In Child Star Shirley says that after the release of Little Miss Broadway Darryl Zanuck announced that her next picture would be an adaptation of Lady Jane by Mrs. Cecilia Viets Jamison. Published around the turn of the 20th century (1903, as near as I can tell), the novel told the Dickensian tale of an orphan girl in New Orleans of the 1890s. Little Jane and her gravely ill mother, having fallen on hard times, are taken in by a Mme. Jozain, who, seeing the fine clothes in their luggage, calculates that she’ll be well compensated for nursing the mother back to health. But the mother dies, leaving the girl in Mme. Jozain’s hands to be exploited and abused, her only friend a blue heron.

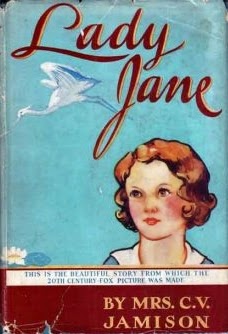

All ends happily, of course, but we needn’t go into it any deeper than that. In trolling around the Internet looking for information on the book — it’s apparently out of print, but used copies are widely available — I found this. It’s a 1935 edition published by Grosset & Dunlap, a firm that often published movie novelizations and “motion picture editions” of classic books. As you can see, the dust jacket says, “This is the beautiful story from which the 20th Century Fox picture was made”. However, Grosset & Dunlap seem to have jumped the gun; Lady Jane was never filmed, with Shirley or anybody else. Could it be that Fox purchased the book as early as 1935, anticipating making a movie, even though Shirley doesn’t mention it coming up until three years later?

In any case, nothing ever came of Lady Jane. Other titles were tossed in the hopper, including one suggested casually by U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau over lunch with Shirley and her mother: The Little Diplomat. On Zanuck’s orders, The Little Diplomat got as far as a treatment by studio writer Charles Beldon and a first draft by Eddie Moran, then withered on the vine. Another proposal, the 1936 children’s novel Susannah of the Mounties by Canadian Muriel Denison, went the distance, as we’ll see later. But for now, in the fall of 1938, Fox yet again turned to an old Mary Pickford vehicle. This time more than just the title would be used, and curiously enough, the story had some elements in common with Lady Jane. The result would be the glittering apotheosis of Shirley’s career at 20th Century Fox.

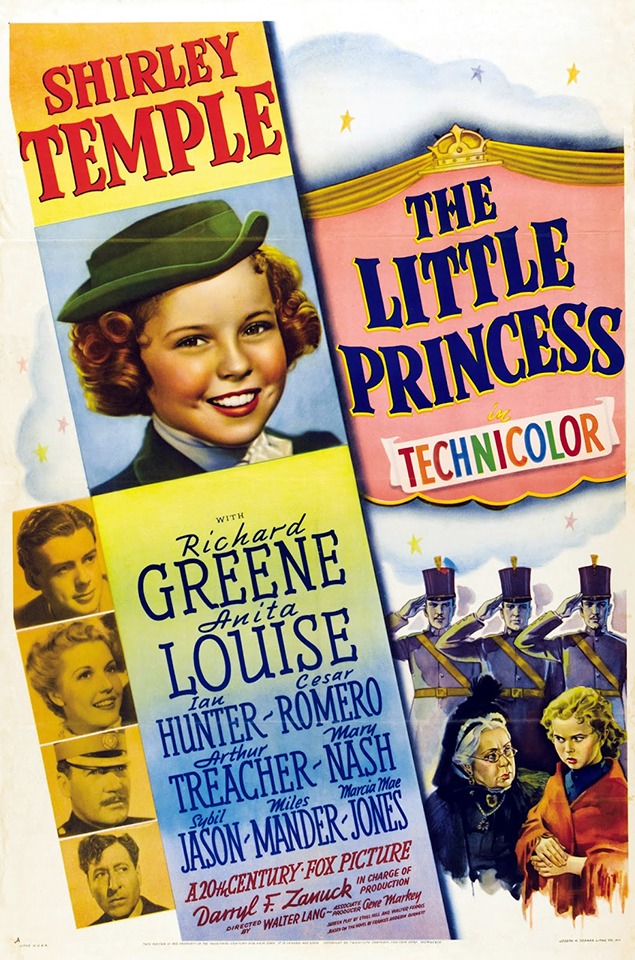

The Little Princess

(released March 10, 1939)

Unlike Lady Jane, A Little Princess has never been out of print since it was first published in 1905. It was the work of Frances Hodgson Burnett, who was born in England in 1849 but lived much of her adult life in the U.S., where she became a citizen in 1905, and where she died and was buried in 1924. She began writing short fiction for magazines while still in her teens, later progressing to romantic novels for adults and sentimental books for children. Her books sold well all her life, enabling her to support a transatlantic lifestyle with homes at various times in America, in England and on the Continent. Her adult novels were all popular in their day, but it’s for her children’s books that she remains best remembered, specifically Little Lord Fauntleroy (1885), The Secret Garden (1911) and A Little Princess.

Unlike Lady Jane, A Little Princess has never been out of print since it was first published in 1905. It was the work of Frances Hodgson Burnett, who was born in England in 1849 but lived much of her adult life in the U.S., where she became a citizen in 1905, and where she died and was buried in 1924. She began writing short fiction for magazines while still in her teens, later progressing to romantic novels for adults and sentimental books for children. Her books sold well all her life, enabling her to support a transatlantic lifestyle with homes at various times in America, in England and on the Continent. Her adult novels were all popular in their day, but it’s for her children’s books that she remains best remembered, specifically Little Lord Fauntleroy (1885), The Secret Garden (1911) and A Little Princess.

The dream fantasy is a pure Hollywood touch, but it works for the picture rather than crippling it, as “In Our Little Wooden Shoes” had done to Heidi. In Heidi, there was no way we could believe that this little Swiss urchin would fantasize herself as a Dutch girl clomping around by the Zuider Zee in her wooden shoes, much less promenading through a stately minuet at the Palace of Versailles. But the fantasy here is entirely in keeping with the Sara Crewe we’ve come to know; for that matter, it’s consistent with the novel’s original Sara Crewe as well. Before Sara’s fall from grace, everyone at the school calls her a “little princess” (some, the mean and spiteful ones, sarcastically); after her fall, it becomes even more important to Sara to be “a princess inside” and take whatever mistreatment Miss Minchin can fling at her with the grace and dignity that implies. So in her dream we see Sara as she sees herself, dispensing justice to the good and wicked alike. The scene also illustrates Sara’s greatest asset in adversity: her vivid imagination. (The “Ali Baba” sequence in the Mary Pickford version tried to do the same, but it went on more than twice as long — in a movie that was half an hour shorter — and bore no connection to Sara’s waking life.)

For Shirley’s next outing, it was back to black-and-white, and a follow-through on one of the projects that had been back-burnered in favor of The Little Princess.

Susannah of the Mounties

(released June 23, 1939)

We needn’t spend much time on Susannah of the Mounties. Muriel Denison’s novel, published in 1936, was the first of four she would eventually turn out; the sequels were Susannah of the Yukon, Susannah at Boarding School and Susannah Rides Again. This first book told of a nine-year-old Canadian girl in 1896 sent to live with her uncle when her parents are assigned to a remote corner of the British Empire. The uncle, an officer at a Royal Canadian Mounted Police outpost in the wilds of Saskatchewan, is at first surprised and unwelcoming, but Susannah soon wins his heart, along with those of everyone else on the post. My own copy of the book is still on order; when I’ve had a chance to look it over, if there’s anything more to be said about it, I’ll post an update here.

But I suspect there won’t be, because once again 20th Century Fox jettisoned everything except the title. The script was credited to Robert Ellis and Helen Logan (story by Fidel La Barba and Walter Ferris), but several other writers put their oars in without credit — never a good sign. Yet again, Shirley played an orphan: Susannah Sheldon, sole survivor of a wagon train massacred by renegade Blackfeet Indians in the 1880s. She is found by Mountie Randolph Scott out on patrol, and more or less adopted by him. From her place on the post she becomes embroiled in tensions between the Canadian Pacific Railroad and the Blackfeet tribe, especially after she befriends the son of a Blackfeet chief sent to the post as a hostage against good behavior. Together Susannah and Little Chief (played by a 13-year-old Blackfeet youth named Martin Good Rider) intervene with his father Big Eagle (Maurice Moscovich) to thwart the warmongering of the villainous Wolf Pelt (Victor Jory) and “show White Man and Indian how to live as brothers.” Peace pipe smoked, fade out.

That’s about it. There’s a perfunctory romance between Susannah’s guardian Inspector Angus “Monty” Montague (Scott) and his commanding officer’s daughter (Margaret Lockwood) that falls somewhere between the similar subplot of Wee Willie Winkie and the one of The Little Princess; otherwise Susannah of the Mounties has the mediocre look and feel of a B-western (albeit spiced up with stock footage from earlier, more expensive Fox westerns). There’s also an attitude toward Canada’s native tribes that’s almost as uncomfortable today as the treatment of African Americans in The Little Colonel and The Littlest Rebel. “Ugh!” is a common line of dialogue given to Blackfeet characters; other lines include “Little Chief not sleep White Man house,” and, so help me, “Devil child have forked tongue!”

Reviews were dismissive, with an air of disappointment, as if the reviewers’ hopes had been raised by The Little Princess, only to be dashed. Variety called Susannah “weakest in the Temple series for some time”, adding, ominously: “Youngster is growing up fast, and is losing some of that sparkle displayed as a tot which carried her so far as a b.o. bet.” B.R. Crisler in the Times, noting the movie’s Mounties in their pillbox hats instead of the familiar peaked campaign hats, cracked: “The early Canadian Northwest Mounted Police certainly wore tricky uniforms, though. Except for the fact that they are on the screen, people at the Roxy might almost mistake them for ushers.” The New Yorker’s John Mosher put it succinctly, and correctly: “The whole offering must be considered as very minor Temple.”

Susannah of the Mounties was directed by Wiliam A. Seiter, one of Shirley’s favorites, who had already directed her in Stowaway and Dimples. Some scenes were directed without credit by Walter Lang (Seiter had performed the same fill-in duty on The Little Princess when director Lang left on “medical furlough”). Shirley’s next picture would reunite her with Lang. Once again, Shirley and Lang would be working in Technicolor, and the production would be, if anything, even more lavish than The Little Princess. Results, however, would differ sharply. For the first time, a Shirley Temple picture would lose money.

Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm was another of Shirley’s “no trace” pictures, like

Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm was another of Shirley’s “no trace” pictures, like  Little Miss Broadway was the one Shirley called “unfailingly bland”, and that about sums it up. Shirley is once again an orphan, this time moving from her orphanage to live with a friend of her late parents (Edward Ellis) who runs a hotel for entertainers. The curmudgeon this time is the rich old landlady next door (Edna May Oliver, her middle name misspelled as “Mae”), who not only plots to get rid of those unsavory show people by selling their hotel out from under them, but (channeling Sara Haden’s truant officer from Captain January) moves to have Shirley returned to her orphanage. Meanwhile, her playboy nephew (George Murphy) is charmed by Shirley and smitten with Ellis’s daughter (Phyllis Brooks of Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm) and tries to thwart the old girl. It all ends in the courtroom of judge Claude Gillingwater, with Shirley and her troupers proving that they’ve got a moneymaking show on their hands and can afford to keep the hotel open.

Little Miss Broadway was the one Shirley called “unfailingly bland”, and that about sums it up. Shirley is once again an orphan, this time moving from her orphanage to live with a friend of her late parents (Edward Ellis) who runs a hotel for entertainers. The curmudgeon this time is the rich old landlady next door (Edna May Oliver, her middle name misspelled as “Mae”), who not only plots to get rid of those unsavory show people by selling their hotel out from under them, but (channeling Sara Haden’s truant officer from Captain January) moves to have Shirley returned to her orphanage. Meanwhile, her playboy nephew (George Murphy) is charmed by Shirley and smitten with Ellis’s daughter (Phyllis Brooks of Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm) and tries to thwart the old girl. It all ends in the courtroom of judge Claude Gillingwater, with Shirley and her troupers proving that they’ve got a moneymaking show on their hands and can afford to keep the hotel open. If Little Miss Broadway was an A-minus picture, Just Around the Corner was no more than a B-plus. If that. Shirley plays Penny Hale, who is taken out of private school when her widowed architect father (Charles Farrell) loses his job, and consequently the penthouse he and Penny have been living in, as well as the money to pay for her school. He’s now forced to work as the electrician in the apartment building where they formerly occupied the penthouse, and he and Penny must now make do with a tiny apartment in the basement.

If Little Miss Broadway was an A-minus picture, Just Around the Corner was no more than a B-plus. If that. Shirley plays Penny Hale, who is taken out of private school when her widowed architect father (Charles Farrell) loses his job, and consequently the penthouse he and Penny have been living in, as well as the money to pay for her school. He’s now forced to work as the electrician in the apartment building where they formerly occupied the penthouse, and he and Penny must now make do with a tiny apartment in the basement. So far we’ve taken Shirley up to the middle of 1937. She’s been Hollywood’s top box-office star for two years, and she’ll go on to be for two years more. This is probably a good time to deal with one of Hollywood’s most persistent and tantalizing legends: Is it true that Shirley Temple was originally set to play Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz? The short answer is: No, but there may be a complicated grain of truth to the legend. In fact, given Shirley’s stature in the industry during the mid-to-late 1930s, it’s unlikely that there wouldn’t be something to it.

So far we’ve taken Shirley up to the middle of 1937. She’s been Hollywood’s top box-office star for two years, and she’ll go on to be for two years more. This is probably a good time to deal with one of Hollywood’s most persistent and tantalizing legends: Is it true that Shirley Temple was originally set to play Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz? The short answer is: No, but there may be a complicated grain of truth to the legend. In fact, given Shirley’s stature in the industry during the mid-to-late 1930s, it’s unlikely that there wouldn’t be something to it. According to Variety, Heidi was chosen for Shirley by public demand, as expressed in her fan mail — although the showbiz bible may simply have been parroting a studio press release. Either way, the role was a natural for Shirley. The source was a novel by Johanna Spyri (1827-1901), first published in the author’s native Switzerland in 1880. The book was instantly popular, and promptly translated from its original German into virtually every written language on Earth. The book was — and remains — so popular, in fact, that it’s surprising to realize that Shirley’s picture in 1937 was the first attempt to make a movie out of it (there have been over a dozen since).

According to Variety, Heidi was chosen for Shirley by public demand, as expressed in her fan mail — although the showbiz bible may simply have been parroting a studio press release. Either way, the role was a natural for Shirley. The source was a novel by Johanna Spyri (1827-1901), first published in the author’s native Switzerland in 1880. The book was instantly popular, and promptly translated from its original German into virtually every written language on Earth. The book was — and remains — so popular, in fact, that it’s surprising to realize that Shirley’s picture in 1937 was the first attempt to make a movie out of it (there have been over a dozen since).

Then disaster strikes — incredibly enough, in the form of exactly the sort of thing Darryl Zanuck said he didn’t want in Wee Willie Winkie. As Heidi and her grandfather sit at their cabin table, he ostensibly begins reading her a story about “The Magic Wooden Shoes”. The camera moves in on a woodcut in the book, and the picture dissolves to a quaint little Dutch scene by a storybook Zuider Zee, and there’s Shirley — or is it Heidi? — in blonde braids and bangs and a starched cap, singing about her shoes:

Then disaster strikes — incredibly enough, in the form of exactly the sort of thing Darryl Zanuck said he didn’t want in Wee Willie Winkie. As Heidi and her grandfather sit at their cabin table, he ostensibly begins reading her a story about “The Magic Wooden Shoes”. The camera moves in on a woodcut in the book, and the picture dissolves to a quaint little Dutch scene by a storybook Zuider Zee, and there’s Shirley — or is it Heidi? — in blonde braids and bangs and a starched cap, singing about her shoes:  But looking back, we can see the handwriting on the wall. For me, seeing Heidi again for the first time in nearly 60 years was an eye-opening shock. I had remembered it as one of Shirley’s best-loved pictures. In fact, it always perplexed me that the 1952 Swiss version, which I saw about the same time, stayed fresher in my memory over the decades. Seeing Shirley’s again, I’m no longer perplexed. Heidi is no doubt one of her best-loved pictures, but it’s not one of her best. Despite those very good early scenes, and some later ones like the scene where the grandfather accompanies Heidi to the church that he hasn’t visited in years (straight out of Frau Spyri’s novel), the picture never recovers from the miscalculation of “In Our Little Wooden Shoes”; it’s one of the head-scratching what-on-Earth-were-they-thinking moments of 1930s Hollywood. What they were thinking, I suspect — or more to the point, what Darryl Zanuck was thinking — was that his dictum about writing the story as if it were a Little Women or David Copperfield, about writing for Shirley as an actress and not depending on any of her tricks, was no longer operative. Henceforth, as far as 20th Century Fox was concerned, Shirley’s tricks would be her stock in trade. The studio was no longer interested in Shirley becoming an actress; instead, they would keep her a baby taking a bow for as long as they could get away with it.

But looking back, we can see the handwriting on the wall. For me, seeing Heidi again for the first time in nearly 60 years was an eye-opening shock. I had remembered it as one of Shirley’s best-loved pictures. In fact, it always perplexed me that the 1952 Swiss version, which I saw about the same time, stayed fresher in my memory over the decades. Seeing Shirley’s again, I’m no longer perplexed. Heidi is no doubt one of her best-loved pictures, but it’s not one of her best. Despite those very good early scenes, and some later ones like the scene where the grandfather accompanies Heidi to the church that he hasn’t visited in years (straight out of Frau Spyri’s novel), the picture never recovers from the miscalculation of “In Our Little Wooden Shoes”; it’s one of the head-scratching what-on-Earth-were-they-thinking moments of 1930s Hollywood. What they were thinking, I suspect — or more to the point, what Darryl Zanuck was thinking — was that his dictum about writing the story as if it were a Little Women or David Copperfield, about writing for Shirley as an actress and not depending on any of her tricks, was no longer operative. Henceforth, as far as 20th Century Fox was concerned, Shirley’s tricks would be her stock in trade. The studio was no longer interested in Shirley becoming an actress; instead, they would keep her a baby taking a bow for as long as they could get away with it.  Calling the picture “Rudyard Kipling’s” Wee Willie Winkie was a bit of an overstatement. The original story was published in 1888, when the future Nobel Prize winner was 22. It told of Percival William Williams, the six-year-old son of an army colonel stationed with his regiment in British India at the foot of the Khyber Pass on the indistinct border with Afghanistan. Percival has a penchant for nicknaming people, including himself, so he has adopted the name Wee Willie Winkie from one of his nursery-books. Winkie is bright but typically mischievous for a boy his age, and under the military discipline imposed by his father he is forever earning, then forfeiting, a succession of Good Conduct Badges.

Calling the picture “Rudyard Kipling’s” Wee Willie Winkie was a bit of an overstatement. The original story was published in 1888, when the future Nobel Prize winner was 22. It told of Percival William Williams, the six-year-old son of an army colonel stationed with his regiment in British India at the foot of the Khyber Pass on the indistinct border with Afghanistan. Percival has a penchant for nicknaming people, including himself, so he has adopted the name Wee Willie Winkie from one of his nursery-books. Winkie is bright but typically mischievous for a boy his age, and under the military discipline imposed by his father he is forever earning, then forfeiting, a succession of Good Conduct Badges. Needless to say, in Ernest Pascal and Julien Josephson’s screenplay nearly all of this was changed. Percival was changed to Priscilla and given a widowed American mother (June Lang). The colonel backs up a generation, becoming Priscilla’s grandfather (C. Aubrey Smith), who sends for Priscilla and her mother when he learns they are living in poverty in America. Priscilla is still nicknamed Wee Willie Winkie, but her military discipline is self-imposed in an effort to become a soldier, since that seems to be the only type of person her grandfather the colonel likes. “Private” Winkie still takes a shine to Lt. “Coppy” Brandis (Michael Whalen, Shirley’s father in Poor Little Rich Girl), but he throws over Maj. Allardyce’s daughter to romance Winkie’s mother. While he’s doing that, Coppy’s duties as Winkie’s best friend among the soldiery devolve onto a new character, Sergeant MacDuff (Victor McLaglen).

Needless to say, in Ernest Pascal and Julien Josephson’s screenplay nearly all of this was changed. Percival was changed to Priscilla and given a widowed American mother (June Lang). The colonel backs up a generation, becoming Priscilla’s grandfather (C. Aubrey Smith), who sends for Priscilla and her mother when he learns they are living in poverty in America. Priscilla is still nicknamed Wee Willie Winkie, but her military discipline is self-imposed in an effort to become a soldier, since that seems to be the only type of person her grandfather the colonel likes. “Private” Winkie still takes a shine to Lt. “Coppy” Brandis (Michael Whalen, Shirley’s father in Poor Little Rich Girl), but he throws over Maj. Allardyce’s daughter to romance Winkie’s mother. While he’s doing that, Coppy’s duties as Winkie’s best friend among the soldiery devolve onto a new character, Sergeant MacDuff (Victor McLaglen).

Seen today, Wee Willie Winkie bears out Shirley’s opinion more than it does Mosher’s, Flin’s or Nugent’s. The picture is certainly not too long. Children may squirm during the protracted love scenes between Michael Whalen and June Lang, but so do adults. Both were bland Fox contract players on an unstoppable career path toward B pictures and, at the onset of middle age, television. Whalen’s dark good looks were about to be rendered irrelevant by the rise of the far more charismatic Tyrone Power. As for Lang (Shirley’s “mother” was only 11 years older than she was), within seven years she would be a nameless, uncredited “Goldwyn Girl” behind Danny Kaye in Up in Arms, and would finish her career with one-off guest shots on TV cop shows in the ’50s and ’60s. Whalen and Lang were (and remain) attractive and inoffensive, but they lack the chemistry — with either the audience or each other — that Robert Young and Alice Faye showed in Stowaway, or Faye and Jack Haley in Poor Little Rich Girl. (The blue-green of this frame-cap, like the sepia of others, reproduces the tinted stock Wee Willie Winkie sported on its original release.)

Seen today, Wee Willie Winkie bears out Shirley’s opinion more than it does Mosher’s, Flin’s or Nugent’s. The picture is certainly not too long. Children may squirm during the protracted love scenes between Michael Whalen and June Lang, but so do adults. Both were bland Fox contract players on an unstoppable career path toward B pictures and, at the onset of middle age, television. Whalen’s dark good looks were about to be rendered irrelevant by the rise of the far more charismatic Tyrone Power. As for Lang (Shirley’s “mother” was only 11 years older than she was), within seven years she would be a nameless, uncredited “Goldwyn Girl” behind Danny Kaye in Up in Arms, and would finish her career with one-off guest shots on TV cop shows in the ’50s and ’60s. Whalen and Lang were (and remain) attractive and inoffensive, but they lack the chemistry — with either the audience or each other — that Robert Young and Alice Faye showed in Stowaway, or Faye and Jack Haley in Poor Little Rich Girl. (The blue-green of this frame-cap, like the sepia of others, reproduces the tinted stock Wee Willie Winkie sported on its original release.)

I’m going to pass over Dimples as quickly as duty will allow because, like

I’m going to pass over Dimples as quickly as duty will allow because, like  In Child Star Shirley remembered Frank Morgan’s tireless efforts to upstage her and steal focus during their scenes — fiddling with his cuffs, flourishing his handkerchief, placing his stovepipe hat on a table between her and the camera so that she couldn’t be in the shot without stepping off her mark and out of the light. (“Both of us knew perfectly well what he was doing. There was no way I could cope, short of biting at his fingers.”) Director William A. Seiter was on to Morgan’s tricks too; in this scene, where Dimples sings “Picture Me Without You” (one of four pleasantly forgettable songs provided by Jimmy McHugh and Ted Koehler), Seiter made Morgan sit in a chair with his back to the camera. (“When this picture is over,” cracked producer Nunnally Johnson, “either Shirley will have acquired a taste for Scotch whiskey or Frank will come out with curls.”)

In Child Star Shirley remembered Frank Morgan’s tireless efforts to upstage her and steal focus during their scenes — fiddling with his cuffs, flourishing his handkerchief, placing his stovepipe hat on a table between her and the camera so that she couldn’t be in the shot without stepping off her mark and out of the light. (“Both of us knew perfectly well what he was doing. There was no way I could cope, short of biting at his fingers.”) Director William A. Seiter was on to Morgan’s tricks too; in this scene, where Dimples sings “Picture Me Without You” (one of four pleasantly forgettable songs provided by Jimmy McHugh and Ted Koehler), Seiter made Morgan sit in a chair with his back to the camera. (“When this picture is over,” cracked producer Nunnally Johnson, “either Shirley will have acquired a taste for Scotch whiskey or Frank will come out with curls.”)

Stowaway gave Shirley an exotic setting, a story that didn’t require her to carry the show all by herself, and cast-mates who were strong enough to share the load. Shirley played Barbara Stewart, nicknamed “Ching-Ching”, the orphaned daughter of missionaries in Sanchow, China. At the approach of bandits from the hills, she’s about to be orphaned again — or worse — because her guardians the Kruikshanks (also missionaries) refuse to flee from the approaching marauders. Defying them, the wise local magistrate Sun Lo (Philip Ahn) spirits Ching-Ching away with a boatman to Shanghai.

Stowaway gave Shirley an exotic setting, a story that didn’t require her to carry the show all by herself, and cast-mates who were strong enough to share the load. Shirley played Barbara Stewart, nicknamed “Ching-Ching”, the orphaned daughter of missionaries in Sanchow, China. At the approach of bandits from the hills, she’s about to be orphaned again — or worse — because her guardians the Kruikshanks (also missionaries) refuse to flee from the approaching marauders. Defying them, the wise local magistrate Sun Lo (Philip Ahn) spirits Ching-Ching away with a boatman to Shanghai.

Alice also sang “One Never Knows, Does One?”, another one by Gordon and Revel, this time with no little-girl version for Shirley. Then Shirley closed out the show with “That’s What I Want for Christmas”, written by the uncredited Gerald Marks and Irving Caesar. This last number comes at the very end, after the story has been brought to a satisfying conclusion, and it plays almost like a curtain-call encore. Evidently it was added at the last minute to exploit the movie’s holiday engagement at New York’s Roxy picture palace (it didn’t sift down to the rest of the country until after the turn of 1937).

Alice also sang “One Never Knows, Does One?”, another one by Gordon and Revel, this time with no little-girl version for Shirley. Then Shirley closed out the show with “That’s What I Want for Christmas”, written by the uncredited Gerald Marks and Irving Caesar. This last number comes at the very end, after the story has been brought to a satisfying conclusion, and it plays almost like a curtain-call encore. Evidently it was added at the last minute to exploit the movie’s holiday engagement at New York’s Roxy picture palace (it didn’t sift down to the rest of the country until after the turn of 1937).