The 11-Oscar Mistake

The 50th Anniversary Ultimate Collector’s Edition of Ben-Hur is out. Mine arrived last week, number 13,192 of 125,000 — so be warned: If you want your own copy, you’ve got only 111,808 more chances to buy it. As 50th Anniversary Editions go, this one is a little tardy, by nearly 22 months; the picture premiered in New York (at the Loew’s State on Broadway) on November 18, 1959.

New York had a lot more daily newspapers in those days, and movie reviews were a lot more important, especially to a roadshow attraction like this that couldn’t count on a big ten-jillion-screen opening weekend to make most of its money. A picture like Ben-Hur had to have “legs”, and for that the New York critics were as important as they were to any first night on a Broadway stage. If the suits at MGM had been worried about the critics, they were breathing a lot easier by the afternoon of November 19. The chorus of praise was deafening: “a remarkably intelligent and engrossing human drama” (New York Times); “squirms with energy” (Tribune); “a classic peak” (Post); “stupendous” (Daily News); “extraordinary cinematic stature” (Journal-American); “massive splendor in overwhelming force roars from the screen” (World-Telegram).

If you agree with all these encomia, you might want to read no further, because I don’t agree and I never have. As far as I’m concerned, of all the lousy movies that have won the Oscar for best picture (a very crowded field), Ben-Hur may be the lousiest of the lot. (“Well, if you feel that way about it, why did you shell out 45 smackers for a deluxe boxed Blu-ray?” Good question; all I can say is, just as not every good movie is important, not every important movie is good.)

Let me remind you (if you’re old enough to remember) or tell you (if you’re not) how moviegoing has changed in 50 years. Forget home theaters, forget cable or satellite TV, forget Tivo or Internet streaming, forget even multiplexes. What they now call “platforming” wasn’t a rare distribution strategy in those days, it was how all movies were handled. A movie would open in the big cities first — New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, maybe San Francisco, Atlanta, Washington DC, St. Louis and a few others. Maybe in two or three theaters in the big cities, but probably in only one (and all theaters had only one screen). After its first run, the movie would filter down to smaller theaters in the big markets and bigger theaters in the smaller markets. If your hometown was small enough and far enough from a major market, you could have months of mounting anticipation before you had a chance to see the movie everybody you didn’t know was talking about.

And absolutely forget about waiting till a movie turned up on HBO or Netflix. You’d have one chance to see it; even then it might play only three or four days and be gone. If you couldn’t catch it those days, you could hope it would be held over or brought back. Maybe it would, maybe it wouldn’t. If not, you could watch for it at your local drive-in or theaters in a neighboring town, maybe in vain. That was moviegoing in the 1950s.

This dynamic was intensified in the case of roadshow attractions. I don’t mean just the Cinerama movies, which were a special case all to themselves. I mean movies like Oklahoma!, Around the World in 80 Days, The Ten Commandments, South Pacific; they might play a year or more in metropolitan areas before going into general release (“Now at popular prices!”). Where we lived in Northern California, the nearest big city was San Francisco; I had friends whose parents took them down there to see Oklahoma! and Around the World, but my family never went in for that; I just had to wait. (I didn’t see Oklahoma!, for example, until 1961, and only then because we moved to Sacramento in the summer of 1960.)

As it turned out, this milestone in the march of Western Art was only a movie after all. And to my bewildered surprise, as I sat there in the throng — the Alhambra held 2,500 and it was jam-packed to the last row of the balcony — I found a startling thought running unbidden through my head: “This movie…isn’t…very…good.”

The first stirrings of disappointment came during the pre-title sequence showing the birth of Jesus, with the Wise Men tromping up and plopping their gifts down. It looked as awkward to me as a Nativity Scene enacted by a Sunday School kindergarten…

They didn’t. By the time of the “great sea battle” — nearly an hour and a half later — I had about decided somebody was pulling a fast one. I was twelve years old and thinking, “How fake!” Maybe it was the huge screen, but these boats looked like bathtub toys. Howard Lydecker (though I didn’t know his name at the time) had done a better job on Sink the Bismarck!, and with probably one-tenth the money MGM spent on this.

I left the Alhambra Theatre that evening sadder, wiser, and four hours older, with a valuable lesson: Don’t believe everything you hear.

Seeing the picture again and again over the years brought into focus things that I hadn’t specifically noticed the first time, but that I could see had added to my general disappointment, like the solemn, leaden pace, with pregnant pauses between and during the speeches, each pause several weeks more pregnant than the last. Or the dull non-performance of Haya Harareet as Esther, Judah Ben-Hur’s love interest. Harareet had little screen presence and less chemistry with Charlton Heston (for contrast, see Heston and Sophia Loren in El Cid), and after Ben-Hur Harareet’s career went precisely nowhere. (For that matter, that’s where it went even during Ben-Hur.)

On a related side-note, we’ve all heard Gore Vidal’s story about how he saved the Ben-Hur script by writing in a homoerotic subtext between Heston’s Ben-Hur and Stephen Boyd’s Messala, a story Vidal continues to tell despite on-the-record denials from both Heston and director William Wyler before they died. Well, maybe it’s there and maybe it isn’t; by the time Vidal started talking about it, Stephen Boyd was no longer around to give his take on it. More obvious to me — now, I mean, not in 1960 — is the same subtext between Ben-Hur and the Roman soldier Quintus Arrius (Jack Hawkins) during the rowing drill in the galley; Arrius gazes intently through hooded eyes at the half-naked Judah as the hortator steps up the drumbeat and Judah strokes, strokes, strokes, faster and faster. Maybe Vidal wrote that too, and maybe Hawkins played it, I don’t know. My point is that all this talk about real or imagined homoerotic undercurrents in Ben-Hur is possible at least in part because plainly, there’s absolutely nothing going on between Charlton Heston and Haya Harareet.

But back to my train of thought. When I saw Ben-Hur in September 1960, I had already read and enjoyed the book, so I never for a minute believed that the movie had simply gone over my 12-year-old head. Here was a picture that, as I saw it, was mediocre at best, yet it had critics everywhere flying into transports of ecstasy. Even the reliably hypercritical Time Magazine said that the script “sometimes sing[s] with good rhetoric and quiet poetry.” (Really? Somebody quote me a line or two of that singing, quiet poetry. I dare you.)

To me it was a paradox, one I mulled over intermittently for years. Finally I came up with…I can’t really call it a theory, exactly; it’s more a hypothesis. No doubt it’s a gross over-simplification, but I think it’s worth trotting out and looking at.

And now this brings me to what I mean by the title of this post: “The 11-Oscar Mistake”. I don’t mean to say that giving Ben-Hur 11 Oscars was a mistake (although I think it was). What I mean is that there was a serendipitous mistake in the picture itself that wound up making it a huge hit and winning it 11 Oscars.

The mistake happened during shooting of the one sequence where Ben-Hur unquestionably delivers the goods: the chariot race. It’s 8 min. 38 sec. of pure visceral excitement, and to get the full pulse-pounding impact of it you really had to see it in a huge theater on an 80-foot screen with 2,499 other people who were just as edge-of-the-seat excited as you were. (When was the last time you saw any movie with thousands of strangers? I’ll bet it’s been a while.)

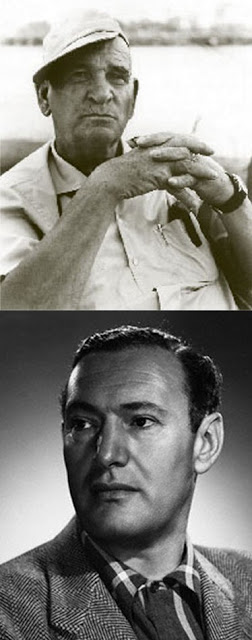

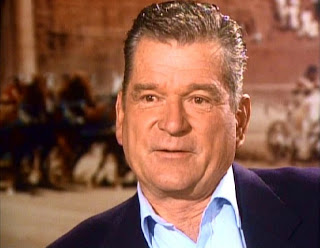

The chariot race was the work of second unit directors Enos Edward “Yakima” Canutt and Andrew Marton (finally assembled by editors John D. Dunning and Ralph E. Winters). Yakima Canutt is far and away the greatest and most famous stuntman who ever lived, with a career spanning 60 years from Foreman of Z Bar Ranch in 1915 to Breakheart Pass in 1975 (when he was 80). He all but invented the craft of movie stunt work, and he literally invented any number of safety devices to minimize the inherent dangers of the job. As either stunt performer, stunt coordinator, second unit director, producer or actor (sometimes wearing more than one hat on the same picture) he racked up nearly 500 titles in his filmography. (He also has the distinction of being the first man to go before the cameras in Gone With the Wind, doubling Clark Gable in the burning-of-Atlanta sequence.) For Ben-Hur Canutt selected and trained both the horses and drivers for the race.

Andrew Marton’s career was almost as long as Canutt’s (from 1927 to ’77), most often as director (King Solomon’s Mines [’50], The Longest Day, Crack in the World, Clarence the Cross-Eyed Lion) but also as second unit director on many major pictures (The Red Badge of Courage, A Farewell to Arms [’57], Cleopatra [’63], Catch-22, The Day of the Jackal). On Ben-Hur Marton was in charge of the crew behind the camera while Canutt handled the human and animal crews in front of it.

Joe worked long and carefully with his team before the shoot. He took the horses up and over the ramp one at a time, then in pairs harnessed together, then threes, then all four, then the four harnessed to an empty chariot, and finally all four, the chariot and Joe. At last everybody, human and equine, was comfortable with the stunt.

Here’s how the sequence was planned, shot by shot — each shot, obviously, filmed separately, even on different days, to be assembled later, rather than as one continuous action:

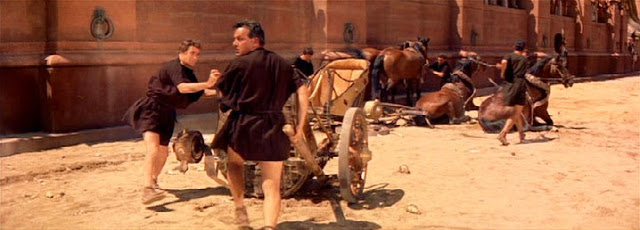

First a shot of slaves scurrying to clear the wreckage and horses of two chariots before the racers come round again.

Messala, knowing what’s just around the bend, crowds Ben-Hur’s chariot (with Heston at the reins) hard against the spina as they come around the turn.

Joe’s chariot hit the ramp. In this frame you can see that the horses are just leaping clear on the other side. (You can also clearly see, with the frame frozen, that it’s not Charlton Heston driving.)

An instant later the team is safely clear and galloping away, but Joe’s trouble is just beginning.

The chariot begins to descend and Joe goes into free fall, hanging for dear life onto the front rail.

The heavy chariot is still coming down and Joe is almost perfectly perpendicular.

Now his feet are over, putting him in a back-bend. He’s a heartbeat away from either being crushed by the half-ton chariot or having the meat ripped from his bones by the bolts studding the underside. (And hey, look over to the right; see that? Yep, it’s one of Andrew Marton’s cameras. I’ll bet even the editors never saw it. The camera is on screen for eight frames, one-third of a second — just long enough to notice if you look that way. But of course nobody ever has.)

It was in this nanosecond that Joe Canutt displayed the combination of quick thinking and athletic prowess that marks the difference between a great stuntman and a dead one. It beggars belief, but here’s what he did: just before his body toppled completely over, he let go his grip on the front rail of the chariot, dropped to a handstand on the tongue just behind the horses’ flying hooves, and pushed himself to the side and clear away. Now I’ve never done a handspring off the tongue of a chariot at a full gallop, but I’m guessing it’s not the kind of thing you can practice for; either you can do it when you have to or you can’t. Joe Canutt could do it.

He didn’t escape entirely uscathed, though. Something on the passing chariot clipped him on the chin, requiring four stitches. He was back at work after half an hour.

Joe Canutt, against all odds, was alive and well, but the shot itself was a dead loss, and after seeing his son go halfway to glory and back again, Yakima Canutt was in no mood to try it again. But according to Heston, at the screening of the dailies the normally detached William Wyler nearly choked when he saw the shot. “Jee-zuss!“ he cried. “We have to use that!”

Yakima Canutt balked. “Don’t see how y’ gonna do that. I promised Chuck he’d win this race. I don’t believe he can catch that team on foot.”

But Wyler knew just how to salvage the shot. Neither Yak nor Heston was crazy about the idea but they did it:

Tristan Bernard once said, “Audiences want to be surprised, but by something they expect.” Joe Canutt (by accident) and William Wyler (by design) created a moment that achieved the near-impossible: it made Judah Ben-Hur winning the chariot race — which everybody expected — a genuine surprise.

For all the New York Times’s puffing about engrossing human drama, or Time Magazine’s mooning over lines of quiet poetry, I say Ben-Hur (1959) really pretty much boils down to the chariot race — and the chariot race boils down to that somersault Joe Canutt took on a miscalculated stunt. Don’t get me wrong, the whole race is brilliantly staged, shot and edited, but that moment makes it an emotional as well as a visceral experience. At that point, the chariot race still has nearly three minutes to run, and the picture itself nearly 50. But that’s the emotional climax of the race, and of the whole movie.

I admit, this hypothesis is something I concocted about a movie I didn’t like very much, to try to understand why so many people did. As I said, it’s no doubt an over-simplification. And yet, and yet — I can never prove it, but I’ll always suspect that some of those 11 Oscars, maybe even best picture itself, would have gone home with somebody else if Joe Canutt had been a little more cautious as he pointed his team toward that ramp.

The Cannutts were full-goose-bozo crazy, but unlike so many patently insane people, they found a way to turn a profit on it.

The chariot race is certainly the dramatic high point of the film, and the bit that everyone talked about. Twas ever thus; in every production of the story, the most time was spent in getting the race right. IIRC, the stage production had live horses on stage, running on a treadmill. So like a real chariot race, theatergoers were presented with a very real chance of seeing someone reduced to hamburger and kindling right in front of them.

I do not think it's nearly as poor a film as you do, and people who sit down with a "Get to the effing monkey" (After the song by Tripod about Peter Jackson's King Kong) mindset miss out on one heck of a film.

One thing that a great deal of people don't grasp is that Ben Hur is not the star of the story; Jesus is, tho he appears on screen barely at all, and does not speak. The film is not about Judah's revenge, but his conversion. If it were about revenge, the chariot race would be at the end of the film, he'd be carried off the field by his friends, his family would appear from the crowd, Massala would fall in mud, and reprise the theme song and roll the credits. Instead we get another hour or so (it seems) of him seeing Christ again, finding his family, and becoming quite a different person by the film's end.

One of my favorite scenes is Boyd's last – he brings Judah to his bedside, just as he thinks he's won a moral victory, and says "Your family is alive, they've been alive all along, and I'm not telling you where they are.

If they were to do a remake today, there would be more than one company exec asking "Could we take out the religious subplot? It's only dragging the film down"

Jim, your BEN-HUR post "The 11-Oscar Mistake" was a fascinating read! I enjoyed your "The Emperor has no clothes" approach, as well as your scene-by-scene approach to Yakima and Joe Canutt's choreographing of the chariot race, the one scene that was unquestionably worth the price of roadshow admission prices! 🙂 Amazing how that one scene (and the drama surrounding how it came to be) really brought BEN-HUR to life. Your description of seeing BEN-HUR in a mammoth movie palace with a packed house brought me back to the days when I was a kid and going to a movie was truly an event — back when TV and TiVO weren't readily-available options! 🙂 And for the record, I'm a huge fan of Miklos Rosza's music. Great article, Jim!

Thanks, Eve; I'm glad you enjoyed going back in time with me to the lost, lamented Alhambra to see the still-with-us Ben-Hur. I tried to recreate the experience for those who may disagree with other parts of my post.

Jim, I didn't have the critical eye you had already developed when I was a child and first viewed "Ben-Hur" – I was swept up into it – though I don't remember anything about the experience other than that the theater was packed and that I had some sort of – spiritual? – dream later that night. However, when I saw the movie again years later on TV I was underwhelmed. I doubt that I've watched it all the way through since, so there isn't anything I can add or debate on the subject of its merit or Oscar-worthiness.

I enjoyed "accompanying you" to the theater and reliving your youthful viewing experience. And your shot-by-shot tale of Joe Canutt's chariot near-disaster is spellbinding. You present a very interesting and compelling take on why "Ben-Hur" may have been so popular and award-winning…

Kevin, we can agree to disagree about Ben-Hur (I much prefer the silent version), but we're of one mind on Dark Knight; don't get it and never have. (We may both be asking for trouble on that; Dark Knight has an emotional following that Ben-Hur can only envy.)

I agree too about the performance of the actor playing the Roman soldier when Ben-Hur's slave gang stops in Nazareth (I believe the man's name was Noel Sheldon). In fact, I'd venture to suggest that he gives one of the best performances in the picture.

Very interesting, Jim. I'm one of those that thinks "Ben-Hur" is one of the greatest movies ever made, and I find myself engrossed every minute of its almost four hour running time. Looking forward to watching the new Blu-Ray in my friend's home theater.

Being a huge Miklos Rozsa fan, and since I think this is his masterpiece, and one of the great symphonic achievements of the 20th century, maybe it goes down smoother for me than you.

After the chariot race, my favorite scene is the one in the desert when Christ gives Ben-Hur the water, to the consternation of the Roman centurion. It's a beautifully acted – and yes, scored -scene.

I do agree with you about the model ships and how much better the Lydeckers could have done it. Aren't the models in "Sink the Bismarck" just beautiful to look at?

For me the film deserved its 11 Oscars, but one. Hugh Griffith for Supporting Actor? No, I would have given it to George C. Scott for "Anatomy of a Murder." I don't get that award at all. Never have and never will.

I also don't mind Haya Hareet that much, but fortunately she's not in the movie that much. I do remember her in a Stewart Granger spy flick called "The Secret Partner" but can't remember if she made an impression there either.

Despite my disagreeing with you, I did enjoy your piece immensely. It's always interesting to read and hear conflicting opinions about favorite films.

I'm in the same position about "The Dark Knight" which for me may be the most overrated movie ever made. I don't begin to undestand the acclaim that movie received. I had that same sinking feeling watching that you did watching "Ben-Hur" all those years ago.