Heading into the home stretch of this first Columbus Moving Picture Show, we saw…I believe the customary term is “the thrilling conclusion” with Chapters 9-12 of Adventures of Red Ryder. Justice triumphed, bad guys got what was coming to them (banker Drake met a particularly grisly end), and surviving good guys lived happily until the next adventure — which came in the funny papers, on radio, and in B-western features; there were to be no more serials.

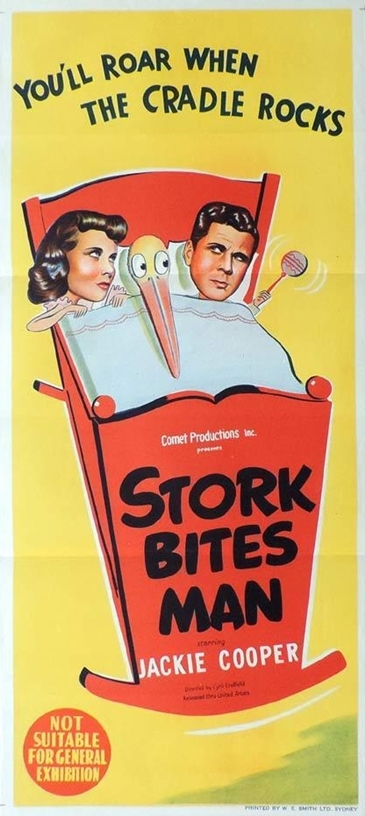

Then we saw former child star Jackie Cooper in the first of 73 adult roles in his 61-year career: Stork Bites Man (1947). This was the second picture for which I contributed notes to The Picture Show program, and here they are:

Then we saw former child star Jackie Cooper in the first of 73 adult roles in his 61-year career: Stork Bites Man (1947). This was the second picture for which I contributed notes to The Picture Show program, and here they are:

In 1945 Mary Pickford, still dabbling in movies from her boozy retirement at Pickfair, formed a production company, Comet Pictures, with husband Charles “Buddy” Rogers and Ralph Cohn. Cohn was the son of Jack and nephew of Harry, the battling brothers who were always at each other’s throats over the running of Columbia Pictures, where Ralph had been a B-picture producer, turning out installments in the Crime Doctor, Lone Wolf, Boston Blackie and Ellery Queen series, along with other low-budget efforts.

The model for Comet Pictures was Hal Roach’s “Streamliners”, mid-length pictures longer than short subjects but less than an hour long and aimed at the bottom slot on double features. Comet productions came in right around 65 minutes, as does our specimen, Stork Bites Man.

The germ of Stork Bites Man was a slim book by Louis Pollock, subtitled “What the Expectant Father May Expect”. Pollock’s comic treatise, dedicated to the proposition that no man is ever ready for fatherhood, never made the bestseller lists. But being published in 1945 during the waning months of World War II, it fortuitously caught the leading edge of the Baby Boom, when millions of returning servicemen were poised to go through what Pollock wrote about.

In adapting Stork Bites Man to the screen in 1947, there was a catch: Most of what Pollock wrote about was frowned upon by the Production Code, if not downright forbidden. This included such things as morning sickness, food cravings, mood swings, a high-strung wife losing (temporarily) her figure — even the words “pregnant” and “pregnancy” themselves. Writer/director Cyril (“Cy”) Endfield and adapter Fred Freiberger met the challenge by changing the story’s focus: Instead of Lou Pollock coping with his wife Cleta’s nine expectant months, their theme was America’s post-war housing shortage.

And so it was that Lou and Cleta Pollock were renamed Ernie Brown (Jackie Cooper) and his wife Peg (Gene Roberts, later to change her name to Meg Randall), resident managers of an apartment house. The landlord (Emory Parnell) doesn’t allow families with children, and housing being a seller’s market after American industry’s four years of single-minded focus on wartime production, he’s able to get away with it. The first half of the picture chronicles Ernie’s efforts to keep Peg’s condition secret from the boss. Inevitably, once the cat is out of the bag (if you’ll pardon the expression), Ernie is fired, he and Peg are evicted, and Ernie decides to organize a strike among workers and tenants to force a change of policy.

And so it was that Lou and Cleta Pollock were renamed Ernie Brown (Jackie Cooper) and his wife Peg (Gene Roberts, later to change her name to Meg Randall), resident managers of an apartment house. The landlord (Emory Parnell) doesn’t allow families with children, and housing being a seller’s market after American industry’s four years of single-minded focus on wartime production, he’s able to get away with it. The first half of the picture chronicles Ernie’s efforts to keep Peg’s condition secret from the boss. Inevitably, once the cat is out of the bag (if you’ll pardon the expression), Ernie is fired, he and Peg are evicted, and Ernie decides to organize a strike among workers and tenants to force a change of policy.

Variety found Stork Bites Man a “lightweight comedy that’ll serve for dualers,” reserving special praise for Jackie Cooper and co-star Gus Schilling as a baby-supplies salesman. Still, amusing as it was, its theme of the little guy organizing against the hard-hearted plutocracy was the kind of candy-coated leftism that would in time draw the baleful attention of the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Cy Endfield’s time came in 1951; blacklisted for his Young Communist League activism at Yale in the 1930s, he relocated to the U.K., where he worked for a while under various aliases, finally resuming his real name in 1957. Depending on your point of view, his directing career peaked either with the 1961 Jules Verne fantasy The Mysterious Island (with visual effects by the great Ray Harryhausen) or with 1964’s Zulu, about the battle of Rorke’s Drift during the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879 (starring Stanley Baker, Jack Hawkins, and the up-and-coming Michael Caine). Endfield lost interest in filmmaking in 1971, but he remained an author, inventor, and amateur magician for the rest of his life; he died in England in 1995, age 80.

Comet Pictures, alas, fizzled after only four releases; Stork Bites Man was probably its best, and certainly its last. Cy Endfield (as noted) moved to England. Ralph Cohn returned to Columbia to head Screen Gems, the studio’s TV distribution wing. Fred Freiberger went on to produce The Six Million Dollar Man, Space: 1999 and the original Star Trek, among other TV programs. Buddy Rogers and Mary Pickford, of course, retreated to Pickfair, where Buddy became Mary’s devoted caretaker for the rest of her long life, and custodian of her legend for the rest of his.

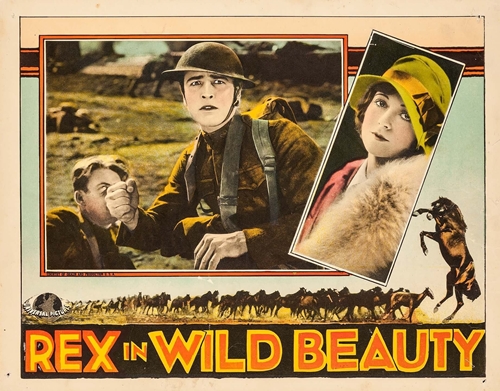

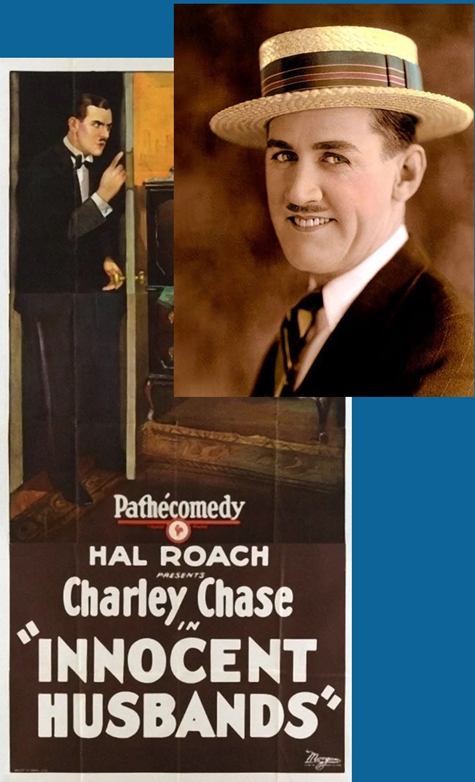

Wild Beauty (1927) was a vehicle for the equine star Rex, who was introduced to audiences in The King of the Wild Horses (1924, screened at Cinevent 50 in 2018). Rex was “discovered” by Hal Roach, who used Rex to get his feet wet in feature production. Rex has the distinction of being the only horse in history to become a genuine movie star without (literally) supporting some human cowboy star. With Rex it was the other way around: In his pictures, the humans (figuratively) supported him. In the course of his career, which lasted until 1938, he was variously billed as “Rex the Wonder Horse” or (echoing the title of his film debut) “King of the Wild Horses”. By the time of Wild Beauty, Hal Roach had decided to postpone his move into features a few years, so he sold Rex to Carl Laemmle over at Universal. The plot of this first Universal Rex picture had human hero Hugh Allen rescuing a mare he names “Valerie” from the battlefields of the Great War; he brings her home, where wild stallion Rex tries to lure her away from the ranch. Soon Rex is vying for Valerie’s attention with another stallion named Starbright. Meanwhile, there’s a parallel human romance between rancher Hugh Allen and June Marlowe — later, with blonde hair, to be beloved by generations of children as Miss Crabtree in the Our Gang shorts. But June Marlowe’s glory years were still in the future, and does anybody know or remember who Hugh Allen was? (Actually, his birth name was Allan Hughes; the spelling of his professional surname varied between “Allan” and “Allen”. He lived to be 93 but his film career ended at 27 without making the slightest impression.)

The humans hardly matter, though; Rex is pretty much the whole show. Now he makes an impression. Elinor Glyn, the British erotic novelist, famously tagged Clara Bow as having “It“, that elusive, hard-to-pinpoint magnetic power that attracts both sexes. According to Mme. Glyn, Rex had it too: “Rex has ‘it’ and if I could only find a leading man with the same look in his eye, my quest would be finished. He is not just a horse. He has personality and he exudes something beyond all this, and that is the spirit of romance.” I don’t know if Mme. Glyn’s words sounded as vaguely alarming in the 1920s as they do now, but there’s no denying that Rex had something, nor that the camera found it a joy to behold. And it wasn’t just the tricks he learned from a trainer. The buzz is that, like a number of human stars, Rex was notoriously difficult to work with — in Rex’s case, owing to some pretty brutal abuse in his early years. The difference, in Rex’s case, was that “difficult” could translate to “murderous” when you weigh approximately 1,400 pounds. Dangerous and unpredictable — maybe that’s what comes through on screen, and what gave Rex “It“.

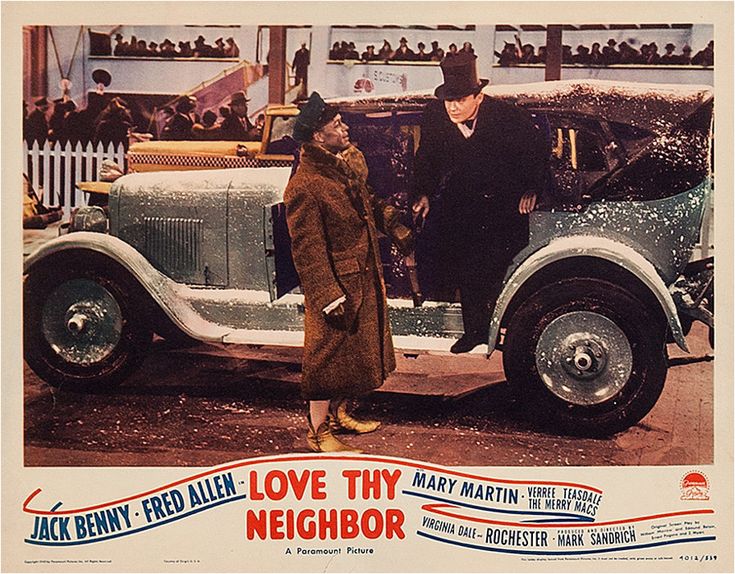

Love Thy Neighbor (1940) provided the final highlight of the weekend. Expertly directed by the nimble Mark Sandrich, it capitalized on the p.r. “feud” between radio comedians Jack Benny at NBC and Fred Allen over at CBS, much the way 1937’s Wake Up and Live (Cinevent 51, Day 2) exploited the equally spurious clash between Walter Winchell and Ben Bernie. Allen and Benny were both professional funny men, so it was generally understood that their feud was all in fun; no one ever seems to have taken it seriously, as some did Bernie and Winchell’s.

Love Thy Neighbor (1940) provided the final highlight of the weekend. Expertly directed by the nimble Mark Sandrich, it capitalized on the p.r. “feud” between radio comedians Jack Benny at NBC and Fred Allen over at CBS, much the way 1937’s Wake Up and Live (Cinevent 51, Day 2) exploited the equally spurious clash between Walter Winchell and Ben Bernie. Allen and Benny were both professional funny men, so it was generally understood that their feud was all in fun; no one ever seems to have taken it seriously, as some did Bernie and Winchell’s.

The plot of Love Thy Neighbor offered new-minted Broadway star Mary Martin as Fred Allen’s (fictitious) niece Mary Allen. Mary goes to Benny’s office in an effort to negotiate a truce between the two men, then in a case of mistaken identity, she auditions for and gets cast as the leading lady of Benny’s new stage show, under the name of Virginia Astor. In Miami for rehearsals and the out-of-town opening, Benny winds up in a hotel suite next to Allen, who is also in Miami under doctor’s orders to work off the stress of the feud. While they’re all in Miami, with Mary walking the tightrope between her uncle and her boss, the real Virginia Astor (Virginia Dale) shows up, and…well, imagine the possibilities.

Love Thy Neighbor came midway in the three or four years during which Mary Martin tried and failed to transfer her stage stardom to the screen. Like her great rival Ethel Merman, there was something in her star persona that simply didn’t photograph well. In Merman’s case, she tended to come off as too big and brassy for the screen, even in the early years when she was still rather petite (and even a bit of a “dish”). With Martin, it wasn’t “too big”, but “too chilly”; somehow the camera didn’t warm to her, and neither did audiences. (Not until the 1950s, with TV productions of Peter Pan and Annie Get Your Gun did Martin approach her Broadway success, and those performances — preserved, thank God — remain the best record we have of her.) Martin isn’t quite able to provide the musical spice to Love Thy Neighbor that Alice Faye did to Wake Up and Live, but she at least is allowed to perform her first signature song, Cole Porter’s “My Heart Belongs to Daddy”, slightly bowdlerized but within two years of introducing it.

What musical spice Love Thy Neighbor contains is rather fleeting, and from a surprising source. This is a nifty blend of Shakespeare and jitterbug entitled “Dearest, Darest I” by Johnny Burke and Jimmy Van Heusen, performed by Eddie Anderson as Benny’s valet Rochester and Theresa Harris as his girlfriend Josephine. Anderson was so famous for his role that he was often billed with “Rochester” as his middle name, and sometimes by that name alone. His gravelly voice (the result of ruptured vocal cords as a newsboy in his youth) meant that Dick Powell and Nelson Eddy’s jobs were safe, but Anderson could put a song over with personality, and that voice (plus the generosity of Jack Benny, who saw to it that he always got all the best lines) made him a star.

What musical spice Love Thy Neighbor contains is rather fleeting, and from a surprising source. This is a nifty blend of Shakespeare and jitterbug entitled “Dearest, Darest I” by Johnny Burke and Jimmy Van Heusen, performed by Eddie Anderson as Benny’s valet Rochester and Theresa Harris as his girlfriend Josephine. Anderson was so famous for his role that he was often billed with “Rochester” as his middle name, and sometimes by that name alone. His gravelly voice (the result of ruptured vocal cords as a newsboy in his youth) meant that Dick Powell and Nelson Eddy’s jobs were safe, but Anderson could put a song over with personality, and that voice (plus the generosity of Jack Benny, who saw to it that he always got all the best lines) made him a star.

Now a few words about Theresa Harris (1906-85). This woman is long overdue for some kind of recognition. Hollywood blogger Steve Cubine, in a 2019 post about Harris, said, “Hollywood just didn’t know what to do with the talented Miss Harris,” but that’s a crock. Hollywood knew damn well what to do with Theresa Harris, they just wouldn’t let her do it. She was beautiful, intelligent and sexy; she could act, she could sing, she could dance. And oh yes, she was African-American. So naturally, she played maids. In a little over 100 films in a little under 30 years, you could find her picking up after, dressing the hair of, or laying out clothes for more than half the leading ladies in Hollywood —  Lilyan Tashman, Thelma Todd, Lupe Velez, Ginger Rogers (twice), Margaret Lindsay, Barbara Stanwyck (twice), Mae Clarke, Constance Cummings, Billie Burke, Helen Morgan, Gloria Stuart, Claire Trevor, Bette Davis, Olivia de Havilland, Marlene Dietrich, Frances Dee, Betty Grable, Lillian Gish, June Haver, Maureen O’Hara, Gloria Grahame, Maureen O’Sullivan, Jane Greer, Audrey Totter, Kathryn Grayson, Ann Miller, Arlene Dahl, Jane Russell — you name her, chances are at some time or other you’ll see Theresa Harris standing behind her in a black dress and white lace cap, hands demurely folded in front of her. If she seldom got to show what she could really do, at least she was never used for coarse comic relief, and so could invest her roles with a dignity that plays well today — see her especially as Chico to Stanwyck’s Lily in Baby Face (1933) and as the wise house servant Alma in I Walked with a Zombie (’43). She was released from domestic service at least twice: Here in Love Thy Neighbor and in a previous turn as Rochester’s Josephine in another Jack Benny vehicle, Buck Benny Rides Again earlier in 1940. In that outing she and Anderson got to sing and dance “My My” by Frank Loesser and Jimmy McHugh. (It’s probably not a coincidence that Buck Benny was also directed by Mark Sandrich. Good for him.) There’s plenty of good work from Theresa Harris if you know where to look, but in those days of artistic apartheid, she is yet another example of a Great Star Who Never Was.

Lilyan Tashman, Thelma Todd, Lupe Velez, Ginger Rogers (twice), Margaret Lindsay, Barbara Stanwyck (twice), Mae Clarke, Constance Cummings, Billie Burke, Helen Morgan, Gloria Stuart, Claire Trevor, Bette Davis, Olivia de Havilland, Marlene Dietrich, Frances Dee, Betty Grable, Lillian Gish, June Haver, Maureen O’Hara, Gloria Grahame, Maureen O’Sullivan, Jane Greer, Audrey Totter, Kathryn Grayson, Ann Miller, Arlene Dahl, Jane Russell — you name her, chances are at some time or other you’ll see Theresa Harris standing behind her in a black dress and white lace cap, hands demurely folded in front of her. If she seldom got to show what she could really do, at least she was never used for coarse comic relief, and so could invest her roles with a dignity that plays well today — see her especially as Chico to Stanwyck’s Lily in Baby Face (1933) and as the wise house servant Alma in I Walked with a Zombie (’43). She was released from domestic service at least twice: Here in Love Thy Neighbor and in a previous turn as Rochester’s Josephine in another Jack Benny vehicle, Buck Benny Rides Again earlier in 1940. In that outing she and Anderson got to sing and dance “My My” by Frank Loesser and Jimmy McHugh. (It’s probably not a coincidence that Buck Benny was also directed by Mark Sandrich. Good for him.) There’s plenty of good work from Theresa Harris if you know where to look, but in those days of artistic apartheid, she is yet another example of a Great Star Who Never Was.

I was much looking forward to seeing The Student of Prague in Columbus this year, but I was laboring under a misunderstanding: I thought we were getting the 1926 silent with Conrad Veidt and Werner Krauss. Instead, it was The Student of Prague (1913), the earlier version. And considering how much cinema all over the world evolved between 1913 and 1926, it must be said that what we saw was a much earlier version. The picture tells the story of Balduin (Paul Wegener), a college student less interested in academics than in drinking, gambling, dueling, and — it is discreetly hinted — whoring (“The more things change…”). As Balduin fritters away his limited funds, he is approached by a whimsical old man named Scapinelli (John Gottowt). He offers Balduin a vast fortune (“100,000 pieces of gold”, “600,000 florins”, or other amounts, depending on which translation you watch) in exchange for any single item the old boy is able to find in Balduin’s lodging. Knowing he owns practically nothing, Balduin readily signs Scapinelli’s contract, and forthwith he is showered with a mountain of coins. He leads Scapinelli to his barely-furnished room, where the old man claims an item Balduin wouldn’t have thought was part of the deal: His reflection in the mirror.

Only momentarily dismayed at his failure to cast a reflection, Balduin sallies forth with his newfound funds, becoming the life of every party. But his reflection dogs his every move, becoming in effect his evil twin, and working mischief in the lives of Balduin and everyone around him — the barmaid who loves him (Lyda Salmonova, Wegener’s wife at the time), the countess whom he loves (Grete Berger), the countess’s fiancé (Fritz Weidemann). Things do not end well for anyone but Scapinelli.

The Student of Prague is widely regarded as “the first German art film”. But it’s an art film in comparison to what came before it, not to what came after. It wouldn’t be till after the Great War — to be precise, with The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) — that Germany vaulted to the front rank of world film. But Student has its points. The locations (it was actually shot in and around Prague) are attractive, the special effects surprisingly sophisticated — and most of all, there’s Paul Wegener. Wegener had a spectacular screen presence — in The Golem (1920) he gives one of the great performances of the silent era — and it comes through even in the blurriest versions of Student to be found on YouTube. Just take a gander at the lobby card above; notice how even with Lyda Salmonova flaunting her bare legs, your eye is drawn irresistibly to Wegener.

There are several copies of The Student of Prague available on YouTube. The best one I could find is this one — but some of the intertitles come and go quickly, so be prepared to pause as needed. The best reason to see it remains Paul Wegener. The 1926 remake is there too, with an excellent image but, alas, no translations for the German titles. If you read German, here it is, with Conrad Veidt as Balduin and Werner Krauss (the original Dr. Caligari) as Scapinelli. The remake is still on my bucket list, but Conrad Veidt has some mighty big shoes to fill.

Cigarette Girl (1947) brought The Picture Show to a close, not with a bang — but to be fair, not really with a whimper either. For the benefit of Cinedrome readers who are not of a Certain Age, a cigarette girl was an employee of a restaurant or night club who, like a cocktail waitress, roamed among the customers’ tables with a tray slung around her neck (as in this poster) offering tobacco products for sale: “Cigars…cigarettes…pipe tobacco…” This was a viable line of work in the days when (1) indoor smoking was not only legal, but everyone without exception smoked, and (2) a cigar or a pack of cigarettes could be had for small change — say, ten cents for a pack of Luckies or Camels, or a White Owl or Dutch Masters cigar. The girl usually had to buy her own stock, but she could get it wholesale, and the tips could be pretty good: If a guy wanted to impress a date, or to hit on the cigarette girl herself, he might slip her a buck for a dime pack of cigarettes and tell her to keep the change. At that rate, with luck, she could earn her month’s rent of, say, $45.00 in a couple or three nights.

Cigarette Girl (1947) brought The Picture Show to a close, not with a bang — but to be fair, not really with a whimper either. For the benefit of Cinedrome readers who are not of a Certain Age, a cigarette girl was an employee of a restaurant or night club who, like a cocktail waitress, roamed among the customers’ tables with a tray slung around her neck (as in this poster) offering tobacco products for sale: “Cigars…cigarettes…pipe tobacco…” This was a viable line of work in the days when (1) indoor smoking was not only legal, but everyone without exception smoked, and (2) a cigar or a pack of cigarettes could be had for small change — say, ten cents for a pack of Luckies or Camels, or a White Owl or Dutch Masters cigar. The girl usually had to buy her own stock, but she could get it wholesale, and the tips could be pretty good: If a guy wanted to impress a date, or to hit on the cigarette girl herself, he might slip her a buck for a dime pack of cigarettes and tell her to keep the change. At that rate, with luck, she could earn her month’s rent of, say, $45.00 in a couple or three nights.

End of history lesson. The cigarette girl of the title was played by Columbia contract player Leslie Brooks, the sort who played supports and bits in A-pictures and leads in B’s like this. Likewise leading man Jimmy Lloyd, and as a romantic team the two of them were blandly personable. They meet on neutral ground and launch a courtship under harmlessly false pretenses: She’s a “lowly” cigarette girl, but tells him she’s a popular night club singer; meanwhile he tells her he’s an oil company president (if memory serves, he’s really a gas station attendant). But lo and behold, their Little White Lies come true — by the final fadeout he’s a tycoon, she’s a Broadway star, and all’s right with the world. Russ Morgan and his Orchestra performed class arrangements to the songs by Doris Fisher and Allan Roberts — I sat there tapping my toes as the movie unspooled, though I couldn’t have hummed a single tune ten minutes after the lights came up. All in all, a pleasant palate-cleanser to close out the day, and the weekend.

Thus did The Columbus Moving Picture Show take up the Cinevent torch, banner, baton — fill in the metaphor of your choice — for 2022. Memorial Day 2023 will be here before any of us know it, so take my advice and make your plans now; start by getting on their mailing list and Liking them on Facebook. I hope to see you in Columbus next year. Don’t forget to say hi.

Then it was the welcome return of another longstanding Cinevent tradition: the

Then it was the welcome return of another longstanding Cinevent tradition: the  The cartoons were followed by

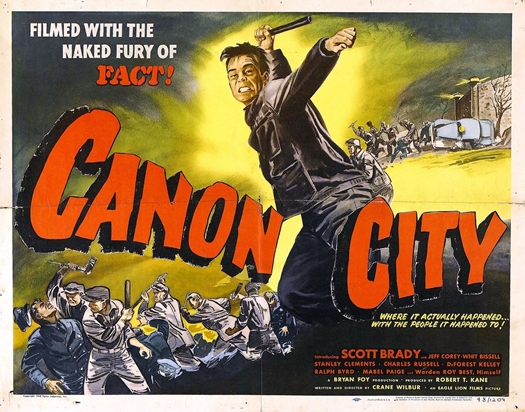

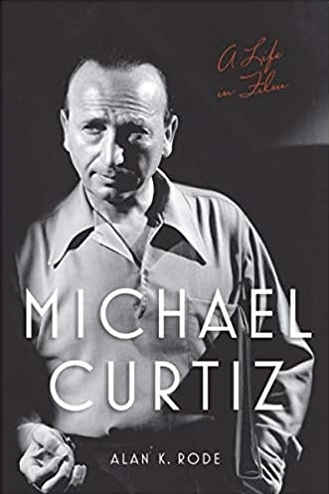

The cartoons were followed by  Okay, back to Columbus. Alan K. Rode, author of biographies of

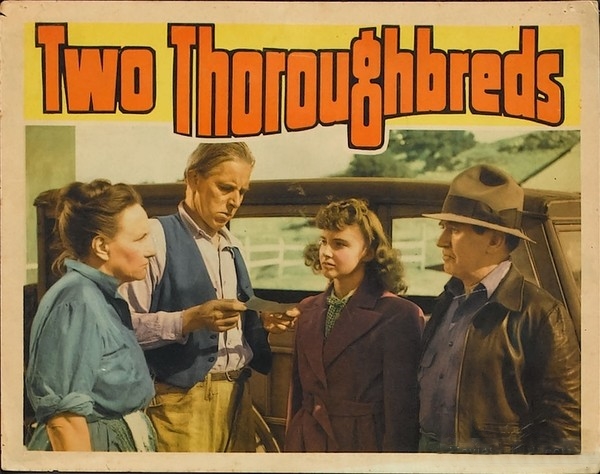

Okay, back to Columbus. Alan K. Rode, author of biographies of  From hard-boiled prison drama to wholesome family fare, next came

From hard-boiled prison drama to wholesome family fare, next came

The second and final Laurel and Hardy short of the weekend was

The second and final Laurel and Hardy short of the weekend was  Day 3 wrapped up with

Day 3 wrapped up with

The day’s first feature was

The day’s first feature was  If you think I’m building up to telling you that Valiant Is the Word for Carrie was screened at this year’s Picture Show, I’m not. I’m setting up one of the most exquisitely hilarious jokes in movie history, one that everyone understood at the time, but which nobody gets anymore. It so happens that the following year, the Three Stooges came out with one of their best-remembered shorts. It’s still very popular, but its most brilliant joke, which goes over the head of every Stooges fan today, is its title:

If you think I’m building up to telling you that Valiant Is the Word for Carrie was screened at this year’s Picture Show, I’m not. I’m setting up one of the most exquisitely hilarious jokes in movie history, one that everyone understood at the time, but which nobody gets anymore. It so happens that the following year, the Three Stooges came out with one of their best-remembered shorts. It’s still very popular, but its most brilliant joke, which goes over the head of every Stooges fan today, is its title:  The title of

The title of  The last feature before dinner was the earliest of the whole weekend:

The last feature before dinner was the earliest of the whole weekend:  After the dinner break we leapt forward 98 years, from the earliest movie at The Picture Show to the most recent. This was

After the dinner break we leapt forward 98 years, from the earliest movie at The Picture Show to the most recent. This was  Bride of Finklestein also served as a kind of lead-in to the next feature, which was introduced by Nick (“Benny Biffle”) Santa Maria. This was

Bride of Finklestein also served as a kind of lead-in to the next feature, which was introduced by Nick (“Benny Biffle”) Santa Maria. This was  Day 2 wrapped up with

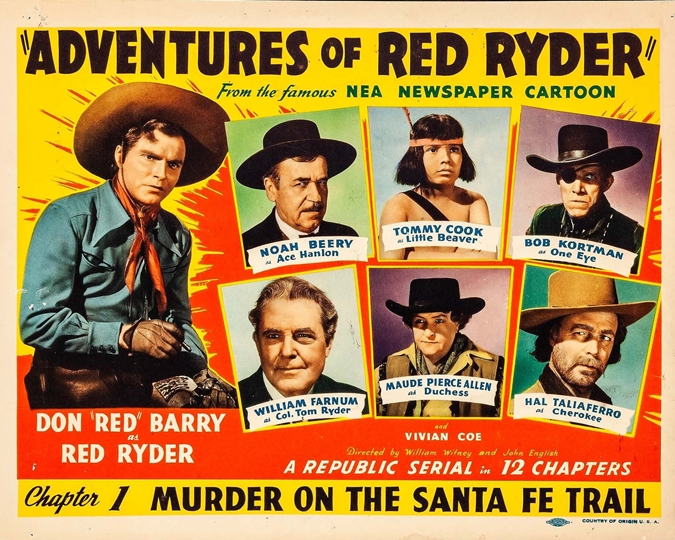

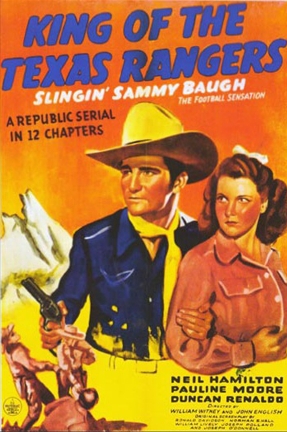

Day 2 wrapped up with  A feature of the last few Cinevents that The Picture Show wisely chose to continue this year is the 12-chapter serial, screening three chapters at the beginning of each of the convention’s four days. As in prior years, this year’s serial was from Republic — naturally enough, since Republic was, well, if not the Tiffany’s, at least the Zale’s of chapter-play production. And after the relatively exotic serials of the last few years — with heroes taking on a Japanese spy ring during World War II (The Masked Marvel, Cinevent 50), lost-world savages on a volcanic island above the Arctic Circle (Hawk of the Wilderness, C-51), and Teutonic saboteurs before America’s entry into the war (King of the Texas Rangers, C-52) — this one, for a refreshing change of pace, was a standard, good old-fashioned cowboy shoot-’em-up,

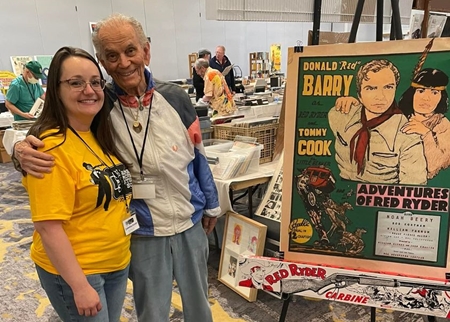

A feature of the last few Cinevents that The Picture Show wisely chose to continue this year is the 12-chapter serial, screening three chapters at the beginning of each of the convention’s four days. As in prior years, this year’s serial was from Republic — naturally enough, since Republic was, well, if not the Tiffany’s, at least the Zale’s of chapter-play production. And after the relatively exotic serials of the last few years — with heroes taking on a Japanese spy ring during World War II (The Masked Marvel, Cinevent 50), lost-world savages on a volcanic island above the Arctic Circle (Hawk of the Wilderness, C-51), and Teutonic saboteurs before America’s entry into the war (King of the Texas Rangers, C-52) — this one, for a refreshing change of pace, was a standard, good old-fashioned cowboy shoot-’em-up,  Little Beaver was played by nine-year-old Tommy Cook, who is not only still with us at 91 (the last survivor of this or any other Republic serial), but was an honored guest in Columbus; here he is shown with Picture Show Chair Samantha Glasser in the Dealers Room. (And by the way, do you see what’s hanging on the easel under the poster for the serial? Yep, it’s a Daisy Red Ryder BB gun. They raffled one off during the weekend — albeit with no compass or sundial in the stock — and I admit I was tempted for a second or two. But [1] I’d never have gotten it on the plane; and [2] even if I had it shipped to my home, what could I do with it then? I’d probably just shoot my eye out.)

Little Beaver was played by nine-year-old Tommy Cook, who is not only still with us at 91 (the last survivor of this or any other Republic serial), but was an honored guest in Columbus; here he is shown with Picture Show Chair Samantha Glasser in the Dealers Room. (And by the way, do you see what’s hanging on the easel under the poster for the serial? Yep, it’s a Daisy Red Ryder BB gun. They raffled one off during the weekend — albeit with no compass or sundial in the stock — and I admit I was tempted for a second or two. But [1] I’d never have gotten it on the plane; and [2] even if I had it shipped to my home, what could I do with it then? I’d probably just shoot my eye out.) The first feature of the weekend,

The first feature of the weekend,  Behind the News was also the swan song of Doris Davenport after six years and nine pictures, four of them with no screen credit. At the beginning and end of those six years she did seem to be going places. Her first picture was in 1934, playing Eddie Cantor’s girlfriend in Kid Millions. Other bits followed, interspersed with fashion modeling to make ends meet. In 1938, under the name Doris Jordan, she tested for Scarlett O’Hara in Gone With the Wind and, according to Dave Domagala’s program notes, “was actually one of the finalists.” (Well, actually, “one of the semi-finalists” is more like it. On November 18, 1938, David Selznick listed his Scarlett front-runners as Paulette Goddard, Doris Jordan, Jean Arthur, Katharine Hepburn, and Loretta Young, adding that “Jordan is a complete amateur”. By December 12, Selznick was writing, “it’s narrowed down to Paulette, Jean Arthur, Joan Bennett, and Vivien Leigh” — with Leigh having the inside track.) Doris Jordan/Davenport’s test for Scarlett impressed producer Samuel Goldwyn enough to get her cast in The Westerner (1940) opposite Gary Cooper for director William Wyler. Wyler wasn’t impressed (he wanted her part for his wife, Margaret Tallichet), but Goldwyn thought she had real star potential. After that came Behind the News — then nothing. Some sources say she simply got no further offers, though it seems likely that if nothing else, Republic at least could have found something for her to do. One dramatic story, attributed to David Ragan’s Who’s Who in Hollywood but unconfirmed anywhere else, claims that an auto accident after shooting The Westerner crushed her legs and forced her to use a cane for the rest of her days. Grain of salt on that one, I think; if that’s true, then how did she make Beyond the News? Whatever the reason, Doris Davenport lived on until 1980 but never made another picture.

Behind the News was also the swan song of Doris Davenport after six years and nine pictures, four of them with no screen credit. At the beginning and end of those six years she did seem to be going places. Her first picture was in 1934, playing Eddie Cantor’s girlfriend in Kid Millions. Other bits followed, interspersed with fashion modeling to make ends meet. In 1938, under the name Doris Jordan, she tested for Scarlett O’Hara in Gone With the Wind and, according to Dave Domagala’s program notes, “was actually one of the finalists.” (Well, actually, “one of the semi-finalists” is more like it. On November 18, 1938, David Selznick listed his Scarlett front-runners as Paulette Goddard, Doris Jordan, Jean Arthur, Katharine Hepburn, and Loretta Young, adding that “Jordan is a complete amateur”. By December 12, Selznick was writing, “it’s narrowed down to Paulette, Jean Arthur, Joan Bennett, and Vivien Leigh” — with Leigh having the inside track.) Doris Jordan/Davenport’s test for Scarlett impressed producer Samuel Goldwyn enough to get her cast in The Westerner (1940) opposite Gary Cooper for director William Wyler. Wyler wasn’t impressed (he wanted her part for his wife, Margaret Tallichet), but Goldwyn thought she had real star potential. After that came Behind the News — then nothing. Some sources say she simply got no further offers, though it seems likely that if nothing else, Republic at least could have found something for her to do. One dramatic story, attributed to David Ragan’s Who’s Who in Hollywood but unconfirmed anywhere else, claims that an auto accident after shooting The Westerner crushed her legs and forced her to use a cane for the rest of her days. Grain of salt on that one, I think; if that’s true, then how did she make Beyond the News? Whatever the reason, Doris Davenport lived on until 1980 but never made another picture.

Still, Love Among the Millionaires was a hit — the true measure of Clara’s stardom, as with all stars past, present and future, was that she was expected and able to carry material like this. To be fair, she didn’t bear the burden alone. She got good support from 9-year-old Mitzi Green (shown here) as her brassy sister, Charles Sellon as their father, and Stanley Smith as Clara’s boyish sweetheart. Comic relief was provided by Stuart Erwin and Skeets Gallagher as two would-be suitors for Clara’s hand — although frankly, they come off more as a bickering couple than as romantic rivals.

Still, Love Among the Millionaires was a hit — the true measure of Clara’s stardom, as with all stars past, present and future, was that she was expected and able to carry material like this. To be fair, she didn’t bear the burden alone. She got good support from 9-year-old Mitzi Green (shown here) as her brassy sister, Charles Sellon as their father, and Stanley Smith as Clara’s boyish sweetheart. Comic relief was provided by Stuart Erwin and Skeets Gallagher as two would-be suitors for Clara’s hand — although frankly, they come off more as a bickering couple than as romantic rivals.

Marry Me Again

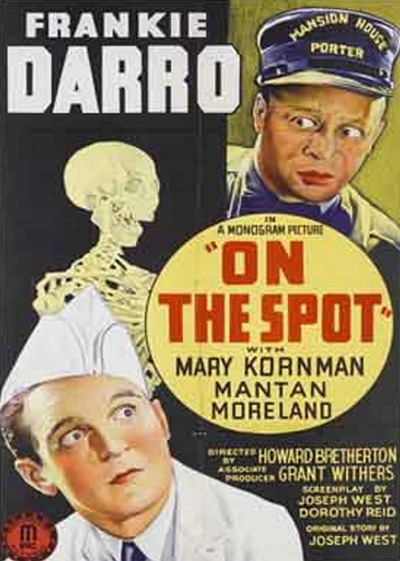

Marry Me Again The first day wrapped up with a diverting low-camp thriller from Monogram,

The first day wrapped up with a diverting low-camp thriller from Monogram,  I’m back from Columbus, where Memorial Day Weekend was always Cinevent Weekend until 2019, when Cinevent Chair Michael Haynes announced that Cinevent 52 in 2020 would be the last — but that the tradition of a Memorial Day classic movie convention in Ohio’s capital would continue under a new name (to be determined) and new management (albeit with many familiar faces performing the same volunteer services as before).

I’m back from Columbus, where Memorial Day Weekend was always Cinevent Weekend until 2019, when Cinevent Chair Michael Haynes announced that Cinevent 52 in 2020 would be the last — but that the tradition of a Memorial Day classic movie convention in Ohio’s capital would continue under a new name (to be determined) and new management (albeit with many familiar faces performing the same volunteer services as before). Last October brought the final installment of Cinevent, presented in conjunction with the fledgling Columbus Moving Picture Show. Cinevent’s Michael Haynes passed the torch to Samantha Glasser (right), who stepped up from Dealers Coordinator to Chair, overseeing the activities of a cadre of dedicated Cinevent volunteers, who elected (unanimously, as far as I could tell) to continue under the new banner.

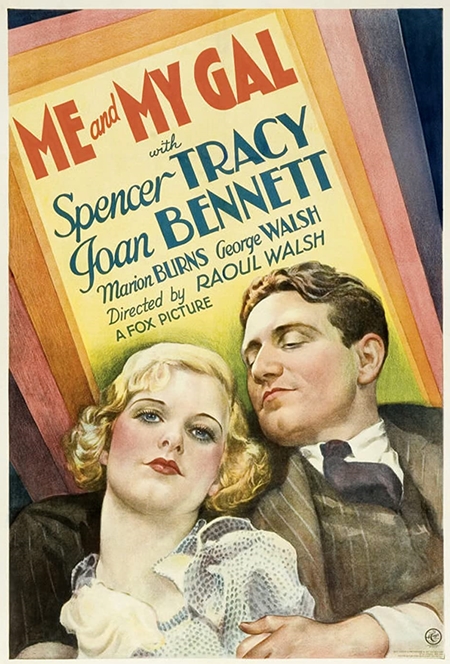

Last October brought the final installment of Cinevent, presented in conjunction with the fledgling Columbus Moving Picture Show. Cinevent’s Michael Haynes passed the torch to Samantha Glasser (right), who stepped up from Dealers Coordinator to Chair, overseeing the activities of a cadre of dedicated Cinevent volunteers, who elected (unanimously, as far as I could tell) to continue under the new banner. Well, whether the Wexner Center admitted it or not, Pre-Code at Fox is what we got, starting with Me and My Gal (1932, not to be confused with For Me and My Gal, the Judy Garland/Gene Kelly MGM musical of ten years later). This one was an urban melo-dramedy directed by Raoul Walsh and starring Spencer Tracy and Joan Bennett. The story wasn’t much. Tracy played Danny Dolan, a happy-go-lucky waterfront cop who takes a shine to Helen (Bennett), a waitress in a greasy spoon on his beat. Meanwhile, her sister Kate (Marion Burns), though married to an adoring nice-guy dork, can’t resist her gangster ex-boyfriend Duke (George Walsh), who has her wrapped around (phallic symbol alert!) his little finger. While hubby is away in the merchant marine, Duke breaks out of prison and Kate hides him in the attic of the apartment she shares with her father-in-law, who is mute and wheelchair-bound from a stroke.

Well, whether the Wexner Center admitted it or not, Pre-Code at Fox is what we got, starting with Me and My Gal (1932, not to be confused with For Me and My Gal, the Judy Garland/Gene Kelly MGM musical of ten years later). This one was an urban melo-dramedy directed by Raoul Walsh and starring Spencer Tracy and Joan Bennett. The story wasn’t much. Tracy played Danny Dolan, a happy-go-lucky waterfront cop who takes a shine to Helen (Bennett), a waitress in a greasy spoon on his beat. Meanwhile, her sister Kate (Marion Burns), though married to an adoring nice-guy dork, can’t resist her gangster ex-boyfriend Duke (George Walsh), who has her wrapped around (phallic symbol alert!) his little finger. While hubby is away in the merchant marine, Duke breaks out of prison and Kate hides him in the attic of the apartment she shares with her father-in-law, who is mute and wheelchair-bound from a stroke. That’s just a sample of the banter. The picture has other things going for it besides two stars in the peppery bloom of youth: reliable old J. Farrell MacDonald as Helen and Kate’s father; Henry B. Walthall, D.W. Griffith’s first leading man, as Kate’s disabled father-in-law, still conveying profound emotion without uttering a sound; Raoul Walsh’s feel for the unpretentiousness of working-class life. (On the other hand, there’s Bert Hanlon as a drunken fisherman hanging out in Helen’s diner, quickly wearing out his welcome with her — and even more quickly with us.)

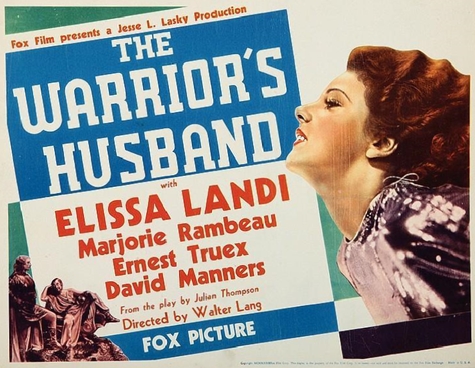

That’s just a sample of the banter. The picture has other things going for it besides two stars in the peppery bloom of youth: reliable old J. Farrell MacDonald as Helen and Kate’s father; Henry B. Walthall, D.W. Griffith’s first leading man, as Kate’s disabled father-in-law, still conveying profound emotion without uttering a sound; Raoul Walsh’s feel for the unpretentiousness of working-class life. (On the other hand, there’s Bert Hanlon as a drunken fisherman hanging out in Helen’s diner, quickly wearing out his welcome with her — and even more quickly with us.) The evening’s other feature, alas, isn’t so readily available. This was The Warrior’s Husband (1933), a title that sounded more of an oxymoron at the time than it does now. It’s too bad it’s not easy to get to see, because it is hands-down one of the great what-the-hell-is-this??? movies of the 1930s. The Wexner Center presented it in a sparkling brand-new 4K digital transfer, so there may be hope for a DVD or streaming option sometime in the future. If it does happen, you really want to take a gander at this thing.

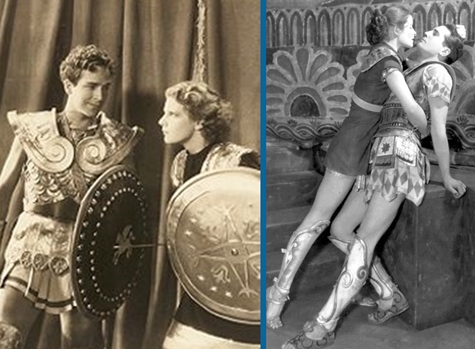

The evening’s other feature, alas, isn’t so readily available. This was The Warrior’s Husband (1933), a title that sounded more of an oxymoron at the time than it does now. It’s too bad it’s not easy to get to see, because it is hands-down one of the great what-the-hell-is-this??? movies of the 1930s. The Wexner Center presented it in a sparkling brand-new 4K digital transfer, so there may be hope for a DVD or streaming option sometime in the future. If it does happen, you really want to take a gander at this thing. Later that year, when Fox purchased the movie rights to the play, Hepburn was otherwise engaged, so her role went to Fox’s new contract discovery Elissa Landi. And no kidding, in the finished film Landi looks like nothing so much as — wait for it — Katharine Hepburn. This was understandable, since Hepburn was the current Big Thing, and Fox had plans to make Landi the next Big Thing. She had already made an impression on loan to Paramount and Cecil B. DeMille for The Sign of the Cross. Her timorous Christian damsel in that Roman spectacle pales beside her swaggering pagan Antiope; if The Warrior’s Husband were as widely available as The Sign of the Cross, this might be the picture she’s best remembered for today. Here are dueling Antiopes, Landi’s from the movie beside Hepburn’s from the stage; it’s not easy to tell them apart.

Later that year, when Fox purchased the movie rights to the play, Hepburn was otherwise engaged, so her role went to Fox’s new contract discovery Elissa Landi. And no kidding, in the finished film Landi looks like nothing so much as — wait for it — Katharine Hepburn. This was understandable, since Hepburn was the current Big Thing, and Fox had plans to make Landi the next Big Thing. She had already made an impression on loan to Paramount and Cecil B. DeMille for The Sign of the Cross. Her timorous Christian damsel in that Roman spectacle pales beside her swaggering pagan Antiope; if The Warrior’s Husband were as widely available as The Sign of the Cross, this might be the picture she’s best remembered for today. Here are dueling Antiopes, Landi’s from the movie beside Hepburn’s from the stage; it’s not easy to tell them apart. It also gives Hippolyta’s spouse Sapiens (Ernest Truex) ideas above his station. Sapiens (or “Sap”) shares with Theseus the “warrior’s husband” designation of the title, and his newfound assertiveness makes him an ancient advocate of men’s liberation (I guess you’d call him an early “masculist”).

It also gives Hippolyta’s spouse Sapiens (Ernest Truex) ideas above his station. Sapiens (or “Sap”) shares with Theseus the “warrior’s husband” designation of the title, and his newfound assertiveness makes him an ancient advocate of men’s liberation (I guess you’d call him an early “masculist”).

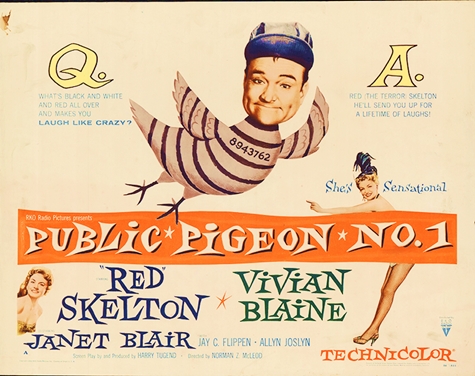

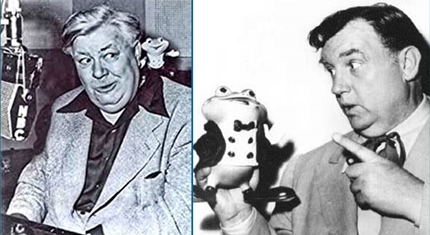

Day 4 of Cinevent 52 landed on October 31, Halloween itself. In keeping with the spirit of the day, the weekend’s Halloween theme made one final appearance in the form of a kinescope (film transcription of a live TV broadcast) excerpt from The Red Skelton Show of June 17, 1954. The 20-minute sketch — titled “Dial ‘B’ for Brush”, a reference to Hitchcock’s Dial “M” for Murder, then in release — offered Red’s dimwit character Clem Kadiddlehopper as a door-to-door brush salesman with just the kind of empty brain the local mad scientist is looking for to complete his latest sinister experiment. Guests on the episode, shown here with Red/Clem, were (left to right) TV horror-movie host and “glamour ghoul” Vampira (née Maila Elizabeth Niemi), Lon Chaney Jr., and the one and only Bela Lugosi. It was primitive fun; as would often be the case with Skelton’s long-running program, the flubs, mishaps, accidents and ad-libs were funnier than the script.

Day 4 of Cinevent 52 landed on October 31, Halloween itself. In keeping with the spirit of the day, the weekend’s Halloween theme made one final appearance in the form of a kinescope (film transcription of a live TV broadcast) excerpt from The Red Skelton Show of June 17, 1954. The 20-minute sketch — titled “Dial ‘B’ for Brush”, a reference to Hitchcock’s Dial “M” for Murder, then in release — offered Red’s dimwit character Clem Kadiddlehopper as a door-to-door brush salesman with just the kind of empty brain the local mad scientist is looking for to complete his latest sinister experiment. Guests on the episode, shown here with Red/Clem, were (left to right) TV horror-movie host and “glamour ghoul” Vampira (née Maila Elizabeth Niemi), Lon Chaney Jr., and the one and only Bela Lugosi. It was primitive fun; as would often be the case with Skelton’s long-running program, the flubs, mishaps, accidents and ad-libs were funnier than the script.

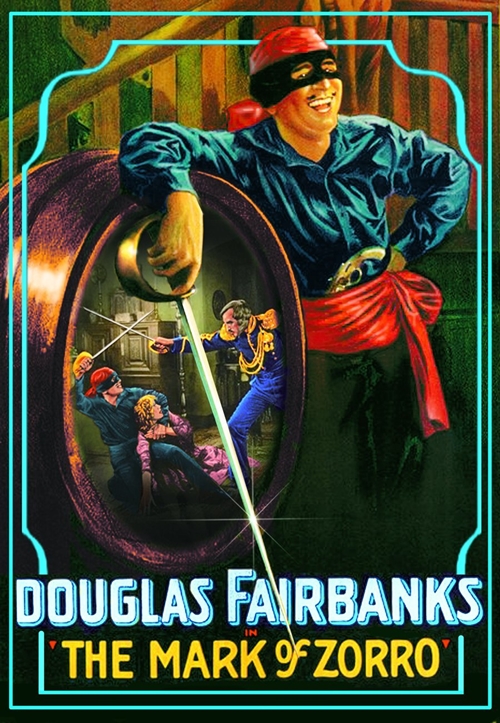

The Mark of Zorro (1920)

The Mark of Zorro (1920) The last movie of the day — of the whole weekend, and of Cinevent’s 52-year history — was

The last movie of the day — of the whole weekend, and of Cinevent’s 52-year history — was  One of my favorites this year was the first one,

One of my favorites this year was the first one,  After the animation program, the Saturday kiddie matinee vibe continued, as it has most years — this time with a trio of silent Our Gang shorts from Hal Roach:

After the animation program, the Saturday kiddie matinee vibe continued, as it has most years — this time with a trio of silent Our Gang shorts from Hal Roach:  Back from lunch break, we saw

Back from lunch break, we saw  After Scott and Alan’s colloquy (moderated by Caroline Breder-Watts) Alan introduced another Michael Curtiz Pre-Code,

After Scott and Alan’s colloquy (moderated by Caroline Breder-Watts) Alan introduced another Michael Curtiz Pre-Code,  Then came

Then came  The day finished up with…oh jeez, how shall I put this?…one of the most indelible screenings of the whole weekend. This was

The day finished up with…oh jeez, how shall I put this?…one of the most indelible screenings of the whole weekend. This was  Just as Sabaka was going into release in 1954 — and in a possibly unrelated development — Smilin’ Ed McConnell dropped dead unexpectedly of a heart attack at 62. He was replaced by Andy Devine, and the show became Andy’s Gang until it finally ran its course at the end of 1960. Baby Boomers of a Slightly Younger Age may remember that incarnation of Froggy, Midnight, Gunga Ram and the rest of the gang.

Just as Sabaka was going into release in 1954 — and in a possibly unrelated development — Smilin’ Ed McConnell dropped dead unexpectedly of a heart attack at 62. He was replaced by Andy Devine, and the show became Andy’s Gang until it finally ran its course at the end of 1960. Baby Boomers of a Slightly Younger Age may remember that incarnation of Froggy, Midnight, Gunga Ram and the rest of the gang. The first feature of the day was the British film of Gilbert and Sullivan’s

The first feature of the day was the British film of Gilbert and Sullivan’s  During production, Schertzinger reportedly received as many as 3,000 letters a week threatening “dire consequences” if he tampered unduly with the show’s sacred text. The letter-writers need not have worried; while the show was somewhat rearranged and several songs were cut to get the running time down to 90 minutes, the result was quite faithful to Gilbert and Sullivan’s satiric spirit. (And by the way, it was understood then, as it had been in 1885, that the butt of The Mikado‘s satire was Great Britain, not Japan.) In the New York Times, Frank S. Nugent called the movie “one of the most luscious productions of the operetta in history” (though he wondered if this purely theatrical piece was a good candidate for filming in the first place). Variety’s “Jolo” called it a “thoroughly ingratiating satire, carefully concocted.” The critics also praised the picture’s pastel Technicolor photography, which was justly nominated for an Academy Award (though of course this was 1939, and nothing was going to take that Oscar away from Gone With the Wind).

During production, Schertzinger reportedly received as many as 3,000 letters a week threatening “dire consequences” if he tampered unduly with the show’s sacred text. The letter-writers need not have worried; while the show was somewhat rearranged and several songs were cut to get the running time down to 90 minutes, the result was quite faithful to Gilbert and Sullivan’s satiric spirit. (And by the way, it was understood then, as it had been in 1885, that the butt of The Mikado‘s satire was Great Britain, not Japan.) In the New York Times, Frank S. Nugent called the movie “one of the most luscious productions of the operetta in history” (though he wondered if this purely theatrical piece was a good candidate for filming in the first place). Variety’s “Jolo” called it a “thoroughly ingratiating satire, carefully concocted.” The critics also praised the picture’s pastel Technicolor photography, which was justly nominated for an Academy Award (though of course this was 1939, and nothing was going to take that Oscar away from Gone With the Wind). After The Mikado came some comedy shorts from Hal Roach’s Lot of Fun bookending the lunch break. Before lunch it was

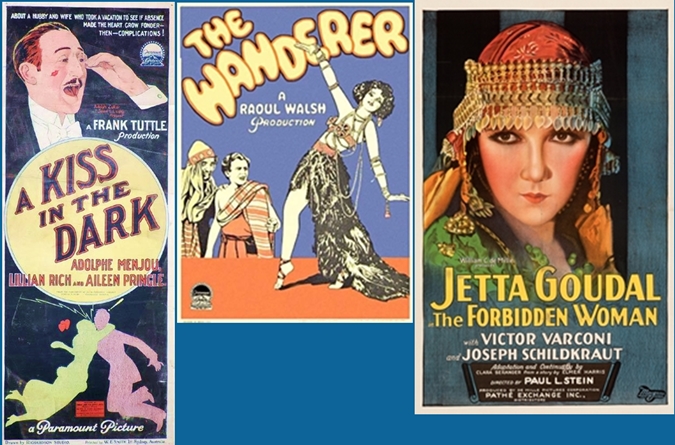

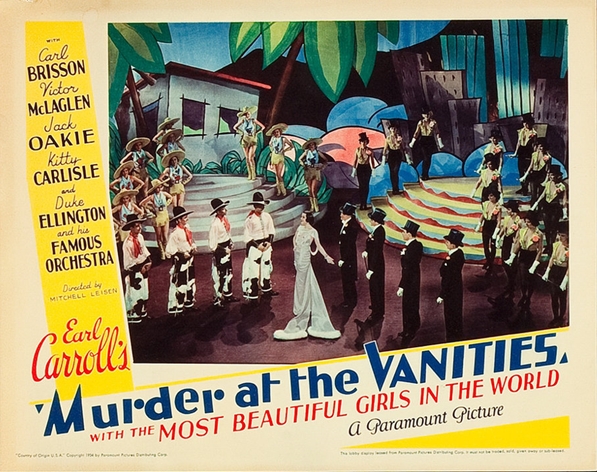

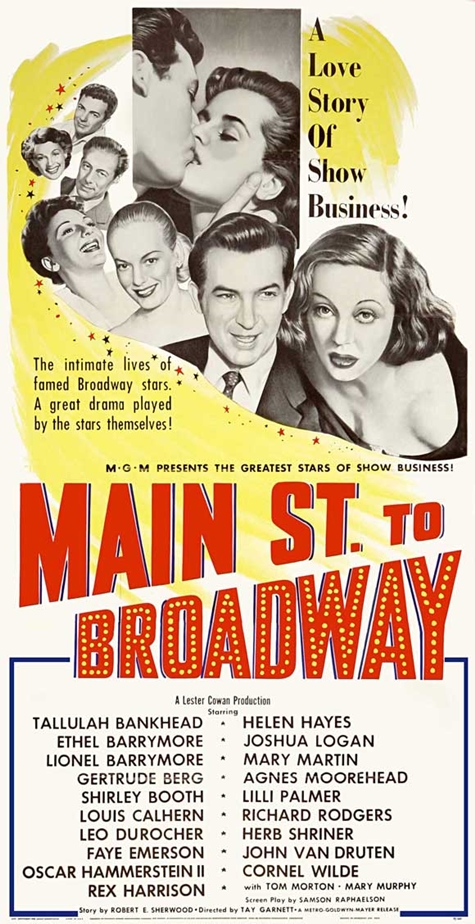

After The Mikado came some comedy shorts from Hal Roach’s Lot of Fun bookending the lunch break. Before lunch it was  Film musical historian and aficionado Richard Barrios hosted a “Vol. 2” session of

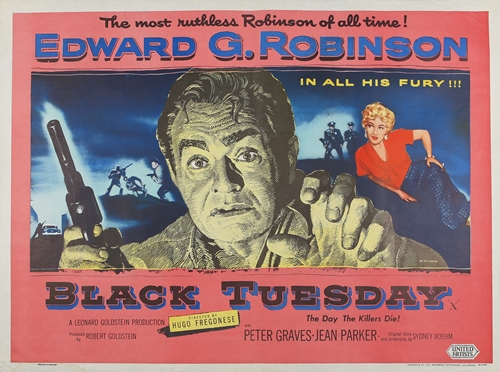

Film musical historian and aficionado Richard Barrios hosted a “Vol. 2” session of  When the lights came up after Main Street to Broadway, it was time for dinner. When we came back, it was to a presentation by biographer Alan K. Rode, author of

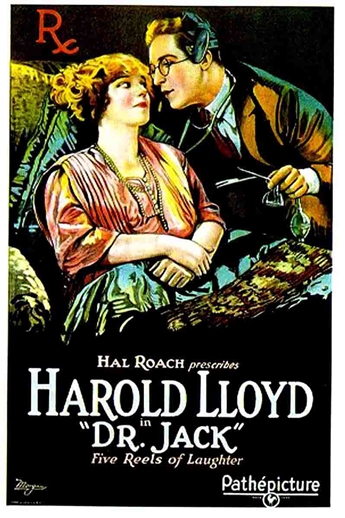

When the lights came up after Main Street to Broadway, it was time for dinner. When we came back, it was to a presentation by biographer Alan K. Rode, author of  Dr. Jack

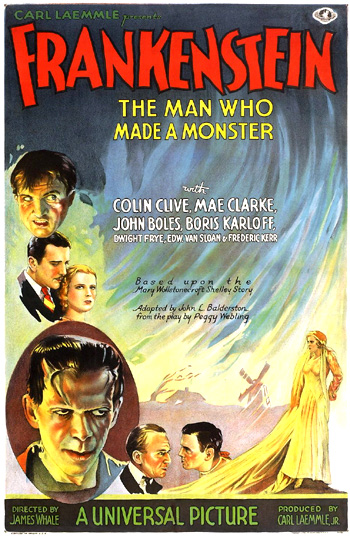

Dr. Jack  In keeping with Cinevent 52’s Halloween Weekend setting, Day 2 closed out with

In keeping with Cinevent 52’s Halloween Weekend setting, Day 2 closed out with  Cinevent, the venerable classic film convention that was a longtime fixture on Memorial Day Weekend in Columbus, Ohio, convened belatedly for the 52nd time October 28-31 this year. It was doubly belated, in fact — postponed from 2020 to 2021 by the COVID lockdown, then from May to October just to be on the safe side. Then this damned Delta Variant came along and seemed to threaten even that — but with vaccinations strongly encouraged and masks mandatory, the convention proceed as (re)scheduled.

Cinevent, the venerable classic film convention that was a longtime fixture on Memorial Day Weekend in Columbus, Ohio, convened belatedly for the 52nd time October 28-31 this year. It was doubly belated, in fact — postponed from 2020 to 2021 by the COVID lockdown, then from May to October just to be on the safe side. Then this damned Delta Variant came along and seemed to threaten even that — but with vaccinations strongly encouraged and masks mandatory, the convention proceed as (re)scheduled.  In the meantime, CMPS served as co-presenter of Cinevent 52, so let’s have a look at the program for this final year.

In the meantime, CMPS served as co-presenter of Cinevent 52, so let’s have a look at the program for this final year.

After the dinner break came the highlight of the day and one of the highlights of the whole weekend. This was

After the dinner break came the highlight of the day and one of the highlights of the whole weekend. This was  Then, just like that, it was back to melodrama for

Then, just like that, it was back to melodrama for