I now return to my too-long-dormant series commemorating the movies of Henry Hathaway, my personal nominee for the most neglected and underrated director of the Golden Age of Hollywood.

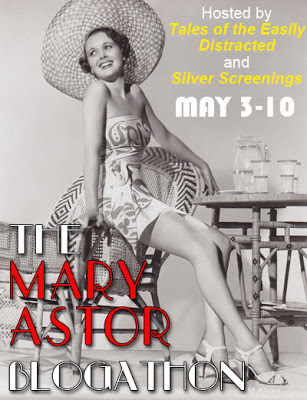

But this post is more than that. It’s also Cinedrome’s contribution to The Mary Astor Blogathon, co-hosted by my Classic Movie Blog Association colleagues Dorian of Tales of the Easily Distracted and Ruth of Silver Screenings. Click on the first link in this paragraph for a list of other entries in the blogathon, and on the other two links for a more general entry into Dorian and Ruth’s excellent blogs — a lot of great stuff there! (This blogathon, by the way, celebrates the 107th anniversary of Ms. Astor’s birth, born Lucile Vasconcellos Langhanke on May 3, 1906.)

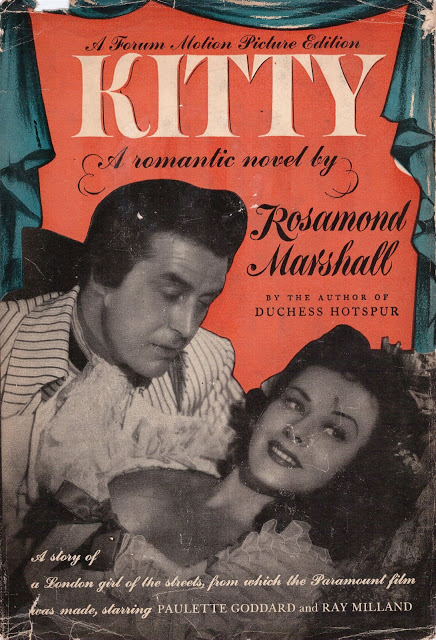

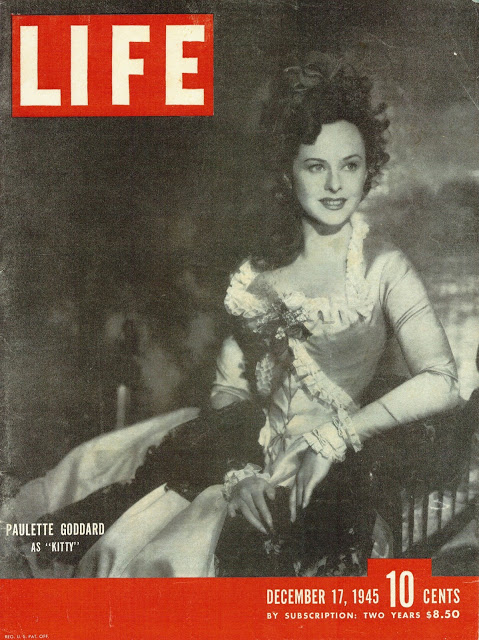

Mary Astor was an actress of remarkable versatility, which she demonstrated time and again in the course of her 43-year screen career. That point is amply illustrated by this image for the blogathon, since nothing could be more different from the Mary Astor you see here than the one you’ll see in the movie I’ve chosen for the subject of this post…

* * *

“Darryl,” Henry Hathaway said when Darryl F. Zanuck borrowed him from Paramount to direct Brigham Young, “the two dullest things in the whole world are a wagon train and religion. Now you take them and put them together.”

“This man Brigham Young,” Zanuck replied, “is more important than the story.”

Zanuck first became interested in filming the story of the “Mormon Moses” in 1938, at the suggestion of 20th Century Fox staff writer Eleanor Harris and with the encouragement of novelist Louis Bromfield, whom Zanuck hired to write a screen story for another Fox staffer, Lamar Trotti, to turn into a script.

(A side note on Louis Bromfield: In 1940 he was one of the most famous writers in America, considered the peer of Faulkner, Hemingway and Fitzgerald; notice that he receives authorial pride of place on the title card for Brigham Young, in type even larger than that for Zanuck himself. Nearly all of his 30-plus books were bestsellers, and he won a 1927 Pulitzer Prize for his third novel, Early Autumn. In his day he was a prime example of the Literary Man as Celebrity: Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall were married at his Ohio farm in 1945. Alas, when he died in 1956 it was almost as if every one of his readers had died with him, and he is largely — and unfairly — forgotten today. A number of his books were made into memorable movies, and I may be posting on some of them in time to come.)

Although the title of the picture was Brigham Young, top billing went to Tyrone Power and Linda Darnell as two fictitious characters created by Bromfield and Trotti. Power was cast as Jonathan Kent, a young non-Mormon “outsider” who ends up scouting for Brigham Young and his followers on their trek west, while Darnell was to play Zina Webb, a Mormon girl with whom he falls in love.

Originally slated to direct Brigham Young was Fox contract director Henry King, the studio’s specialist in historical pictures and atmospheric Americana. King had already directed such Fox pictures as State Fair (1933), Ramona and Lloyds of London (both ’36), In Old Chicago (’37), Alexander’s Ragtime Band (’38), and Jesse James and Stanley and Livingstone (both ’39). (Several of those had starred Tyrone Power, although Power had yet to be cast in Brigham Young.) It seemed a natural fit, but for some reason the deal with King fell through. James D’Arc, in his commentary on the Brigham Young DVD, says that he could find no documentation in the Fox archives explaining this. I think it’s just possible — and I hasten to emphasize that this is the purest speculation on my part — that King, a Catholic, was uncomfortable with the Mormon story. I have absolutely no evidence for this, but it strikes me as the sort of thing that wouldn’t necessarily be committed to paper.

In any case, whatever the reason, in January 1940 Zanuck arranged to borrow Henry Hathaway from Paramount to direct the picture. That was when Hathaway made the remark that opens this post; it was also when Hathaway suggested changing the religious orientation of the two star characters: make Jonathan Kent the Mormon and Zina Webb the outsider. Zanuck agreed, and Hathaway (at his own expense) brought in Grover Jones, who had worked with him on Lives of a Bengal Lancer (’35) and The Trail of the Lonesome Pine (’36), among others, to write the change into the script. (Lamar Trotti, Hathaway later said, was incensed, and didn’t speak to the director for the rest of his life.)

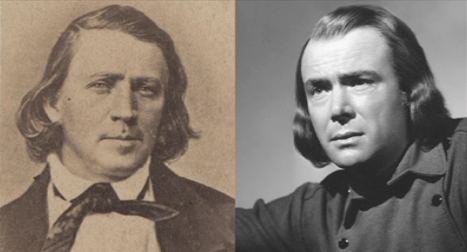

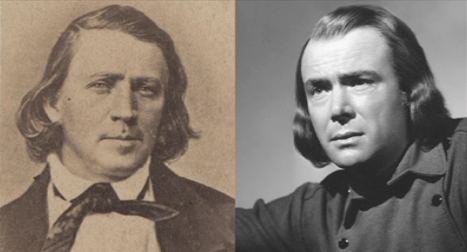

For the all-important role of Brigham Young himself, Zanuck waffled. He considered Spencer Tracy, Don Ameche, Walter Huston, Albert Dekker, even Clark Gable (assuming he could be borrowed from MGM). But all, it seemed to Zanuck, had too-well-established screen personae. Zanuck even halted pre-production while he wrestled with the question. In the end, he went out on a limb, casting Dean Jagger, who had been rattling around Hollywood as a freelance actor since 1929 without making much of an impression. As this dual portrait shows (that’s the real Brigham, circa 1850, on the left), Jagger’s resemblance to Young was striking. Serving as technical advisor on the picture was 79-year-old George Pyper, a Salt Lake City theater buff and manager of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir. As a young man, Pyper had known Brigham Young personally (just think about that for a moment), and he had this to say in 1940: “Besides resembling him in appearance, there’s also a striking similarity to voice. I was only 17 when Brigham Young died, but I had known him well. Mr. Jagger even has some of Brigham’s mannerisms and his walk.”

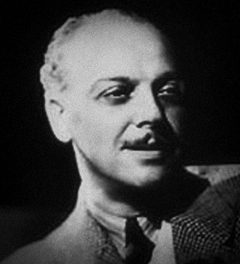

Joseph Smith, the founder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, was played by Vincent Price, then in the third year of his movie career (Brigham Young was only the eighth of his 199 film and TV credits). The role was merely a supporting one — almost a cameo, considering the major star Price would become — since it was Smith’s murder by a lynch mob on June 27, 1844 that propelled Brigham Young to leadership of the Mormon Church. Hathaway later remembered that he insisted on Price for the role: “He seemed just right — so ethereal.” In a 1972 letter to James D’Arc, Price wrote: “I think one interesting sidelight was the wonderful direction of Henry Hathaway — how he avoided any ‘religious’ feeling and made it a believable story of strong men and women fighting for their faith. He was particularly vehement on this score with the part of Joseph. There was to be no hint of the standard Christ image — rather he felt Joseph was the interpreter of God’s word and as such should not wear a halo.”

A fictitious character was Angus Duncan, played by Brian Donlevy (shown here on the right with Frank Thomas as Hubert Crum, also fictitious; Donlevy was even considered — ever so briefly, and probably not seriously — for the part of Brigham). In Trotti’s script, Duncan rivals Brigham Young for leadership in the wake of Joseph Smith’s murder. In fact, Young had no serious rival in the eyes of most of Smith’s followers, although a few men siphoned off some believers into splinter sects of their own. Angus Duncan is the voice of dissent within the Mormon ranks, at first — while Smith is still alive — advocating for craven surrender in the face of the Mormon Church’s frontier persecutors. When Duncan stands in council and whimpers “Just give them whatever they want so we can have peace!”, audiences of 1940 were clearly expected to remember Neville Chamberlain on the London tarmac after surrendering to Adolf Hitler at Munich. Later, as Brigham Young leads the Latter-day Saints on their westward exodus, Duncan becomes a 19th century American version of the Old Testament figure of Dathan, who rebelled against Moses (the Edward G. Robinson role in Cecil B. DeMille’s 1956 The Ten Commandments). Even the names are similar: Duncan; Dathan. Duncan is forever second-guessing and carping at Brigham (“I told you what would happen if we settled in this valley, but you wouldn’t listen to me! You ran off with a false prophet!”). At one point on the trail, he even hears talk from an eastbound traveler about gold in California (an anachronism; gold wasn’t discovered till more than a year after it happens in the movie), Duncan then passes the gossip off as a revelation from God, hoping to lead the Mormons astray — in a real sense, offering them a Golden Calf (an analogy the script makes explicit).

Mary Astor played Mary Ann Young, Brigham’s senior wife. It was a tricky assignment, because of course Mary Ann wasn’t the only one. (In fact, on the right in this picture is Jean Rogers as Clara, Wife No. 2.) Long before 1940, the Mormons had renounced polygamy, but it was still one of the main things people associated with the early church, and Brigham Young handled the subject gingerly. An anti-Mormon yahoo makes a crude joke about “50 wives”. When, on their westward migration, the Mormons stop at Fort Bridger, Brigham has a conversation with the famous scout Jim Bridger, who asks, “Say, how many…” Brigham cuts him off: “Twelve.” And the conversation quickly switches to other things. Later, in a fireside chat with Mary Ann, Brigham praises her: “Sometimes I don’t know what I’d do without you. Always the same, never complaining, never jealous of the others…” Others? An inattentive viewer (which I certainly was when I first saw Brigham Young as a child) would think Mary Ann was Brigham’s only wife. Jean Rogers gets screen credit but speaks hardly a line of dialogue, and there are occasional shots of other young women riding in or walking alongside the Young wagon, but in terms of the dramatic action of the movie, Mary Ann speaks and acts for them all. Here’s James D’Arc in his DVD commentary:

“As Mary Ann, [Astor] is pivotal in bolstering Brigham in his doubts, in the midst of his almost unbearable responsibility. Hers is a strong presence, decisive, practical and unsentimental. She prays that God will talk to him, even as she encourages Brigham with her love and support.”

The only other mention of polygamy — and in fact the only sustained one — comes in two later scenes (90 min. into the 112 min. picture). First, Jonathan Kent proposes marriage to Zina Webb, and she scornfully wonders how many more he’s going to ask, and how he plans to go about it: “Just imagine, 30 wives combing your beard!” This scene was obviously written by Grover Jones, since in Trotti’s original script it was Zina and not Jonathan who was the Mormon (how the proposal would have been treated if Hathaway hadn’t suggested the change is anybody’s guess).

Immediately after, there’s a scene between Jonathan and Porter Rockwell (a historical figure played by John Carradine) where the two humorously discuss the possible population boom under plural marriage, Rockwell saying, “I’m aimin’ to do my share.” And with that, the subject is closed for the remainder of the movie.

Other events in early Mormon history were treated more fully and dramatically. The picture begins with a nightrider raid on the Kent homestead during a party. Jonathan’s father is beaten to death, and even Zina’s father is shot dead — even though he’s not a Mormon himself, just somebody being friendly with the wrong people at the wrong time. This and later scenes of the persecution of Mormons had clear parallels — which Trotti’s script underscored — in Nazi Germany’s treatment of Jews. The Holocaust was still in the future, but pogroms like Kristallnacht were already on record; Zanuck even referred to raids like this in 1840s Ohio, Missouri and Illinois as “pogroms”.

In the movie, Joseph Smith is tried and convicted of treason. The trial is fictional; actually, Smith was awaiting trial when he was murdered. But it dramatizes the rabid anti-Mormon sentiment of the time in the raving denunciations of the prosecutor (Marc Lawrence) and the unhesitating “guilty” verdict of the jury. It also allows Brigham Young to address the court, describing his first meeting with Joseph Smith (shown in flashback) and delivering a ringing endorsement of freedom of religion: “You can’t convict Joseph Smith just because he happens to believe something you don’t believe. You can’t go against everything your ancestors fought and died for. And if you do, your names, not Joseph Smith’s, will go down in history as traitors. They’ll stink in the records, and be a shameful thing on the tongues of your children.” (In fact, during the events that led up to Smith’s killing, Young was in Massachusetts spreading the word and recruiting converts.) After the trial, a resigned Smith implicitly transfers care of his flock to Young — “I want you to stay and take care of my people.” — before being led off with his brother Hyrum (Stanley Andrews, the “Old Ranger” of TV’s Death Valley Days). Later, the mob murder of Hyrum and Joseph is shown pretty much as it happened that night in Carthage, Ill.

In the movie, Joseph Smith is tried and convicted of treason. The trial is fictional; actually, Smith was awaiting trial when he was murdered. But it dramatizes the rabid anti-Mormon sentiment of the time in the raving denunciations of the prosecutor (Marc Lawrence) and the unhesitating “guilty” verdict of the jury. It also allows Brigham Young to address the court, describing his first meeting with Joseph Smith (shown in flashback) and delivering a ringing endorsement of freedom of religion: “You can’t convict Joseph Smith just because he happens to believe something you don’t believe. You can’t go against everything your ancestors fought and died for. And if you do, your names, not Joseph Smith’s, will go down in history as traitors. They’ll stink in the records, and be a shameful thing on the tongues of your children.” (In fact, during the events that led up to Smith’s killing, Young was in Massachusetts spreading the word and recruiting converts.) After the trial, a resigned Smith implicitly transfers care of his flock to Young — “I want you to stay and take care of my people.” — before being led off with his brother Hyrum (Stanley Andrews, the “Old Ranger” of TV’s Death Valley Days). Later, the mob murder of Hyrum and Joseph is shown pretty much as it happened that night in Carthage, Ill.

The next great dramatic set piece in Brigham Young is the exodus from Nauvoo, Ill. in the face of mounting hostility. It also occasions the first open conflict between Brigham and Angus Duncan. Like Moses in the Book of Exodus, Brigham prevails, and the Mormons light out on their trek by crossing the ice of the frozen Mississippi. Again, dramatic license is taken. The Mormons set out over a period of weeks in February 1846, not in a single night, and the Mississippi, though filled with ice, wasn’t quite frozen enough to bear the wagon train like this. But with the Mormons escaping from a band of vigilantes hot on their heels, it makes a dramatic parallel to the Israelites fleeing from Pharaoh’s army through the parted Red Sea.

This spectacular shot, by the way, was the work of special effects genius Fred Sersen. Director Hathaway had nowhere near that number of wagons at his disposal; the building and maintaining of Conestoga wagons was an all-but-lost art by 1940, to say nothing of finding and feeding the horses and oxen to pull them. Most studios had no more than a handful of wagons in their rolling stock, which had to be cleverly filmed and edited to swell their numbers. Many scenes of the westward trek in Brigham Young were enhanced by the use of stock footage from Raoul Walsh’s early sound epic The Big Trail, one of the last pictures to amass Conestoga wagons in anything like the numbers suggested here. (The Big Trail, a legendary box-office dud in 1930, holds up quite well today, and rates a post of its own.)

The climax of Brigham Young comes, not surprisingly, in the spring of 1848. After a grueling and disastrous winter of 1847-48, when the Mormon settlement in the Great Salt Lake Valley faced starvation that threatened to decimate their numbers — if not annihilate them entirely — things are beginning to look up with the spring planting. Then, a new disaster. A sudden infestation of crickets arrives to wipe out their crops. This scene was shot in Elko, Nev., where just such an invasion (at the time, anyhow) occurred like clockwork every few years. Hathaway and the company flew to Elko and waited. Just as they were getting impatient — “Don’t they know they’re holding up the schedule?” — the crickets arrived, and it was a nightmare as much for the company as it had been for the Mormons in 1848. Mary Astor left vivid descriptions in both her volumes of memoirs: the ugly bugs, countless millions of them, the size of her thumb, the piles of them as much as a foot high, the stench as they died and rotted in the 110-degree heat. The scene was scheduled to be shot over four days, but after one horrible day the cast and crew were in revolt; the hell with the money, they were going home. Hathaway and Grover Jones put their heads together, combining, shifting, telescoping. Finally Hathaway assembled the company, promising to wrap things by noon the next day if everybody would knuckle down and go to it. They didn’t make noon, but by four p.m., with heroic efforts, they were done.

In the movie, just as the Mormon despair matches that of their 1940 portrayers, comes…

…the famous Miracle of the Seagulls, a sky-blotting flight of birds that, in the words of one Mormon of the 1840s, came “sweep[ing] the crickets as they go”, devouring the insects and saving the settlers’ crops.

Again, some dramatic license here. Where in history the cricket invasion had descended on the settlement for several days, to be followed by two weeks of the saving intervention of the seagulls, the movie has the whole thing, crickets and seagulls both, occurring on the same frantic day, set to the stirring strains of Alfred Newman’s epic score. (In a nicely subliminal touch, the theme Newman used to score the arrival of the crickets was a variation on the music he used to accompany the nightrider raid on the Kent homestead at the opening of the picture.)

The scene of the seagulls, like this shot here, is another example of Fred Sersen’s work, combining images of the company on location at Lone Pine, Cal., with footage of seagulls shot months earlier at Utah Lake near Provo.

And finally, it must be said that in point of historical fact, Brigham Young wasn’t there for the Miracle of the Seagulls; he was off to the east arranging for the safe passage of later Mormon settlers, and he only heard of his followers’ miraculous deliverance by letter from his deputies on the scene. For a movie, of course, this would never do; Dean Jagger’s Brigham — along with Mary Ann, and Jonathan and Zina, and even the ankle-biting Angus Duncan — had to be on hand, right there in what would one day be Salt Lake City, Utah, reveling in the divine vindication of Brigham Young’s leadership, which had brought him and his followers across a thousand miles of hostile prairie to their Promised Land.

After its premiere in Salt Lake City, Brigham Young underwent a title change for its general release, becoming Brigham Young — Frontiersman. This is how it appeared in reviews and publicity, and on posters and lobby cards, as a way of emphasizing the pioneer rather than religious aspect of the story. But it never appeared that way on screen, as the title card that begins this post attests. Now, the “Frontiersman” is gone for good, having presumably served its purpose, and Brigham Young again bears, in all labeling and packaging, the title under which it premiered in Salt Lake City on August 23, 1940.

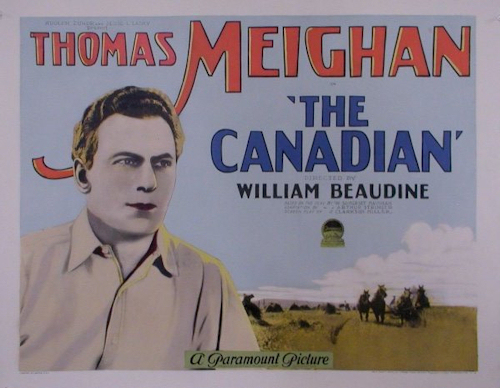

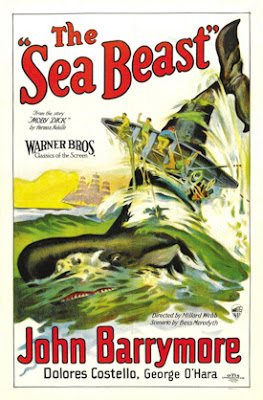

Upstaging The Sea Beast, and just about everything else shown at Cinevent this year, was a real discovery, an absolute bolt out of nowhere, a picture almost nobody had ever heard of. It was The Canadian (1926), directed by none other than William Beaudine. Yes, the notorious “One-Shot” Beaudine, who cranked out some 368 features, shorts and TV episodes over his 53-year career — including the sexploitation “documentary” Mom and Dad (’45) and, towards the end of his run, the camp titles Billy the Kid Vs. Dracula and Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter (both ’66). But back in the ’20s, Beaudine was a director to reckon with, and The Canadian shows why. It’s a simple story: Young Englishwoman Nora Marsh (Mona Palma) is left penniless at the death of the aunt she’s been living with, and has no choice but to emigrate to Canada, where her brother is a struggling farmer on the frontier of western Ontario. Pampered, stuck-up and generally useless, Nora clashes with her brother’s no-nonsense wife, until at length the wife lays down an either-she-goes-or-I-go ultimatum. Nora impulsively marries Frank Taylor, a neighboring farmer (Thomas Meighan), and the rest of the picture tells how this prissy little snob learns to carry her weight in her new household, where she and her stranger/husband slowly grow to love each other.

Upstaging The Sea Beast, and just about everything else shown at Cinevent this year, was a real discovery, an absolute bolt out of nowhere, a picture almost nobody had ever heard of. It was The Canadian (1926), directed by none other than William Beaudine. Yes, the notorious “One-Shot” Beaudine, who cranked out some 368 features, shorts and TV episodes over his 53-year career — including the sexploitation “documentary” Mom and Dad (’45) and, towards the end of his run, the camp titles Billy the Kid Vs. Dracula and Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter (both ’66). But back in the ’20s, Beaudine was a director to reckon with, and The Canadian shows why. It’s a simple story: Young Englishwoman Nora Marsh (Mona Palma) is left penniless at the death of the aunt she’s been living with, and has no choice but to emigrate to Canada, where her brother is a struggling farmer on the frontier of western Ontario. Pampered, stuck-up and generally useless, Nora clashes with her brother’s no-nonsense wife, until at length the wife lays down an either-she-goes-or-I-go ultimatum. Nora impulsively marries Frank Taylor, a neighboring farmer (Thomas Meighan), and the rest of the picture tells how this prissy little snob learns to carry her weight in her new household, where she and her stranger/husband slowly grow to love each other.

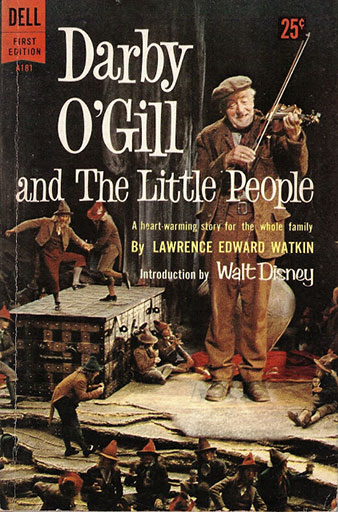

In 1962, if I had known that the actor playing James Bond was the same actor who played Michael McBride in Darby O’Gill and the Little People, I might have taken the trouble to see Dr. No sooner than I did. But in all the publicity surrounding the screen debut of Ian Fleming’s secret agent, and the handsome young discovery of producers Harry Saltzman and Albert Broccoli, there was scant mention (if any) of the picture Sean Connery had made for Walt Disney three years earlier. Small wonder: Darby O’Gill was a flop.

In 1962, if I had known that the actor playing James Bond was the same actor who played Michael McBride in Darby O’Gill and the Little People, I might have taken the trouble to see Dr. No sooner than I did. But in all the publicity surrounding the screen debut of Ian Fleming’s secret agent, and the handsome young discovery of producers Harry Saltzman and Albert Broccoli, there was scant mention (if any) of the picture Sean Connery had made for Walt Disney three years earlier. Small wonder: Darby O’Gill was a flop.