July 1 will mark the 110th anniversary of the birth of William Wyler (1902-81), peerless movie director par excellence

. The occasion is being observed by a blogathon hosted by The Movie Projector June 24 – 29, in which many of my fellow members in the Classic Movie Blog Association (CMBA) will be holding forth on their favorite Wyler pictures. Go here for a list of blogathon participants and links to their individual posts as they go up.

For my part, in conjunction with The Movie Projector’s blogathon, I’m republishing a series of five posts I did on Wyler in 2010, one a day for five of the six days of the blogathon. Happy Birthday, Willy, and thanks for the memories!

* * *

When William Wyler died in 1981, writer-director Philip Dunne delivered a euolgy at a memorial service in a packed auditorium at the Directors Guild of America. “Talent,” he said, “doesn’t care whom it happens to. Sometimes it happens to rather dreadful people. In Willy’s case, it happened to the best of us.”

Everybody called him Willy. Naturally enough — it was his name. He was born Willi Wyler, actually, in Alsace on July 1, 1902. When he began directing two-reel westerns for Universal in 1925, they Anglicized — and, to their minds, dignified — his given name to William, and he went along, but he never changed it legally, and to his friends and family he was Willy to the end.

He looks more like a Willy here, on the left holding the megaphone, playing a Hitchcockian cameo as the assisstant director of the movie-within-the-movie in Daze of the West, his last two-reeler for Universal; he had already begun directing five-reel westerns and would soon graduate to more prestigious (for Universal, anyhow) features. He’s 25 in this picture and has already been directing for two years, the youngest on the Universal lot and probably the youngest in Hollywood. (A few years later, he took mild umbrage at seeing Mervyn LeRoy over at Warners touted as Hollywood’s youngest — “He had press agents and I didn’t.” — even though LeRoy was two years older and began directing two years later. Much later on, coincidentally, both would work for producer Sam Zimbalist on the two huge Roman epics that bookended the 1950s at MGM: LeRoy on Quo Vadis and Wyler on Ben-Hur.)

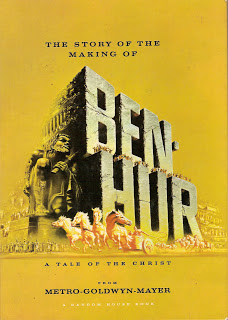

In between the one-week shoot on Daze of the West and the eight months on Ben-Hur, Wyler had one helluva run. In the end it may have been Ben-Hur that proved the undoing of his reputation, at least among “serious” film students. Wyler certainly thought so: “Cahiers du Cinema never forgave me for the picture. I was completely written off as a serious director by the avant-garde, which had considered me a favorite for years. I had prostituted myself.”

Well, it certainly didn’t seem that way at the time. At least among the hoi polloi and mainstream movie reviewers, Ben-Hur looked like Wyler’s masterpiece; his Oscar for directing it was only one of the eleven it won, a record that stood for 37 years. In 1959 and ’60, Ben-Hur wasn’t simply a great movie, it was a touchstone in the march of human culture. It was everywhere; you couldn’t catch a cold without blowing your nose on Ben-Hur kleenex, and everybody who even wanted to be anybody simply had to see it.

In time cooler heads prevailed, and it became clear that as great movies and cultural touchstones go, Ben-Hur was neither. But by then the damage was done; the avant-garde (whoever they are) had abandoned Wyler for — oh, pick a name: Howard Hawks? Vincente Minnelli? John Cassavetes, Nicholas Ray, Samuel Fuller? Andrew Sarris’s American Cinema relegated Wyler to four tiers below the Pantheon, in a section headed “Less Than Meets the Eye”. David Thomson’s Biographical Dictionary of Film dismissed him as “Hollywood’s idea of an outstanding director.”

True, it’s hard to believe that the director of the bloated, lumbering Ben-Hur is the same man, 20-plus years on, who turned out the spare, gritty Hell’s Heroes or the trifling, light-hearted confection The Good Fairy with Margaret Sullavan (who became, for a scant sixteen months, his first wife), never mind anything in between. Wyler’s career doesn’t have to stand on Ben-Hur, nor does it deserve to fall on it.

I have an idea for a book, and I may yet do it: The Movie Directors’ Hall of Fame. The idea is this: create a scoring system for directors, compiling statistics the way they do for professional athletes. Award so many points for winning an Oscar, so many for directing an Oscar-winning best picture, for directing an Oscar-winning or nominated performance, for directing one of the top box-office movies of the year, for winning the DGA or other directing awards, and so on. Total up the points and see how things shake out.

Now clearly, a scoring system where, for example, Kevin Costner beats out Orson Welles isn’t going to be definitive. But let’s take it as a premise, just for the sake of argument — something at least a bit more objective than asking an assortment of critics and “film industry professionals” what they think are the greatest movies of all time. The stats pretty much speak for themselves: William Wyler is the Babe Ruth, the Wilt Chamberlain, the Muhammad Ali of movie directors. There isn’t even a close second.

Wyler won three Academy Awards for best director. Only one director (Frank Capra) has won as many, and only one other (John Ford) has won more. Perhaps more important, all three of Wyler’s movies also won best picture; one of Capra’s didn’t, and only one of Ford’s did.

Wyler was nominated for best director a total of twelve times; his nearest competitor is Billy Wilder, with eight. Wilder’s nominations spanned 17 years, from 1944 to 1960, which could indicate a hot streak, while Wyler’s ran 30 years, ’36 to ’65, which you could read as a sustained career. Fred Zinnemann has seven nominations, several have six, and quite a few have five. But a full dozen? Only Wyler, and it’s all but inconceivable that any director will ever top his total (or Wilder’s, for that matter).

But where Wyler’s directorial touch really shows is in the number of actors and actresses who won or were nominated for his films: 14 wins (or 13½, if you insist; one of them, Walter Brennan’s supporting win for Come and Get It, was for a film where Wyler shared director credit, taking over after producer Sam Goldwyn fired Howard Hawks) and a whopping 36 nominations. His closest runner-up here is Elia Kazan, with nine wins and 24 nominations. It’s particularly telling to note the unusual number of times that two performers won for the same Wyler picture: Jezebel, Mrs. Miniver, The Best Years of Our Lives, Ben-Hur. Multiple nominations, too: two for Dodsworth, Jezebel, Wuthering Heights, The Letter and others; three for The Little Foxes, and five for Mrs. Miniver.

Surely this record will stand for as long as Oscars continue to be handed out. Today the only director working with anything like the prolificacy of Golden Age Hollywood is Woody Allen — 41 features in 43 years — and he’s only racked up six acting wins and 16 nominations (including his own). How long would it take Steven Spielberg or James Cameron — or even Martin Scorsese (five wins, 20 nominations) — to equal Wyler’s tally? In a Hollywood where directors devote two, three, four years to one picture, it can’t be done.

In Part 2, I’ll look a little closer at some of these pictures, at Wyler’s productive partnership with Samuel Goldwyn, and the working style with which Wyler often drove his actors nuts, even as he shepherded so many of them to the podium on Oscar night.

The following comment from Grand Old Movies was inadvertently deleted:

"I've never understood the Auteur Pantheon, and the 'tiers' into which its devising critics slotted directors. If a picture's good, it's good; does it matter if the director is Pantheon or Non-Pan? It seems an unusually rigid way of looking at movies (and also seeing greatness in films that really don't have it). And why deny Wyler Pantheon status just because of one film that doesn't fit into what's considered trendy? Thanks for reprinting your great series on Wyler's career; it gives wonderful insights into his work."

Thank you, GOM, for the comment, and apologies for accidentally discarding it!

First, let me say that I like Ben-Hur a lot. Second, I agree that Wyler deserves to be regarded as one of the best directors ever. Look forward to reading Part II.

Thanks, all! More to come. Ken A., I hope you're checking out all the posts on the blogathon; a lot of good ground covered there, about movies I hope you'll catch up with one of these days.

R.D., interesting point that Wyler never really worked in film noir; hadn't thought about it, but you're right. Still, his work on pictures like Dead End, Detective Story and The Desperate Hours suggest that he'd have acquitted himself well in that genre too, if he'd had a mind to.