Continuing with

London After Midnight by Marie Coolidge-Rask:

Chapter 10 – A Question of Vampires

The howling of the dog, coming from the direction of Balfour House, continues as Sir James and Yates make their way home from the crypt. They recount their experience to Hibbs, and the three discuss aspects of vampire lore as written in Colonel Yates’s book. Since murdered men and suicides are supposedly liable to become vampires, and since Roger Balfour’s coffin was still undisturbed at the time of Harry’s interment, it is cautiously suggested that the son’s unsolved murder may have had some supernatural effect on Roger Balfour’s restless soul. Sir James is clearly rattled by the night’s experience; Hibbs and Yates realize that there is some unknown factor at work over in Balfour House, and the mystery seems to deepen with every new event. It is near dawn when Sir James and Colonel Yates go to bed. Hibbs steals back downstairs to the library for further study of Colonel Yates’s book.

Chapter 11 – Harrowing Tales

All three men rise late the next day, leaving Lucy feeling quite lonely in the house, oppressed in the heat that has been intensified, rather than dispelled, by the early-morning electrical storm. At dinner that evening, conversation is kept trivial; by tacit agreement among the three men, Lucy is given no hint of what happened the night before.

Later that night, after Lucy has gone to her room, the three men resume their discussion of the night before. Suddenly they hear a piercing scream from upstairs, in the direction of Lucy’s room. Rushing upstairs, they find Lucy’s door locked. They try to break down the door, but before they have to, the door opens. In the room they find Smithson, the maid, trembling and sobbing, her eyes wide with fear, two small wounds at her throat, similar to the ones seen on the body of Harry Balfour. Sobbing, she tells the men that Lucy is locked in her dressing room, and they release the confused and frightened young lady from her confinement.

Finally, Smithson pulls herself together and tells the men what happened. As Miss Lucy was getting ready for bed, she says, she left her to fetch some towels from the linen closet. In the hallway she saw the man in the beaver hat, the one she saw on the steps of Balfour House as she was passing the night before. The man was stooped over and creeping toward her, his skeletal hand outstretched, his spiky teeth gleaming. Smithson was too frightened even to scream.

Thinking of Miss Lucy, Smithson says, she rushed back to the young lady’s room, shoved Lucy into the dressing room and locked her in. Then she locked the door to the outer room and thought they were safe. But before her horrified eyes, a green mist streamed through the keyhole and formed itself into the man in the beaver hat. The man came to her; she was unable to speak or scream, or even move. She felt him bending over her, felt his teeth on his throat. That must have been when she screamed, she says, but she doesn’t remember it. She knew nothing more until she heard Sir James, Colonel Yates and Hibbs pounding at the still-locked door.

Lucy, greatly excited, calls their attention to the window, where all of them see the man in the beaver hat skulking across the grounds in the direction of Balfour House. Colonel Yates tells Hibbs to remain with Lucy and see that she is not left alone; he and Sir James will investigate the matter further.

Chapter 12 – Panic

Left alone with Lucy and Hibbs, Smithson realizes that the two young people (whose feelings for each other have not escaped her notice) wish to be alone, so she tells them she is going down to the kitchen; after her experience she could use a nice cup of hot tea. Downstairs she finds the servants — butler, housekeeper, cook, maids and footmen — cowering in the kitchen, wondering about all the commotion earlier but afraid to go and see what it was. They mill around her, clamoring for news. Deciding she could use something a little stronger than tea, Smithson asks Billings, the butler, for “a little drop of spirits.” Thus fortified, she proceeds to regale the servants with another recounting of her experience in Lucy’s room, this one much embellished for dramatic effect as Smithson relishes the attentions of her rapt and horrified audience. At this inopportune moment, a cat knocks over a tin pan from the sink onto the floor; the sudden clatter sends the servants into an uproar. Upstairs, Lucy and Hibbs hear the melee downstairs and wonder what can possibly happen next.

Chapter 13 – The Woman on the Ceiling

Colonel Yates and Sir James make their way to Balfour House, proceeding slowly by a roundabout route, pausing frequently to watch and listen for prowlers or anything untoward. Once again Sir James’s heart is racing, and once again he depends entirely on the resoluteness of Colonel Yates to keep him going.

It is well after midnight when they approach Balfour House. The house is dark, but they can see a faint light glimmering from one of the upper windows — in fact from the “secret chamber” that has been unoccupied for centuries, the one in which a woman’s ghost is said to roam. Slowly forcing their way through the tangled grass and foliage of the overgrown grounds, they find a large tree from which they should be able to see into the lighted chamber. Taking the lead as usual, Yates climbs into the tree. At that moment they hear, low but clearly audible, the insistent sobbing of a woman in despair.

Through the high windows of the secret room they can see only the ceiling and the upper walls inside. There they behold a sight that confounds them. By the dim light inside, they see a mysterious shape in the secret room — now sharp and clear, now blurry and indistinct, now rising to the ceiling, now swooping below the level of the windows, now contracting, now expanding as if carried by huge bat-like wings. At one point the apparition turns its head to the light, and the two men clearly see the profile of a woman — a woman hovering and swooping high in the secret room on the wings of a bat!

From their perch in the tree they are able to step gingerly and noiselessly onto a narrow balcony by one of the windows, from which they have a wider view of the room. They see three men, all with a ghastly pallor to their faces, absorbed in watching the movements of the bat-woman over their heads. One of them is the man in the beaver hat. Another is unidentifiable, but the third man, as Sir James confirms in a trembling whisper, is Roger Balfour.

The bat-woman, where she hovers near the ceiling, turns her face toward the window, her eyes intent, as if to pierce the darkness beyond. Yates and Sir James take an involuntary step back into the shadows. The figure of Roger Balfour also turns to the window, his eyes keenly searching, his face ghostly pale, a small open wound crusted and discolored at his temple. Sir James shudders.

Colonel Yates whispers that they have seen enough for one night, and Sir James readily agrees. They stealthily return to the tree and cautiously climb back down to the ground. Sir James is highly agitated. In a distraught whisper he urges that they return at once to Hamlin House; God only knows what has happened to Lucy in their absence. In a sudden flash of insight, Colonel Yates realizes that Sir James’s feelings for Lucy are not merely those of a guardian for his ward.

From a rise a little distance from Balfour House they look back. In the dim light of the upper window they see a shape standing at the window, and they hear a voice, low and plaintive, calling: “Lucy — Lucy — Lucy — “

Chapter 14 – By the Light of Day

Sir James spends a sleepless night, his mind going over and over the weird events of the night and the uncanny things he and Colonel Yates have seen. The next day at noon, Lucy, alarmed at his tired and ill appearance, asks him what happened while he and the colonel were out. Feeling it best to keep her unaware, he says that they were unsuccessful in their attempt to follow the man in the beaver hat; he had eluded them, and their long walk was for nothing.

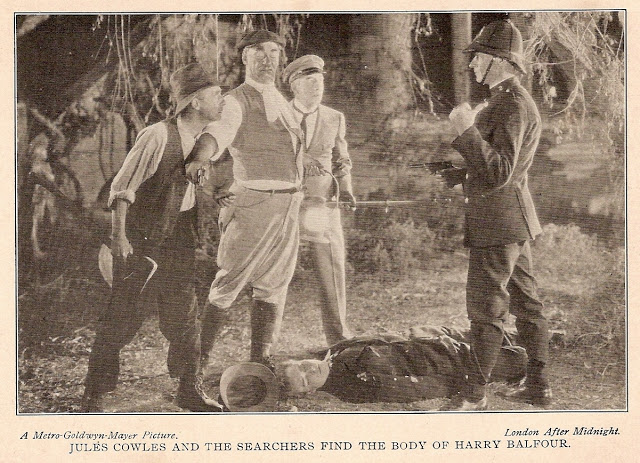

Sir James and Colonel Yates decide to return to Balfour House by daylight; they tell Hibbs that if they are not back in an hour he should send a party in search of them. Under the hot summer sun on a cloudless day, Balfour House looks impressive and looming, but empty and unthreatening. Sir James wonders, was what they saw the night before merely a figment of their imaginations? No, says Yates; they saw what they saw, but what it can mean is impossible to say. Sir James is not reassured.

They knock at the door, but there is no answer. Entering cautiously, they see no signs of occupancy, no disturbance in the dust on the tables, chairs and floor. The door to the secret room is still locked and bolted, the lock rusted and untouched. As they creep from room to room, searching, Sir James again has the unsettling feeling he had on the night they visited the Balfour crypt, that some unseen presence is following them, watchful.

As they enter the library, the room in which Roger Balfour died five years ago, a strange sight greets them: High in a corner of the ceiling are a group of five bats, hanging in silent slumber.

Chapter 15 – Two Suitors

Back at Hamlin House, Lucy waits for Colonel Yates in the rose garden; she has promised to give him a tour of the garden and a description of the blooms cultivated there. Hibbs scolds her for being alone, even in the daytime. She laughs, saying she wishes she had seen the man in the beaver hat herself; she’d have captured him! Hibbs, realizing she has been kept in the dark as to the extent of her danger, restrains himself from telling more than he should.

Sir James and Colonel Yates come into the garden. As they discuss what to do about the previous night’s events, Yates notices the flash of suspicion on Sir James’s face at the apparent intimacy between Hibbs and Lucy. Yates urges Sir James to ask Scotland Yard to investigate Balfour House; involving the local police, he says, could lead to unwanted and harmful gossip, but the Yard is renowned for its discretion. Have Hibbs write Scotland Yard, he says, asking them to send several good, able-bodied men — “men who are not afraid of man, ghost or devil” — under cover of darkness.

Sir James and Hibbs go into the house to draft the letter, leaving Yates and Lucy to their tour of the garden. As they chat, Lucy confides something she has never told anyone, not even her brother Harry: When she was a little girl, she was strangely afraid of Sir James, although she never knew exactly why; he was always so good to her. And since her father’s death, he has been kindness itself; she feels she could never repay him for all he has done for her and Harry.

Colonel Yates assures her that he understands. He tells her that he wants to have “a serious talk” with her, on a matter that concerns her closely.

From the house, Hibbs watches Lucy and the colonel in the garden. He sees Lucy throw her arms around Colonel Yates and kiss his cheek, then begin weeping on his shoulder. His jealousy flares, and it is with difficulty that Sir James recalls him to the task of writing Scotland Yard.

Later, Hibbs confronts Lucy and demands an explanation. She cannot say anything, she says, and begs him not to ask. But she mollifies him by assuring him that she intends to break the news to Sir James of her and Hibbs’s feelings for one another.

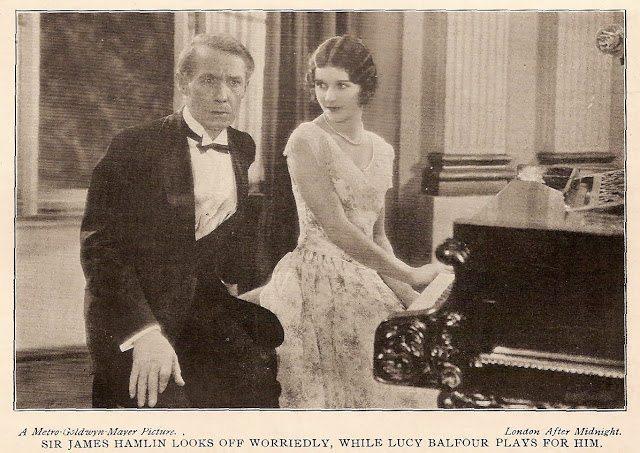

Lucy finds Sir James in the music room, as eager to speak with her as she is with him. Sir James wonders: Has Lucy been annoyed by the unwanted attentions of his secretary? No, not at all, she assures him. Before she can go on, he tells her he is glad to hear it. Hibbs could never support Lucy in a way to which she is entitled. On the other hand, he — Sir James himself — has long looked forward to making Lucy his wife.

Surprised and alarmed, Lucy runs sobbing from the room.

Chapter 16 – Exorcisms

Sir James and Colonel Yates find a passage in Yates’s book: “A wreath of tube roses at the window, a sword across the door, will make it impossible for the Vampyr to enter a sleeping room at night.” It may sound absurd, but after the past two nights nothing should be discounted; at least it can do no harm.

Hibbs is tense and upset as they place a wreath of tube roses from the garden and a sword that had hung on the wall, according to the directions in the book; lack of sleep, concern for Lucy, and mistrust of Yates are taking their toll. Reading from the book, he speaks the prescribed incantation: “They shall not pass this threshold.”

As everyone retires for the night, Yates draws Hibbs into the upstairs study, saying he has something to tell him. Ignoring the smoldering anger in Hibbs’s eyes, Yates guides him to a chair and gently forces him to sit. He tells him that Lucy’s love for Hibbs speaks well of him, that Yates can see through her eyes what a fine fellow Hibbs is.

All thought of Yates as a rival is suddenly gone from Hibbs’s mind. In the colonel’s steady gaze he sees the eyes of a friend and feels an urge to confide in him. Too bad about Lucy’s brother, Yates says; did he and Hibbs get along? Ruefully, Hibbs says no, Harry objected to Hibbs’s love for Lucy and was resolved to separate them for good.

As they talk, Hibbs is overcome with drowsiness. He sleeps.

Chapter 17 – An Assassin Foiled

Midnight. The house is still. A crouching, shadowy figure moves stealthily to the door of one of the sleeping rooms. Slowly, silently, the figure turns the knob, opens the door and slips inside. The figure approaches the sleeper in the bed, in its hand a long thin object, gleaming in the dim moonlight from the window.

As the figure is poised to strike, the sleeper lunges bolt upright, startling the attacker to flight — out the door, down the hall, with the intended victim — none other than Colonel Yates — in pursuit. Yates fires his revolver at the fleeing figure, rousing the house. Lucy calls from inside her room, asking that someone remove the sword and let her out.

Sir James comes from his room, his hands shaking as he ties the belt of his robe. What was that? Nothing, says Yates; I must have had a nightmare. Sir James and Lucy are reassured, and the house settles down.

Alone again in the hall, Yates reflects that Hibbs did not appear after the gunshot. He kneels and searches the carpet. Finally he finds what he seeks: a spot of blood. His assailant did not escape untouched after all.

Yates makes sure that Lucy’s room is still secured with the sword and tube roses, then goes to Hibbs’s room. The door is open, the bedclothes rumpled, but the room is empty. Yates deftly makes up the bed, then goes into the study, where he finds Hibbs, still sound asleep in the chair where he dozed off while they talked.

Chapter 18 – The Fallen Sword

Upon being awakened, Hibbs apologizes for his rudeness in dropping off. Don’t mention it, says Yates; on the contrary, I apologize for keeping you up so late. Yates leaves Hibbs in the study, telling him they both should be in bed.

Hibbs looks at his watch. Two-thirty! Have they really been talking so long? He hardly remembers a word they said. Before retiring, he decides to check on Lucy’s room. He is horrified to find the protecting sword missing. He pounds on the door, calling her name.

Sir James appears, alarmed at Hibbs’s display — and outraged that he addresses Lucy by her first name. Colonel Yates joins them and they break in the door to Lucy’s room. It’s empty. She’s gone.

Finally the strain of the past few days has its way, and something in Hibbs snaps. He becomes hysterical, babbling that “vampyrs” have taken Lucy, that they must all be destroyed. Colonel Yates tries to calm him, to no avail. As Hibbs runs off, delirious, there comes from the direction of Balfour House the wild, piercing scream of a woman in distress. Could that have been Lucy?

No, says Gallagher, Sir James’s Irish chauffeur. That wasn’t Miss Lucy; ’twas the wail of “the banshee o’ Balfour House,” foretelling tragedy to come.

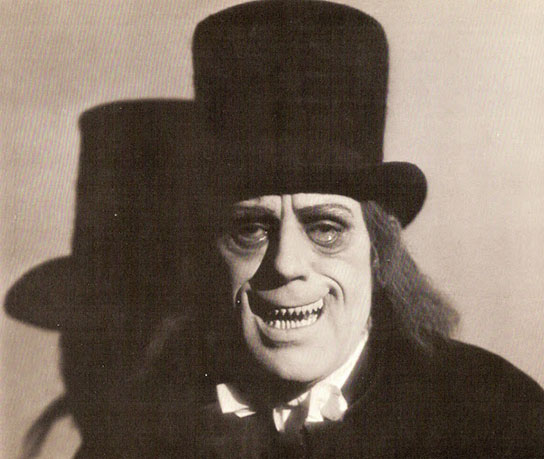

London After Midnight (MGM; 1927) is the Holy Grail of Lost Films. Oh sure, there’s the complete Greed. But we do have the incomplete Greed, and it’s a masterpiece as it stands. Besides, tell the truth: Isn’t there just the tiniest little fear, deep down in your heart, that if Stroheim’s 42-reel, ten-hour cut should miraculously turn up, it just might turn out to be a letdown, maybe even (Heresy! Heresy!) a bit of a bore? But be that as it may, we do have Greed; all we have of London After Midnight is an assortment of stills like this one of Lon Chaney in makeup and costume as the Man in the Beaver Hat.

London After Midnight (MGM; 1927) is the Holy Grail of Lost Films. Oh sure, there’s the complete Greed. But we do have the incomplete Greed, and it’s a masterpiece as it stands. Besides, tell the truth: Isn’t there just the tiniest little fear, deep down in your heart, that if Stroheim’s 42-reel, ten-hour cut should miraculously turn up, it just might turn out to be a letdown, maybe even (Heresy! Heresy!) a bit of a bore? But be that as it may, we do have Greed; all we have of London After Midnight is an assortment of stills like this one of Lon Chaney in makeup and costume as the Man in the Beaver Hat.

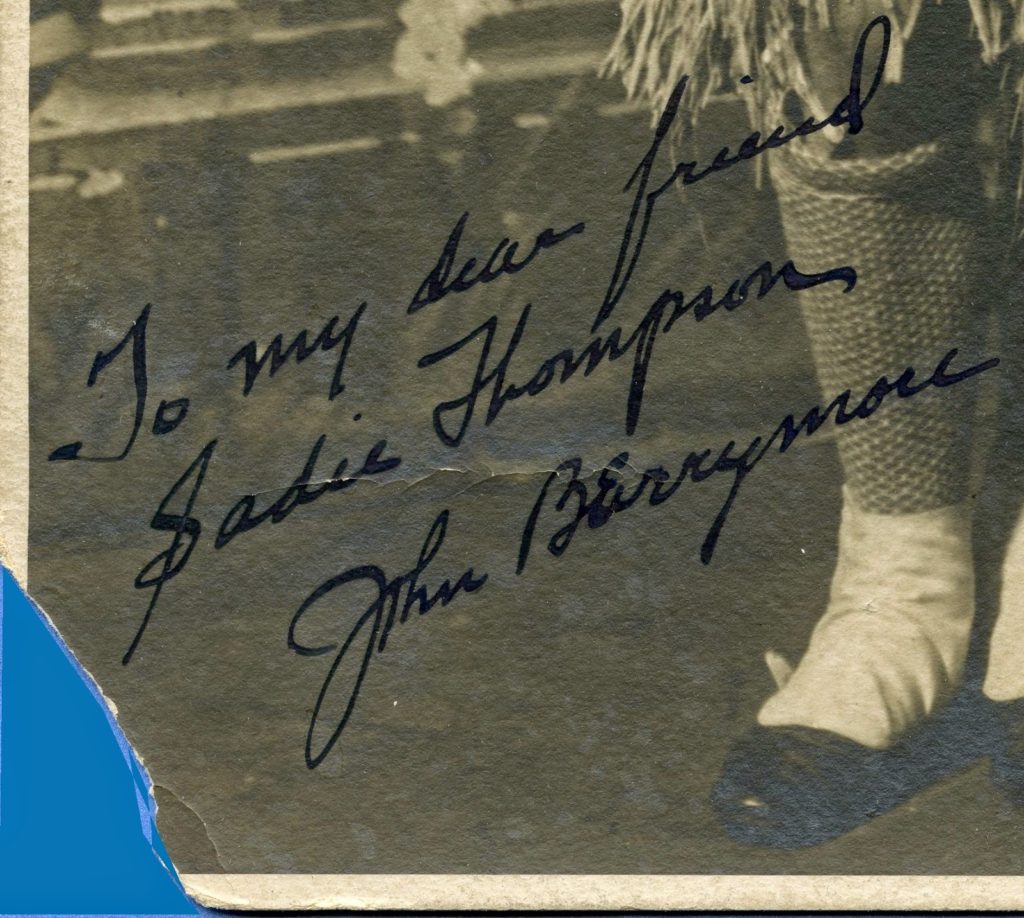

Today I received this picture from historian Richard M. Roberts, who states conclusively — and I’m convinced — that my picture isn’t John Barrymore after all. Richard’s message:

Today I received this picture from historian Richard M. Roberts, who states conclusively — and I’m convinced — that my picture isn’t John Barrymore after all. Richard’s message:

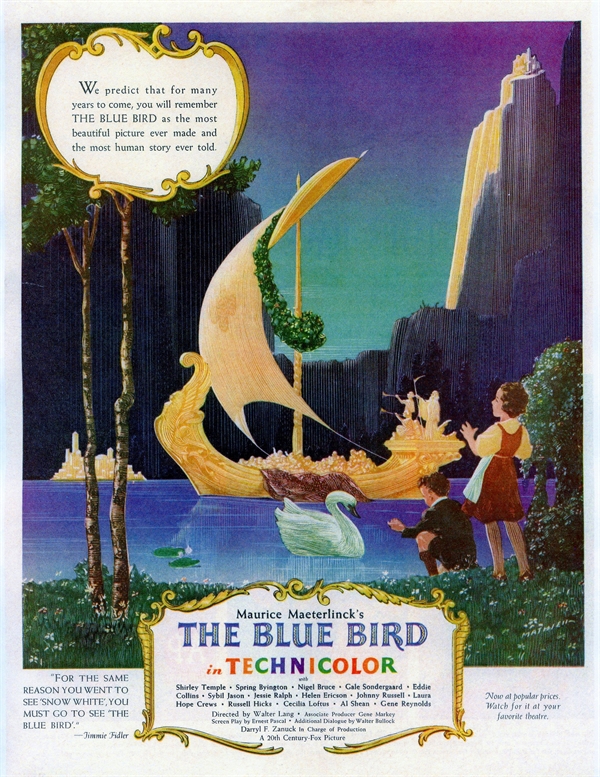

The Blue Bird was Shirley’s second brush with a Nobel Prize winner, after Rudyard Kipling and Wee Willie Winkie. Belgian poet, essayist and playwright Maurice Maeterlinck (1862-1949) was a leading proponent of the Symbolist movement in European art and literature of the late 19th century. His most influential and commercially successful play was probably Pelleas and Melisande (1893), a doomed-lovers tragedy that inspired numerous operas, all of which are performed these days far more often than the original play.

The Blue Bird was Shirley’s second brush with a Nobel Prize winner, after Rudyard Kipling and Wee Willie Winkie. Belgian poet, essayist and playwright Maurice Maeterlinck (1862-1949) was a leading proponent of the Symbolist movement in European art and literature of the late 19th century. His most influential and commercially successful play was probably Pelleas and Melisande (1893), a doomed-lovers tragedy that inspired numerous operas, all of which are performed these days far more often than the original play. Or trying to. The Blue Bird‘s greatest faults are inherent in Maeterlinck’s play; this was one case where Fox might have been justified in jettisoning everything but the title. Instead, Ernest Pascal’s script made an honest effort (with moderate success) to streamline, simplify and motivate the wild excesses of Maeterlinck’s fantasy. First, merely as a practical matter, the birth order of the lead siblings was reversed, making Mytyl (Shirley) the older and Tyltyl (Johnny Russell) the younger. The size of their expedition was streamlined, with their only companions being the cat Tylette (Gale Sondergaard, right) and dog Tylo (Eddie Collins, next to her). Of Maeterlinck’s five spirits, only Light remained (played by Helen Ericson), and she served, logically enough, as the children’s guide on their quest. (The group is shown here as they set out, with Jessie Ralph as Berylune on the left.)

Or trying to. The Blue Bird‘s greatest faults are inherent in Maeterlinck’s play; this was one case where Fox might have been justified in jettisoning everything but the title. Instead, Ernest Pascal’s script made an honest effort (with moderate success) to streamline, simplify and motivate the wild excesses of Maeterlinck’s fantasy. First, merely as a practical matter, the birth order of the lead siblings was reversed, making Mytyl (Shirley) the older and Tyltyl (Johnny Russell) the younger. The size of their expedition was streamlined, with their only companions being the cat Tylette (Gale Sondergaard, right) and dog Tylo (Eddie Collins, next to her). Of Maeterlinck’s five spirits, only Light remained (played by Helen Ericson), and she served, logically enough, as the children’s guide on their quest. (The group is shown here as they set out, with Jessie Ralph as Berylune on the left.) There follows another departure from Maeterlinck. After they escape from The Luxurys, the children must pass through a great forest. Tylette, hoping to rid herself of the children and thus gain her freedom, runs ahead of them and incites the trees (represented by Edwin Maxwell, Sterling Holloway and others) to avenge themselves on the children of the woodcutter who is always chopping them down. The trees take the bait, even calling on their old enemies lightning and fire — so eager are they to destroy the children that they willingly immolate themselves in a great forest fire. Tylette, however, has outsmarted herself; trying to lure the children to their doom, she is herself burned to death, and only the courageous efforts of the loyal Tylo enables the children to escape to safety.

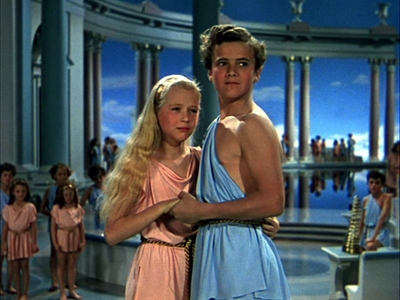

There follows another departure from Maeterlinck. After they escape from The Luxurys, the children must pass through a great forest. Tylette, hoping to rid herself of the children and thus gain her freedom, runs ahead of them and incites the trees (represented by Edwin Maxwell, Sterling Holloway and others) to avenge themselves on the children of the woodcutter who is always chopping them down. The trees take the bait, even calling on their old enemies lightning and fire — so eager are they to destroy the children that they willingly immolate themselves in a great forest fire. Tylette, however, has outsmarted herself; trying to lure the children to their doom, she is herself burned to death, and only the courageous efforts of the loyal Tylo enables the children to escape to safety.  …the Kingdom of the Future, where (returning to Maeterlinck’s text) Mytyl and Tyltyl find countless children are waiting to be born. In this remarkable scene, which looks like something designed by Maxfield Parrish, Mytyl and Tyltyl wander among the eager throng, so amazed at what they see that they completely forget to look for the Blue Bird. They meet a little girl who joyfully greets them by name (Ann Todd, not to be confused with the British actress of the same name), telling them that she will be their little sister, “in a year perhaps.” Then she adds sadly, “I’ll only be with you a little while.” Mytyl and Tyltyl wander among children who are preparing for what will be their calling in life. One boy proudly displays the anesthetic he will discover; another tinkers with an electric light. Still another, solitary and melancholy, tells them his destiny is to fight against slavery, injustice and inequality — but people “won’t listen…they’ll destroy me.”

…the Kingdom of the Future, where (returning to Maeterlinck’s text) Mytyl and Tyltyl find countless children are waiting to be born. In this remarkable scene, which looks like something designed by Maxfield Parrish, Mytyl and Tyltyl wander among the eager throng, so amazed at what they see that they completely forget to look for the Blue Bird. They meet a little girl who joyfully greets them by name (Ann Todd, not to be confused with the British actress of the same name), telling them that she will be their little sister, “in a year perhaps.” Then she adds sadly, “I’ll only be with you a little while.” Mytyl and Tyltyl wander among children who are preparing for what will be their calling in life. One boy proudly displays the anesthetic he will discover; another tinkers with an electric light. Still another, solitary and melancholy, tells them his destiny is to fight against slavery, injustice and inequality — but people “won’t listen…they’ll destroy me.”

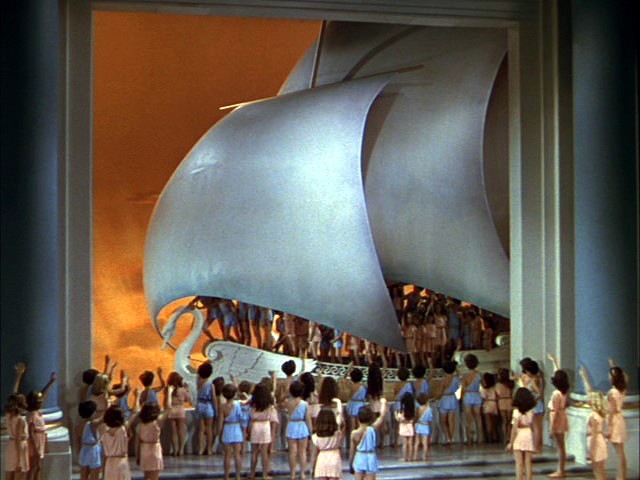

The children whose time has come board a graceful alabaster ship with silver sails and the figurehead of a swan. As the boat pulls away from the quay into a golden sea and sky, the children left behind, still awaiting their turn, bid their friends a joyous bon voyage. The departing passengers fix their eyes on the far horizon, and they sing:

The children whose time has come board a graceful alabaster ship with silver sails and the figurehead of a swan. As the boat pulls away from the quay into a golden sea and sky, the children left behind, still awaiting their turn, bid their friends a joyous bon voyage. The departing passengers fix their eyes on the far horizon, and they sing:

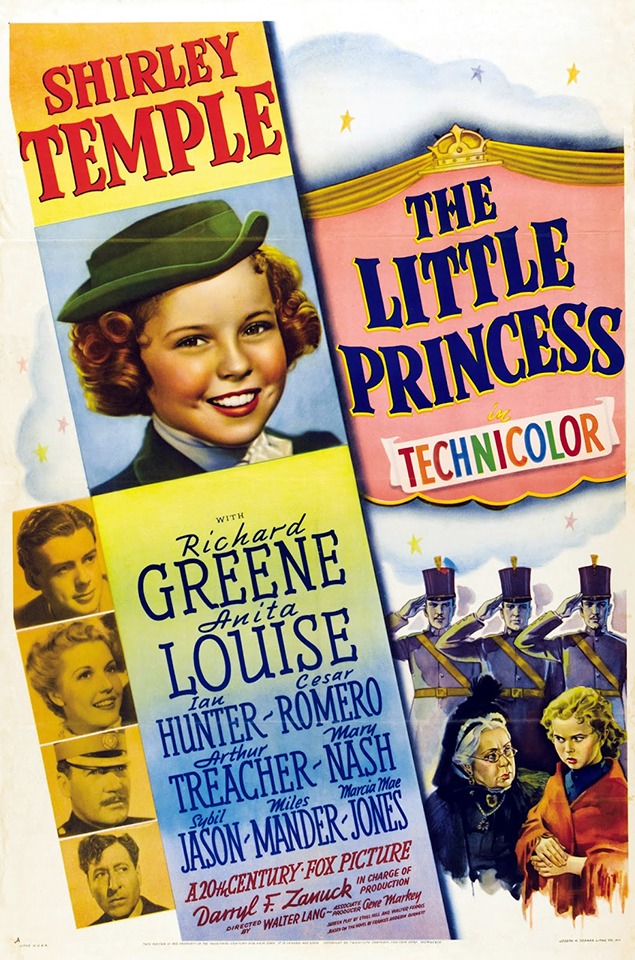

Unlike Lady Jane, A Little Princess has never been out of print since it was first published in 1905. It was the work of Frances Hodgson Burnett, who was born in England in 1849 but lived much of her adult life in the U.S., where she became a citizen in 1905, and where she died and was buried in 1924. She began writing short fiction for magazines while still in her teens, later progressing to romantic novels for adults and sentimental books for children. Her books sold well all her life, enabling her to support a transatlantic lifestyle with homes at various times in America, in England and on the Continent. Her adult novels were all popular in their day, but it’s for her children’s books that she remains best remembered, specifically Little Lord Fauntleroy (1885), The Secret Garden (1911) and A Little Princess.

Unlike Lady Jane, A Little Princess has never been out of print since it was first published in 1905. It was the work of Frances Hodgson Burnett, who was born in England in 1849 but lived much of her adult life in the U.S., where she became a citizen in 1905, and where she died and was buried in 1924. She began writing short fiction for magazines while still in her teens, later progressing to romantic novels for adults and sentimental books for children. Her books sold well all her life, enabling her to support a transatlantic lifestyle with homes at various times in America, in England and on the Continent. Her adult novels were all popular in their day, but it’s for her children’s books that she remains best remembered, specifically Little Lord Fauntleroy (1885), The Secret Garden (1911) and A Little Princess.

Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm was another of Shirley’s “no trace” pictures, like

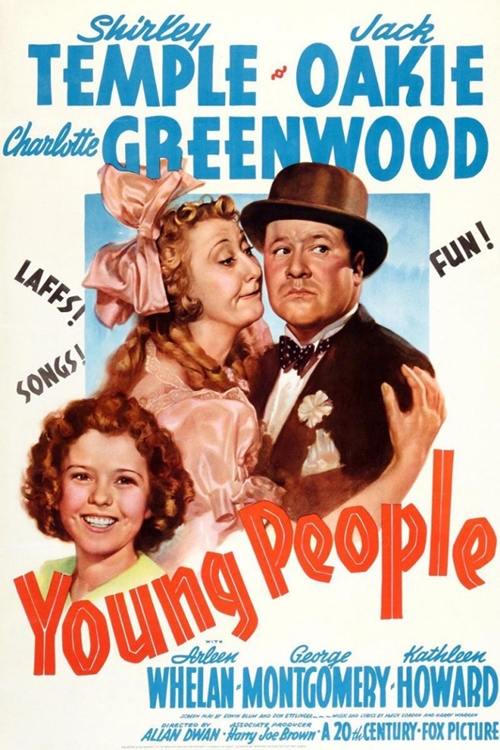

Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm was another of Shirley’s “no trace” pictures, like  Little Miss Broadway was the one Shirley called “unfailingly bland”, and that about sums it up. Shirley is once again an orphan, this time moving from her orphanage to live with a friend of her late parents (Edward Ellis) who runs a hotel for entertainers. The curmudgeon this time is the rich old landlady next door (Edna May Oliver, her middle name misspelled as “Mae”), who not only plots to get rid of those unsavory show people by selling their hotel out from under them, but (channeling Sara Haden’s truant officer from Captain January) moves to have Shirley returned to her orphanage. Meanwhile, her playboy nephew (George Murphy) is charmed by Shirley and smitten with Ellis’s daughter (Phyllis Brooks of Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm) and tries to thwart the old girl. It all ends in the courtroom of judge Claude Gillingwater, with Shirley and her troupers proving that they’ve got a moneymaking show on their hands and can afford to keep the hotel open.

Little Miss Broadway was the one Shirley called “unfailingly bland”, and that about sums it up. Shirley is once again an orphan, this time moving from her orphanage to live with a friend of her late parents (Edward Ellis) who runs a hotel for entertainers. The curmudgeon this time is the rich old landlady next door (Edna May Oliver, her middle name misspelled as “Mae”), who not only plots to get rid of those unsavory show people by selling their hotel out from under them, but (channeling Sara Haden’s truant officer from Captain January) moves to have Shirley returned to her orphanage. Meanwhile, her playboy nephew (George Murphy) is charmed by Shirley and smitten with Ellis’s daughter (Phyllis Brooks of Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm) and tries to thwart the old girl. It all ends in the courtroom of judge Claude Gillingwater, with Shirley and her troupers proving that they’ve got a moneymaking show on their hands and can afford to keep the hotel open. If Little Miss Broadway was an A-minus picture, Just Around the Corner was no more than a B-plus. If that. Shirley plays Penny Hale, who is taken out of private school when her widowed architect father (Charles Farrell) loses his job, and consequently the penthouse he and Penny have been living in, as well as the money to pay for her school. He’s now forced to work as the electrician in the apartment building where they formerly occupied the penthouse, and he and Penny must now make do with a tiny apartment in the basement.

If Little Miss Broadway was an A-minus picture, Just Around the Corner was no more than a B-plus. If that. Shirley plays Penny Hale, who is taken out of private school when her widowed architect father (Charles Farrell) loses his job, and consequently the penthouse he and Penny have been living in, as well as the money to pay for her school. He’s now forced to work as the electrician in the apartment building where they formerly occupied the penthouse, and he and Penny must now make do with a tiny apartment in the basement. So far we’ve taken Shirley up to the middle of 1937. She’s been Hollywood’s top box-office star for two years, and she’ll go on to be for two years more. This is probably a good time to deal with one of Hollywood’s most persistent and tantalizing legends: Is it true that Shirley Temple was originally set to play Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz? The short answer is: No, but there may be a complicated grain of truth to the legend. In fact, given Shirley’s stature in the industry during the mid-to-late 1930s, it’s unlikely that there wouldn’t be something to it.

So far we’ve taken Shirley up to the middle of 1937. She’s been Hollywood’s top box-office star for two years, and she’ll go on to be for two years more. This is probably a good time to deal with one of Hollywood’s most persistent and tantalizing legends: Is it true that Shirley Temple was originally set to play Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz? The short answer is: No, but there may be a complicated grain of truth to the legend. In fact, given Shirley’s stature in the industry during the mid-to-late 1930s, it’s unlikely that there wouldn’t be something to it. According to Variety, Heidi was chosen for Shirley by public demand, as expressed in her fan mail — although the showbiz bible may simply have been parroting a studio press release. Either way, the role was a natural for Shirley. The source was a novel by Johanna Spyri (1827-1901), first published in the author’s native Switzerland in 1880. The book was instantly popular, and promptly translated from its original German into virtually every written language on Earth. The book was — and remains — so popular, in fact, that it’s surprising to realize that Shirley’s picture in 1937 was the first attempt to make a movie out of it (there have been over a dozen since).

According to Variety, Heidi was chosen for Shirley by public demand, as expressed in her fan mail — although the showbiz bible may simply have been parroting a studio press release. Either way, the role was a natural for Shirley. The source was a novel by Johanna Spyri (1827-1901), first published in the author’s native Switzerland in 1880. The book was instantly popular, and promptly translated from its original German into virtually every written language on Earth. The book was — and remains — so popular, in fact, that it’s surprising to realize that Shirley’s picture in 1937 was the first attempt to make a movie out of it (there have been over a dozen since).

Then disaster strikes — incredibly enough, in the form of exactly the sort of thing Darryl Zanuck said he didn’t want in Wee Willie Winkie. As Heidi and her grandfather sit at their cabin table, he ostensibly begins reading her a story about “The Magic Wooden Shoes”. The camera moves in on a woodcut in the book, and the picture dissolves to a quaint little Dutch scene by a storybook Zuider Zee, and there’s Shirley — or is it Heidi? — in blonde braids and bangs and a starched cap, singing about her shoes:

Then disaster strikes — incredibly enough, in the form of exactly the sort of thing Darryl Zanuck said he didn’t want in Wee Willie Winkie. As Heidi and her grandfather sit at their cabin table, he ostensibly begins reading her a story about “The Magic Wooden Shoes”. The camera moves in on a woodcut in the book, and the picture dissolves to a quaint little Dutch scene by a storybook Zuider Zee, and there’s Shirley — or is it Heidi? — in blonde braids and bangs and a starched cap, singing about her shoes:  But looking back, we can see the handwriting on the wall. For me, seeing Heidi again for the first time in nearly 60 years was an eye-opening shock. I had remembered it as one of Shirley’s best-loved pictures. In fact, it always perplexed me that the 1952 Swiss version, which I saw about the same time, stayed fresher in my memory over the decades. Seeing Shirley’s again, I’m no longer perplexed. Heidi is no doubt one of her best-loved pictures, but it’s not one of her best. Despite those very good early scenes, and some later ones like the scene where the grandfather accompanies Heidi to the church that he hasn’t visited in years (straight out of Frau Spyri’s novel), the picture never recovers from the miscalculation of “In Our Little Wooden Shoes”; it’s one of the head-scratching what-on-Earth-were-they-thinking moments of 1930s Hollywood. What they were thinking, I suspect — or more to the point, what Darryl Zanuck was thinking — was that his dictum about writing the story as if it were a Little Women or David Copperfield, about writing for Shirley as an actress and not depending on any of her tricks, was no longer operative. Henceforth, as far as 20th Century Fox was concerned, Shirley’s tricks would be her stock in trade. The studio was no longer interested in Shirley becoming an actress; instead, they would keep her a baby taking a bow for as long as they could get away with it.

But looking back, we can see the handwriting on the wall. For me, seeing Heidi again for the first time in nearly 60 years was an eye-opening shock. I had remembered it as one of Shirley’s best-loved pictures. In fact, it always perplexed me that the 1952 Swiss version, which I saw about the same time, stayed fresher in my memory over the decades. Seeing Shirley’s again, I’m no longer perplexed. Heidi is no doubt one of her best-loved pictures, but it’s not one of her best. Despite those very good early scenes, and some later ones like the scene where the grandfather accompanies Heidi to the church that he hasn’t visited in years (straight out of Frau Spyri’s novel), the picture never recovers from the miscalculation of “In Our Little Wooden Shoes”; it’s one of the head-scratching what-on-Earth-were-they-thinking moments of 1930s Hollywood. What they were thinking, I suspect — or more to the point, what Darryl Zanuck was thinking — was that his dictum about writing the story as if it were a Little Women or David Copperfield, about writing for Shirley as an actress and not depending on any of her tricks, was no longer operative. Henceforth, as far as 20th Century Fox was concerned, Shirley’s tricks would be her stock in trade. The studio was no longer interested in Shirley becoming an actress; instead, they would keep her a baby taking a bow for as long as they could get away with it.  Calling the picture “Rudyard Kipling’s” Wee Willie Winkie was a bit of an overstatement. The original story was published in 1888, when the future Nobel Prize winner was 22. It told of Percival William Williams, the six-year-old son of an army colonel stationed with his regiment in British India at the foot of the Khyber Pass on the indistinct border with Afghanistan. Percival has a penchant for nicknaming people, including himself, so he has adopted the name Wee Willie Winkie from one of his nursery-books. Winkie is bright but typically mischievous for a boy his age, and under the military discipline imposed by his father he is forever earning, then forfeiting, a succession of Good Conduct Badges.

Calling the picture “Rudyard Kipling’s” Wee Willie Winkie was a bit of an overstatement. The original story was published in 1888, when the future Nobel Prize winner was 22. It told of Percival William Williams, the six-year-old son of an army colonel stationed with his regiment in British India at the foot of the Khyber Pass on the indistinct border with Afghanistan. Percival has a penchant for nicknaming people, including himself, so he has adopted the name Wee Willie Winkie from one of his nursery-books. Winkie is bright but typically mischievous for a boy his age, and under the military discipline imposed by his father he is forever earning, then forfeiting, a succession of Good Conduct Badges. Needless to say, in Ernest Pascal and Julien Josephson’s screenplay nearly all of this was changed. Percival was changed to Priscilla and given a widowed American mother (June Lang). The colonel backs up a generation, becoming Priscilla’s grandfather (C. Aubrey Smith), who sends for Priscilla and her mother when he learns they are living in poverty in America. Priscilla is still nicknamed Wee Willie Winkie, but her military discipline is self-imposed in an effort to become a soldier, since that seems to be the only type of person her grandfather the colonel likes. “Private” Winkie still takes a shine to Lt. “Coppy” Brandis (Michael Whalen, Shirley’s father in Poor Little Rich Girl), but he throws over Maj. Allardyce’s daughter to romance Winkie’s mother. While he’s doing that, Coppy’s duties as Winkie’s best friend among the soldiery devolve onto a new character, Sergeant MacDuff (Victor McLaglen).

Needless to say, in Ernest Pascal and Julien Josephson’s screenplay nearly all of this was changed. Percival was changed to Priscilla and given a widowed American mother (June Lang). The colonel backs up a generation, becoming Priscilla’s grandfather (C. Aubrey Smith), who sends for Priscilla and her mother when he learns they are living in poverty in America. Priscilla is still nicknamed Wee Willie Winkie, but her military discipline is self-imposed in an effort to become a soldier, since that seems to be the only type of person her grandfather the colonel likes. “Private” Winkie still takes a shine to Lt. “Coppy” Brandis (Michael Whalen, Shirley’s father in Poor Little Rich Girl), but he throws over Maj. Allardyce’s daughter to romance Winkie’s mother. While he’s doing that, Coppy’s duties as Winkie’s best friend among the soldiery devolve onto a new character, Sergeant MacDuff (Victor McLaglen).

Seen today, Wee Willie Winkie bears out Shirley’s opinion more than it does Mosher’s, Flin’s or Nugent’s. The picture is certainly not too long. Children may squirm during the protracted love scenes between Michael Whalen and June Lang, but so do adults. Both were bland Fox contract players on an unstoppable career path toward B pictures and, at the onset of middle age, television. Whalen’s dark good looks were about to be rendered irrelevant by the rise of the far more charismatic Tyrone Power. As for Lang (Shirley’s “mother” was only 11 years older than she was), within seven years she would be a nameless, uncredited “Goldwyn Girl” behind Danny Kaye in Up in Arms, and would finish her career with one-off guest shots on TV cop shows in the ’50s and ’60s. Whalen and Lang were (and remain) attractive and inoffensive, but they lack the chemistry — with either the audience or each other — that Robert Young and Alice Faye showed in Stowaway, or Faye and Jack Haley in Poor Little Rich Girl. (The blue-green of this frame-cap, like the sepia of others, reproduces the tinted stock Wee Willie Winkie sported on its original release.)

Seen today, Wee Willie Winkie bears out Shirley’s opinion more than it does Mosher’s, Flin’s or Nugent’s. The picture is certainly not too long. Children may squirm during the protracted love scenes between Michael Whalen and June Lang, but so do adults. Both were bland Fox contract players on an unstoppable career path toward B pictures and, at the onset of middle age, television. Whalen’s dark good looks were about to be rendered irrelevant by the rise of the far more charismatic Tyrone Power. As for Lang (Shirley’s “mother” was only 11 years older than she was), within seven years she would be a nameless, uncredited “Goldwyn Girl” behind Danny Kaye in Up in Arms, and would finish her career with one-off guest shots on TV cop shows in the ’50s and ’60s. Whalen and Lang were (and remain) attractive and inoffensive, but they lack the chemistry — with either the audience or each other — that Robert Young and Alice Faye showed in Stowaway, or Faye and Jack Haley in Poor Little Rich Girl. (The blue-green of this frame-cap, like the sepia of others, reproduces the tinted stock Wee Willie Winkie sported on its original release.)