Thalberg called him “Worthless Willy.” This surely makes William Wyler the only recipient of the Academy’s Irving G. Thalberg Award to have been publicly disparaged by the man the award was named for.

Thalberg did have his reasons. Only three years older than Wyler, he was far beyond him in stature at Universal when Wyler started there as an errand boy in 1921. According to Wyler’s biographer Jan Herman, the only time Universal’s youthful production chief deigned to notice the 19-year-old Wyler, it didn’t go well for the future director. “You read German, don’t you?” Wyler, fairly fresh from Europe and still honing the command of English he’d begun developing there, said he did. Thalberg handed him a German novel, a property the studio was considering buying for director Erich von Stroheim. “Bring me a synopsis in English on Monday.”

This was on Friday, and Wyler didn’t make the deadline; he didn’t even finish the book. Monday came, then Tuesday and Wednesday before he could even tell Thalberg what the book was about; he appears never to have done a written synopsis. It also appears that Thalberg was administering a test — and Wyler flunked. In any case, Wyler — young and unfocused — never got another personal assignment, however trivial, from Thalberg. The “Worthless” moniker came along later, when Thalberg got wind of the teenager’s arrests for reckless driving; Thalberg must have decided the kid would never amount to much.

If so, then Thalberg, who died at 37, lived just long enough to get an inkling of how wrong he was. Even by the time Thalberg left Universal in 1924 for the new-minted super-studio MGM, Worthless Willy had already amounted to an assistant director — of sorts. On The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923), Thalberg’s pet project at Universal, Wyler was still just an errand boy, but now he was running errands for assistant directors Jack Sullivan and Jimmy Dugan, wrangling the picture’s thousands of extras and getting his first chance to wield the coveted megaphone.

The anecdote of the German novel is a telling one. He may have been a slow starter at Universal, and may have struck higher-ups — and in those days nearly everybody at Universal was higher up than he was — as a bad bet, but he was already showing a trait that would follow him all through his career: Willy Wyler didn’t like to be hurried. In time, the “Worthless Willy” nickname would give way to another: “90-Take Wyler.”

Bette Davis told a story about working with Wyler on Jezebel in the fall of 1937. Her first scene called for her to stride into her plantation home after dismounting from her horse and saucily slinging the long train of her riding outfit over her shoulder on her riding crop. At Wyler’s request, Davis had practiced long with the crop and felt ready to nail the scene in one take. In fact, she thought she did, but Wyler disagreed. He ordered another take, and another, and another. After a dozen takes, Davis, who had rarely required more than two takes in her entire career so far, was exasperated. “What do you want me to do differently?”

“I’ll know it when I see it.”

Whatever it was, Wyler saw it on the forty-eighth take. “Okay, that’s fine.” And he called a wrap for the day.

Davis was furious, and demanded to see the rushes of the day’s work. Wyler obliged. Davis no doubt was primed to fly into a self-righteous tirade: “What was wrong with that take…or that one…or that one?” But she never did. She walked into the screening room believing that she’d done the action exactly the same every single time, but now she saw that she hadn’t. Each take was different, and the forty-eighth was the best.

That’s how 90-Take Wyler operated, and in a way it wasn’t all that different from Worthless Willy. He knew what he wanted, but he wasn’t one of those directors — not always, anyway — who could get it from an actor with a few well-placed words. There’s a famous story about how Wyler’s friend John Huston, directing The African Queen, saved Katharine Hepburn from playing her character as a sour, prissy old-maid missionary (and probably saved the whole picture) by a simple, seemingly offhand remark comparing the character to Eleanor Roosevelt. Wyler didn’t work that way. There are countless stories of Wyler ordering another take, saying things like “It stinks.” “Do it again. Better.”

Charlton Heston on Ben-Hur, for example. One night, he said, Wyler came to him in his dressing room. “Chuck, you gotta be better in this picture.”

Nonplussed, Heston said, “Okay. What can I do?”

“I don’t know. I wish I did. If I knew, I’d tell you, and you’d do it, and that would be fine. But I don’t know.”

“That was very tough,” Heston recalled. “I spent a long time with a glass of scotch in my hand after that.”

Wyler, it seems, didn’t always issue instructions like a recipe to his actors. But he knew what he wanted. And he knew that “I’ll know it when I see it.”

These anecdotes conjure an image of a director passively waiting for lightning to strike, and willing to spend any amount of time and his producer’s money while he waited. What they don’t suggest is the process his refusal to accept the merely adequate sparked in his actors and writers. On their first picture together, The Big Country, Heston took exception to some minor piece of Wyler’s direction and wanted to discuss it. He didn’t have his script handy, so he asked to borrow Wyler’s.

Wyler always carried his script in a leather binder, with the titles of his movies engraved in gold inside the front cover; when he finished a picture, he’d take the script out, engrave that one’s title on the cover and move on to the next. As Heston took Wyler’s script, it flipped open to the inside cover and he saw the titles engraved there: Dodsworth, Dead End, Jezebel, Wuthering Heights, The Letter, The Westerner, The Little Foxes, Mrs. Miniver, The Best Years of Our Lives, The Heiress, Detective Story, Roman Holiday…

As Heston stared, Wyler grew impatient. “What is it, Chuck? What’s on your mind?”

Heston closed the script and handed it back. “Never mind, Willy. It’s not important.”

Wyler began directing on two- and five-reel westerns at Universal, where they didn’t want it good, they wanted it Thursday afternoon. The formulas were simple and unsubtle, and the movies had to move. Wyler showed, in now-forgotten titles like Ridin’ for Love, Gun Justice and Straight Shootin’, that he could turn it in Thursday afternoon and good. As the importance of his assignments increased, he drew on his bosses’ memory of how right he had gotten things before — under the gun, with the front office relentlessly beancounting — to take more time and money to get it exactly right this time. And as his reputation grew (and stayed with him nearly to the end) as a man who couldn’t make a flop, the people who worked with him tended more and more to take his word, like Heston on The Big Country and Ben-Hur. If Willy thinks I can do better, he must be right, and it’s up to me to figure out how.

When a director insists on take after take, saying nothing but “again” and “it stinks,” an actor’s response is usually to think (or say), “This guy’s giving me nothing, and he’s a tyrant to boot.” And some did. Jean Simmons worked for Wyler on The Big Country (1958), and even thirty years later she declined to discuss the experience with Jan Herman. Not so Sylvia Sidney, who dripped venom talking about doing Dead End fifty years after the fact. Ruth Chatterton didn’t wait that long; she was every inch the affronted diva on Dodsworth even as Wyler and producer Sam Goldwyn were trying to jumpstart her fading career (“Would you like me to leave the studio, Miss Chatterton?” “I would indeed, but unfortunately I’m afraid it can’t be arranged.”).

Whatever the truth of these situations, the point is what conspicuous exceptions Simmons, Sidney and Chatterton are among the legions of actors who worked with Wyler. The tales of his calling take after take are recounted with affection, not exasperation — not only by the Oscar winners, and not only years after wounded feelings have healed (Bette Davis got over her snit instantly). Wyler apparently never uttered the words “I know what I’m doing; trust me,” but that seems to be the effect he had on people. Combined with a powerful personal charm, he exuded an atmosphere of serene confidence on the set that made people want to please him, even as they struggled through twenty, thirty takes or more trying to figure out what the hell he wanted them to do. Wyler’s attitude was that they could do better; their response was to work all the harder to prove him right.

This is the intangible ingredient in Wyler’s pictures, along with the ones we can identify and point to: the bravura or simply spot-on-genuine performances, the incisive writing, the striking cinematography (Wyler worked seven times with the great Gregg Toland, and they brought out the best in each other), the handsome production designs. If you want to find the “personal element” in Wyler’s pictures, there it is: He had the confidence to take his time. In remarkably short order, thanks to luck as well as talent, he established a track record that allowed him to insist on it.

Gregory Peck nailed it exactly: “He was not one to talk a thing to death…What worked worked, and he knew how to recognize it…[N]ot all directors know how to do that. They pick the wrong take, or they’re not open to what can happen on the spur of the moment. Willy had a special sensitivity to that. He sensed the interplay between actors…This was ‘the Wyler touch.’ It’s why so many actors won Oscars with Willy, because he recognized the moments that brought them alive on the screen.”

I haven’t even gotten around to talking about Sam Goldwyn, have I? Next time, then; that testy, fruitful relationship deserves a post all to itself.

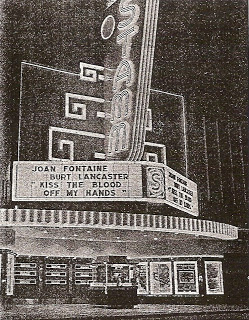

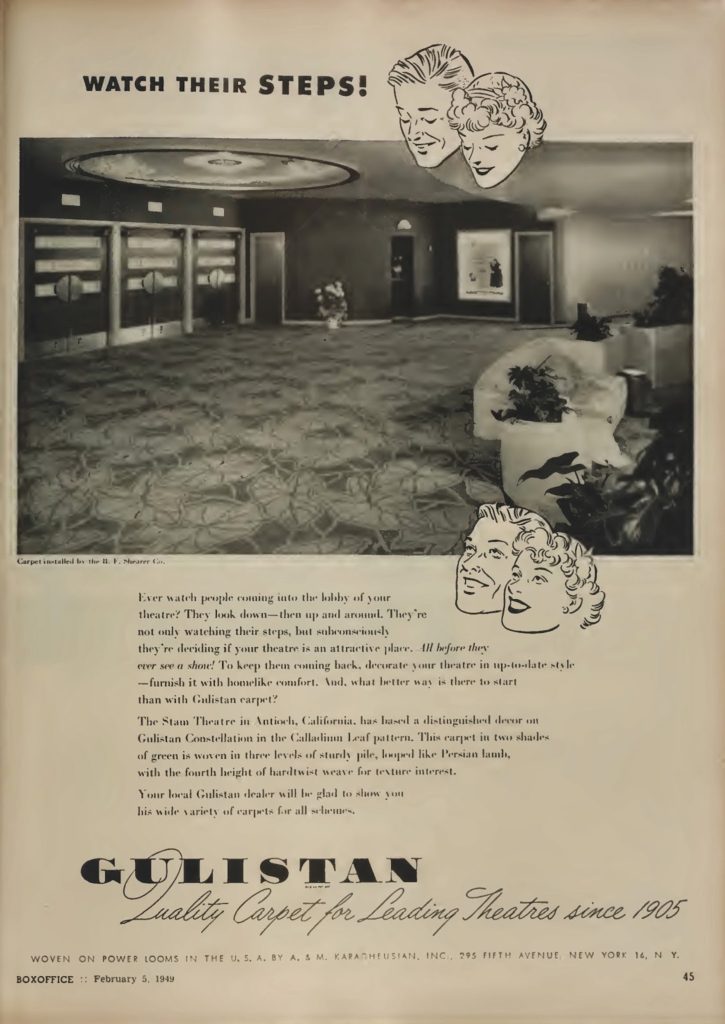

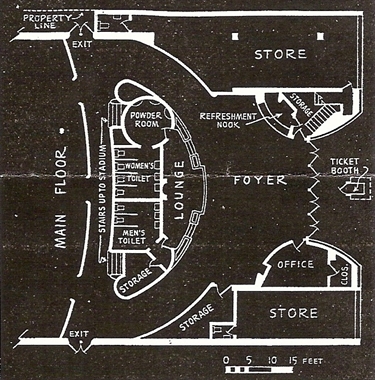

Here’s one of them, posted to Cinema Treasures by Prof. David Ducay. This shows the Stamm’s free-standing box office, which was removed (probably for security reasons) sometime in the late 1970s or early ’80s. You can see the menu board with admission prices hanging in the front window. What you can’t see to the right of that, lost in the glare, was one of the box office’s distinctive features: two clocks, one showing “Time Is Now,” the other showing “This Show Out” — telling you when the continuous show would cycle around to where you came in. Very convenient for parents dropping you off who wanted to know when to come back and get you. (I’ve often wondered if those two spring-driven clocks, each ticking away independently, ever drove the cashier nuts in that enclosed space.) The sign over the door behind the box office shows that the year is 1956, when King Vidor’s War and Peace was playing. Don’t know how I missed that one, but I did.

Here’s one of them, posted to Cinema Treasures by Prof. David Ducay. This shows the Stamm’s free-standing box office, which was removed (probably for security reasons) sometime in the late 1970s or early ’80s. You can see the menu board with admission prices hanging in the front window. What you can’t see to the right of that, lost in the glare, was one of the box office’s distinctive features: two clocks, one showing “Time Is Now,” the other showing “This Show Out” — telling you when the continuous show would cycle around to where you came in. Very convenient for parents dropping you off who wanted to know when to come back and get you. (I’ve often wondered if those two spring-driven clocks, each ticking away independently, ever drove the cashier nuts in that enclosed space.) The sign over the door behind the box office shows that the year is 1956, when King Vidor’s War and Peace was playing. Don’t know how I missed that one, but I did.

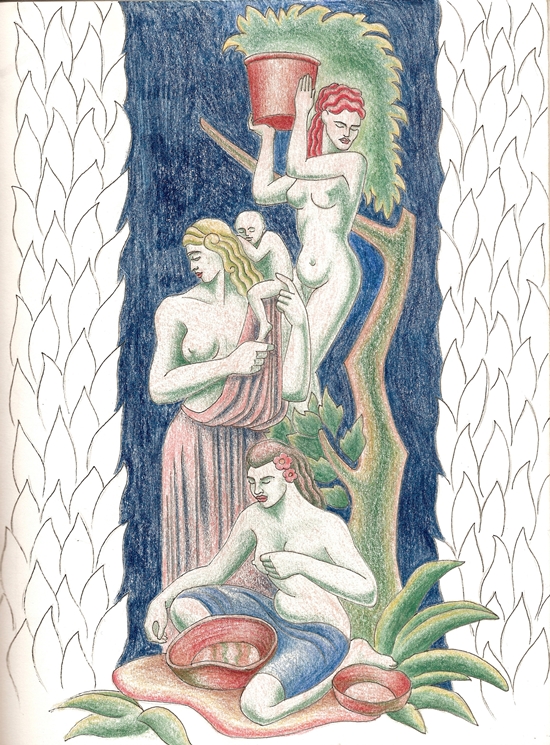

I have one more memento of the Stamm Theatre, shared with me by the artist, Gary Lee Parks of the THSA, and used here by permission. When Mr. Parks’s request to photograph the Stamm’s alfresco paintings was refused by the Stamm family, he did the next best thing. He bought an admission ticket, then sat in the audience with his sketchbook and pencil and copied one of the paintings in black and white, making color notes, which he turned into a full-color rendering as soon as he got home. (The movie he sat through, by the way, was The Coneheads; such dedication!) This painting can just barely be discerned as a dim smudge on the left side of the view above, the one facing the screen. I can vouch that Mr. Parks’s recreation is accurate; this painting remains particularly well-remembered by me — for obvious reasons (this was, after all, the 1950s). To tell the truth, the recollection of this picture glowing in the unearthly blacklight of that auditorium may have almost as much to do with my vivid memories of the Stamm as the movies I saw there.

I have one more memento of the Stamm Theatre, shared with me by the artist, Gary Lee Parks of the THSA, and used here by permission. When Mr. Parks’s request to photograph the Stamm’s alfresco paintings was refused by the Stamm family, he did the next best thing. He bought an admission ticket, then sat in the audience with his sketchbook and pencil and copied one of the paintings in black and white, making color notes, which he turned into a full-color rendering as soon as he got home. (The movie he sat through, by the way, was The Coneheads; such dedication!) This painting can just barely be discerned as a dim smudge on the left side of the view above, the one facing the screen. I can vouch that Mr. Parks’s recreation is accurate; this painting remains particularly well-remembered by me — for obvious reasons (this was, after all, the 1950s). To tell the truth, the recollection of this picture glowing in the unearthly blacklight of that auditorium may have almost as much to do with my vivid memories of the Stamm as the movies I saw there. Paradoxically, the El Campanil survives virtually intact (compare this recent photo with the 1930s postcard above). It is once again a multi-use performing arts center (just as it was when I was a 6-year-old tap dancer), saved from the wrecking ball by a citizens’ preservation drive in 2003.

Paradoxically, the El Campanil survives virtually intact (compare this recent photo with the 1930s postcard above). It is once again a multi-use performing arts center (just as it was when I was a 6-year-old tap dancer), saved from the wrecking ball by a citizens’ preservation drive in 2003.

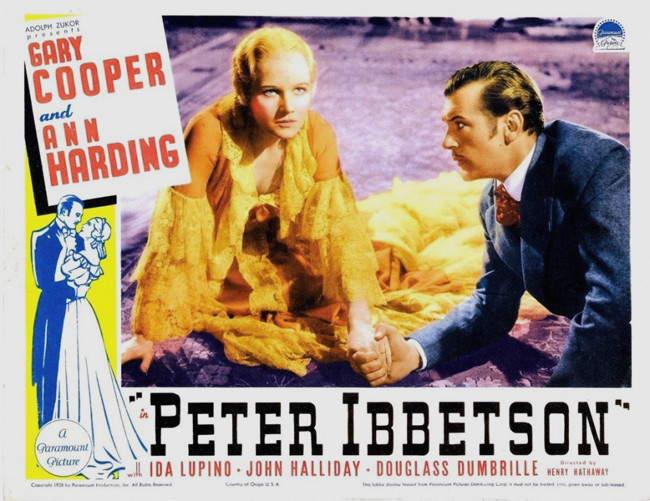

Every now and then in the 1930s (and more often than you might think) the Hollywood factory would turn out a picture that just didn’t fit the mold, one that seems in retrospect out of step with the reigning star system, the house style of its studio, the temper of the times — or a combination of all three. Lewis Milestone’s The General Died at Dawn was like that, and Warner Bros.’ Victorian-ornate A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and 1934’s Death Takes a Holiday. (For that matter, so was King Kong.) “Miracle pictures,” I call them; the fact that they’re as good as they are — that they were made at all — seems almost to violate the laws of Hollywood physics.

Every now and then in the 1930s (and more often than you might think) the Hollywood factory would turn out a picture that just didn’t fit the mold, one that seems in retrospect out of step with the reigning star system, the house style of its studio, the temper of the times — or a combination of all three. Lewis Milestone’s The General Died at Dawn was like that, and Warner Bros.’ Victorian-ornate A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and 1934’s Death Takes a Holiday. (For that matter, so was King Kong.) “Miracle pictures,” I call them; the fact that they’re as good as they are — that they were made at all — seems almost to violate the laws of Hollywood physics.

“You needn’t be afraid, Peter,” she says. “The strangest things are true, and the truest things are strange.”

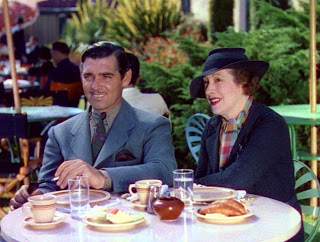

“You needn’t be afraid, Peter,” she says. “The strangest things are true, and the truest things are strange.” The look of the movie is as sublime as Cooper’s acting. If Lives of a Bengal Lancer shows what Hathaway learned from Victor Fleming, Ibbetson shows the effect of having worked with Josef von Sternberg. Hathaway and Lang modeled their lighting on Rembrandt (“He taught you not to be afraid of the dark.”), and the compositions reinforce the romantic yearnings of the story. See how often the two lovers are separated by iron bars, walls — even, as children, the rails of the cast-iron fence between their homes. When, in dreams, they walk through the bars to be together, it’s a simple trick that any amateur shutterbug could explain to you, but it’s so perfectly right that it takes your breath away.

The look of the movie is as sublime as Cooper’s acting. If Lives of a Bengal Lancer shows what Hathaway learned from Victor Fleming, Ibbetson shows the effect of having worked with Josef von Sternberg. Hathaway and Lang modeled their lighting on Rembrandt (“He taught you not to be afraid of the dark.”), and the compositions reinforce the romantic yearnings of the story. See how often the two lovers are separated by iron bars, walls — even, as children, the rails of the cast-iron fence between their homes. When, in dreams, they walk through the bars to be together, it’s a simple trick that any amateur shutterbug could explain to you, but it’s so perfectly right that it takes your breath away.