THE SENSIBLE CHRISTMAS WISH

The aging steam locomotive sat chuffing and hissing in the sharp December air. Cynthia and her mother walked quickly along the platform, so quickly that Cynthia felt herself huffing almost as loud as the engine itself in her effort to keep up.

Mother had said hardly a word to Cynthia all morning. She had been moody and quiet as they packed the trunk and carpetbag for the trip. The only time she had spoken more than a few words had been at the hotel, when she arranged with Barney Hart for the wagon to take the trunk to the station. Barney had acted strange, asking Mother several times if she was sure. Cynthia never knew Barney to be so thick-headed.

Cynthia and her mother had waited in the lobby of the only hotel in Fairbanks for the wagon to take them to the depot to catch the train for Anchorage. Bored with waiting, Cynthia had gone into the general store Barney operated next door; she wanted to take another look at Rose-Marie.

Rose-Marie was the most beautiful doll Cynthia had ever seen, the most beautiful doll she could imagine. With Christmas coming, Barney Hart had ordered a few toys and gifts to mingle with the flour, sugar, salted meats, canned foods, tools and dry goods that normally stocked his store. Rose-Marie stood among them like a queen holding court in a crude frontier shack. She was nearly three feet tall, and to Cynthia she seemed almost life-size. She was made of fine French porcelain, dressed in a flowing ball gown of pink satin and white lace, and hand-painted so that her eyes and cheeks seemed to glow with a life of their own. On her head a glittering tiara rested on golden human hair that Barney said had been sewn in place one strand at a time. Rose-Marie took Cynthia’s breath away, and she wanted this doll more than she had ever wanted anything.

Cynthia had once shown Rose-Marie to Mother and Papa, and they had agreed that Rose-Marie was no ordinary doll. She had no ordinary price tag, either: whoever took Rose-Marie home would have to give Barney Hart the unheard-of sum of fifteen dollars for her. It was true, as Papa often said, that this was Nineteen-Hundred-and-Three, and that a dollar did not buy what it used to, especially up here on the edge of the Alaskan wilderness. Still, fifteen dollars seemed a fortune to Cynthia, and when she finally found courage to ask her parents for Rose-Marie for Christmas, she had not been surprised at their answer. “We’ll see,” they had said. Cynthia had pleaded, persisted, promised never to ask for anything, ever again. “Cynthia, be sensible. I said we’ll see.”

Be sensible. Those words stopped all arguments. But Cynthia’s parents didn’t use them just to keep her quiet. When they told her to be sensible they were telling her to stop, and to think. They had always raised her to be thoughtful and reasonable. Cynthia was a very sensible girl — not only in the way that means logical, but in the way that means sensitive. But oh, how she wanted that lovely French doll.

She had even dared to mention it to Mother as Barney drove them to the station. “Mother,” she had said, “do you think Papa will bring Rose-Marie with him when he comes?”

Mother had not looked at her, and had answered in a tense voice. “I doubt it, dear.”

Cynthia had pouted. “But it’s almost Christmas. And what if –.”

“Cynthia, please,” Mother had turned to her then. Her clear blue eyes were glistening and her cheeks were flushed, smarting from the early-Winter wind. Behind her eyes, Cynthia could see, Mother was sharp and watchful as an injured cat. “I don’t want to talk about dolls right now.”

Cynthia had seen something else in Mother’s eyes then, and it made her stop, even more than Mother’s words. Later, as they sat in the waiting room of the Fairbanks depot, and even now, hurrying to keep up with her mother along the train platform, something told Cynthia not to ask again if Papa would be coming with them.

It was the fifteenth of December, and Alaska was already a white wilderness. Before long the deep Winter would set in, and the train between Fairbanks and Anchorage would close down until the Spring thaw. Mother and Papa had often argued about the Winter, late at night as Cynthia lay in bed and supposedly asleep. Mother would say that her daughter should not spend another Winter in Fairbanks, getting old and worn before her time. Papa would answer that he could not spend a whole season so far from his claim. Then they would stop arguing about Winter and start arguing about gold. They had had this argument once again only last night, their voices growing to harsh whispers because they dared not shout in that small house. Papa had left then, slamming the door behind him.

Cynthia understood little of what Mother and Papa said when they talked about gold. But she understood even less when they argued about the Winter. To her, Winter was not a time when children got old and worn, but an almost magical time when Fairbanks became like a little warm island in an endless sea of ice and snow. Cynthia would often imagine great howling monsters somewhere out in the Winter night, but it was a delicious fear to her, for she always felt safe and protected. After all, she was only nine years old, and Fairbanks was the only home she had even known.

Now, as Mother led her aboard one of the passenger coaches, Cynthia felt the cold air catch in her throat, and suddenly the Wintertime seemed able to hurt her as it never had before.

The train carried five passenger coaches, each one painted a faded, smudged and weathered shade of yellow. They were small; as Cynthia and her mother walked down the aisle she counted only eight rows of seats. They were the first to board, so they got the warmest seats up front near the iron stove that heated the whole car.

Cynthia got the seat by the window, on a wooden bench covered by a thin leather pad. Overhead, from the ceiling of the car, hung three lamps, which burned almost continuously in the December darkness of Alaska, filling the car with the smell of kerosene. As Cynthia and her mother settled into their seats, Cynthia looked out the sooty, snow-streaked glass at the depot. A movement in the lighted doorway of the depot caught her eye, and she saw a tiny figure come hurrying along the platform. At first Cynthia took the figure to be a child, but as the stranger rushed past her window Cynthia saw his face clearly. It was a little man, quite the smallest person Cynthia had ever seen, even smaller than herself. He wore rubber boots and a thick wool coat that made him seem even smaller and rounder than he was. On his head he wore a red wool cap, and his face was as happy and as friendly as a Christmas nutcracker. He seemed to be heading for the train, but if he boarded, it must have been several cars down, as he was quickly out of sight.

That’s funny, Cynthia thought, I’ve never seen him before. And she knew nearly everybody in Fairbanks, at least by sight. Strangers were few so far north.

Before long the train began to lurch into life, and Cynthia watched the frail wooden buildings of her home town gradually disappear. Soon they were deep in the Alaskan forest — pine, spruce and alder, red and yellow cedar, hemlock and tamarack trees that grew anyplace where people had not cut them down to make way for tiny villages and towns.

Mother sat still in her seat, absent-mindedly patting the combs that held her strawberry-blonde hair in place. She glanced around her but seemed to take no interest in the train, the other passengers, or the passing countryside. Cynthia looked at her. Perhaps all mothers seem tall and slender, but Cynthia’s really was — almost as tall as Papa. She had long, delicate hands, a graceful profile, and eyes like two clear mountain lakes. Mother was always calm and self-possessed, but there were times when her eyes seemed deeper and darker than usual. This was such a time, and Cynthia knew that Mother was very troubled. She wanted to talk to her, but wondered if she should. I’ll wait, she thought. I’ll count the trees out the window, and when I’ve counted two hundred maybe she’ll be ready to talk.

It didn’t take Cynthia long in the Alaskan wilderness to count two hundred trees. “Mother,” she said, “what are we going to do after we get to Anchorage? Are we going to Seattle?”

“Yes,” Mother said, and for the first time she smiled at Cynthia. “I thought we might spend Christmas with Grandmother and Grandfather. You’ve gotten to be such a big girl, and they haven’t seen you in so many years. It will be good to see them again, don’t you think?”

Cynthia nodded, and her sensible side told her again not to ask about Papa. Or about Rose-Marie, even though Mother had mentioned Christmas herself. She wondered if there were dolls like Rose-Marie in Seattle. What was Seattle like, anyway? She had been born there, but she had no memory of it. In fact, although she had very early memories — dim memories, about to vanish, of a time when she could not even walk or speak to her parents — she could not recall ever having lived anywhere but Fairbanks. She had always lived in the same house and gone to the same one-room school with the same twenty-three children. Perhaps a baby here, a “graduation” there, but Cynthia could scarcely imagine a town with more than one school, or so many children that she might never know them all.

“How long is the ride to Anchorage, Mother?” she asked.

“Oh, it’ll take all day, dear. We won’t be there till this evening.”

“Does this train go all the way to Seattle?”

“Not this one. But we’ll be taking the boat from Anchorage anyway. That takes about a week.”

A week! It was early in the morning of the first day, and Cynthia was already farther from home than she had ever been before! How far could she go in a week?

Of course, it only made sense. She had seen it all in the atlas in school. Still, those had only been maps. Now, to Cynthia, the neat pink and brown and blue illustrations had been transformed into mountains and forests and seas and valleys and farms and towns and cities.

Cynthia looked again out the window, and in that weird half-light that is a December day in Alaska, it seemed to her that those great, howling monsters she sometimes imagined were even closer and more real. She began to see the snowfall not as a great white blanket but as a gleaming, icy flood drowning all in its path. In this fancy, it seemed to Cynthia that the trees of the forest were like great beasts trapped in the flood, surging to break free yet frozen at the moment of death. For the first time, Cynthia saw that Winter can be a lonely and dangerous time, and the thought made her sad. Be sensible, she told herself. You can’t let Mother see you cry over a bunch of trees.

By now the train was climbing steadily uphill, winding through the mountain passes that would soon be closed until April. The train would slow with the climb, then regain speed as it crested a hill or a curve on the long way up. On one of these slight downward curves, the train slowed and slowed until it came to a stop. Looking out the window, Cynthia could see a rickety wooden shelter with a red lantern hung on a staff beside it. Someone had flagged down the train and was already buying a ticket for the passage from the conductor. Cynthia could not see them, but she could hear their muffled voices through the door at the front of the car. Then she saw the conductor step down to the shelter, blow out the red lantern, and signal to the engineer as he climbed back aboard.

As the train started up again, the new passenger came through the door at the front of the car. He was dressed in an enormous wool overcoat with a red plaid pattern, a fur cap with earmuffs and a long white scarf that covered the whole lower half of his face. He carried a small canvas pack in one hand and a pair of snowshoes slung over his shoulder. He stepped around the iron stove and dropped his pack in the empty seat opposite Cynthia and her mother.

He unwound the white scarf from his face, revealing an even whiter beard underneath. As he pulled the scarf away the beard fell down past the top button on his coat. He smiled and bowed slightly to Cynthia and her mother. “Do you ladies mind if I join you?” he asked.

“Not at all,” Mother said, and the stranger sat down opposite them, scooting his pack to the seat beside him and tucking his snowshoes underneath. He unbuttoned his overcoat and removed his fur cap. Under the cap his head was white-haired and almost bald, and his open coat showed suspenders and a thick flannel shirt over a broad, expansive belly. Cynthia looked him over from his boots to his snow-white hair, and was surprised to see him smiling at her, his eyes crinkling behind cheeks still red from the cold. “Right chilly out there,” he said through his smile, “good weather to be in out of.”

“I’ll bet,” said Cynthia, unable to think of anything better. The old stranger began digging in his canvas pack, finally pulling out a yellowing clay pipe and a tobacco pouch. He showed them to Cynthia’s mother. “Mind if I smoke, ma’am?” he asked.

“I don’t mind,” Mother said politely, smiling (it almost seemed) in spite of herself. Cynthia said nothing, though in fact she welcomed the thought of the old man’s pipe, hoping it would make her think of her father, who also smoked a pipe after supper at home. As the old man filled and lit his pipe Cynthia wondered if she would ever again see Papa going through the same motions.

Before long the old man had a thin halo of smoke hovering over his head in the heavy air of the railroad coach. The scent from his pipe reminded Cynthia of a campfire deep in the forest on a cold Winter night, and made her feel strangely warm and cozy inside.

All the while he was filling and lighting and puffing on his pipe, the old man never lost his friendly smile. Finally he spoke. “I don’t mind telling you,” he said, “it’s surely a relief to be aboard this train at last. I wasn’t looking forward to waiting much longer at that drafty old shelter.”

“What were you doing there?” Cynthia asked.

“Cynthia,” Mother warned, “that’s none of your business.”

“I don’t mind, ma’am,” the old man said. “Truth is, I was on my way into Fairbanks to catch this train. But I guess I got too late a start. Just can’t seem to drag these old bones out of bed anymore of a morning. Knew I’d never make it to town in time, so I decided to head for that station instead.”

“Do you live around here?” Cynthia asked, thinking that this funny old man was the second total stranger she had seen today.

“Afraid not, miss. My home is away up past Point Barrow. Just passing through these parts on business, you might say.”

Cynthia could hardly make sense of that. “What in the world kind of business brings you into these mountains at this time of year?” she asked.

“Cynthia,” Mother’s voice was sharp, “the gentleman hasn’t done anything to deserve so many nosy questions.”

The old man chuckled around the pipe clenched in his teeth. His laughter had a warm, bubbling sound, as friendly as his smile and his snowy beard. “Curiosity’s a good trait, ma’am. Sign of a healthy mind. If you’ll excuse me, though, I think I’ll have a look around the train. I was supposed to meet a friend of mine at the Fairbanks station, and I should make sure he caught the train without me.” Then he was up and away down the aisle of the car, leaving his gear on the seat and trailing silvery wisps of pine-scented smoke.

“What a funny old man,” Cynthia said after he was gone. “I wonder who he is.”

“Nobody in particular, dear, I’m sure,” Mother said. “My, aren’t you full of questions today.” And Cynthia saw a sad loneliness in her mother’s eyes, reminding her of other questions she knew she should keep to herself. She looked out the window again and tried not to think of Rose-Marie, or of Papa.

Who was that old man, anyway, and why did he say he lived “up past Point Barrow”? Point Barrow was over five hundred miles north of Fairbanks, and if Cynthia had little understanding of that distance, at least she knew from her schoolbooks that there was nothing — nothing — past Point Barrow, only ice and snow and freezing bitter cold.

There was nothing cold or bitter about this white-bearded stranger. He was so warm, so friendly…so jolly — that was the word Cynthia really had in mind. Don’t be silly, she told herself. This white-haired old man had her thinking things that were anything but sensible.

Cynthia leaned her head back against the seat. The car swayed gently as the train climbed farther into the mountains, and Cynthia could still smell the last traces of smoke from the old man’s pipe.

* * *

The smell of the campfire somehow reached Cynthia before the sight of it did. The fire had been built with dry pine cones as kindling, and the smell of them dulled the edge of the frozen air.

Now she could see the flames, dancing orange and gold, casting black shadows on the blue-white snow. The snow rolled in hillocks around the fire, glistening like crystal, like jewels — like nothing Cynthia had ever known. A snowflake passed close to her eyes, and she actually saw its lacy pattern roll past like the wheel of a wagon. Then it was gone on a gust of wind, whirling away to nothing.

“What was that sound?” Cynthia said. But she hadn’t heard anything.

“Yes, you did,” said a crackly little voice. Sitting across the fire from Cynthia was the little man from the Fairbanks station, his nutcracker face grinning at her. Cynthia had a feeling he had always been there. “That’s the train. You’re on it, really.”

No, I’m here, she thought. Is this a dream or something?

“Does it feel like one?” the little man asked.

“Was I talking?”

“Oh,” he said, as if to say, that makes sense.

Beside Cynthia sat Rose-Marie, bundled in white fur, her eyes glittering in the firelight. She’s alive, Cynthia thought, although the doll didn’t move or seem to be breathing.

The little man got up and began walking around picking up sticks and twigs. When he had an armload he tossed them on the fire, and the flames danced higher, causing Rose-Marie’s eyes to gleam and sparkle.

“She blinked,” Cynthia said, and her voice echoed on the magical midnight snow. “She’s alive.”

The little man snorted. “Looks like a doll to me.”

Cynthia looked again. Somehow she and the little man were standing beside a towering pine tree some distance from the fire. Over their heads the tree’s green-black branches spread like wings in the darkness.

Rose-Marie sat leaning against the knotty trunk staring at Cynthia. Her cheeks seemed puffy and red, her big, bright eyes had become sharp and beady. And she was bigger than before, bigger than the little man and almost as large as Cynthia herself.

“She’s growing.”

The little man stopped and glared at Cynthia over his armload of sticks. “It’s a doll,” he said, as if that were that.

They were far from the fire now. How did we get here? Cynthia thought. She felt a little lonely, a little scared, and somehow tired, as if she had been carrying something very heavy.

She looked around for the fire, shivering from the cold. Finally she saw the fire flickering away at a great distance, a tiny orange flame hardly bigger than a star in the blue-black sky. How did we come so far? Cynthia thought.

“Keep your doll, if that’s what you want,” said the little man. He was back warming himself by the fire. Cynthia couldn’t see him — the fire was too far away — but somehow she knew he was there.

It’s cold, Cynthia thought, wrapping her arms around her and rubbing her shoulders. The trees seemed closer together and blacker than pitch.

The wind began to whistle, and a sound arose that Cynthia could not place. It sounded like a wail, a cry, a roar. The cold, the wind and the sound made the hair on her neck tingle, and she gasped a deep, chilling breath.

I’m lost, she thought, feeling her panic begin to grow. She could no longer see the fire at all, anywhere. Overhead the darkness and the twisted trees loomed over her.

“Storm coming,” said the little man’s voice. “Better come back where it’s safe.” The voice was calm and seemed nearby, but he was nowhere to be seen.

“Where are you?” Cynthia called, and her voice, unlike the little man’s, echoed in the forest. The snow around her glowed and sparkled with a life of its own. When she called out again she could hear her own fear, and it grew, like the monstrous trees. “Where are you? I can’t find you!”

“Where are you?” came the voice of the little man as Cynthia ran among the trees, searching. “I haven’t gone anywhere.”

In her hurry to find the campfire, Cynthia almost stumbled over Rose-Marie. The doll was larger, it was clear now. She was bloated and ugly, with tiny piggy pinpoint eyes.

The sound, the cry that Cynthia heard grew louder, nearer. The wind lashed her face until the tears came. The wind rattled the branches of the dense trees and they groped like claws, snatching at Cynthia’s billowing hair.

A gust of wind caught Rose-Marie, and she sailed into the air like a balloon. The look on her fat, shining face did not change as she grew tangled in the branches of the trees. She tumbled from branch to branch, from tree to tree, like a bundle changing hands. Finally the galloping wind shook her loose and she came sailing down upon Cynthia.

Cynthia screamed, her voice swallowed in the wind, and threw up her hands to defend her. Rose-Marie landed squarely in her arms and bore her down into the drifted snow. Cynthia struggled and kicked against the weight of the huge doll, but was unable to get free. She felt the wet chill of the snow on her back, sinking into her bones, freezing her heart.

The monster trees bent over her and reached down to press Rose-Marie and Cynthia deeper into the cold, killing snow. The cry of the monsters pierced her ears, and through it she heard the little man’s calm, mocking voice. “Can’t help you now,” he said, “you’re on your own.”

The shriek was everywhere now, and Cynthia fought for breath. This is no dream, she wanted to shout, this is really happening!

* * *

Cynthia awoke with a start, hearing the last of the piercing train whistle. The frantic pounding of her heart slowed as she looked around her and recognized the wood stove, the kerosene lamps, the leather-covered seats of the railroad coach.

Her gasping breath returned to normal, more quickly than she would have thought. She stretched and yawned, blinking around her as she came awake. The train no longer seemed to be climbing up into the mountains, so Cynthia guessed that they must be at least halfway to Anchorage. Mother was asleep, half-sitting, half-lying on the seat opposite, cradling her head on the old man’s pack as if it were a pillow.

The fear from the dream had all but left Cynthia now, but she still felt watchful and uneasy, as if the tree-creatures lurked just beyond the train’s frosted windows waiting to seize her again. She wondered what had become of the old man, and looked around her. She spotted him sitting by himself at the rear of the car, still smoking his clay pipe. He held the stub of a pencil in his fist and was jotting some notes or figures to himself in a little cloth-bound notebook.

Cynthia got up from her seat and headed down the aisle of the car, past the other scattered passengers as they sat dozing or staring out the windows or trying to read by the flickering ceiling lamps. One or two watched with mild interest as Cynthia passed. She walked down to the old man and stood watching him until he looked up from his notebook and smiled at her.

“My mother’s asleep,” Cynthia said.

The old man glanced up at the sleeping woman. “I’m not surprised. The poor lady looked like she could use some rest.”

“Is that why you didn’t come back and sit with us?”

“You were both asleep when I came back. Thought I’d best not disturb you.” He gestured with his pencil at the seat opposite him. “Now you’re up, you’re welcome to join me if you care to.”

Cynthia sat down. “Did you find your friend?”

The old man’s pipe had gone out, so he took it from between his teeth and tucked it into his coat pocket. He nodded. “I did. He’s a couple cars back.”

“Are you going to Anchorage together?”

He nodded again. “We have the same business there. He’s sort of an agent of mine.”

“Like a railroad agent.”

There was that warm chuckle again. “A little…only different.”

“What are you writing about?”

“Oh, just a few notes on the weather; snowfall, wind, things like that.”

“Is that your job? Studying the weather?”

He laughed. “Not exactly. But a body can’t do anything in this part of the world and not take account of the weather.”

The old man closed his notebook and slipped it into his shirt pocket. He folded his hands in his lap. “But enough about me. How about you? What are you going to do in Anchorage?”

“Mother and I are on our way to Seattle. We’re going to spend Christmas with my grandparents.”

“Umm. You’ll like Seattle. It’s a good place to spend Christmas.”

“You’ve been there? Do you know my grandparents?”

He shook his head. “Just visited the place. Don’t really know anyone there.”

They rode a while in silence. Cynthia could hear the muffled whistle of the wind in the trees passing her window. She couldn’t see the monsters, but she knew they were out there.

“Papa’s not going with us,” she said suddenly, surprising herself, as if the old man had asked her about it.

“Oh. I see.” For a long time the two of them were quiet again.

As she watched the trees and hills roll past, Cynthia could almost feel again the cold soaking snow she had dreamed about. Would I drown or freeze? she wondered. Finally she said, “What’s it really like, the Winter? I mean, I’ve never been out in it for more than a few minutes. I’ve hardly even been out of sight of my house. Is it as cruel and terrible as it seems?”

The old man nodded. “In these parts the Wintertime forgives few mistakes, that’s certain.”

“Oh.”

“But Winter isn’t all cold and terrible. If you keep your wits about you and prepare for it, why, the Winter’ll be no real problem.” He leaned forward and raised his eyebrows at Cynthia. “The trick is, when Winter sets in, you have to have sense enough to know what you really need, and what you just think you want.” He pulled out his pouch and began filling the pipe. “Guess that’s what Winter’s for, to keep you sharp and alert and ready for the really hard times.”

“What could be harder than Winter?”

“Oh…the lonely times, when you have nobody to make you feel loved and needed. Or worse,” he went on, “when you have someone, but something keeps you apart. If you keep your head screwed on and know what you’re about, you can always keep your body warm. But when you’re cold inside, that’s another matter again.”

Cynthia thought again of the snow of her dream, freezing her heart. Cold inside, she thought. That’s why this Winter seems so much worse than any other.

“Winter can be a hardship,” the old man said, “make no mistake. The wind can blow mighty fierce,” and as if at a signal, the whistling wind grew to a roar, and Cynthia felt the coach rock with the force of it. “The snow can blow downright deadly,” the old man went on, and Cynthia almost expected an avalanche to sweep them off the tracks. “But life is full of hardships, and Winter is only one. The Book says, ‘Man is born to trouble as the sparks fly upward.’ The same goes for ladies, and even little girls like you, Cynthia.”

The surprise of hearing her name made Cynthia sit up straight. “Why did you call me that?”

The old man grinned. “I thought that was your name. Isn’t that what your mother called you?”

Cynthia relaxed a little, then knitted her brows in thought. Had Mother called her by name? She couldn’t remember.

The bearded stranger struck a match on the sole of his boot and lit his pipe. “Another thing about Winter,” he said between puffs, “and this is worth remembering: No matter how harsh the cold may be, it can never stamp out the warmth of new life.” He pointed out the sooty window. “In the very dead of Winter every twisted black twig sticking out of the frozen ground gives the promise of a sunny, green Spring.”

He cradled the tiny pipe in his hands and leaned forward. “You know, I believe that’s the reason we celebrate Christmas in the break of Winter. No matter when the Christ Child may really have been born, it helps us to recall the promise of New Life at the brink of the Season of Despair.” He sat back. “The spark burns low, but it never dies.”

Cynthia said, “You sure talk a lot about sparks and fire.”

The old man laughed a full, rolling laugh. “Do I?” he asked. “Why, I suppose I do. It must be the way I think. I spend a lot of time around sparks and soot and cinders.”

The words sounded odd to Cynthia. “What do you mean?”

“My pipe, of course,” he said, flicking a trace of ash off one thumb. “I never go anywhere without it. Spend half my time trying to keep it lit.”

Cynthia felt again the weight of Rose-Marie and the claws of the Winter monsters smothering her into ice. Suddenly she found herself talking almost without thinking, as if she had been asked what was on her mind. “I don’t think I want to spend Christmas in Seattle. Not if…not without…” She thought about the lovely porcelain doll in Barney Hart’s store, and about Papa. “Oh, I almost wish Christmas wouldn’t even come this year.”

“That’s only natural,” the old man said, “you want your family to be together. But Christmas comes whether you want it to or not.” He chuckled. “Don’t I know it.”

“I just wish…I don’t know.” Cynthia crossed her ankles and looked out the window for what seemed the thousandth time.

“What’s this?” the old man grinned, arching his thick white eyebrows. “A little girl so close to Christmas who doesn’t know what to wish for?” He puffed on his pipe and took out his notebook and pencil. As he wrote he added, “Children wish for so many things…”

Cynthia glanced at the notebook. “Something about the weather?”

“Eh?”

“What you’re writing?”

“Oh! No, just…” he closed the notebook and tucked it away. “Just a reminder to myself.” He puffed on his pipe and said, almost to himself, “So many things they wish for, especially at Christmastime. And nearly always for something foolish or pointless…”

That was when the thought finally came to Cynthia. I know what I really want for Christmas, she told herself, and it’s not pointless, not at all. It’s a perfectly sensible Christmas wish.

They sat and rode in a long smoky silence. The old man with the pink cheeks and white beard sat nibbling the stem of his pipe and stealing an occasional twinkling glance at Cynthia, who was quite lost in her own young, half-finished thoughts of Winter, Christmas, and her own mother and father.

At last the old man tamped out his pipe and put it away. “Your mother seems to be waking up,” he said. “I should take my gear and join my friend. We have things to talk over before we make Anchorage.”

The old man made his way to the front of the coach. Smiling, he said something, then bowed slightly to Cynthia’s mother as he retrieved his snowshoes and knapsack. Cynthia, still half-lost in thought, watched him as he headed back. As he got to Cynthia he set down his pack and extended his hand to her. Cynthia had never shaken hands with anyone before, and her fingers tingled at his dry, gentle touch.

“Merry Christmas, Cynthia,” he said. “I hope, I truly hope you get what you most want.” And then, before she could return his farewell or even thank him, the old man was gone.

Cynthia returned to her seat beside her mother. “What time is it, dear?” Mother asked with a yawn. “How long did I sleep?”

“I don’t know,” Cynthia said, still thinking. “I fell asleep too.”

Mother looked at the tiny watch that hung from a chain around her neck. “It’s late,” she said. “We’ll be there before long.” Mother’s eyes sparkled sadly as she stared into the darkness beyond the train window. Cynthia listened to the dying whistle of the wind, and wondered if Mother were also listening to hear the monsters.

* * *

The depot at Anchorage seemed vast to Cynthia, though she realized it probably wasn’t much beside one in New York, or Chicago, or even Seattle. I guess things are just going to start getting bigger and bigger, she thought.

Mother checked the trunk in the baggage room. Then she took Cynthia over to one of the depot benches. She took a handkerchief out of the carpet bag and dabbed at a spot of soot on Cynthia’s cheek, then straightened the bow at the collar of Cynthia’s dress. Then suddenly she bit at her lower lip and swept Cynthia into her arms and held her close. For a moment Cynthia was afraid Mother might cry, but she didn’t. “I’m so proud of you, darling,” she said, “I really am.” She had to straighten Cynthia’s bow again. “You’re just the most wonderful…” She bit her lip again. “Well. What we have to do now is go over to the shipping office and see when the next boat –” she took a short breath “– leaves for Seattle. Then we’ll decide what to do next. All right?” Cynthia nodded, and Mother stood up, taking her by the hand. “Good. You’ll like Seattle, dear. It’s a good place to spend Christmas.”

At that moment a man walked up to them and, to Cynthia’s surprise, addressed Mother by name. Cynthia could see from his green eyeshade and sleeve garters that he worked at the depot, and he carried a yellow envelope that he offered to Cynthia’s mother.

“This came over the wire for you this evening, ma’am,” he said, “shortly before your train arrived.”

Mother thanked him and opened the envelope; Cynthia noticed a look of worried confusion on her face. As Mother read the telegram her hand went to her mouth and her eyes filled with tears. She fell back onto the bench behind her and began to cry, sobbing in a way Cynthia had never seen before.

The station agent sat beside Mother, asking if she felt quite all right, and if the telegram were bad news. Mother sat, one hand wiping her cheeks, the other clutching the crumpled telegram, until her tears subsided. Then she took a deep breath, raised her head, and when she turned to face the man, the tears were gone.

“You’re very kind, thank you, but it’s not bad news.” She paused, and as she spoke again Cynthia heard her voice tremble just a little. “Sir,” she said, “can you direct me to a reasonable hotel in this city where my daughter and I can stay? My husband will be joining us in time for Christmas.”

For a moment Cynthia thought her heart would burst, and that she would start crying herself. But the moment passed and she contained herself — Mother had had enough of tears for one day. Instead, she stood there dazed as the station agent recommended a nearby hotel and took his leave of them.

When he was gone, Cynthia and her mother looked at each other and hugged each other again, a different hug, and for a second it seemed that they would start giggling like best friends.

“The next train from Fairbanks is in two days,” Mother said. “We have tomorrow to see Anchorage — and we may even have enough money to buy you a new hat to visit your grandparents. Do you think you’d like that?”

“Oh, Mother, I would,” Cynthia said, “I know I would.” And with lighter hearts they went to have their trunk sent to the hotel.

Cynthia spotted the bearded old man before she realized she was looking for him. He was not hard to find; as Cynthia expected, he was leaving the station with the little nutcracker-faced man who had shared his campfire in her dream. She told her mother she wanted to say goodbye, and that she wouldn’t be long, and ran off, with Mother calling after her to be careful and not go too far.

The old man must have heard her coming, because he turned to face her as she ran up to him. She stood there, a little out of breath, and said, “We got a telegram. Papa’s coming on the next train. We’re all going to Seattle together.”

The old man smiled broadly. “Well, now,” he said, “I’m right glad to hear it. Maybe this Winter won’t be as bad as you thought, eh?”

The little man beamed. “You must be Cynthia,” he said. “I’m Amos.” He held out his hand, and for the second time in her life Cynthia shook hands. This time the little man’s hand disappeared into hers.

“What hotel are you staying at?” she asked. “Maybe we’ll be neighbors.”

The old man and Amos laughed. “We won’t be staying anywhere for a while,” the old man said. “Amos and I have a lot of fish to fry in the coming days, and no time to dawdle.”

Something occurred to Cynthia. “I thought you’d be surprised,” she said, “but you weren’t. Not at all. You knew Papa was coming, didn’t you?”

The old man shrugged. “I didn’t know. But I’ve met you and your mother. I wasn’t surprised.”

There was another silence between them. Cynthia spoke first.

“Who are you?”

The old man exchanged a glance with Amos, then set his pack down and lowered himself to one knee in front of Cynthia. He took one of her hands and held it in both of his.

“Cynthia,” he said, softly, tenderly, “I’m nobody at all. Just a fat old man who doesn’t like to shave. You think you see something of Christmas in me and Amos, and that’s only right. You’re a little girl, and at this time of year Christmas should be everywhere you look. Just remember what I said: The spark burns low, but it never dies. Let Christmas be everywhere you look and the harshest Winter will never be cold or hopeless again.”

Cynthia looked from the broad bearded face of the old man to Amos’s crinkled grin. For what seemed a long moment the two men smiled at her warmly, with a sly twinkle lighting up their eyes, and in that moment Cynthia knew — beyond knowing — who this white-haired, cheerful old gentleman was. And she knew there was truth — beyond truth — in everything he told her.

She threw her arms around the old man’s neck and hugged him. “Merry Christmas,” she said. “And…thank you.” She looked at Amos. “Thank you both.”

Amos gave her a quizzical look, as if he didn’t understand, but the old man just patted her arm. “Any time,” he said. He stood up and hoisted his knapsack. “Tell your mother I wished her a Merry Christmas too,” he said. “And your father when you see him.”

“I will.”

The old man and Amos smiled at her once more, then turned and walked away into the Anchorage night. Just before they were out of sight, Amos looked around and waved to her, and Cynthia waved back. Then she headed back into the station to join her mother, as the Fairbanks train sat still wheezing and coughing after its long climb down out of the snowy Alaskan forest.

THE END

As you might expect, this made for quite a mixed bag: Neptune Nonsense (1936), a Felix the Cat cartoon (in Technicolor for a change) in which Felix gets in trouble with King Neptune when he tries to “fishnap” a companion for his lonely goldfish at home; Daffy Duck in Hollywood (1938), where the duck at his daffiest crashes the gates at Warner Bros. and revolutionizes the movie business; Ground Hog Play, a Casper the Friendly Ghost toon from 1956 (personally, I could always take but would prefer to leave Casper alone); and so on.

As you might expect, this made for quite a mixed bag: Neptune Nonsense (1936), a Felix the Cat cartoon (in Technicolor for a change) in which Felix gets in trouble with King Neptune when he tries to “fishnap” a companion for his lonely goldfish at home; Daffy Duck in Hollywood (1938), where the duck at his daffiest crashes the gates at Warner Bros. and revolutionizes the movie business; Ground Hog Play, a Casper the Friendly Ghost toon from 1956 (personally, I could always take but would prefer to leave Casper alone); and so on. Last year at Cinevent, the Saturday animation program was followed by producer George Pal’s Houdini (1953) with Tony Curtis and Janet Leigh, which took me back to my childhood and the kiddie matinees at the Stamm Theatre in Antioch, Calif. There was more than one Saturday, and probably more than two, when an hour-and-a-half of cartoons was followed by Houdini. Well, danged if I didn’t get exactly that same sense of déjà vu this year — another passel of cartoons, another George Pal. This time it was When Worlds Collide (1951), from the 1932 Edwin Balmer/Philip Wylie novel about two rogue planets on a collision course with Earth, and the desperate efforts to build a spaceship to transport a sampling of humanity to one of the (apparently habitable) planets before the home world is obliterated.

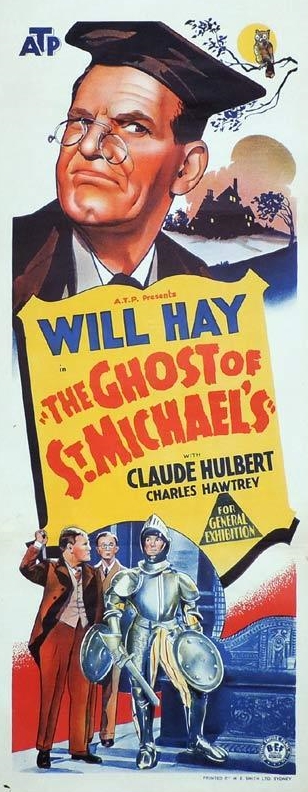

Last year at Cinevent, the Saturday animation program was followed by producer George Pal’s Houdini (1953) with Tony Curtis and Janet Leigh, which took me back to my childhood and the kiddie matinees at the Stamm Theatre in Antioch, Calif. There was more than one Saturday, and probably more than two, when an hour-and-a-half of cartoons was followed by Houdini. Well, danged if I didn’t get exactly that same sense of déjà vu this year — another passel of cartoons, another George Pal. This time it was When Worlds Collide (1951), from the 1932 Edwin Balmer/Philip Wylie novel about two rogue planets on a collision course with Earth, and the desperate efforts to build a spaceship to transport a sampling of humanity to one of the (apparently habitable) planets before the home world is obliterated. After the lunch break I had a chance to plug one of those gaps in my movie experience that has always kind of bugged me: I finally got to see a Will Hay movie, The Ghost of St. Michael’s (1941).

After the lunch break I had a chance to plug one of those gaps in my movie experience that has always kind of bugged me: I finally got to see a Will Hay movie, The Ghost of St. Michael’s (1941).

A surprise hit on Friday was

A surprise hit on Friday was  There were other pleasures on the bill on Friday:

There were other pleasures on the bill on Friday:  There was a certain amount of backstage drama this year as the 49th Annual Cinevent Classic Film Convention gathered in Columbus, Ohio over Memorial Day Weekend, and for a while it threatened to throw a bit of a monkey wrench into the program. But never mind, the drama resolved itself with a minimum of fuss and things proceeded more or less as planned.

There was a certain amount of backstage drama this year as the 49th Annual Cinevent Classic Film Convention gathered in Columbus, Ohio over Memorial Day Weekend, and for a while it threatened to throw a bit of a monkey wrench into the program. But never mind, the drama resolved itself with a minimum of fuss and things proceeded more or less as planned.

Just before the dinner break came Laurel and Hardy’s immortal

Just before the dinner break came Laurel and Hardy’s immortal

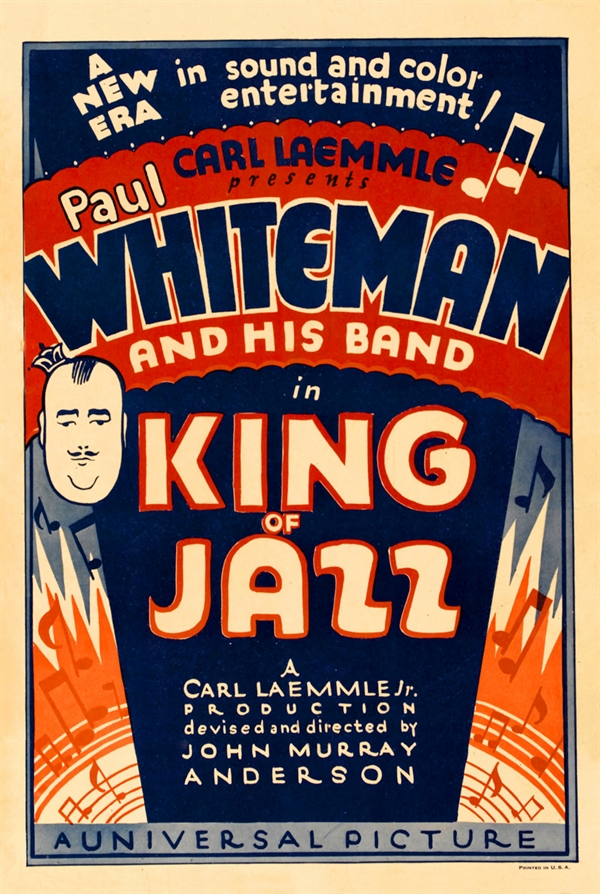

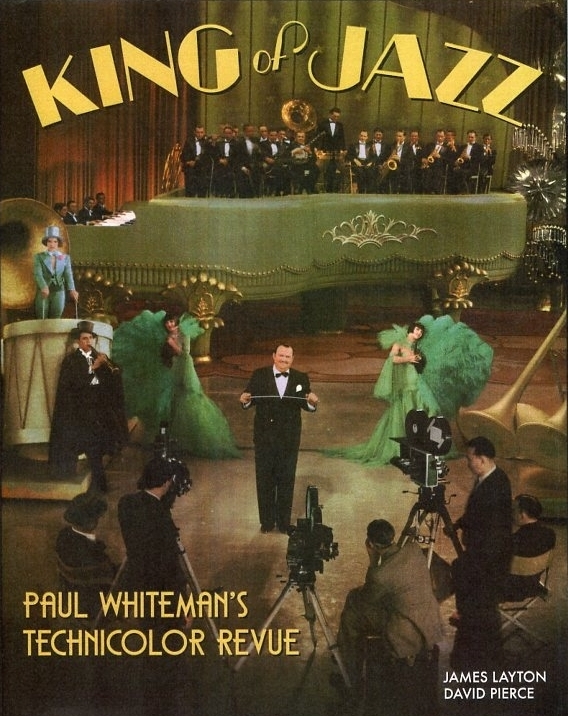

Scroll down to see, if you haven’t seen it already, my two-part tribute to Universal Pictures’ King of Jazz (1930). This epilogue is for the benefit of Cinedrome readers who live within traveling distance of Sacramento, Calif. I’ve got big news, and the news is this:

Scroll down to see, if you haven’t seen it already, my two-part tribute to Universal Pictures’ King of Jazz (1930). This epilogue is for the benefit of Cinedrome readers who live within traveling distance of Sacramento, Calif. I’ve got big news, and the news is this: If John Murray Anderson had been on board from the get-go, and if production had begun promptly once Paul Whiteman was signed in October 1928, King of Jazz might have caught the crest of the studio-revue wave as talkies came in, instead of sinking in the undertow as the wave rolled out. At the very least, the picture’s astronomical costs would have been only a fraction of what they were — even with Technicolor and Herman Rosse’s spectacular sets (which won him an Oscar for 1929-30). That in turn would have made King of Jazz‘s profit threshold a lot lower; in all likelihood, the picture would have cost less and earned more. But such was not to be. King of Jazz’s big splash turned into a belly-flop, and it sank like a rock.

If John Murray Anderson had been on board from the get-go, and if production had begun promptly once Paul Whiteman was signed in October 1928, King of Jazz might have caught the crest of the studio-revue wave as talkies came in, instead of sinking in the undertow as the wave rolled out. At the very least, the picture’s astronomical costs would have been only a fraction of what they were — even with Technicolor and Herman Rosse’s spectacular sets (which won him an Oscar for 1929-30). That in turn would have made King of Jazz‘s profit threshold a lot lower; in all likelihood, the picture would have cost less and earned more. But such was not to be. King of Jazz’s big splash turned into a belly-flop, and it sank like a rock.

So let’s recap: By the end of 1933, there had been a total of some 11 distinctly different versions of King of Jazz (or El Rey del Jazz, Král jazzu, Der Jazzkönig, La Féerie du Jazz, Kingu Obu Jazu, etc.) playing somewhere on the globe at one time or another. This confusing plethora of source material would present quite a challenge 80-plus years later, when NBCUniversal undertook to restore the picture in 2015.

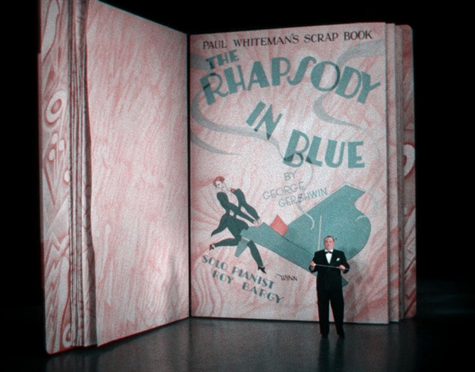

So let’s recap: By the end of 1933, there had been a total of some 11 distinctly different versions of King of Jazz (or El Rey del Jazz, Král jazzu, Der Jazzkönig, La Féerie du Jazz, Kingu Obu Jazu, etc.) playing somewhere on the globe at one time or another. This confusing plethora of source material would present quite a challenge 80-plus years later, when NBCUniversal undertook to restore the picture in 2015. It’s this VHS version that has been in circulation for 33 years (never available on DVD except in various bootlegs), and on which my own fondness for King of Jazz has always rested. (The picture here, and the shot of the Russell Markert Girls in Part 1, are frame-caps from it.) Now I learn that this was (in Layton and Pierce’s words) “a bastardized version…a mishmash of the 1930 and 1933 releases compiled to create the longest possible cut.” And at that, it still runs only 91 minutes.

It’s this VHS version that has been in circulation for 33 years (never available on DVD except in various bootlegs), and on which my own fondness for King of Jazz has always rested. (The picture here, and the shot of the Russell Markert Girls in Part 1, are frame-caps from it.) Now I learn that this was (in Layton and Pierce’s words) “a bastardized version…a mishmash of the 1930 and 1933 releases compiled to create the longest possible cut.” And at that, it still runs only 91 minutes. Seen today — and I speak, of course, from familiarity with the “bastardized” VHS release — King of Jazz remains an embarrassment of riches. Some, admittedly, are richer than others, while some are chiefly of historical interest as examples of the kind of comedy and novelty performances that died with vaudeville. Several of the more impressive set pieces — for example, “My Bridal Veil”, a pageant of wedding attire from different historical eras from the 1550s to the 1920s, and “Rhapsody in Blue” itself — are film versions of shows John Murray Anderson staged for Paramount Publix Theatres. As such, they are of keen interest to those of us who know about such prologues only from what we can see in Footlight Parade. To see these extravaganzas in the flesh must really have been a knockout; to see them now in Technicolor is a real trip in the time machine.

Seen today — and I speak, of course, from familiarity with the “bastardized” VHS release — King of Jazz remains an embarrassment of riches. Some, admittedly, are richer than others, while some are chiefly of historical interest as examples of the kind of comedy and novelty performances that died with vaudeville. Several of the more impressive set pieces — for example, “My Bridal Veil”, a pageant of wedding attire from different historical eras from the 1550s to the 1920s, and “Rhapsody in Blue” itself — are film versions of shows John Murray Anderson staged for Paramount Publix Theatres. As such, they are of keen interest to those of us who know about such prologues only from what we can see in Footlight Parade. To see these extravaganzas in the flesh must really have been a knockout; to see them now in Technicolor is a real trip in the time machine. I’ve always had a tremendous fondness for King of Jazz (1930).

I’ve always had a tremendous fondness for King of Jazz (1930). This disconcerting knowledge comes to me courtesy of a sumptuous, stunning new book,

This disconcerting knowledge comes to me courtesy of a sumptuous, stunning new book,

Finally, exit Paul Fejos and enter John Murray Anderson. Anderson, 43 in 1929, was one of the acknowledged masters (perhaps even the preeminent one) of the musical revue, having first made his mark with The Greenwich Village Follies, which moved from Sheridan Square to Broadway in 1919. The show packed ’em in for months and led to annual sequels for the next six years, then a final edition in 1928. Anderson’s hallmarks were taste, artistry and technical innovation on a modest budget.

Finally, exit Paul Fejos and enter John Murray Anderson. Anderson, 43 in 1929, was one of the acknowledged masters (perhaps even the preeminent one) of the musical revue, having first made his mark with The Greenwich Village Follies, which moved from Sheridan Square to Broadway in 1919. The show packed ’em in for months and led to annual sequels for the next six years, then a final edition in 1928. Anderson’s hallmarks were taste, artistry and technical innovation on a modest budget. There was dancing, too. Most prominent in this area was a group of 16 high-kicking precision tappers then known as the Russell Markert Girls; in time this ensemble would come to be known as the Rockettes — first at New York’s 5,900-seat Roxy Theatre, then at Radio City Music Hall, where the group continues to this day. King of Jazz was, for them as for Bing Crosby, their movie debut.

There was dancing, too. Most prominent in this area was a group of 16 high-kicking precision tappers then known as the Russell Markert Girls; in time this ensemble would come to be known as the Rockettes — first at New York’s 5,900-seat Roxy Theatre, then at Radio City Music Hall, where the group continues to this day. King of Jazz was, for them as for Bing Crosby, their movie debut.