By the time Girl Crazy came to the screen again, Hollywood’s attitude toward musicals had changed diametrically, and with a will. A look at Clive Hirschhorn’s comprehensive coffee-table book The Hollywood Musical tells the tale: 10 musicals in 1932, when the first woebegone movie of Girl Crazy came out, versus 50 of them in 1942, the year MGM decided to do it again, and 75 in 1943, when MGM’s Girl Crazy was released. By now, musicals had become the jewels in Hollywood’s crown. Even Universal’s remake of The Phantom of the Opera had more opera and less phantom than the original silent version with Lon Chaney (sound gave Universal some wiggle room, and they decided to fill it with singing).

By the time Girl Crazy came to the screen again, Hollywood’s attitude toward musicals had changed diametrically, and with a will. A look at Clive Hirschhorn’s comprehensive coffee-table book The Hollywood Musical tells the tale: 10 musicals in 1932, when the first woebegone movie of Girl Crazy came out, versus 50 of them in 1942, the year MGM decided to do it again, and 75 in 1943, when MGM’s Girl Crazy was released. By now, musicals had become the jewels in Hollywood’s crown. Even Universal’s remake of The Phantom of the Opera had more opera and less phantom than the original silent version with Lon Chaney (sound gave Universal some wiggle room, and they decided to fill it with singing).

MGM bought the rights to Girl Crazy from RKO in 1939 at the behest of producer Jack Cummings. Cummings’s original idea was to remake the movie as a vehicle for Fred Astaire and Eleanor Powell, which presumably would have shifted the emphasis back to the songs and been more in keeping with the original show. Anyhow, nothing ever came of that, but Cummings held on to the property for several years. In the meantime, his MGM colleague Arthur Freed had produced a number of successful musicals, including three teaming Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland: Babes in Arms (’39), Strike Up the Band (’40) and Babes on Broadway (’41).

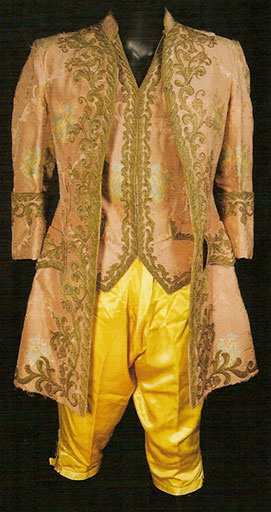

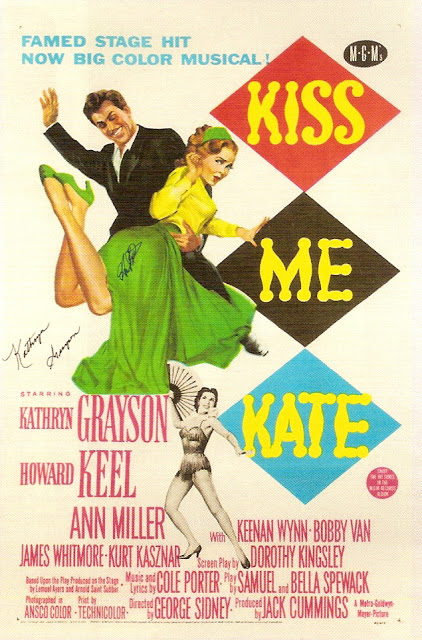

In mid-1942, Freed had designer-director John Murray Anderson, musical director Johnny Green, costumer Irene Sharaff and swimming starlet Esther Williams all under contract to develop a vehicle for Williams, but a workable script had never materialized and the project remained on a back burner. So Freed went to Cummings and proposed a swap: the whole Esther Williams package for the rights to Girl Crazy as a vehicle for Mickey and Judy. Cummings liked the idea, so did Louis B. Mayer, and the thing was done. (Cummings later produced Bathing Beauty, Esther Williams’s first starring picture.) Girl Crazy went into production in January 1943 with Busby Berkeley (who had directed the three previous Mickey-and-Judy musicals) directing.

Today, Arthur Freed is considered synonymous with “MGM musicals”, as if he were the only musical producer on the lot. Not so; there were also Cummings and Joe Pasternak (who had moved over from Universal, where he built his name on Deanna Durbin’s pictures), and both got their share of the glory at the time. Still, Freed’s unit was an awfully well-oiled machine, and Freed had a knack for attracting the best talent and getting the best out of it. His production of Girl Crazy reunited two men with a nostalgic stake in doing the thing right: Roger Edens and Georgie Stoll, both of whom had come far since their days in the orchestra pit of Girl Crazy on Broadway. (I wonder: Had Stoll and Edens seen RKO’s 1932 Girl Crazy and been appalled?) Now, Stoll would be credited as musical director on the picture; Edens’s credit reads “Musical Adaptation”, but that hardly scratches the surface of what Edens really did. As I said before, he was Freed’s right-hand man, much more than a “musical adaptor”, and on Girl Crazy he was virtually what would later be called a line producer — the guy actually on the set keeping an eye on things for the man in charge (i.e., Freed). And there was trouble almost immediately.

The first sequence Berkeley shot was the “I Got Rhythm” production number, which was originally planned to come about three-fourths of the way through the picture, and Edens didn’t like what he saw. “I’d written an arrangement of ‘I Got Rhythm’ for Judy,” Edens recalled, “and we disagreed basically about its presentation. I wanted it rhythmic and simply staged, but Berkeley got his big ensembles and trick cameras into it again, plus a lot of girls in Western outfits with fringed skirts and people cracking whips and firing guns all over my arrangement and Judy’s voice. Well, we shouted at each other and I said there wasn’t enough room on the lot for both of us.” (Edens exaggerated somewhat; there were no gunshots going off over Garland’s vocals. Otherwise, he has a point; the number begins to sound like the gunfight at the O.K. Corral.)

Berkeley’s working relationship with Judy Garland was unraveling as well. This was the fifth movie he directed her in — there had been For Me and My Gal (’42) in addition to the three with Rooney — and under his martinet bullying her attitude had gone from “I don’t know what I’d do without him” (on For Me and My Gal) to “I used to feel he had a big black bullwhip and was lashing me with it” (in conversation with Hedda Hopper, reported in Hopper’s autobiography). Judy was close to hysterics on the set of “I Got Rhythm”, her nervousness heightened by a stunt Berkeley designed in which she and Mickey were hoisted aloft by the ankles. The bit terrified Judy, just as a similar hoisting had when Berkeley put her through it in the “Minnie from Trinidad” number in Ziegfeld Girl (’40) — this time, making things worse for her, the bit was accompanied by dozens of pistols firing over and over again around her. After “I Got Rhythm” was in the can, Judy’s personal physician ordered her not to dance for three weeks.

To put the icing on the cake, Berkeley took nine days to shoot the number instead of the scheduled five, and he ran $60,000 over its budget.

So let’s recap: After less than two weeks, Girl Crazy was four days behind schedule and 60 grand over budget. Judy Garland was frazzled, Roger Edens was furious. Obviously, Berkeley had to go. Freed removed him from the picture and replaced him with Norman Taurog.

So let’s recap: After less than two weeks, Girl Crazy was four days behind schedule and 60 grand over budget. Judy Garland was frazzled, Roger Edens was furious. Obviously, Berkeley had to go. Freed removed him from the picture and replaced him with Norman Taurog.

The movie dispensed with all that nonsense about the $742.30 cab ride, but it still had playboy Danny Churchill (Rooney) making a spectacle of himself in New York. “Treat Me Rough” was the song used, performed by Tommy Dorsey’s band and sung by June Allyson. (Allyson was an MGM newcomer, simultaneously filming this one-shot while recreating her Broadway role in the studio’s movie of Best Foot Forward. By the time Girl Crazy was released, she had already made her splash in Best Foot Forward and was on her way to major stardom.)

This time, Danny’s a college student as well as a tycoon’s playboy son, and Dad (Henry O’Neill) cancels his return to Yale and sends him to his own alma mater “out west” (Cody College, the state unspecified). There, under the eye of Cody’s dean (Guy Kibbee), he is the usual fish out of water, smitten with the dean’s grandaughter, postmistress Ginger Gray (Judy). (I wonder: was the changing of the heroine’s first name a wink to Broadway’s original Molly, Ginger Rogers? How could it not be?)

From there Girl Crazy becomes a variation on the hey-kids-let’s-put-on-a-show formula that framed all the Mickey-and-Judy musicals, the variation this time being hey-kids-let’s-put-on-a-rodeo-and-save-the-school-from-closing. The plot is within hailing distance (just barely) of Bolton and McGowan’s original book, but it’s beside the point anyway, as it was on Broadway. In 1943, with Hollywood in general, and the Freed Unit at MGM in particular, operating at an all-time peak of efficiency and self-confidence, Girl Crazy was then what it remains today: an exhilarating series of musical highlights, one after another, bathing the screen in an embarrassment of riches. Clive Hirschhorn’s succinct appraisal is oft-quoted because it’s the plain truth: “Gershwin never had it so good.”

At the risk of becoming monotonous, let us count the ways. First, of course, is that rambunctious version of “Treat Me Rough”, which June Allyson invests with an innocent tomboy eroticism (she’s like a less obnoxious Betty Hutton) that must have had the Hays Office wondering if this sort of thing was really okay, then shrugging and deciding it was all just good clean fun after all.

At the risk of becoming monotonous, let us count the ways. First, of course, is that rambunctious version of “Treat Me Rough”, which June Allyson invests with an innocent tomboy eroticism (she’s like a less obnoxious Betty Hutton) that must have had the Hays Office wondering if this sort of thing was really okay, then shrugging and deciding it was all just good clean fun after all.

The quirky love-hate duet “Could You Use Me?” was something that Eddie Quillan and Arline Judge actually might have handled pretty well if RKO had deigned to include it in 1932. But they didn’t, and it was left to Mickey and Judy to bring it to the screen. Filmed in punishing 112-degree heat on location on a desert road outside Palm Springs (with pickup shots in the relative comfort of a soundstage back in Culver City), it’s a cheerful charmer in which Judy manages to suggest that Ginger’s resistance to Danny’s brash advances is already beginning to melt.

The quirky love-hate duet “Could You Use Me?” was something that Eddie Quillan and Arline Judge actually might have handled pretty well if RKO had deigned to include it in 1932. But they didn’t, and it was left to Mickey and Judy to bring it to the screen. Filmed in punishing 112-degree heat on location on a desert road outside Palm Springs (with pickup shots in the relative comfort of a soundstage back in Culver City), it’s a cheerful charmer in which Judy manages to suggest that Ginger’s resistance to Danny’s brash advances is already beginning to melt. “Embraceable You” is presented at a party for Ginger, in a scene that includes the movie’s only non-Gershwin interpolation: a chorus of “Happy Birthday to You” from Cody College’s assembled student body. Judy sings to the boys, then dances with them all, one by one and in groups, with an extended pas de deux with dance director Charles Walters. Later, after graduating to full direction himself, Walters helmed Judy in Easter Parade (’48), Summer Stock (’50), and her triumphant one-woman show at Broadway’s Palace Theatre in 1951.

“Embraceable You” is presented at a party for Ginger, in a scene that includes the movie’s only non-Gershwin interpolation: a chorus of “Happy Birthday to You” from Cody College’s assembled student body. Judy sings to the boys, then dances with them all, one by one and in groups, with an extended pas de deux with dance director Charles Walters. Later, after graduating to full direction himself, Walters helmed Judy in Easter Parade (’48), Summer Stock (’50), and her triumphant one-woman show at Broadway’s Palace Theatre in 1951. When Danny Churchill attends a party at the Governor’s Mansion to lobby against the closing of Cody, he meets up with his old pal Tommy Dorsey, and that sets the stage for a nifty piece of Big Band Era history: Tommy Dorsey and his Orchestra in a marvelous pop-concert rendition of “Fascinating Rhythm”. It’s a jumpin’ arrangement, and features a solo by “Danny Churchill” on piano. In fact, Mickey Rooney’s playing was dubbed by Arthur Schutt; still, as his keyboard fingering in the scene makes clear, Rooney was an accomplished pianist himself, and to the end of his days he spoke of the thrill of getting to perform “Fascinating Rhythm” with Dorsey and his band. (No doubt, even though the number had been prerecorded on MGM’s music stage, the band — including guest soloist Rooney — played for real on the set.)

When Danny Churchill attends a party at the Governor’s Mansion to lobby against the closing of Cody, he meets up with his old pal Tommy Dorsey, and that sets the stage for a nifty piece of Big Band Era history: Tommy Dorsey and his Orchestra in a marvelous pop-concert rendition of “Fascinating Rhythm”. It’s a jumpin’ arrangement, and features a solo by “Danny Churchill” on piano. In fact, Mickey Rooney’s playing was dubbed by Arthur Schutt; still, as his keyboard fingering in the scene makes clear, Rooney was an accomplished pianist himself, and to the end of his days he spoke of the thrill of getting to perform “Fascinating Rhythm” with Dorsey and his band. (No doubt, even though the number had been prerecorded on MGM’s music stage, the band — including guest soloist Rooney — played for real on the set.) That party leads to the inevitable misunderstanding when Ginger believes Danny has returned to his girl-crazy ways with the governor’s daughter (Frances Rafferty). It all gets sorted out in time for a happy ending, natch, but not before Judy Garland gets the opportunity — Hallelujah! — to redeem the tawdry vandalism of “But Not for Me” back in 1932. This is not only the high point of Girl Crazy — it’s the high point of Judy Garland’s entire career. With all due respect to “Over the Rainbow”, “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas”, “The Man That Got Away” or anything else you care to name, this is Judy’s best. Co-star Gil Stratton talked about watching the number being shot and said “it was something you ought to have paid admission to see.” The simplicity of Taurog’s staging, the delicate cinematography of William Daniels, and the combined artistry of Judy and and the Gershwin brothers all fuse into the kind of magic that the Hollywood of 1943 had led audiences to take for granted. Judy Garland was as good as it got, then or ever after, and here’s the proof.

That party leads to the inevitable misunderstanding when Ginger believes Danny has returned to his girl-crazy ways with the governor’s daughter (Frances Rafferty). It all gets sorted out in time for a happy ending, natch, but not before Judy Garland gets the opportunity — Hallelujah! — to redeem the tawdry vandalism of “But Not for Me” back in 1932. This is not only the high point of Girl Crazy — it’s the high point of Judy Garland’s entire career. With all due respect to “Over the Rainbow”, “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas”, “The Man That Got Away” or anything else you care to name, this is Judy’s best. Co-star Gil Stratton talked about watching the number being shot and said “it was something you ought to have paid admission to see.” The simplicity of Taurog’s staging, the delicate cinematography of William Daniels, and the combined artistry of Judy and and the Gershwin brothers all fuse into the kind of magic that the Hollywood of 1943 had led audiences to take for granted. Judy Garland was as good as it got, then or ever after, and here’s the proof. Originally, Girl Crazy was to end with a reprise of “Embraceable You”, Mickey and Judy surrounded by the rest of the cast as the orchestra swells up and out. But Busby Berkeley’s flamboyant staging of “I Got Rhythm”, scheduled to come almost 20 minutes before the end, threatened to turn anything that followed into a dribbling anticlimax. There was some hurried reshuffling of the script and music, and Girl Crazy as it was released on November 26 ended with “I Got Rhythm”. It must have positively galled Roger Edens; he’d gotten his way and had Berkeley canned from the picture, and now here was Berkeley literally getting the last word — cracking whips, blazing six-guns and all. But it was the right call, and, however grudgingly, Edens probably had to admit it.

Originally, Girl Crazy was to end with a reprise of “Embraceable You”, Mickey and Judy surrounded by the rest of the cast as the orchestra swells up and out. But Busby Berkeley’s flamboyant staging of “I Got Rhythm”, scheduled to come almost 20 minutes before the end, threatened to turn anything that followed into a dribbling anticlimax. There was some hurried reshuffling of the script and music, and Girl Crazy as it was released on November 26 ended with “I Got Rhythm”. It must have positively galled Roger Edens; he’d gotten his way and had Berkeley canned from the picture, and now here was Berkeley literally getting the last word — cracking whips, blazing six-guns and all. But it was the right call, and, however grudgingly, Edens probably had to admit it.

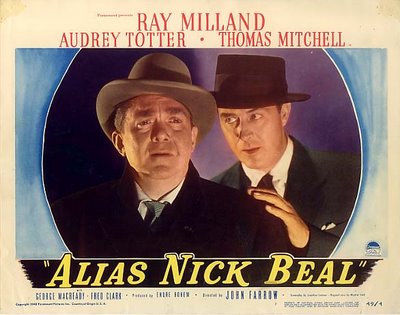

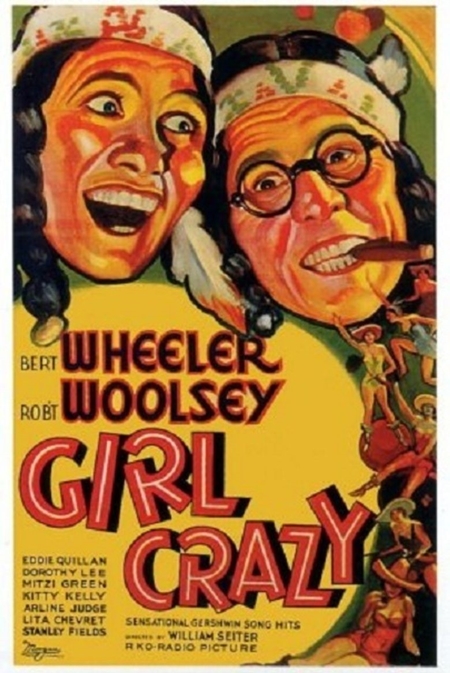

I have this fantasy in which I imagine that a scout from RKO Radio Pictures early in 1931 is told to go see Girl Crazy on Broadway and to report back about its potential as a movie. In his report, does he say, “The score is amazing; George and Ira Gershwin have written some songs that will be sung as long as singers sing”? Or “This Ethel Merman is dynamite; she electrifies an audience and she can put a song over like an artillery barrage”? Or “Ginger Rogers is a real charmer who has already shown that she photographs well; with care she could be groomed into a major star”? Does he say any of this? He does not. Instead, this brilliant showbiz oracle tells the front office, “This might make a good vehicle for Wheeler and Woolsey.”

I have this fantasy in which I imagine that a scout from RKO Radio Pictures early in 1931 is told to go see Girl Crazy on Broadway and to report back about its potential as a movie. In his report, does he say, “The score is amazing; George and Ira Gershwin have written some songs that will be sung as long as singers sing”? Or “This Ethel Merman is dynamite; she electrifies an audience and she can put a song over like an artillery barrage”? Or “Ginger Rogers is a real charmer who has already shown that she photographs well; with care she could be groomed into a major star”? Does he say any of this? He does not. Instead, this brilliant showbiz oracle tells the front office, “This might make a good vehicle for Wheeler and Woolsey.” Almost a third member of the (not really a) team was diminutive Dorothy Lee; she appeared in 16 of Wheeler and Woolsey’s pictures. A good physical match for Wheeler (he was five foot four, she five foot exactly), Lee served as a romantic partner for him, giving Wheeler (and the audience) a little relief from the obnoxious blowhard Woolsey. So it was in Girl Crazy, in which Wheeler took the role played on Broadway by Willie Howard (whose intransigence had killed the show before its time). The cabbie’s name was de-ethnicized from Gieber Goldfarb to Jimmy Deegan, the character was divested of the comic Yiddish persona that was Howard’s stock in trade, and Lee was brought in as Patsy, “the gal of the golden west”, to duet with Wheeler in one of only four musical numbers in the movie.

Almost a third member of the (not really a) team was diminutive Dorothy Lee; she appeared in 16 of Wheeler and Woolsey’s pictures. A good physical match for Wheeler (he was five foot four, she five foot exactly), Lee served as a romantic partner for him, giving Wheeler (and the audience) a little relief from the obnoxious blowhard Woolsey. So it was in Girl Crazy, in which Wheeler took the role played on Broadway by Willie Howard (whose intransigence had killed the show before its time). The cabbie’s name was de-ethnicized from Gieber Goldfarb to Jimmy Deegan, the character was divested of the comic Yiddish persona that was Howard’s stock in trade, and Lee was brought in as Patsy, “the gal of the golden west”, to duet with Wheeler in one of only four musical numbers in the movie.  Musicals, a novelty in the late ’20s, had worn out their welcome by 1932 and become a drug on the market; theater owners were known to reassure audiences in ads and posters that their current offering was “Not a Musical!” (The Big Revival over at Warner Bros. was still a year away.) In this atmosphere, no one at RKO was in a mood to look twice at the Gershwins’ songs in Girl Crazy. Instead, taking their cue from Willie Howard and William Kent having been the ones with star billing on Broadway, the studio jettisoned most of the score and refashioned the book — the weakest thing about the show — to suit their hot new team. So it is that in the movie, it isn’t Eddie Quillan’s Danny Churchill who takes a taxi from Manhattan to Arizona, it’s the gambler Slick (new surname: Foster) who hops into Jimmy Deegan’s cab for the trip out west. (The lady in the back seat with Woolsey is Kitty Kelly, playing what’s left of Ethel Merman’s role.) Two huge chunks of the picture’s modest 74-minute running time are eaten up by (1) Wheeler and Woolsey’s misadventures on the road to Arizona and (2) further misadventures later, when the action adjourns to Mexico.

Musicals, a novelty in the late ’20s, had worn out their welcome by 1932 and become a drug on the market; theater owners were known to reassure audiences in ads and posters that their current offering was “Not a Musical!” (The Big Revival over at Warner Bros. was still a year away.) In this atmosphere, no one at RKO was in a mood to look twice at the Gershwins’ songs in Girl Crazy. Instead, taking their cue from Willie Howard and William Kent having been the ones with star billing on Broadway, the studio jettisoned most of the score and refashioned the book — the weakest thing about the show — to suit their hot new team. So it is that in the movie, it isn’t Eddie Quillan’s Danny Churchill who takes a taxi from Manhattan to Arizona, it’s the gambler Slick (new surname: Foster) who hops into Jimmy Deegan’s cab for the trip out west. (The lady in the back seat with Woolsey is Kitty Kelly, playing what’s left of Ethel Merman’s role.) Two huge chunks of the picture’s modest 74-minute running time are eaten up by (1) Wheeler and Woolsey’s misadventures on the road to Arizona and (2) further misadventures later, when the action adjourns to Mexico.  As for those four songs, only three were from the show. The movie opens promisingly with an amusing, if abbreviated, rendition of “Bidin’ My Time”, with four singing cowboys moseyin’ along on the back of the same overburdened horse, while the camera moves through the Custerville cemetery from the grave of one luckless sheriff to the next, and the next.

As for those four songs, only three were from the show. The movie opens promisingly with an amusing, if abbreviated, rendition of “Bidin’ My Time”, with four singing cowboys moseyin’ along on the back of the same overburdened horse, while the camera moves through the Custerville cemetery from the grave of one luckless sheriff to the next, and the next. A few minutes later comes “You’ve Got What Gets Me” a new song by George and Ira written for the movie. (In point of fact, it wasn’t entirely new; it was a reworking of another song, “Your Eyes, Your Smile”, which had been cut from the Broadway production of Funny Face before it opened in 1927.) This is a light romantic duet between Wheeler and Dorothy Lee (already, as noted, a staple of their pictures together), followed by a sprightly tap dance in which they’re joined by little Mitzi Green as Wheeler’s pesky sister. Toward the end of her life, Dorothy Lee remembered Girl Crazy with bitter disgust as the movie where they photographed her behind a post (“I saw it once,” she said. “I couldn’t look at it again.”), and this frame from the dance shows she wasn’t being hypersensitive — you can just about make out her elbows (she’s dancing to the left of Wheeler). Why would anybody bother to stage a tap dance on a set dominated by an enormous vine-covered wishing well right in the middle of the floor (and seemingly taking up half of it)? It’s hard to comprehend — but then, the songs simply weren’t a priority.

A few minutes later comes “You’ve Got What Gets Me” a new song by George and Ira written for the movie. (In point of fact, it wasn’t entirely new; it was a reworking of another song, “Your Eyes, Your Smile”, which had been cut from the Broadway production of Funny Face before it opened in 1927.) This is a light romantic duet between Wheeler and Dorothy Lee (already, as noted, a staple of their pictures together), followed by a sprightly tap dance in which they’re joined by little Mitzi Green as Wheeler’s pesky sister. Toward the end of her life, Dorothy Lee remembered Girl Crazy with bitter disgust as the movie where they photographed her behind a post (“I saw it once,” she said. “I couldn’t look at it again.”), and this frame from the dance shows she wasn’t being hypersensitive — you can just about make out her elbows (she’s dancing to the left of Wheeler). Why would anybody bother to stage a tap dance on a set dominated by an enormous vine-covered wishing well right in the middle of the floor (and seemingly taking up half of it)? It’s hard to comprehend — but then, the songs simply weren’t a priority.  But, with all due sympathy to Ms. Lee, that’s not the worst. The absolute nadir of RKO’s Girl Crazy — lower than any of Wheeler and Woolsey’s comedy, already too low by half — comes with the disgraceful treatment accorded “But Not for Me”. What on Broadway had been a wistful solo of lost love by Ginger Rogers was revamped as a trio for Eddie Quillan as Danny, Arline Judge as Molly, and Mitzi Green trying to patch things up between them. Ira’s lyric was twisted around to say the exact opposite of what he wrote (“Beatrice Fairfax, don’t you dare/Ever tell me he won’t care…”), and George’s tempo was sped up until the song sounded like the merry-go-round gone wild in Strangers on a Train. Quillan and Judge were hardly singers (which may explain the breakneck tempo, always easier for non-singers to handle), and they rush through the song as if they have to be someplace; Quillan darts off-camera before the music even tinkles to a stop. The song comes off like a playground argument between two petulant kids. It’s followed by a reprise in which Green tries to cheer Judge up by using the song to do impressions (and pretty good ones, too) of Bing Crosby, Roscoe Ates, George Arliss and Edna May Oliver. This plays oddly today, especially with audiences who never heard of Ates, Arliss or Oliver, but at least it had a counterpart in the original show: Willie Howard was famous for his impressions, and the book incorporated them by having the cabbie try to cheer Ginger Rogers’ Molly with a reprise a la Rudy Vallee and Maurice Chevalier — but only after Ginger had already given the song its full soulful due. This movie never bothers to do that.

But, with all due sympathy to Ms. Lee, that’s not the worst. The absolute nadir of RKO’s Girl Crazy — lower than any of Wheeler and Woolsey’s comedy, already too low by half — comes with the disgraceful treatment accorded “But Not for Me”. What on Broadway had been a wistful solo of lost love by Ginger Rogers was revamped as a trio for Eddie Quillan as Danny, Arline Judge as Molly, and Mitzi Green trying to patch things up between them. Ira’s lyric was twisted around to say the exact opposite of what he wrote (“Beatrice Fairfax, don’t you dare/Ever tell me he won’t care…”), and George’s tempo was sped up until the song sounded like the merry-go-round gone wild in Strangers on a Train. Quillan and Judge were hardly singers (which may explain the breakneck tempo, always easier for non-singers to handle), and they rush through the song as if they have to be someplace; Quillan darts off-camera before the music even tinkles to a stop. The song comes off like a playground argument between two petulant kids. It’s followed by a reprise in which Green tries to cheer Judge up by using the song to do impressions (and pretty good ones, too) of Bing Crosby, Roscoe Ates, George Arliss and Edna May Oliver. This plays oddly today, especially with audiences who never heard of Ates, Arliss or Oliver, but at least it had a counterpart in the original show: Willie Howard was famous for his impressions, and the book incorporated them by having the cabbie try to cheer Ginger Rogers’ Molly with a reprise a la Rudy Vallee and Maurice Chevalier — but only after Ginger had already given the song its full soulful due. This movie never bothers to do that. The following year would come the game-changer: Warner Bros. (and Busby Berkeley) with the spectacular hat trick of 42nd Street, Gold Diggers of 1933 and Footlight Parade to put musicals back in vogue again, where they would remain for decades — even Poverty Row studios like Republic, Monogram and PRC would regularly try their hands at them. But all that came too late to help RKO’s Girl Crazy. It was born before its time; the studio didn’t appreciate the property it had, and didn’t have the wit, confidence or foresight to do what should have been done with it.

The following year would come the game-changer: Warner Bros. (and Busby Berkeley) with the spectacular hat trick of 42nd Street, Gold Diggers of 1933 and Footlight Parade to put musicals back in vogue again, where they would remain for decades — even Poverty Row studios like Republic, Monogram and PRC would regularly try their hands at them. But all that came too late to help RKO’s Girl Crazy. It was born before its time; the studio didn’t appreciate the property it had, and didn’t have the wit, confidence or foresight to do what should have been done with it. This post has grown in the planning, to the point where I’m putting it up in two parts (maybe more; we’ll see how things shake out). I have an epic tale to tell, nothing less than the rise and fall of the Hollywood musical, as reflected in the screen career of a single property: Girl Crazy, the 1930 Broadway hit with songs by George and Ira Gershwin, book by Guy Bolton and John McGowan.

This post has grown in the planning, to the point where I’m putting it up in two parts (maybe more; we’ll see how things shake out). I have an epic tale to tell, nothing less than the rise and fall of the Hollywood musical, as reflected in the screen career of a single property: Girl Crazy, the 1930 Broadway hit with songs by George and Ira Gershwin, book by Guy Bolton and John McGowan. Merman’s debut alone was enough to make Girl Crazy‘s opening a Broadway landmark, but there was more. Others present that night wouldn’t make it big until later, but the fact that they were there at all is enough to make you pray for time travel. For starters, there was the man who put together the pit orchestra: Ernest Loring “Red” Nichols, age 25, one of the busiest musicians in town. He was an accomplished cornetist who could play equally well “hot” and “straight”, and he had already made hundreds of Dixieland recordings for Brunswick Records, usually with an ad hoc band billed as Red Nichols and his Five Pennies.

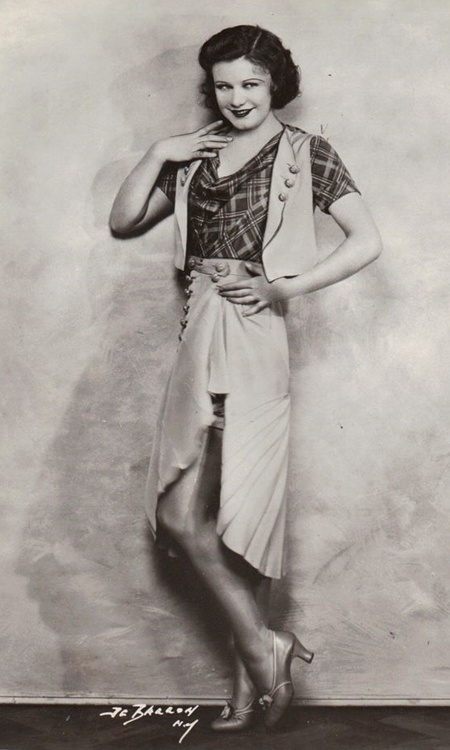

Merman’s debut alone was enough to make Girl Crazy‘s opening a Broadway landmark, but there was more. Others present that night wouldn’t make it big until later, but the fact that they were there at all is enough to make you pray for time travel. For starters, there was the man who put together the pit orchestra: Ernest Loring “Red” Nichols, age 25, one of the busiest musicians in town. He was an accomplished cornetist who could play equally well “hot” and “straight”, and he had already made hundreds of Dixieland recordings for Brunswick Records, usually with an ad hoc band billed as Red Nichols and his Five Pennies. Playing Girl Crazy‘s lead was 19-year-old Ginger Rogers, fresh from making her Broadway debut in Top Speed and creating a sensation purring “Cigarette me, big boy” in her first movie, Young Man of Manhattan. She had two of Girl Crazy‘s most enduring songs, “Embraceable You” and “But Not for Me”, and by all accounts handled them quite nicely. But lacking what Cole Porter later called Ethel Merman’s “golden foghorn” voice, she had to stand helplessly by while Ethel stole her thunder night after night; it would take the intimacy of the movie camera to coax her star into full bloom. (And here’s a fun fact: During rehearsals one of her dance numbers was not working exactly right, so producers Alex A. Aarons and Vinton Freedley asked a dancing star they knew to step in and refine the choreography as a favor, and he coached Ginger on the routine in the lobby of the Alvin during rehearsals. You guessed it: It was Fred Astaire.)

Playing Girl Crazy‘s lead was 19-year-old Ginger Rogers, fresh from making her Broadway debut in Top Speed and creating a sensation purring “Cigarette me, big boy” in her first movie, Young Man of Manhattan. She had two of Girl Crazy‘s most enduring songs, “Embraceable You” and “But Not for Me”, and by all accounts handled them quite nicely. But lacking what Cole Porter later called Ethel Merman’s “golden foghorn” voice, she had to stand helplessly by while Ethel stole her thunder night after night; it would take the intimacy of the movie camera to coax her star into full bloom. (And here’s a fun fact: During rehearsals one of her dance numbers was not working exactly right, so producers Alex A. Aarons and Vinton Freedley asked a dancing star they knew to step in and refine the choreography as a favor, and he coached Ginger on the routine in the lobby of the Alvin during rehearsals. You guessed it: It was Fred Astaire.) Act II finds half the population of Custerville in San Luz. Danny finds Molly, bids her farewell and wishes her all the best with Sam; only after he leaves does she realize her true feelings for him, and now she fears the knowledge has come too late. But when she learns that Sam has registered them at the local hotel as husband and wife, she realizes what a cad he is and runs to Danny’s arms. Outraged, Danny blurts a threat against Sam that returns to bite him when Sam is assaulted and robbed and Danny is accused of the crime. Meanwhile, Kate confronts her cheating husband. Eventually — jeez, let’s cut to the chase — Gieber exposes Lank and his henchman Pete as the men who robbed Sam, Kate and Slick reconcile, Danny and Molly are reunited, and everybody presumably lives happily ever after back in Custerville.

Act II finds half the population of Custerville in San Luz. Danny finds Molly, bids her farewell and wishes her all the best with Sam; only after he leaves does she realize her true feelings for him, and now she fears the knowledge has come too late. But when she learns that Sam has registered them at the local hotel as husband and wife, she realizes what a cad he is and runs to Danny’s arms. Outraged, Danny blurts a threat against Sam that returns to bite him when Sam is assaulted and robbed and Danny is accused of the crime. Meanwhile, Kate confronts her cheating husband. Eventually — jeez, let’s cut to the chase — Gieber exposes Lank and his henchman Pete as the men who robbed Sam, Kate and Slick reconcile, Danny and Molly are reunited, and everybody presumably lives happily ever after back in Custerville.