that provided a good complement each for the other. Not to mention an erotic chemistry so strong that in those few pictures where their characters don’t end up together — like The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936) and Four’s a Crowd (1938) — something seems distinctly out of whack.

Over the years the sisters — protesting a bit too much, perhaps — would sometimes pose for photos to show that things were just fine between them. They were always burying the hatchet, and always remembering where they left it. The “final schism”, as Joan phrased it, seems to have come with their mother’s terminal illness in 1975. Joan, on tour in Cactus Flower, felt slighted at being excluded from end-of-life treatment decisions; worse, she felt Olivia was dilatory in letting her know when the end was near, so she was still on the road when Mummy breathed her last. At the memorial service, Joan refused to speak to her older sister. Three years later, in her autobiography, Joan, like a volcano that would not stop, spewed sixty years’ worth of pent-up hostility — prompted, perhaps, by still-tender wounds about their mother. In an interview promoting the book she said, “You can divorce your sister as well as your husbands. I don’t see her and I don’t intend to.” In public, Olivia maintained a lofty silence; privately she took to calling Joan the Dragon Lady. Joan titled her memoir No Bed of Roses. Olivia dubbed it No Shred of Truth.

Over the years the sisters — protesting a bit too much, perhaps — would sometimes pose for photos to show that things were just fine between them. They were always burying the hatchet, and always remembering where they left it. The “final schism”, as Joan phrased it, seems to have come with their mother’s terminal illness in 1975. Joan, on tour in Cactus Flower, felt slighted at being excluded from end-of-life treatment decisions; worse, she felt Olivia was dilatory in letting her know when the end was near, so she was still on the road when Mummy breathed her last. At the memorial service, Joan refused to speak to her older sister. Three years later, in her autobiography, Joan, like a volcano that would not stop, spewed sixty years’ worth of pent-up hostility — prompted, perhaps, by still-tender wounds about their mother. In an interview promoting the book she said, “You can divorce your sister as well as your husbands. I don’t see her and I don’t intend to.” In public, Olivia maintained a lofty silence; privately she took to calling Joan the Dragon Lady. Joan titled her memoir No Bed of Roses. Olivia dubbed it No Shred of Truth.  Olivia eventually got her own Oscar, of course. Two of them, in fact, and both at Paramount, the studio that had borrowed her for Hold Back the Dawn. First, in 1946, came To Each His Own. Olivia played an unwed mother who, when her lover is killed in World War I, is forced to give up her baby to be adopted by an old frenemy, then to watch from afar as the boy grows up, thinking of her only as a fussy and rather pathetic family friend. It was, in Oscar historian Robert Osborne’s apt phrase, “a Tiffany tear-jerker”. In the movie’s final scene, when the boy, now grown to manhood, finally gets it through his head why “Aunt Jody” has always been so nice to him, and says to her, “May I have this dance…Mother?” — the look on Olivia’s face is enough to reduce a bronze statue to helpless sobs.

Olivia eventually got her own Oscar, of course. Two of them, in fact, and both at Paramount, the studio that had borrowed her for Hold Back the Dawn. First, in 1946, came To Each His Own. Olivia played an unwed mother who, when her lover is killed in World War I, is forced to give up her baby to be adopted by an old frenemy, then to watch from afar as the boy grows up, thinking of her only as a fussy and rather pathetic family friend. It was, in Oscar historian Robert Osborne’s apt phrase, “a Tiffany tear-jerker”. In the movie’s final scene, when the boy, now grown to manhood, finally gets it through his head why “Aunt Jody” has always been so nice to him, and says to her, “May I have this dance…Mother?” — the look on Olivia’s face is enough to reduce a bronze statue to helpless sobs. Also at 100, she showed the world that there was litigation in the old girl yet. She sued FX Networks and producer Ryan Murphy over Feud: Bette and Joan, an eight-part miniseries that purported to dish the dirt on the making of What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? in 1962 and the diva-rivalry between Bette Davis and Joan Crawford. Olivia had been a good friend of Bette’s, and she replaced Joan when she was fired from her and Bette’s follow-up teaming on Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964), so Olivia was represented as a supporting character in the miniseries, and played by Catherine Zeta-Jones. As these two pictures suggest, neither Ms. Zeta-Jones, her costumer, nor her hairdresser gave much evidence of ever having seen or heard of Olivia. Neither did any of the writers, and that’s what she sued over, charging that her privacy had been invaded without her permission or input, that she had been slandered and misrepresented. True enough; Feud was sleazy stuff, despite all the A-list names, and it misrepresented pretty much everybody it mentioned. The only reason Olivia was the only plaintiff in the case is that she was the only one who was still alive.

Also at 100, she showed the world that there was litigation in the old girl yet. She sued FX Networks and producer Ryan Murphy over Feud: Bette and Joan, an eight-part miniseries that purported to dish the dirt on the making of What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? in 1962 and the diva-rivalry between Bette Davis and Joan Crawford. Olivia had been a good friend of Bette’s, and she replaced Joan when she was fired from her and Bette’s follow-up teaming on Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964), so Olivia was represented as a supporting character in the miniseries, and played by Catherine Zeta-Jones. As these two pictures suggest, neither Ms. Zeta-Jones, her costumer, nor her hairdresser gave much evidence of ever having seen or heard of Olivia. Neither did any of the writers, and that’s what she sued over, charging that her privacy had been invaded without her permission or input, that she had been slandered and misrepresented. True enough; Feud was sleazy stuff, despite all the A-list names, and it misrepresented pretty much everybody it mentioned. The only reason Olivia was the only plaintiff in the case is that she was the only one who was still alive.

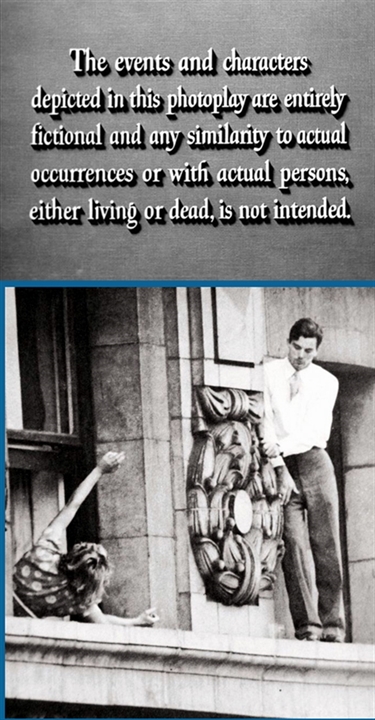

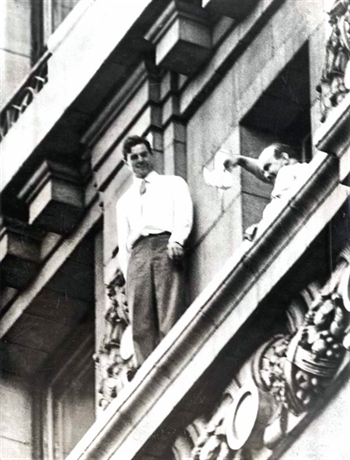

This title card appears early in Henry Hathaway’s Fourteen Hours — at the “climax” of the opening credits, you might say, just before the credit cards for producer Sol C. Siegel and director Hathaway. It’s the standard “entirely fictional and any similarity” disclaimer, the kind that usually appears in super-small type somewhere near the copyright notice, the MPAA “approved” certificate number, the Western Electric and IATSE credits, and other things that are legally required but nobody really cares if you see or not. For this picture, though, 20th Century Fox took the unusual step of making sure the disclaimer was very prominently placed where even the most inattentive could hardly miss it.

This title card appears early in Henry Hathaway’s Fourteen Hours — at the “climax” of the opening credits, you might say, just before the credit cards for producer Sol C. Siegel and director Hathaway. It’s the standard “entirely fictional and any similarity” disclaimer, the kind that usually appears in super-small type somewhere near the copyright notice, the MPAA “approved” certificate number, the Western Electric and IATSE credits, and other things that are legally required but nobody really cares if you see or not. For this picture, though, 20th Century Fox took the unusual step of making sure the disclaimer was very prominently placed where even the most inattentive could hardly miss it.

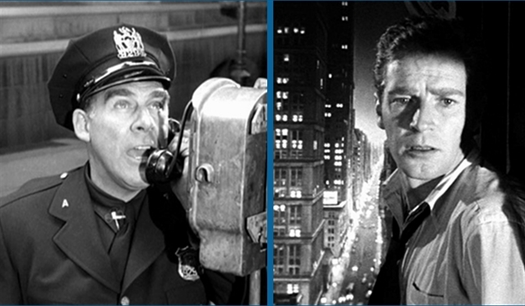

The picture opens quietly — in silence, in fact, without dialogue or even background music. (Indeed, except for Alfred Newman’s fervid theme under the opening credits, then a second theme swelling through the movie’s last 90 seconds, there’s no music in the entire picture.) We are introduced to what will prove to be the two central characters in the drama that follows. First we see Patrolman Charlie Dunnigan (Paul Douglas as the movie’s version of Charles Glasco) walking his beat in the early morning calm. He passes the Rodney Hotel, where a worker is polishing the brass plate at the entrance. Meanwhile, up in Room 1505…

The picture opens quietly — in silence, in fact, without dialogue or even background music. (Indeed, except for Alfred Newman’s fervid theme under the opening credits, then a second theme swelling through the movie’s last 90 seconds, there’s no music in the entire picture.) We are introduced to what will prove to be the two central characters in the drama that follows. First we see Patrolman Charlie Dunnigan (Paul Douglas as the movie’s version of Charles Glasco) walking his beat in the early morning calm. He passes the Rodney Hotel, where a worker is polishing the brass plate at the entrance. Meanwhile, up in Room 1505…

Then the silence is rudely broken by the first human sound we hear — a secretary screaming in the window of a bank building across the street. Dunnigan dashes into the hotel to alert the staff, while the waiter calls down to the switchboard for the same reason. Dunnigan and Harris, the assistant manager (Willard Waterman), knowing now which room to go to, head up in the elevator. In the room, Harris blusters at Robert to come inside, sounding like an impotent scold.

Then the silence is rudely broken by the first human sound we hear — a secretary screaming in the window of a bank building across the street. Dunnigan dashes into the hotel to alert the staff, while the waiter calls down to the switchboard for the same reason. Dunnigan and Harris, the assistant manager (Willard Waterman), knowing now which room to go to, head up in the elevator. In the room, Harris blusters at Robert to come inside, sounding like an impotent scold.  The colloquy between Charlie Dunnigan and Robert Cosick, a mixture of urgent pleading and forced-casual chitchat, provides the spine of Fourteen Hours, just as the real one between Charles Glasco and John Warde did for Joel Sayre’s New Yorker article. (Notice too how Joe MacDonald’s deep-focus photography emphasizes both men’s perilous perch 15 stories up. MacDonald was a master cinematographer who worked with Hathaway on nine pictures, including some of his best.)

The colloquy between Charlie Dunnigan and Robert Cosick, a mixture of urgent pleading and forced-casual chitchat, provides the spine of Fourteen Hours, just as the real one between Charles Glasco and John Warde did for Joel Sayre’s New Yorker article. (Notice too how Joe MacDonald’s deep-focus photography emphasizes both men’s perilous perch 15 stories up. MacDonald was a master cinematographer who worked with Hathaway on nine pictures, including some of his best.)  Over this bare factual skeleton Paxton’s script skillfully weaves a variety of fictional stories among the people drawn for one reason or another to the Rodney Hotel and the street outside. It amounts to a cross-section of the New York public circa 1950 — and for all the changes the city has seen in 69 years, it still rings true today.

Over this bare factual skeleton Paxton’s script skillfully weaves a variety of fictional stories among the people drawn for one reason or another to the Rodney Hotel and the street outside. It amounts to a cross-section of the New York public circa 1950 — and for all the changes the city has seen in 69 years, it still rings true today. Elsewhere in the crowd the reaction is more compassionate. Two young office workers, Ruth (Debra Paget, left) and Barbara (Joyce Van Patten, right), have gotten sidetracked on their way to work. The fretful Barbara wants only to get to work before they get in trouble with the boss. But Ruth is more worried about the stranger on the fifteenth floor: How old is he? What kind of trouble is he in? “Maybe someone was cruel to him, or maybe he’s just lonely…I wish I could help him.” Her tender words catch the ear of Danny behind her (Jeffrey Hunter), also pausing on his way to work. When Barbara gives up and leaves, Danny and Ruth strike up a sweetly tentative conversation. As the day wears on, neither of them will get to work. Feelings grow between them, and Danny reflects on how they might have gone their whole lives, missing each other by minutes, if it hadn’t been for this day. Hunter and the 17-year-old Paget were already launched on their successful careers as Fox contract players. Van Patten, making her film debut at 16, would in time become one of television’s busiest character actresses in a career that is still going strong today.

Elsewhere in the crowd the reaction is more compassionate. Two young office workers, Ruth (Debra Paget, left) and Barbara (Joyce Van Patten, right), have gotten sidetracked on their way to work. The fretful Barbara wants only to get to work before they get in trouble with the boss. But Ruth is more worried about the stranger on the fifteenth floor: How old is he? What kind of trouble is he in? “Maybe someone was cruel to him, or maybe he’s just lonely…I wish I could help him.” Her tender words catch the ear of Danny behind her (Jeffrey Hunter), also pausing on his way to work. When Barbara gives up and leaves, Danny and Ruth strike up a sweetly tentative conversation. As the day wears on, neither of them will get to work. Feelings grow between them, and Danny reflects on how they might have gone their whole lives, missing each other by minutes, if it hadn’t been for this day. Hunter and the 17-year-old Paget were already launched on their successful careers as Fox contract players. Van Patten, making her film debut at 16, would in time become one of television’s busiest character actresses in a career that is still going strong today. Needless to say, New York’s newshounds are also Johnny-on-the-spot. Newspapermen swarm over the scene like ants on a sugar cube. New York announcer George Putnam, playing himself, gives a play-by-play summary from a radio truck in the street. Another radio reporter barges into Room 1505 to jam a microphone out the window to eavesdrop on Dunnigan and Robert’s conversation — only to get the bum’s rush from the vigilant police. Station WNBC dispatches a television camera crew to the roof of a building across the street from the hotel. (Curiously enough, this wasn’t just an embellishment in Paxton’s script. NBC really did broadcast TV coverage of John Warde’s exploit back in 1938, even though there probably weren’t more than a few dozen sets in the whole city, and practically none in the rest of the country. It may well have been the very first example of television covering a breaking news story.)

Needless to say, New York’s newshounds are also Johnny-on-the-spot. Newspapermen swarm over the scene like ants on a sugar cube. New York announcer George Putnam, playing himself, gives a play-by-play summary from a radio truck in the street. Another radio reporter barges into Room 1505 to jam a microphone out the window to eavesdrop on Dunnigan and Robert’s conversation — only to get the bum’s rush from the vigilant police. Station WNBC dispatches a television camera crew to the roof of a building across the street from the hotel. (Curiously enough, this wasn’t just an embellishment in Paxton’s script. NBC really did broadcast TV coverage of John Warde’s exploit back in 1938, even though there probably weren’t more than a few dozen sets in the whole city, and practically none in the rest of the country. It may well have been the very first example of television covering a breaking news story.)

While the crowd in the street mills about gawking, wringing their hands, or cracking callous jokes, up on the fifteenth floor things are in a muffled uproar. The NYPD’s rescue efforts are commanded by the officious but efficient Deputy Chief Moksar (Howard Da Silva, left), who coordinates activities while straight-arming a swarm of reporters and dealing with other interfering looky-loos (at one excruciatingly delicate moment, a crackpot preacher bursts into the room bellowing at Robert to kneel and pray). Police psychiatrist Dr. Strauss (Martin Gabel, center) offers on-the-fly advice to Moksar and Dunnigan on Robert’s mental state. Further complications come with the arrival of Robert’s divorced parents — his clutching, hysterical mother (Agnes Moorehead, second right) and feckless alcoholic father (Robert Keith, right), who graphically illustrate the Cosick family dysfunction. (“No wonder he’s cuckoo!” growls Moksar.)

While the crowd in the street mills about gawking, wringing their hands, or cracking callous jokes, up on the fifteenth floor things are in a muffled uproar. The NYPD’s rescue efforts are commanded by the officious but efficient Deputy Chief Moksar (Howard Da Silva, left), who coordinates activities while straight-arming a swarm of reporters and dealing with other interfering looky-loos (at one excruciatingly delicate moment, a crackpot preacher bursts into the room bellowing at Robert to kneel and pray). Police psychiatrist Dr. Strauss (Martin Gabel, center) offers on-the-fly advice to Moksar and Dunnigan on Robert’s mental state. Further complications come with the arrival of Robert’s divorced parents — his clutching, hysterical mother (Agnes Moorehead, second right) and feckless alcoholic father (Robert Keith, right), who graphically illustrate the Cosick family dysfunction. (“No wonder he’s cuckoo!” growls Moksar.)

Fourteen Hours was what was known as an A-minus picture — that is, a picture with an A budget but no major stars. The closest thing to one was Paul Douglas, the former sports announcer who had been one of Fox’s most popular and reliable supporting actors since his breakout work as Linda Darnell’s husband in A Letter to Three Wives (’49). In 1950 as Fourteen Hours went into production he was teetering between first and second leads, which he would continue to do for the rest of his life, until his untimely death from a heart attack in 1959 at 52. In Fourteen Hours, top-billed in a first-rate ensemble cast, he carries much of the film as his Charlie Dunnigan tries to lure Robert Cosick literally back from the brink, winging it from moment to moment with a seat-of-the-pants common sense.

Fourteen Hours was what was known as an A-minus picture — that is, a picture with an A budget but no major stars. The closest thing to one was Paul Douglas, the former sports announcer who had been one of Fox’s most popular and reliable supporting actors since his breakout work as Linda Darnell’s husband in A Letter to Three Wives (’49). In 1950 as Fourteen Hours went into production he was teetering between first and second leads, which he would continue to do for the rest of his life, until his untimely death from a heart attack in 1959 at 52. In Fourteen Hours, top-billed in a first-rate ensemble cast, he carries much of the film as his Charlie Dunnigan tries to lure Robert Cosick literally back from the brink, winging it from moment to moment with a seat-of-the-pants common sense. At the end of Fourteen Hours Robert Cosick is finally brought in through the window to safety — you’ll have to see the movie to find out exactly how that comes about. Unfortunately, the day didn’t end as happily for John William Warde. At 10:30 p.m. that night, John said to Officer Glasco, “I’ve made up my mind.” Glasco took this as an optimistic sign that John had decided to come in; at least that’s how he chose to read it. “That’s the way to talk,” he said. About that time, a childhood friend of John’s arrived in room 1714, and he relieved Glasco at the window talking to John.

At the end of Fourteen Hours Robert Cosick is finally brought in through the window to safety — you’ll have to see the movie to find out exactly how that comes about. Unfortunately, the day didn’t end as happily for John William Warde. At 10:30 p.m. that night, John said to Officer Glasco, “I’ve made up my mind.” Glasco took this as an optimistic sign that John had decided to come in; at least that’s how he chose to read it. “That’s the way to talk,” he said. About that time, a childhood friend of John’s arrived in room 1714, and he relieved Glasco at the window talking to John.

Sunday morning began with another George O’Brien B-picture directed by David Howard.

Sunday morning began with another George O’Brien B-picture directed by David Howard.  Next came

Next came  After the final three chapters of Hawk of the Wilderness came

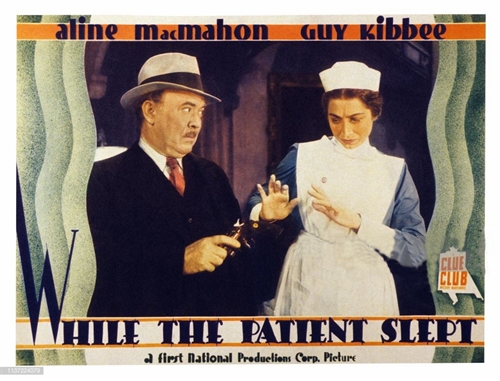

After the final three chapters of Hawk of the Wilderness came  This brought us at last to the final picture of the weekend, a nifty little 65-minute murder mystery,

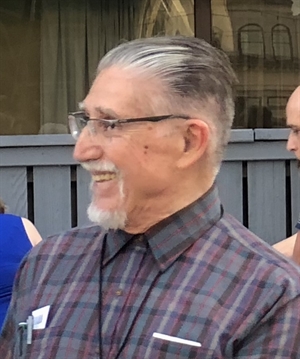

This brought us at last to the final picture of the weekend, a nifty little 65-minute murder mystery,  I don’t want to leave my survey of this year’s Cinevent without mentioning my friend Phil Capasso. Last year, at the Golden Anniversary Celebration, Phil was honored as the only person who had been to every single Cinevent since the first one back in 1969. This dedicated attendance earned him the first slice of the 50th anniversary cake that evening, not to mention the privilege of introducing Cinevent 50’s guest of honor Leonard Maltin. Needless to say, Phil was in Seventh Heaven at that party, and as happy as I’d ever seen him. Then on August 28, 2018, barely three months after I took this picture of him in Columbus, Phil passed away at his home in Carmel, Indiana, at age 82. I’m sure he was planning for his annual trek to Los Angeles for Cinecon 54 on Labor Day Weekend. And I have no doubt he was already looking forward (in his customary phrase, “if God spares”) to joining us all again in Columbus for this year’s Cinevent 51.

I don’t want to leave my survey of this year’s Cinevent without mentioning my friend Phil Capasso. Last year, at the Golden Anniversary Celebration, Phil was honored as the only person who had been to every single Cinevent since the first one back in 1969. This dedicated attendance earned him the first slice of the 50th anniversary cake that evening, not to mention the privilege of introducing Cinevent 50’s guest of honor Leonard Maltin. Needless to say, Phil was in Seventh Heaven at that party, and as happy as I’d ever seen him. Then on August 28, 2018, barely three months after I took this picture of him in Columbus, Phil passed away at his home in Carmel, Indiana, at age 82. I’m sure he was planning for his annual trek to Los Angeles for Cinecon 54 on Labor Day Weekend. And I have no doubt he was already looking forward (in his customary phrase, “if God spares”) to joining us all again in Columbus for this year’s Cinevent 51. Saturday’s

Saturday’s  After the cartoons — just like a Saturday Kiddie Matinee of my childhood — it was three more chapters of Hawk of the Wilderness. Then the Saturday Matinee mold was broken by a silent feature,

After the cartoons — just like a Saturday Kiddie Matinee of my childhood — it was three more chapters of Hawk of the Wilderness. Then the Saturday Matinee mold was broken by a silent feature,  After lunch it was the return of a longtime favorite feature at Cinevent, a program of Charley Chase comedy shorts. This year’s entries were

After lunch it was the return of a longtime favorite feature at Cinevent, a program of Charley Chase comedy shorts. This year’s entries were  Just before the dinner break came one of the surprise highlights of the whole weekend — a surprise to me, anyhow. Not because I didn’t expect it to be good, but because it was so much better than I expected. This was

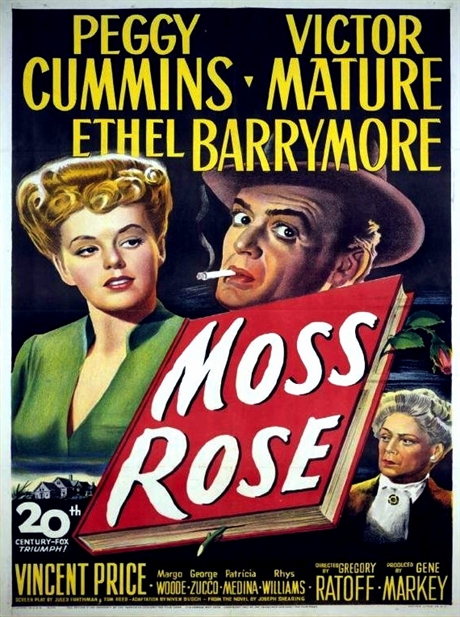

Just before the dinner break came one of the surprise highlights of the whole weekend — a surprise to me, anyhow. Not because I didn’t expect it to be good, but because it was so much better than I expected. This was  Richard Barrios introduced

Richard Barrios introduced  Moss Rose (1947)

Moss Rose (1947) There was some important news announced on Saturday by Cinevent chair Michael Haynes (on the left in this picture, in case you need to be told) and Dealers’ Room coordinator Samantha Glasser (the one who isn’t Michael).

There was some important news announced on Saturday by Cinevent chair Michael Haynes (on the left in this picture, in case you need to be told) and Dealers’ Room coordinator Samantha Glasser (the one who isn’t Michael). Friday morning at Cinevent started off bright and early with one of the last of 20th Century Fox’s fanciful biopics of figures from the Golden Age of Vaudeville. Earlier years had seen highly fictionalized treatments of the lives of Lillian Russell (1940), songwriter Paul Dresser (My Gal Sal, 1942), The Dolly Sisters (1945), another songwriter, Joe Howard (I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now, 1947), Florodora girl Myrtle McKinley (Mother Wore Tights, 1947), Lotta Crabtree (Golden Girl, 1951) and even John Philip Sousa (Stars and Stripes Forever, 1952). Today’s specimen of the sub-genre was

Friday morning at Cinevent started off bright and early with one of the last of 20th Century Fox’s fanciful biopics of figures from the Golden Age of Vaudeville. Earlier years had seen highly fictionalized treatments of the lives of Lillian Russell (1940), songwriter Paul Dresser (My Gal Sal, 1942), The Dolly Sisters (1945), another songwriter, Joe Howard (I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now, 1947), Florodora girl Myrtle McKinley (Mother Wore Tights, 1947), Lotta Crabtree (Golden Girl, 1951) and even John Philip Sousa (Stars and Stripes Forever, 1952). Today’s specimen of the sub-genre was  Not that it would have been easy. The Production Code was still in firm control, and Eva Tanguay’s main selling point was blatantly sexual, a lusty throwing off of the prim strictures of Victorian ladyhood (Rosen says that her dances frequently looked like simulated orgasms), where Cohan’s chief selling point was patriotism, much easier to get through the Breen Office (especially during a war). But it could have been done — just not with Bullock’s script. And, alas, even with a better script, probably not with Mitzi Gaynor either. Gaynor may well have had more talent that Tanguay, but probably not half the personality. Mitzi was basically a pretty-good chorus girl who got some fantastic breaks — sort of a Vera-Ellen, but able to do her own singing.

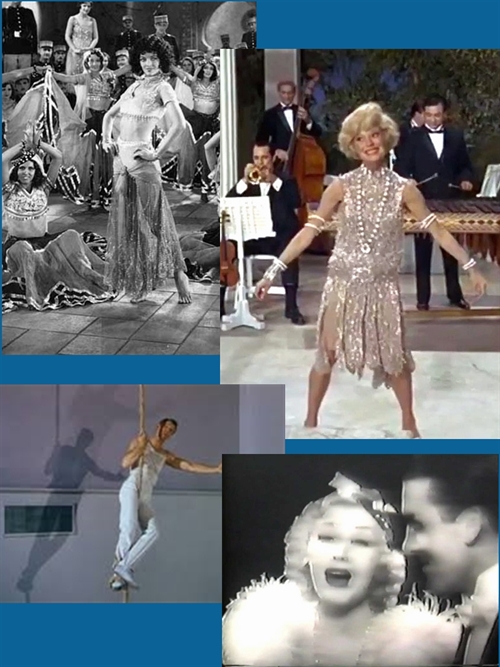

Not that it would have been easy. The Production Code was still in firm control, and Eva Tanguay’s main selling point was blatantly sexual, a lusty throwing off of the prim strictures of Victorian ladyhood (Rosen says that her dances frequently looked like simulated orgasms), where Cohan’s chief selling point was patriotism, much easier to get through the Breen Office (especially during a war). But it could have been done — just not with Bullock’s script. And, alas, even with a better script, probably not with Mitzi Gaynor either. Gaynor may well have had more talent that Tanguay, but probably not half the personality. Mitzi was basically a pretty-good chorus girl who got some fantastic breaks — sort of a Vera-Ellen, but able to do her own singing. Which brings us to the movie’s saving grace, so far as it has one. According to one version of the story, Darryl F. Zanuck saw an early cut of The I Don’t Care Girl, realized it was a dog, and ordered drastic surgery: he called in Jack Cole to punch up the musical numbers. And for the three numbers Cole staged — “Beale Street Blues”, “The Johnson Rag” and “I Don’t Care” (shown here) — the movie blazes fitfully to life. Of course, when Cole takes over, the vaudeville of 1910 flies out the window while 1950s theatrical jazz dance sashays in the door (other numbers staged by Seymour Felix are truer to the period, if less flamboyantly entertaining). Besides Cole’s work, The I Don’t Care Girl has little to recommend it, although the print shown at Cinevent beautifully conveyed the movie’s other main asset, the splendid Fox Technicolor.

Which brings us to the movie’s saving grace, so far as it has one. According to one version of the story, Darryl F. Zanuck saw an early cut of The I Don’t Care Girl, realized it was a dog, and ordered drastic surgery: he called in Jack Cole to punch up the musical numbers. And for the three numbers Cole staged — “Beale Street Blues”, “The Johnson Rag” and “I Don’t Care” (shown here) — the movie blazes fitfully to life. Of course, when Cole takes over, the vaudeville of 1910 flies out the window while 1950s theatrical jazz dance sashays in the door (other numbers staged by Seymour Felix are truer to the period, if less flamboyantly entertaining). Besides Cole’s work, The I Don’t Care Girl has little to recommend it, although the print shown at Cinevent beautifully conveyed the movie’s other main asset, the splendid Fox Technicolor. Much of the rest of the day, until the dinner break anyhow, was almost anticlimactic after the gaudy Technicolor splash of The I Don’t Care Girl.

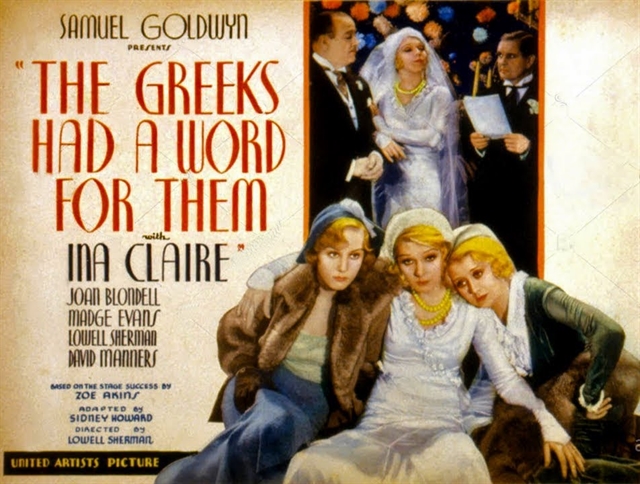

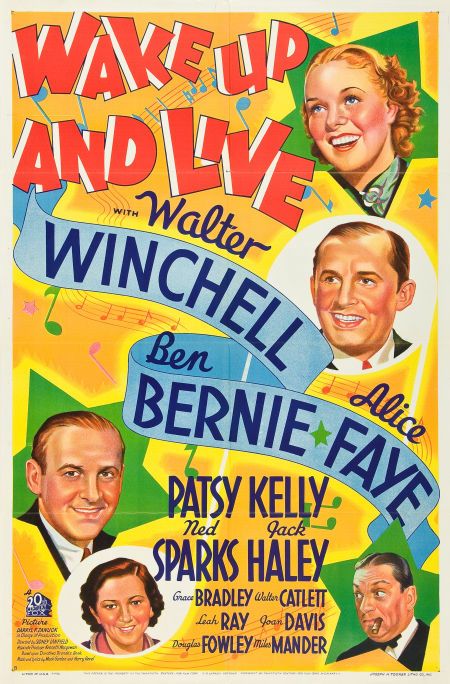

Much of the rest of the day, until the dinner break anyhow, was almost anticlimactic after the gaudy Technicolor splash of The I Don’t Care Girl.  Then, just like that, the anticlimactic part of the day was over and Richard Barrios was back to introduce

Then, just like that, the anticlimactic part of the day was over and Richard Barrios was back to introduce  After dinner we saw a real crowd-pleaser, and a highlight of the weekend:

After dinner we saw a real crowd-pleaser, and a highlight of the weekend:  The last movie of the day was one I’ve been curious about for some time:

The last movie of the day was one I’ve been curious about for some time: