This post is Cinedrome’s contribution to the Classic Movie Blog Association‘s first blogathon of 2013, Fabulous Films of the 1940s. (Now there’s a topic; CMBA could probably do five such ‘thons, with all members taking a different title, and never exhaust the possibilities!) Go here for a complete list of entries; you’ll find my colleagues holding forth on a mouthwatering array of movies legendary and obscure, long-remembered and half-forgotten.

Before I get into my own contribution to the blogathon, here’s a bonus: I can’t make it an official entry because I’ve already posted on this picture before. But if we’re talking about Fabulous Films of the 1940s, I can’t forgo mentioning one of my absolute favorites, Henry Hathaway’s Down to the Sea in Ships (1949). As I said in my post (which you can reach at the link), I simply don’t understand why this one isn’t one of the best-loved movies of all time; sooner or later (and if I have anything to say about it), I’m sure it will be. (UPDATE 2/18/13: Reader David Rayner of Stoke-on-Trent, England, whose admiration equals my own, has written to tell me that Down to the Sea has been released on Region 1 DVD in the US and is available here from Amazon. Don’t miss it!)

But now, getting back to the blogathon at hand — drumroll, please — here’s another one of my particular favorites from that embarrassment-of-riches decade…

* * *

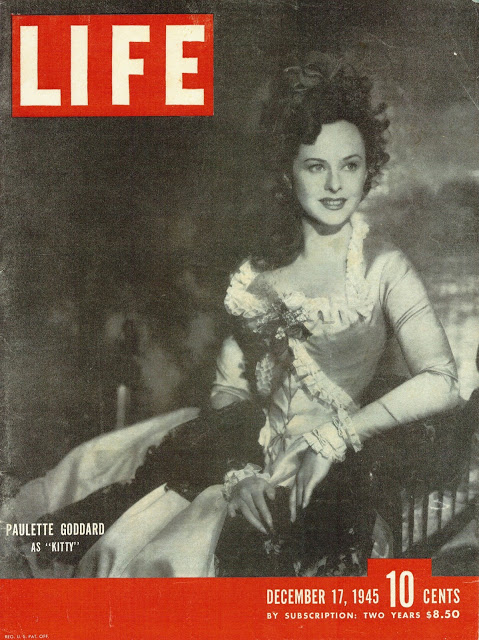

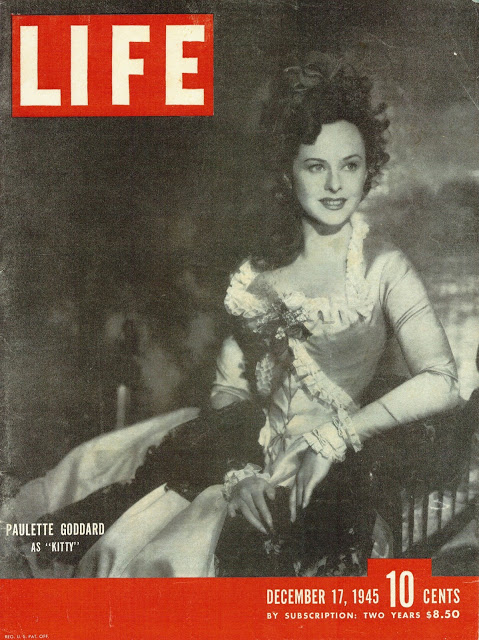

Paulette Goddard is one of the great also-rans of movie history. As she never tired of saying, she was the front-runner for the role of Scarlett O’Hara in Gone With the Wind — that is, until some pert little nobody from England came along. In an interview late in life, Goddard told how she had been finally offered the role and, understandably excited, decided to throw a party to celebrate. Selznick came, she said, and so did the English actor Laurence Olivier, in town shooting Wuthering Heights for Sam Goldwyn. Olivier (again, according to Paulette) brought along his girlfriend Vivien Leigh, Selznick took one look at her, and that was that.

The story is nonsense, of course. Goddard never had Scarlett nailed down, certainly not enough to throw a party over it. David Selznick’s first sight of Leigh is well-documented, and it wasn’t at Paulette’s house. Just about everybody knows that story, so I needn’t go into it here; suffice it to say the near miss on Gone With the Wind haunted Paulette Goddard for the rest of her life — through her 1940s peak at Paramount (when she never quite made it into the top rank of Hollywood stars), and especially through the long years before her death at 79 in 1990, years during which GWTW‘s fame grew even as her own dwindled.

There’s another sort-of connection with Gone With the Wind in Goddard’s career. It’s a bit of a stretch, I admit, but here goes: As you probably know, during the second half of the 1930s, Scarlett O’Hara was the most coveted role in Hollywood, and the novel’s millions of fans waited breathlessly for the movie David Selznick would make of it. Warner Bros. decided to cash in on the moss-magnolias-and-the-old-plantation fever by dusting off a 1933 Broadway flop by playwright Owen Davis called Jezebel, which also happened to be about a flirtatious and headstrong southern belle. Warners worked it up as a vehicle for Bette Davis and triumphantly swept it to the screen a year ahead of Gone With the Wind.

Fast-forward a few years to 1944. Another novel has set the hearts of America’s female readers a-flutter and got every actress in Hollywood rubbing her hands. The book is Forever Amber by 24-year-old Kathleen Winsor, about an ambitious village girl’s sexual exploits during the Restoration of Charles II of England, up to and including a liaison with the king himself. (Like Gone With the Wind, Forever Amber sparked a vogue for naming newborn girls after its heroine that endures to this day.) When this racy, titillating book by an unknown housewife sold 100,000 copies the first week (on its way to 3 million), Darryl Zanuck at 20th Century Fox wasted no time nailing down the movie rights. Undaunted, the boys at Paramount decided to steal a march on Zanuck the way Warners had on Selznick, and the beneficiary of their ploy was Paulette Goddard.

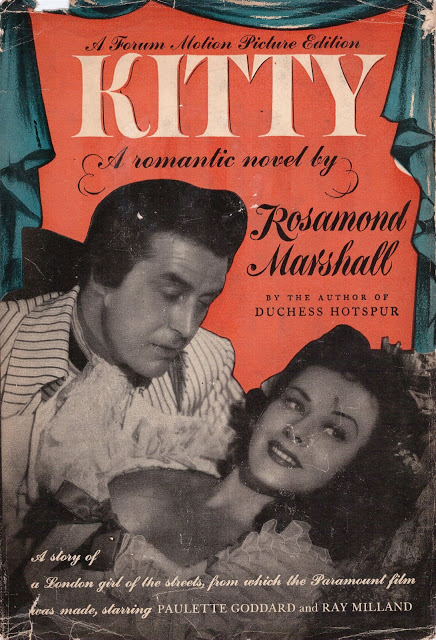

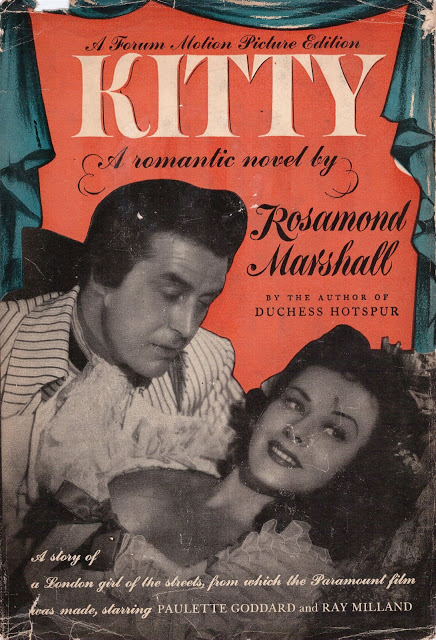

The book they chose was Kitty by Rosamond Marshall, which had been published the year before Amber, but without gaining anywhere near the same amount of sales or notoriety.

Born in 1902, Rosamond Marshall wrote some 16 novels altogether between her first, None But the Brave: A Story of Holland in 1942 and her last, The Bixby Girls, published in 1957, the year she died. Her books sold pretty well during her lifetime — especially in paperback reprints with semi-lurid covers and titles like Duchess Hotspur, Rogue Cavalier and The General’s Wench — but only two of them ever made it to the screen: The Bixby Girls (filmed in 1960 as All the Fine Young Cannibals with Natalie Wood and Robert Wagner) and Kitty.

Actually, though, not quite all of Kitty did make it to the screen. Marshall’s novel was what we now call a bodice-ripper, the tale of a 14-year-old London prostitute blithely sleeping her way up the social ladder during the days of King George III. As the story opens, Kitty — she doesn’t have a last name, or at least doesn’t know it — lives with and works for Old Meg in the wretched slums of Houndsditch. Old Meg sold Kitty’s virginity when the girl was only nine, and now Kitty spends her days thieving and her nights whoring, turning her loot and her earnings over to Old Meg in return for squalid shelter and crumbs of food.

One day Kitty indulges a common ploy: stealing the shoes of a gentleman as he’s being carried piggyback on his footman across a muddy street. When she’s caught and brought back to the man’s doorstep, he finds her face interesting and invites her in. He’s the painter Thomas Gainsborough, and he wants Kitty to pose for him. Once he’s had her washed and decently clothed he’s surprised to see that she’s not a child but a rather attractive young woman; she in turn is overawed by his studio, especially one portrait, which she impulsively dubs “Blueboy”.

Kitty also catches the eye of a visitor to Gainsborough’s studio, Sir Hugh Marcy. Sir Hugh is an impecunious ne’er-do-well, impoverished but charming. In time, through the picture Gainsborough eventually paints of her — “Portrait of an Anonymous Lady” — Kitty becomes the talk of London society. During the same time, Sir Hugh and his gin-sodden aunt Lady Susan take her under their threadbare wings, passing her off as Miss Kitty Gordon, the orphaned child of a dear friend. Day after day, they subject her to a crash course in proper speech and manners — while at night, Sir Hugh schools her in the unsuspected pleasures of orgasmic sex.

As years pass, Kitty blooms under their tutelage and her prospects improve. She marries a wealthy shipping merchant, bringing a welcome dowry to Sir Hugh and Lady Susan — although Lady Susan soon succeeds in drinking herself to death. Not long after, Kitty’s husband dies and Hugh arranges a second marriage to the aged Duke of Malminster. Kitty thus becomes a duchess, and she soon gives the duke an heir. The old boy never suspects that “his” son is really Sir Hugh’s; Kitty’s affair with him has continued throughout both her marriages.

That’s as much of the novel’s plot as we need go into here, because that (aside from the endless rounds of sex with Sir Hugh) is what remains in the movie Paramount released on October 16, 1945. Between publication and premiere, however, Rosamond Marshall’s story had to undergo a major overhaul at the hands of writers Karl Tunberg and Darrell Ware and director Mitchell Leisen.

Darrell Ware had been a prolific journeyman since 1936, turning out an array of dramas (A Yank in the R.A.F.), comedies (Charlie McCarthy, Detective) and musicals (Down Argentine Way, Orchestra Wives, My Gal Sal), none of which were particularly praised for their writing. Karl Tunberg’s career lasted longer, and he at least has the distinction of receiving sole screenplay credit for the 1959 Ben-Hur; his script was heavily doctored by Gore Vidal, Christopher Fry and others, and was conspicuous for being the only Oscar nomination that Ben-Hur didn’t win. Still, in Kitty, both Tunberg and Ware rose to the occasion with what was easily the best screenplay of their otherwise rather undistinguished careers. (Both men received associate producer credit on the picture — although their producing duties may not have amounted to much, at least not in Ware’s case: he died at age 37 in May 1944, nearly a year-and-a-half before Kitty‘s premiere.)

Their task with the novel’s plot was daunting. To begin with, of course, the idea of a prostitute as a heroine, let alone a 14-year-old one, was obviously out of the question. So Kitty was advanced to somewhere beyond the age of consent — and relieved of the need to have anything to consent to.

More important, Tunberg and Ware (with perhaps the collaboration of director Leisen) realized what Rosamond Marshall evidently did not: that next to Kitty herself, by far the book’s most interesting characters are the rakish cad Sir Hugh Marcy and the alcoholically haughty Lady Susan. In the novel, Lady Susan is dead halfway through; Sir Hugh disappears from Kitty’s life with far too many pages left to read, while Kitty rather unconvincingly transfers her affections to the now-adult subject of Gainsborough’s “Blueboy”. In the screenplay, both Sir Hugh and Lady Susan are kept around, to far more satisfying effect.

By the way, there’s a curious side note to this business of the painting: In reality the subject of Gainsborough’s famous portrait is not known for certain, but is believed to be one Jonathan Buttall, son of a wealthy London hardware merchant. In Marshall’s novel, this is the name of Kitty’s hot-tempered first husband, while the Blue Boy (a more accurate rendering of the portrait’s title) is named Brett Harwood, a cousin of Buttall’s. In the movie, all this was changed. The importance of the painting in Kitty’s life is downplayed, and Brett Harwood becomes a rival to Sir Hugh for Kitty’s heart. Meanwhile, her first husband is renamed Jonathan Selby — no doubt to avoid offense to any living descendants of the real J. Buttall.

But I digress.

Ware and Tunberg’s solution to Kitty‘s story problems — and its glaring conflicts with the Production Code — was elegantly inspired: They expanded and emphasized the scenes of Sir Hugh and Lady Susan schooling Kitty in ladylike comportment, thus changing Kitty‘s plot from the meteoric rise of an adolescent whore into an 18th century adaptation of Shaw’s Pygmalion, with Kitty (Paulette Goddard) as Eliza Doolittle, Sir Hugh Marcy (Ray Milland) as Henry Higgins, Thomas Gainsborough (Cecil Kellaway) as Col. Pickering, and Brett Harwood (Patric Knowles) as the sweetly besotted Freddie Eynsford-Hill. Shaw’s Mrs. Higgins, of course, became Lady Susan, and the role was entrusted to that grand dowager dragon of the British and Broadway stages, Constance Collier.

Bernard Shaw’s reaction to all this is unrecorded. I like to think the old boy would have been amused, but he may never have even seen the picture — and he almost certainly never read Marshall’s novel.

In addition to the “associate producers” credit for Darrell Ware and Karl Tunberg, Kitty is also billed as “A Mitchell Leisen Production”. In the mid-’40s Leisen was Paramount’s reigning arbiter of elegance, having begun his career as a set and costume designer for Cecil B. DeMille, the only Paramount director who outranked him in prestige. Leisen (it’s pronounced “Leeson”, by the way) has taken a beating from auteurists in recent decades. I suspect this is mainly because those two auteur darlings Billy Wilder and Preston Sturges both claimed to have turned director out of dissatisfaction with Leisen’s treatment of their scripts. But an unbiased look at the pictures Leisen made of Sturges’s screenplays for Easy Living (1937) and Remember the Night (’40), or Wilder’s (and Charles Brackett’s) for Midnight (’39) and Hold Back the Dawn (’41), makes them sound like a couple of whining prima donnas. Don’t get me wrong, I’m glad and grateful that Billy Wilder and Preston Sturges moved into directing their own stuff; but they had no grounds whatever to complain about Mitch Leisen.

David Chierichetti’s 1995 book

Mitchell Leisen: Hollywood Director does much to correct this injustice to Leisen, but its information on

Kitty is sketchy and unreliable. Chierichetti calls it the story of “a filthy cockney street waif of Restoration Era England”; in fact it takes place in Georgian England a full 125 years after the Restoration in 1660. Leisen himself, interviewed, says: “I spent two years researching Gainsborough and the way he painted. We determined that the picture took place in 1659, and there’s nothing in the picture that was painted by him after that year.”

Au contraire, Gainsborough wasn’t even born until 1727, and this frame from the picture states explicitly the year the story opens. Clearly, Leisen (who died in 1972) had not seen the picture recently when he discussed it with Chierichetti, nor had Chierichetti when he wrote about it. Leisen’s claim of spending two years in research is also plainly implausible:

Kitty was ready for release by the end of 1944 but was held up a full year by Paramount’s backlog of product; two years of research would have had Leisen beginning in 1942, a year before Rosamond Marshall’s novel was published. Altogether, these facts cast doubt on much of the information in the seven pages Chierichetti devotes to

Kitty.

But there is one point on which Chierichetti is absolutely right: Kitty “was precisely the kind of picture Leisen could do better than anybody else, and its mixture of mannered comedy and gutsy drama suited him perfectly”. The picture is a sumptuous feast for the eye, evoking 18th century London’s riot of teeming streets and Rococo decor as sharply as a series of engravings by William Hogarth. It’s a pity the picture couldn’t have been made in Technicolor — thus evoking Gainsborough rather than Hogarth — but Paramount was notoriously frugal on that score; among the major studios, even cheapskate Universal was more generous in their use of color. But even as it stands, Kitty richly deserved its Oscar nomination for art direction — for Hans Dreier and Walter Tyler; the production design was by Raoul Pene Du Bois. (Kitty lost; the award went to Anna and the King of Siam.)

Over and above its gorgeous look and elegent style, and entirely in keeping with it, Kitty gave Paulette Goddard the opportunity to deliver the performance of her career, and she came through with a performance nearly as good as Wendy Hiller’s in 1938’s Pygmalion (and considerably better than Audrey Hepburn’s in My Fair Lady). Always a conscientious actress rather than an inspired one, Goddard worked hard on her cockney accent. According to Chierichetti, Leisen credited Phyllis Loughton and Connie Emerald (mother of Ida Lupino) for this, adding that for Goddard’s diction as the new-and-improved Kitty, “we moved Connie Emerald out and Constance Collier in”, and the old girl coached Goddard/Kitty as much off screen as Lady Susan did on. There’s not a false note in Goddard’s performance, nor in any of the rest of the cast, which was surely one of the largest and best either she or Leisen ever worked with: Milland (against-all-odds charming as Sir Hugh, a more unsympathetic rotter than Henry Higgins ever was), Collier, Knowles, Kellaway, Dennis Hoey (as Kitty’s first husband), Reginald Owen (as her second), Sara Allgood (Old Meg) and the ever-popular Eric Blore as Sir Hugh and Lady Susan’s querulous manservant Dobson. (Blore has one of the picture’s best lines, which I hereby spoil for you: On Kitty’s first night in Sir Hugh’s household, Dobson hands her a tea tray and orders her to take it up to Lady Susan. Kitty: “‘Ow will I find ‘er?” Dobson: “Drunk, as usual!”)

Kitty is another of those pre-1950 Paramounts now owned by Universal. Like others I’ve written about before (MissMiss Tatlock’s Millions, Alias Nick Beal, Night Has a Thousand Eyes), it was often available in TV syndication during the 1960s and ’70s. Unlike them, however, Kitty hasn’t entirely vanished into the Universal vault. It’s turned up recently on Turner Classic Movies thanks to TCM’s agreement with Universal, so it’s out there somewhere for you to find, and to savor Leisen, Goddard, Milland et al. all at their best. There’s no “official” DVD yet — only ones of varying quality available here from Amazon and here from Loving the Classics. A full-scale DVD transfer, doing justice to those Oscar-nominated sets and Daniel L. Fapp’s cinematography, is long overdue. We can only wait, and hope, for Universal to come through.

UPDATE 2/14/18: Universal has come through. Kitty is now available in a very nice DVD transfer from the Universal Vault series (Universal’s answer to the Warner Archive). It’s bare-bones, of course, like all such issues from Warner, Universal and Fox, with no extras (if Universal is interested in adding a commentary, I’m happy to volunteer), but well worth having. You can get it here from Amazon.

Great post!

I really enjoyed this film and I'm glad you selected it to write about.

Wow! What background material! You tell it well. I'd never heard of it before this, but I'm looking forward to watching KITTY.

Thanks.

Eve, I'm sure you're right about Sturges; I suspect the same is true of Wilder. I've never read any of Wilder's scripts, but I have read Sturges's for Remember the Night, and there were minor changes between that and the finished picture that were no doubt Leisen's work on the set. They in no way altered or diminished the text, but may have been just enough to ruffle the feathers of a control freak. Writers are a touchy bunch.

Jim, I thoroughly enjoyed learning what seems to be everything I ever wanted to know about "Kitty." So entertaining and informative! I had no idea, for I haven't seen the film. Well, I will find it now. You certainly covered a lot of ground here and none of it less than fascinating. Thank you for a great read and for alerting me to a film I've somehow managed to overlook. I did want to add somewhat on Preston Sturges' behalf that he seemed to be the type who liked being in charge of every aspect of everything. I suspect he could barely tolerate anyone else 'tampering' with his work. Leisen did a marvelous job on "Remember the Night," one of my favorites.