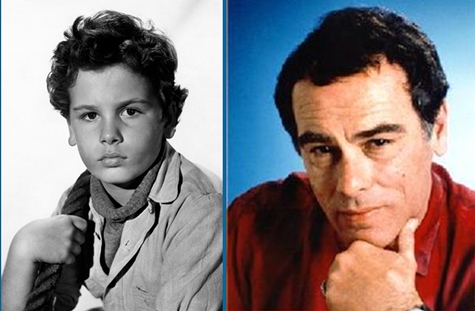

While preparing my post on the first day of this year’s Cinevent 52 in Columbus, Ohio, I learned of the passing of Dean Stockwell at his home in Ranchos de Taos, New Mexico on November 7 at the age of 85. Stockwell, boy and man, was one of the finest actors who ever faced a movie camera, yet he never quite received the recognition or accolades he deserved — no Oscar (“real” or honorary), no Presidential Medal of the Arts, no Kennedy Center Honors. All he ever managed was a couple of Golden Globes (which everybody knows are worthless); ensemble acting awards at Cannes for Compulsion in 1959 (shared with Bradford Dillman and Orson Welles) and Long Day’s Journey Into Night in 1962 (with Katharine Hepburn, Ralph Richardson and Jason Robards Jr.); and a star on that crummy Hollywood Walk of Fame. Nevertheless, he was one of our best, so steady, so reliable, and around so long that we could become lulled into believing he’d always be there.

While preparing my post on the first day of this year’s Cinevent 52 in Columbus, Ohio, I learned of the passing of Dean Stockwell at his home in Ranchos de Taos, New Mexico on November 7 at the age of 85. Stockwell, boy and man, was one of the finest actors who ever faced a movie camera, yet he never quite received the recognition or accolades he deserved — no Oscar (“real” or honorary), no Presidential Medal of the Arts, no Kennedy Center Honors. All he ever managed was a couple of Golden Globes (which everybody knows are worthless); ensemble acting awards at Cannes for Compulsion in 1959 (shared with Bradford Dillman and Orson Welles) and Long Day’s Journey Into Night in 1962 (with Katharine Hepburn, Ralph Richardson and Jason Robards Jr.); and a star on that crummy Hollywood Walk of Fame. Nevertheless, he was one of our best, so steady, so reliable, and around so long that we could become lulled into believing he’d always be there.

I can think of no more fitting tribute to the late Mr. Stockwell than to reprint my 2010 post on the picture in which the 12-year-old Dean gave the finest performance of his 70-year career: Henry Hathaway’s Down to the Sea in Ships (1949).

Farewell, Dean Stockwell, and thanks for the memories.

* * *

In 1949 Henry Hathaway made one of the best movies of his long career. In it, his three stars, Richard Widmark, Lionel Barrymore and Dean Stockwell (and for that matter, most of the supporting cast) each gave one of his own best performances. Down to the Sea in Ships is in fact one of the finest movies ever to come out of the Hollywood studio system, and almost nobody has ever heard of it.

In 1949 Henry Hathaway made one of the best movies of his long career. In it, his three stars, Richard Widmark, Lionel Barrymore and Dean Stockwell (and for that matter, most of the supporting cast) each gave one of his own best performances. Down to the Sea in Ships is in fact one of the finest movies ever to come out of the Hollywood studio system, and almost nobody has ever heard of it.

I know I run the risk of overselling the product here, but I simply don’t understand why Down to the Sea in Ships isn’t one of the best-loved movies of all time. When the talk turns to the great seafaring stories of the screen — Treasure Island, Mutiny on the Bounty, Captains Courageous, Moby Dick et al. — it’s a mystery to me why Down to the Sea in Ships never comes up. If there are such things as flawless movies, and there surely are, Henry Hathaway’s Down to the Sea in Ships is one of them.

I say “Henry Hathaway’s” to distinguish this picture from the other Down to the Sea in Ships, from 1922. That one made a star out of Clara Bow, and curiously enough, it’s available on home video — no doubt because it’s in the public domain, while Hathaway’s picture is still under copyright and quarantined in the 20th Century Fox vault. In the 1960s and ’70s it was the other way around: Down to the Sea in Ships (1922) was gone and long forgotten, but if your local TV station had a decent film library and you were willing to stay up till two or three in the morning, you could count on seeing Down to the Sea in Ships (1949) two or three times a year.

Before we leave the subject of Clara Bow’s breakout vehicle for good, let’s get one point clear: Wikipedia says that the 1922 picture “was remade by Twentieth Century Fox in 1949,” but — well, that’s Wikipedia for you. (Whoever wrote the article didn’t even know that it’s “20th Century Fox,” not “Twentieth.”) In fact, there is no connection whatsoever between the two pictures — other than the fact that they both deal with whaling ships out of New Bedford, Mass., and they both take their title from Psalm 107:23 (“They that go down to the sea in ships, that do business in great waters…”). These aren’t two versions of the same story, they’re two different movies with the same title; henceforth, when I use the title, I’ll be talking about only one of them.

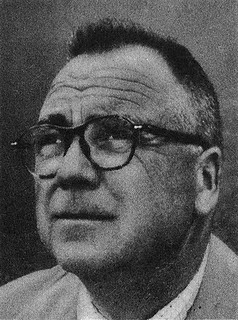

After the war, Zanuck reactivated the project and handed it over to producer Louis D. (“Buddy”) Lighton and director Hathaway. Both men were working for Fox now, but they had been paired before in the 1930s at Paramount: Lighton had produced the Shirley Temple vehicle Now and Forever, The Lives of a Bengal Lancer, and Peter Ibbetson, all of which Hathaway directed. The first draft of the script was by Sy Bartlett — that’s him at right — born Sacha Baraniev in Russia (now Ukraine) in 1900 but raised in America from the age of four. Originally a newspaper reporter, he became a screenwriter for various studios in the ’30s, but he was noted more for hobnobbing in Hollywood society, hosting Sunday barbecues, and the occasional gossip-column appearance. He served with the U.S. Army Air Corps during World War II, then returned to Hollywood and a job at Fox. At the time that he took his first cut at Down to the Sea in Ships, Bartlett’s most memorable work was still ahead of him: he later turned his wartime experience into the novel and screenplay Twelve O’Clock High (1949) for director Henry King and star Gregory Peck.

After the war, Zanuck reactivated the project and handed it over to producer Louis D. (“Buddy”) Lighton and director Hathaway. Both men were working for Fox now, but they had been paired before in the 1930s at Paramount: Lighton had produced the Shirley Temple vehicle Now and Forever, The Lives of a Bengal Lancer, and Peter Ibbetson, all of which Hathaway directed. The first draft of the script was by Sy Bartlett — that’s him at right — born Sacha Baraniev in Russia (now Ukraine) in 1900 but raised in America from the age of four. Originally a newspaper reporter, he became a screenwriter for various studios in the ’30s, but he was noted more for hobnobbing in Hollywood society, hosting Sunday barbecues, and the occasional gossip-column appearance. He served with the U.S. Army Air Corps during World War II, then returned to Hollywood and a job at Fox. At the time that he took his first cut at Down to the Sea in Ships, Bartlett’s most memorable work was still ahead of him: he later turned his wartime experience into the novel and screenplay Twelve O’Clock High (1949) for director Henry King and star Gregory Peck.

Without access to what records might be in the 20th Century Fox archives, it’s impossible for me to say exactly how credit for Down to the Sea‘s script should shake out — which is a pity, because the script is a truly masterful piece of work; if the picture ever gets the kind of attention it has deserved for over 60 years, maybe someone will shed some light on the subject. The writing credit on screen reads “Screen Play by John Lee Mahin and Sy Bartlett; From a Story by Sy Bartlett,” which matches the general drift of the two writers’ careers: story was Bartlett’s long suit, dialogue Mahin’s. Making an educated guess, I’d say Bartlett was responsible for Down to the Sea‘s distinctive blend of rousing adventure and psychological acuity, Mahin for the unerring cadence and vocabulary of the speech of 19th century New England whalermen. Or it may have been more complicated than that; Mahin gets top billing on screen, which suggests that his rewrite probably amounted to more than just touching up the dialogue.

Down to the Sea in Ships opens in New Bedford in the summer of 1887. The whaling ship Pride of New Bedford returns from a four-year voyage under the command of Capt. Bering Joy (Lionel Barrymore), the best whaler on the New England coast. He’s just about the oldest, too, though he shows no signs of being ready to retire from the sea. The reason for that is his 11-year-old grandson Jed (Dean Stockwell), the youngest in a line of the whaling Joy family that extends back “mighty nigh two hundred years.” Capt. Joy, though still on crutches from an injury that kept him bunk-ridden for much of the voyage, is unwilling to retire, at least until Jed is thoroughly brought up in the ways of the sea and can continue the family tradition. Jed himself is (if you’ll pardon the expression) entirely on board with this; he loves the seafaring life, the only life he’s ever known. He’s spent the last four years — nearly half his life — as his grandfather’s cabin boy, and is now eager to ship out again as an apprentice member of the fo’c’sle crew.

Down to the Sea in Ships opens in New Bedford in the summer of 1887. The whaling ship Pride of New Bedford returns from a four-year voyage under the command of Capt. Bering Joy (Lionel Barrymore), the best whaler on the New England coast. He’s just about the oldest, too, though he shows no signs of being ready to retire from the sea. The reason for that is his 11-year-old grandson Jed (Dean Stockwell), the youngest in a line of the whaling Joy family that extends back “mighty nigh two hundred years.” Capt. Joy, though still on crutches from an injury that kept him bunk-ridden for much of the voyage, is unwilling to retire, at least until Jed is thoroughly brought up in the ways of the sea and can continue the family tradition. Jed himself is (if you’ll pardon the expression) entirely on board with this; he loves the seafaring life, the only life he’s ever known. He’s spent the last four years — nearly half his life — as his grandfather’s cabin boy, and is now eager to ship out again as an apprentice member of the fo’c’sle crew.Unfortunately, the decision may be taken out of both their hands. The whaling firm’s insurance company refuses to cover Capt. Joy; moreover, Massachusetts law will not allow Jed to return to sea unless he can pass an exam covering the four years of schooling he missed while he was away. Fortunately, a sympathetic school superintendent (Gene Lockhart, in a warmhearted cameo) fudges Jed’s test results rather than disappoint the captain.

For his part, Dan Lunceford doesn’t care much for the look of Capt. Joy, nor for his sneering at Lunceford’s “book-learnin'” and his college degree in marine biology; only a sweetening of his percentage of the voyage’s profits persuades the younger man to ship out with Capt. Joy after all.

Once the Pride of New Bedford is out to sea, Capt. Joy plays his trump card. He tells Lunceford that he sees “the hand of Providence” in Lunceford’s presence on board. Jed was allowed to ship out, he says, only on the condition that his studies be continued, and Capt. Joy is hereby assigning Lunceford, in addition to his regular duties as first mate, to be Jed’s tutor during his off-duty hours. In this way, the crafty old mariner intends to kill two birds with one stone: he’ll see to Jed’s education, and he’ll keep Lunceford too busy to undermine his authority.

Lunceford has no choice but to accept the assignment, but he does so with ill grace. Resentful at what he regards as essentially a babysitting chore, he is impatient, sarcastic and dismissive. Resentful in turn, Jed is obstreperous and uncooperative. Lunceford decides Jed is just as ornery and pigheaded as his grandfather, and he give up the lessons as a waste of his time.

Stung, Jed applies himself and in time surprises Lunceford with answers to all the questions that had stumped him before. Lunceford suddenly approaches his duties as tutor in earnest, tailoring lessons more carefully to Jed’s quick and lively but unsophisticated intelligence. As the friendship grows between Jed and Lunceford, Capt. Joy begins — rightly or wrongly — to fear that his grandson’s respect and affection are drifting away from himself and attaching themselves to Lunceford; he responds to the unexpected competition by looking more carefully at Lunceford’s ideas, which he had formerly dismissed as not worth his attention. All this happens even as the Pride of New Bedford roams the waters of the South Atlantic, stalking and taking whales.

That’s about as much of the plot as I care to go into here; better that you should discover the rest for yourself. Down to the Sea in Ships isn’t available on home video*, but it does surface (pun intended) from time to time on the Fox Movie Channel, and it’s worth seeking out to discover how the three-generation, three-way relationship of Capt. Joy, Jed and Dan Lunceford plays itself out against the background of a perilous voyage contending with the forces of nature and the leviathans of the deep. Each of the three discovers qualities of strength and character in the others that he either never suspected or did not properly value at first. Each brings out the best in the other two, and allows the other two to bring out the best in him.

All this, mind you, while the movie does not skimp on action and high adventure. There are scenes of whale chases and boats lost at sea, suspenseful and beautifully shot (Joe MacDonald) and edited (Dorothy Spencer), with excellent special effects (Fred Sersen and Ray Kellogg). Capping it all is a climactic sequence in which the Pride of New Bedford runs aground on an iceberg in the fog near the horn of South America…

All this, mind you, while the movie does not skimp on action and high adventure. There are scenes of whale chases and boats lost at sea, suspenseful and beautifully shot (Joe MacDonald) and edited (Dorothy Spencer), with excellent special effects (Fred Sersen and Ray Kellogg). Capping it all is a climactic sequence in which the Pride of New Bedford runs aground on an iceberg in the fog near the horn of South America…

…with the crew struggling desperately to free themselves and repair the damage before the sea pounds their ship to splinters against the unforgiving ice. Not to mince words, it’s an absolutely brilliant action/suspense set piece. Amazingly enough, it was shot entirely in a soundstage tank on the Fox lot, but it’s spectacularly convincing and harrowing for all that.

Down to the Sea in Ships was Lionel Barrymore’s last starring role, on loan from MGM. Once, when introducing Barrymore on a 1939 radio broadcast, Orson Welles referred to him as “the most beloved actor of our time.” It was probably an exaggeration, but not by much; Barrymore’s stock in trade was playing cantankerous old codgers with hearts of gold. Ironic, then, that the only role for which he’s widely remembered today is Old Man Potter in It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), one of the most thoroughly heartless characters in the history of movies. In his own day Barrymore was more closely identified with wise old Dr. Gillespie in MGM’s Dr. Kildare series, and with his annual holiday performances as Ebenezer Scrooge on radio. In fact, Barrymore had been slated to play Scrooge in MGM’s A Christmas Carol (1938) until he broke his hip in an auto accident. That injury landed him in a wheelchair, then advancing arthritis kept him there for the rest of his career — until Down to the Sea in Ships.

Down to the Sea in Ships was Lionel Barrymore’s last starring role, on loan from MGM. Once, when introducing Barrymore on a 1939 radio broadcast, Orson Welles referred to him as “the most beloved actor of our time.” It was probably an exaggeration, but not by much; Barrymore’s stock in trade was playing cantankerous old codgers with hearts of gold. Ironic, then, that the only role for which he’s widely remembered today is Old Man Potter in It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), one of the most thoroughly heartless characters in the history of movies. In his own day Barrymore was more closely identified with wise old Dr. Gillespie in MGM’s Dr. Kildare series, and with his annual holiday performances as Ebenezer Scrooge on radio. In fact, Barrymore had been slated to play Scrooge in MGM’s A Christmas Carol (1938) until he broke his hip in an auto accident. That injury landed him in a wheelchair, then advancing arthritis kept him there for the rest of his career — until Down to the Sea in Ships.“He had everything wrong with him, most of it in his head…I said, “You’re not sick, you’re just destroying yourself…I have no sympathy for you. You’re a glutton, you drink too much…You want to destroy yourself, you’re really doing it.”

“We finish the picture, he walked off the set. No wheelchair. No crutches. And he came to me and said, “Mr. Hathaway, I want to tell you, you did more for me and for my life on this picture than ever happened to me before. From my father or my mother, or from anybody. I was just simply sitting there and waiting to die.”

Hathaway went on to say that they remained friends for the rest of Barrymore’s life. In any case, whatever the validity of Hathaway’s recollection, the evidence is there on screen: Barrymore responded — whether out of spite or chagrin — by giving one of his strongest performances in years. For once he’s not merely being wheeled around the set acting crusty (although in his more physically active shots he was often doubled by assistant director Richard Talmadge).

I don’t mean to minimize the genuine pain Barrymore surely suffered, but that wheelchair must have been a real convenience for a man who had never been all that crazy about being an actor to begin with. In youth, his real interests were in painting, writing, and composing music, but the pressure to enter the family trade (and the money to be made from it) kept him on stage, screen and radio for nearly sixty years. The role of Capt. Bering Joy was a recognizable “Lionel Barrymore type”, but it was also a complex and vigorous character betrayed by age and ill health, and Barrymore the self-described ham connected with it on a more profound level than almost any part he ever played. He deserves to be remembered for this performance as much as — indeed, more than — for the unalloyed wickedness of Henry Potter.

Down to the Sea in Ships was Richard Widmark’s fifth movie, after his sensational debut as the giggling psycho killer Tommy Udo in Hathaway’s Kiss of Death (1947). In the intervening three pictures, Widmark played a woman-beating gang lord (The Street with No Name), a murderously jealous bar owner (Road House) and an underhanded western outlaw (Yellow Sky). The studio realized he was in danger of being typecast as a succession of nutjobs, sleazeballs and unsavories (because he played them so well), when what the studio really needed was another leading man. Casting him as Dan Lunceford was a conscious effort to help him segue into more sympathetic roles. It worked. Widmark went on to be one of Fox’s most stalwart leading men, playing good guys (Slattery’s Hurricane, Panic in the Streets), bad guys (No Way Out, O. Henry’s Full House) and guys in between (Pickup on South Street, Don’t Bother to Knock) — until, like many other stars, he went free-agent in the mid-1950s.

Down to the Sea in Ships was Richard Widmark’s fifth movie, after his sensational debut as the giggling psycho killer Tommy Udo in Hathaway’s Kiss of Death (1947). In the intervening three pictures, Widmark played a woman-beating gang lord (The Street with No Name), a murderously jealous bar owner (Road House) and an underhanded western outlaw (Yellow Sky). The studio realized he was in danger of being typecast as a succession of nutjobs, sleazeballs and unsavories (because he played them so well), when what the studio really needed was another leading man. Casting him as Dan Lunceford was a conscious effort to help him segue into more sympathetic roles. It worked. Widmark went on to be one of Fox’s most stalwart leading men, playing good guys (Slattery’s Hurricane, Panic in the Streets), bad guys (No Way Out, O. Henry’s Full House) and guys in between (Pickup on South Street, Don’t Bother to Knock) — until, like many other stars, he went free-agent in the mid-1950s.

In Down to the Sea, Widmark is top-billed, although he doesn’t appear until half an hour in. His Dan Lunceford is the character who goes through the most self-surprising changes in the course of the picture. After all, Jed is an adolescent coming of age, and changes are to be expected, while Capt. Joy, though seemingly set in his ways and defiantly so, proves to be flexible, open to change, and willing to learn — when he thinks nobody is watching and he can do it without losing face.

Capt. Joy blusters, but it’s Dan Lunceford who is most nearly arrogant at the outset; part of the reason the captain scoffs at Lunceford’s education is that he senses Lunceford is more than a little puffed-up about it. For his part, Lunceford treats Capt. Joy with an exaggerated politeness that stops just short of insolent sarcasm. (Capt. Joy: “You may have noticed that most of my crew generally sign on again.” Lunceford [drily]: “Out of affection no doubt, sir.”) His sarcasm towards Jed’s lessons, on the other hand, is undisguised — at first. In time, he comes to realize he has misjudged them both, especially the captain. By the end he’s telling Jed that his grandfather is “more of a man than you or I could ever hope to be.” It’s an admission Lunceford could hardly have imagined making when the voyage began.

And then there’s Dean Stockwell. Stockwell’s first screen role came in 1945, when he was eight years old, and he’s still working today — which means that his career has now lasted longer than Lionel Barrymore’s or Richard Widmark’s. When I screened my print of Down to the Sea in Ships for some friends, one of them said, “Dean Stockwell was a revelation!” She was familiar with Stockwell as an adult actor, and knew he had started as a child star, but had no inkling he was ever as good as he is here. (“He was marvelous,” remembered Hathaway, “just a great actor. Intense little guy.”) My friend was right: Dean Stockwell’s performance here is a revelation, easily (at the age of twelve) the best of his career — and for an actor whose résumé includes Gentleman’s Agreement, The Boy with Green Hair, Compulsion, Long Day’s Journey into Night, Blue Velvet, and the TV series Quantum Leap, that’s saying something. Jed Joy is the fulcrum upon which the plot of Down to the Sea in Ships pivots, and in Stockwell’s performance we see him grow from an uncertain, sometimes petulant child into the makings of a fine, strong young man — he seems even to grow taller as the story progresses (and it’s all in his acting; the shooting schedule wasn’t that protracted).

And then there’s Dean Stockwell. Stockwell’s first screen role came in 1945, when he was eight years old, and he’s still working today — which means that his career has now lasted longer than Lionel Barrymore’s or Richard Widmark’s. When I screened my print of Down to the Sea in Ships for some friends, one of them said, “Dean Stockwell was a revelation!” She was familiar with Stockwell as an adult actor, and knew he had started as a child star, but had no inkling he was ever as good as he is here. (“He was marvelous,” remembered Hathaway, “just a great actor. Intense little guy.”) My friend was right: Dean Stockwell’s performance here is a revelation, easily (at the age of twelve) the best of his career — and for an actor whose résumé includes Gentleman’s Agreement, The Boy with Green Hair, Compulsion, Long Day’s Journey into Night, Blue Velvet, and the TV series Quantum Leap, that’s saying something. Jed Joy is the fulcrum upon which the plot of Down to the Sea in Ships pivots, and in Stockwell’s performance we see him grow from an uncertain, sometimes petulant child into the makings of a fine, strong young man — he seems even to grow taller as the story progresses (and it’s all in his acting; the shooting schedule wasn’t that protracted). I’ve been dancing all around something here, and I might as well come right out and say it: Down to the Sea in Ships is a masterpiece. It’s not one of those “miracle pictures” I’ve talked about before, like Peter Ibbetson or A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Making it was no departure for the Hollywood studio system; on the contrary, pictures like this were right up Hollywood’s alley. If there’s a miracle here, it isn’t that it was made in the first place, but that it turned out so well in the end.

I’ve been dancing all around something here, and I might as well come right out and say it: Down to the Sea in Ships is a masterpiece. It’s not one of those “miracle pictures” I’ve talked about before, like Peter Ibbetson or A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Making it was no departure for the Hollywood studio system; on the contrary, pictures like this were right up Hollywood’s alley. If there’s a miracle here, it isn’t that it was made in the first place, but that it turned out so well in the end.If you ever get the chance to see Down to the Sea in Ships, don’t pass it up. I’ve never shown it to anyone who didn’t love it. I guarantee it: this is one of the greatest movies you never heard of.

_______________

*UPDATE 11/4/2021: Down to the Sea in Ships is now available on DVD from 20th Century Fox Cinema Archives; it’s available here from Amazon.

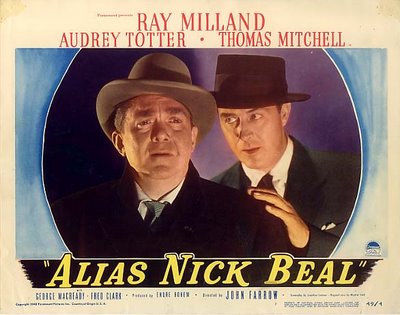

The Paramount mountain dissolves to a slate-colored sky pouring a torrential, whistling rain, riven by claws of lightning and rumbling thunder. There’s a crashing fanfare from composer Franz Waxman that sounds magisterial, commanding and insinuating all at once, then descends into a tortured, frantic violin scherzo. Next the names of the three above-the-title stars — Ray Milland, Audrey Totter, Thomas Mitchell — then the title itself. Alias Nick Beal is under way.

The Paramount mountain dissolves to a slate-colored sky pouring a torrential, whistling rain, riven by claws of lightning and rumbling thunder. There’s a crashing fanfare from composer Franz Waxman that sounds magisterial, commanding and insinuating all at once, then descends into a tortured, frantic violin scherzo. Next the names of the three above-the-title stars — Ray Milland, Audrey Totter, Thomas Mitchell — then the title itself. Alias Nick Beal is under way.

That’s when Foster receives a cryptic summons to a dingy dive down by the waterfront: “If you want to nail Hanson, drop around the China Coast at eight tonight.” The man he meets that night (Ray Milland) is clean-shaven and dapper, impeccably groomed and dressed, cutting a figure entirely at odds with the squalid little tavern where Foster finds him. His card reads simply: “Nicholas Beal, Agent”. “Agent for what?” asks Foster. Beal grins slightly. “That depends. Possibly for you.”

That’s when Foster receives a cryptic summons to a dingy dive down by the waterfront: “If you want to nail Hanson, drop around the China Coast at eight tonight.” The man he meets that night (Ray Milland) is clean-shaven and dapper, impeccably groomed and dressed, cutting a figure entirely at odds with the squalid little tavern where Foster finds him. His card reads simply: “Nicholas Beal, Agent”. “Agent for what?” asks Foster. Beal grins slightly. “That depends. Possibly for you.” Foster decides. He tucks the books under his arm, puts out the light, and makes his way out of the cannery by the beam of a flashlight Beal left behind. In the pitch dark of the outer room, his light startles a rat on a shelf. The rat squeaks plaintively and stares at Foster, eye to eye. We can almost read the rat’s mind, as clearly as if he were speaking: Welcome to my world.

Foster decides. He tucks the books under his arm, puts out the light, and makes his way out of the cannery by the beam of a flashlight Beal left behind. In the pitch dark of the outer room, his light startles a rat on a shelf. The rat squeaks plaintively and stares at Foster, eye to eye. We can almost read the rat’s mind, as clearly as if he were speaking: Welcome to my world.

Naturally, the mainspring of Alias Nick Beal must be Ray Milland’s performance, and he’s nothing short of superb. His Beal is smooth, quiet, confident, glib. Nothing ruffles him. But don’t try to touch him. “I don’t like to be touched.” He says it simply, almost apologetic, but his meaning is clear: you won’t like what happens when you do something Nick Beal doesn’t like. When Beal once flares in anger, it’s over in an instant and his calm demeanor returns, but the moment is unnerving; though his eyes are angry slits in that moment, we can almost see the fires of Hell banked behind them.

Naturally, the mainspring of Alias Nick Beal must be Ray Milland’s performance, and he’s nothing short of superb. His Beal is smooth, quiet, confident, glib. Nothing ruffles him. But don’t try to touch him. “I don’t like to be touched.” He says it simply, almost apologetic, but his meaning is clear: you won’t like what happens when you do something Nick Beal doesn’t like. When Beal once flares in anger, it’s over in an instant and his calm demeanor returns, but the moment is unnerving; though his eyes are angry slits in that moment, we can almost see the fires of Hell banked behind them.

At Cinevent 50 in Columbus, Ohio in 2018, there was a moderated Saturday-afternoon discussion between historians Leonard Maltin and Scott Eyman. At one point, Leonard said of Scott:

At Cinevent 50 in Columbus, Ohio in 2018, there was a moderated Saturday-afternoon discussion between historians Leonard Maltin and Scott Eyman. At one point, Leonard said of Scott: For Archie Leach, the Cary Grant persona was, in Scott’s apt phrase, a brilliant disguise — but it was also a precarious balancing act. Somehow, through some alchemical mix of talent, timing, ambition and luck, this music hall acrobat from Bristol crafted a personality unlike any other. The only child of a feckless alcoholic father and an emotionally unstable mother (young Archie’s father committed her to a mental hospital and told the boy she had died; he didn’t learn the truth for over 20 years), Archie Leach managed to remodel himself into the epitome of urbane sophistication and the greatest romantic comedian in the history of the acting profession.

For Archie Leach, the Cary Grant persona was, in Scott’s apt phrase, a brilliant disguise — but it was also a precarious balancing act. Somehow, through some alchemical mix of talent, timing, ambition and luck, this music hall acrobat from Bristol crafted a personality unlike any other. The only child of a feckless alcoholic father and an emotionally unstable mother (young Archie’s father committed her to a mental hospital and told the boy she had died; he didn’t learn the truth for over 20 years), Archie Leach managed to remodel himself into the epitome of urbane sophistication and the greatest romantic comedian in the history of the acting profession.  Well, that was then, this is now, and I’m breaking that rule again to discuss another contemporary movie and another long shadow. The movie is Mank, directed by David Fincher from a script by his father Jack, and the shadow belongs to Citizen Kane (1941). The younger Fincher appears to have undertaken Mank as a tribute to his father, who died in 2003 (the movie is dedicated to his memory). Besides that, it fits into the intermittent vogue for making movies about the making of movies — that is, about the making of specific movies. It’s a sub-genre that dates back at least as far as 1980’s TV movie The Scarlett O’Hara War, in which 55-year-old Tony Curtis played the 35-year-old David O. Selznick beating the bushes to find a leading lady for Gone With the Wind. The vogue has cropped up from time to time ever since; examples include the aforementioned Saving Mr. Banks and 2012’s Hitchcock, about the making of Psycho. Even Citizen Kane‘s production has been done before, in RKO 281 (1999), with Liev Schreiber as Orson Welles and James Cromwell as William Randolph Hearst.

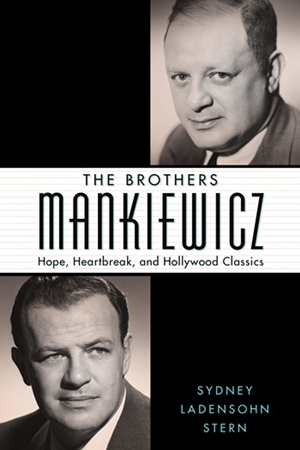

Well, that was then, this is now, and I’m breaking that rule again to discuss another contemporary movie and another long shadow. The movie is Mank, directed by David Fincher from a script by his father Jack, and the shadow belongs to Citizen Kane (1941). The younger Fincher appears to have undertaken Mank as a tribute to his father, who died in 2003 (the movie is dedicated to his memory). Besides that, it fits into the intermittent vogue for making movies about the making of movies — that is, about the making of specific movies. It’s a sub-genre that dates back at least as far as 1980’s TV movie The Scarlett O’Hara War, in which 55-year-old Tony Curtis played the 35-year-old David O. Selznick beating the bushes to find a leading lady for Gone With the Wind. The vogue has cropped up from time to time ever since; examples include the aforementioned Saving Mr. Banks and 2012’s Hitchcock, about the making of Psycho. Even Citizen Kane‘s production has been done before, in RKO 281 (1999), with Liev Schreiber as Orson Welles and James Cromwell as William Randolph Hearst.

Marion Davies went to her grave insisting that she never saw Citizen Kane, and while I’m not sure I believe that, it was her story and she stuck to it to the end. In any case, the idea that she would have driven out to Victorville to sit on the porch critiquing the fine points of Mankiewicz’s script before shooting even started is just plain stupid.

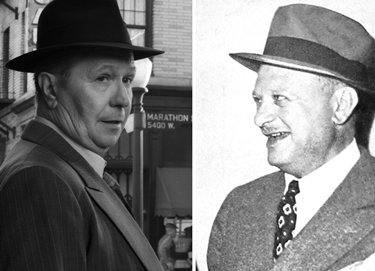

Marion Davies went to her grave insisting that she never saw Citizen Kane, and while I’m not sure I believe that, it was her story and she stuck to it to the end. In any case, the idea that she would have driven out to Victorville to sit on the porch critiquing the fine points of Mankiewicz’s script before shooting even started is just plain stupid. There’s hardly a detail too minor for the movie to go out of its way to get wrong. Herman Mankiewicz had a mustache in 1940. Marion Davies was sweet and well-loved, but she drank too much and, having retired from the screen in 1937, she was puffy and tending to overweight by 1939; also, she stuttered. As for Rita Alexander, no Englishwoman then, or Englishman either, would have used the word “shitty” in mixed company, even if they did think aircraft carriers were “a shitty idea” (which nobody did). That word was a pure Americanism – and for that matter, even in America few women would have said it in those days. The road accident that broke Mankiewicz’s leg happened not because a letter fluttered out of his convertible with the top down, but because Tommy Phipps, who was driving, lost control of the car in the rain on Route 66. The Mankiewicz brothers never called each other “Hermie” and “Joey”, and nobody on Planet Earth was dumb enough to call William Randolph Hearst “Willie”, even behind his back in a soundproof room.

There’s hardly a detail too minor for the movie to go out of its way to get wrong. Herman Mankiewicz had a mustache in 1940. Marion Davies was sweet and well-loved, but she drank too much and, having retired from the screen in 1937, she was puffy and tending to overweight by 1939; also, she stuttered. As for Rita Alexander, no Englishwoman then, or Englishman either, would have used the word “shitty” in mixed company, even if they did think aircraft carriers were “a shitty idea” (which nobody did). That word was a pure Americanism – and for that matter, even in America few women would have said it in those days. The road accident that broke Mankiewicz’s leg happened not because a letter fluttered out of his convertible with the top down, but because Tommy Phipps, who was driving, lost control of the car in the rain on Route 66. The Mankiewicz brothers never called each other “Hermie” and “Joey”, and nobody on Planet Earth was dumb enough to call William Randolph Hearst “Willie”, even behind his back in a soundproof room. Late in the movie, I think at the climax (such as it was), there was a long scene in the “Refectory” at San Simeon (although in Messerschmidt’s hands it just looked like a rather well-furnished cave). The scene seemed to be terribly important; anyhow, it had Gary Oldman going tooth-and-nail for his second Oscar. But by that time the movie had completely lost me and I was no longer even pretending to pay attention; I just sat there rolling my eyes and making that wrist-rotating gesture that is the universal signal for let’s-wind-this-thing-up-already. (I couldn’t help remembering something Pauline Kael wrote in one of her reviews: “Sitting in the darkened theater, I kept listening for snorts, but every time I heard one I could feel the breath on my hands.”) Somewhere in this seemingly-terribly-important scene, Mankiewicz puked and made his famous wisecrack about the white wine coming up with the fish (which actually happened at the home of Arthur Hornblow Jr.), but that’s really all I remember. I was just marking time, waiting for this ridiculous, fraudulent movie to be over. And then…finally…it was.

Late in the movie, I think at the climax (such as it was), there was a long scene in the “Refectory” at San Simeon (although in Messerschmidt’s hands it just looked like a rather well-furnished cave). The scene seemed to be terribly important; anyhow, it had Gary Oldman going tooth-and-nail for his second Oscar. But by that time the movie had completely lost me and I was no longer even pretending to pay attention; I just sat there rolling my eyes and making that wrist-rotating gesture that is the universal signal for let’s-wind-this-thing-up-already. (I couldn’t help remembering something Pauline Kael wrote in one of her reviews: “Sitting in the darkened theater, I kept listening for snorts, but every time I heard one I could feel the breath on my hands.”) Somewhere in this seemingly-terribly-important scene, Mankiewicz puked and made his famous wisecrack about the white wine coming up with the fish (which actually happened at the home of Arthur Hornblow Jr.), but that’s really all I remember. I was just marking time, waiting for this ridiculous, fraudulent movie to be over. And then…finally…it was.