The murder came right smack in between Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle’s second and third trials, up in San Francisco, in the death of Virginia Rappe after a Labor Day party in Arbuckle’s suite at the St. Francis Hotel. And the press pounced on Taylor as they had on Arbuckle; here was more proof — as if any was needed — of the moral turpitude of Hollywood. Lurid stories circulated in the press as the investigation progressed. Most of them weren’t reflected in the official police files or those of a succession of Los Angeles district attorneys, but they were enough to ruin two careers.

Not all of those lurid stories were untrue. For one thing, it developed that William Desmond Taylor wasn’t his real name. He was born William Cunningham Deane-Tanner in 1872, not 1877 as was widely believed while he was alive. He had abandoned a wife and daughter in New York in 1908; his wife had divorced him in absentia, but she spotted him in one of his pictures as an actor, leading his daughter Daisy to seek to contact him. They had finally met in July 1921, and Tanner/Taylor promised to see her again; as things turned out, he never did. There was enough mystery in Taylor’s real life to feed plenty of rumors after his death.

The first career ruined by the Taylor scandal belonged to Mabel Normand. Already “tainted” in the public mind by her long on-screen association with Arbuckle, she had the incredibly bad luck to be the last person (besides the killer) to see Taylor alive. She had visited him that night, leaving a little after 7:30; Taylor walked her out to her car on Alvarado, then returned to his house for the last time. Rumors were repeated in the press: that she was a cocaine addict (true); that she was back at Taylor’s the morning his body was discovered, ransacking the place in search of compromising letters (false). She was closely questioned, investigated and exonerated. But it didn’t help; the rumors — and her drug problem — persisted, and fed each other in a spiraling decline. By the time she died in 1930, of tuberculosis no doubt aggravated by her addiction, she hadn’t worked in three years. She was only 37. As she lay dying, it’s said, she mused, “I wonder who killed poor Bill Taylor.”

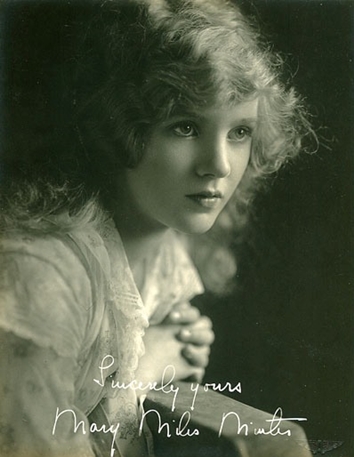

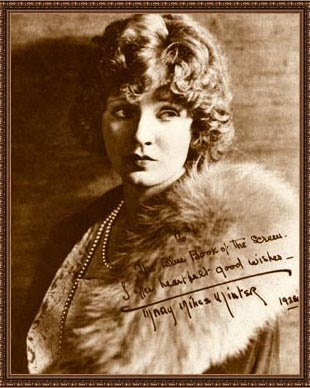

The other ruined career, of course, was Mary Miles Minter’s, and looking at her face in this picture that she (or, more likely, Mama Charlotte) signed for the 1923 edition of

Blue Book of the Screen, it’s impossible not to believe she knew the end was nigh. In the flurry of publicity after Taylor’s murder, all of

her publicity was bad. Love letters surfaced, some in a kind of schoolgirl code, that she had written to Taylor — they look girlishly innocuous to modern eyes, but in 1922 they were scandalous, and not in keeping with the sugar-and-spice-and-everything-nice image Charlotte and her studios had so carefully cultivated. Stories flew, and grew in the telling. In Taylor’s bedroom dresser, it was said, they found a pair of pink panties, embroidered with “MMM”; in a later iteration, the panties became a sheer nightgown. Whatever. The garment, the story went on, was passed around police headquarters for a while, for laughs, before vanishing altogether. (That is, if it ever existed at all. Minter herself denied it in a phone conversation with historian

Kevin Brownlow in the 1970s. She believed the panties/nightgown story was invented by journalist Adela Rogers St. John.)

Were Minter and Taylor — 15 and 45, respectively, when they met in 1917 — lovers? Only two people ever knew the answer to that one, and they both died without saying. Florence Vidor, for one, didn’t believe Minter was sexually active with Taylor or anyone else. When would she have the chance, with Charlotte never letting her out of her sight? Some friends of Taylor’s believed Minter was infatuated with the director, badgering him with pleas for his affection when he regarded her as no more than a dear little child; other acquaintances believed that, ahem, Taylor had no interest in women of any age — if you know what I mean.

Whatever the case, the damage was done. Even before the murder, the Hollywood establishment had begun to suspect that Mary Miles Minter’s time had all but passed; afterward, studios and the public at large regarded her almost as a has-been who wouldn’t go away. Reviews of her last picture, The Trail of the Lonesome Pine (released on April 15, 1923) were downright cruel. The New York Times: “The chubby Mary Miles Minter, who apparently does not often take as much exercise as in this production…” Variety wasn’t as unchivalrous as all that, but reviewer “Fred” dismissed her as “colorless.” Ten days later, Paramount bought out her contract for $350,000 and released her. She had just turned 21.

The murder of William Desmond Taylor was never officially solved, and it hung over Mary Miles Minter and her mother like a curse from beyond the grave. Eventually the two were driven to a public statement: the L.A. district attorney should put up or shut up; publish any evidence against them and charge them, or absolve them once and for all. The D.A.’s office replied that they had nothing, and absolved them. Over the years there’s been no shortage of theories. He was shot by a burglar. Or by Normand. Or one of her ex-lovers. Or a bootlegger to whom Taylor owed money. Or drug dealers, angered by his efforts to help Normand kick her habit and to have them driven out of town. Or a secretary who had disappeared after robbing Taylor and forging his signature to cash checks. Or, no kidding, the butler (one Henry Peavey) did it.

In 1967, 73-year-old director King Vidor, who had been a contemporary and acquaintance of Taylor’s, launched a personal investigation for a screenplay he hoped to write and direct. Many Hollywood old-timers were still alive then, and nearly all of them had their own take on the mystery. His efforts took him far and wide, visiting friends and former colleagues — including Mary Miles Minter herself. She was now living quietly in Santa Monica and answering only to Mrs. Brandon O’Hildebrandt, the name of the man she married in 1957, after Charlotte Shelby finally died. Her husband had died in 1965, leaving little Juliet Reilly a final name to fold herself into.

Or perhaps there was one more. Vidor was appalled to find an obese, demented wreck of the beauty he had known, looking far older than her 65 years and clearly mentally unstable. She said she was writing a lot these days, poetry of her own. When Vidor glanced at the stack of poems she had, he noticed they were all signed “by Charlotte Shelby.” As they talked, Mary wafted her way through a disjointed, wandering monologue, often ignoring or only half-answering Vidor’s questions. At length, she mewled, “My mother killed everything I ever loved,” but the director couldn’t tell if she was being momentarily lucid or merely surrendering to the confusion of dim and distant imaginings.

Vidor never made that movie, or any other feature, though there was an unrelated documentary short in 1980.

Solomon and Sheba in 1959 proved to be his final outing as a director. The fruits of his investigation were locked away in a strongbox in his garage, where they were discovered after Vidor’s death by his biographer Sidney D. Kirkpatrick. Kirkpatrick published the material in 1986, along with Vidor’s conclusions about the crime, as

A Cast of Killers. Since then another book has examined the Taylor murder in depth; this was

Tinseltown: Murder, Morphine and Madness at the Dawn of Hollywood by William J. Mann. Mann and Kirkpatrick — or rather, Mann and Vidor — reached quite different conclusions as to who killed William Desmond Taylor, and why, and I won’t reveal either one. Both books are good reads, and I wouldn’t care to spoil them. Besides, any would-be solution to the crime at this distance has to be based on circumstantial evidence, and circumstances can always change.

Juliet Reilly/Miles/Shelby/Mary Miles Minter/Mrs. Brandon O’Hildebrandt outlived King Vidor by nearly two years. Mentally fragile as she may have been, she was reasonably well-fixed thanks to real estate investments during the glory days. But her Santa Monica neighborhood grew perilous, and she was robbed more than once. During one robbery in 1981 she was bound, gagged, beaten and left for dead; she survived, and an ex-servant was charged with the crime. She died on August 4, 1984, age 82; any thoughts she had after that 1967 visit from King Vidor she most likely took with her. Mary Miles Minter has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 1724 Vine St., a little over five miles from the spot where William Desmond Taylor died.

POSTSCRIPT: In preparing this post, I went looking for a copy of A Cast of Killers, my first one having slipped out of my hands some twenty years ago. I found a copy at a used-book store, and snapped it up. When I got it home, I learned to my surprise that I had bought an autographed copy. On the title page, above his signature, Sidney D. Kirkpatrick had cautioned a previous owner: “Don’t let this story haunt you. It’s only Hollywood.”

And so did Charlotte. Somebody made up a nursery rhyme:

And so did Charlotte. Somebody made up a nursery rhyme:

He may have had other effects on her as well, and that possibility came to light only after the evening of Wednesday, February 1, 1922. On that night, sometime after 7:45 p.m., in the living room of this bungalow at 404-B Alvarado Street in Los Angeles, somebody stood behind William Desmond Taylor and shot him dead with a .38-caliber Smith & Wesson revolver.

He may have had other effects on her as well, and that possibility came to light only after the evening of Wednesday, February 1, 1922. On that night, sometime after 7:45 p.m., in the living room of this bungalow at 404-B Alvarado Street in Los Angeles, somebody stood behind William Desmond Taylor and shot him dead with a .38-caliber Smith & Wesson revolver.

Thanks for asking, Anon, and thanks for stopping by; hope you'll return often. Altogether, including research time, I worked about a week on this post.

Good Afternoon

This post was interesting, how long did it take you to write?

Yes, Lee, I've got plenty of names to work with. Unfortunately, these stars' presence in the deck is based on their popularity in pictures made between, say, 1911 and 1918 — approximately 95 percent of which are now lost forever, with maybe another three or four percent squirreled away in climate-controlled archives and (for commercial purposes) not worth issuing on video. So I'm left to comb through the archives of Variety and the New York Times for reviews, seeking some sense of the careers they had.

Going through a whole deck of cards should give you lots of material, if you ever get stuck for a posting!