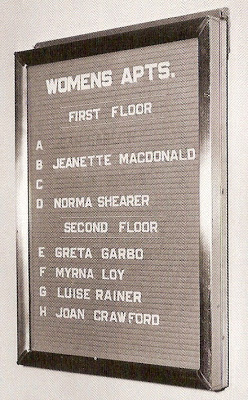

I ended my last post with the shadow of Jean Harlow’s name on the directory outside the star dressing rooms at the MGM studios. It was a ghostly image; the haunting is considerably more tangible in another new book, Harlow in Hollywood: The Blonde Bombshell in the Glamour Capital, 1928-1937 by Darrell Rooney and Mark A. Vieira, published to coincide with the 100th anniversary of Harlow’s birth (March 3, 1911). This sleekly sumptuous coffee-table volume does a great job of evoking both “H”s in the title. I can’t help comparing it to the late Ronald Haver’s David O. Selznick’s Hollywood, even at the risk of overpraising Harlow in Hollywood — at least in my own mind, since I consider Haver’s book just about the best single title ever published on Golden Age Hollywood. There never was such a visual and factual feast as that Selznick book, but Harlow in Hollywood is in the same league.

Rooney and Vieira’s text is essentially an artful paraphrase of David Stenn’s Bombshell: The Life and Death of Jean Harlow, which the authors acknowledge right up front as “the definitive biography” of the star. (By the way, now that I’ve checked out Bombshell‘s Amazon page and seen the prices it’s going for, I guess I’d better never let my 1993 first edition out of my sight!)

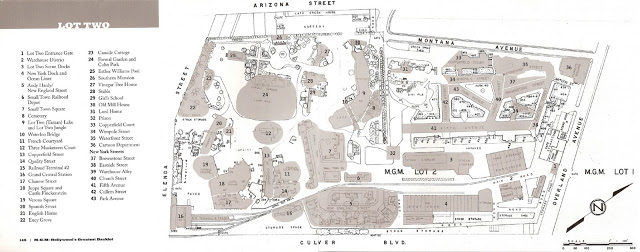

What really set the new book apart are its visuals — the cascade of pictures (there must be 400 or more) from the authors’ own collections and what they’ve garnered from other sources (duly thanked in the acknowledgments), all dazzlingly arranged by designer Hilary Lentini. The evocative beauty of Lentini’s design extends even to the whimsical endpapers, adapted from a 1937 Starland Map and dotted with “pins” marking locations that were significant in Harlow’s life and career. These endpapers go far to conjure up a cozy, sun-soaked little cluster of everybody-knows-everybody communities — Hollywood, Westwood, Beverly Hills, Laurel Canyon — that’s a far cry from the cramped, smoggy, seedy melange of urban sprawl, faded glory and retro kitsch that greets visitors to the L.A. Basin today. (Of course, the map probably had more than a touch of gaga fantasy even then.)

If Harlow in Hollywood doesn’t quite match the visual splash of David O. Selznick’s Hollywood, it’s probably because it doesn’t have the Haver book’s riot of eye-popping color. Which is only fitting: Selznick was an early champion of Technicolor and used it when others told him he was a fool to waste the money; but Selznick figured color would pay off in the long run by adding shelf life to his pictures (and he was right).

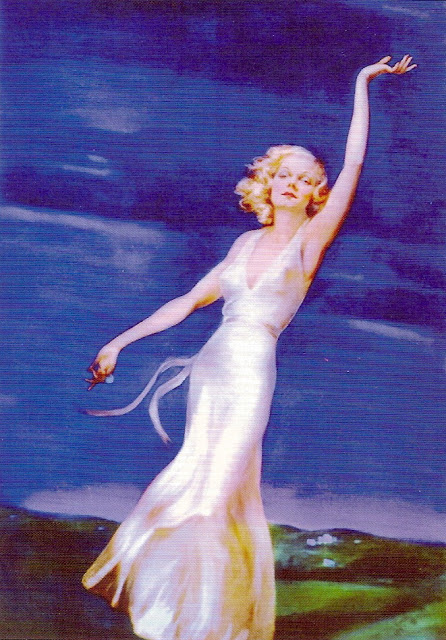

Not that there isn’t color in Harlow in Hollywood — like these striking Carbro color images taken by George Hurrell in late 1935 or early ’36. These pictures are from her “brownette” period late in her career (nobody knew how late), when MGM sought to placate the Breen Office by softening the erotic edge of her platinum blonde image. It’s not as if they had much choice. Harlow’s hair really had that white-blonde sheen in childhood and adolescence (and she was only 17 when she started in pictures), but every blonde’s hair color deepens and thickens with maturity, and Harlow was no exception. Stringent efforts to retain that platinum blonde look — peroxide, ammonia, Lux flakes — had ravaged her scalp and hair to the point where she was in real danger of going bald. I suspect part of the reason for the Hurrell portraits was to prepare Harlow’s fans for her new look.