With the Christmas Season 2017 upon us, I’m departing once again from my focus on Golden Age Hollywood to share my story “The Sensible Christmas Wish”, first published here last year about this time. Last year’s introduction can be found by clicking here if you’re interested in knowing what I said then — or, if you’d rather, just click on the title and you’ll be taken directly to the story, which came to me from a wise and wonderful older person I once knew. I hope it brings you some of the magic and joy of The Most Wonderful Time of the Year.

Five-Minute Movie Star: Carman Barnes in Hollywood — Epilogue

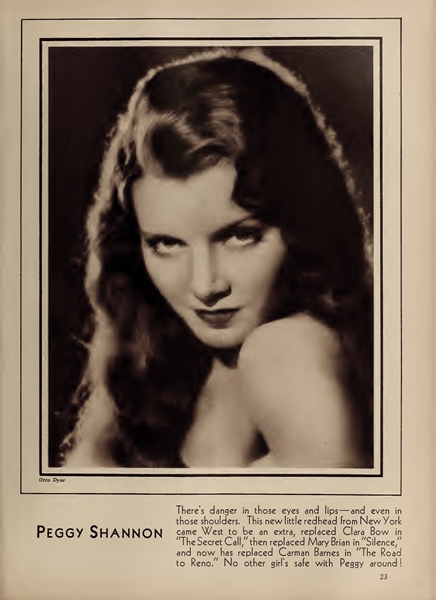

This is the young woman who replaced Carman Barnes on The Road to Reno, as she looked in the November 1931 issue of Motion Picture Magazine. In case the caption on this Otto Dyer glamour shot is too small for you to read, here’s what it says:

This is the young woman who replaced Carman Barnes on The Road to Reno, as she looked in the November 1931 issue of Motion Picture Magazine. In case the caption on this Otto Dyer glamour shot is too small for you to read, here’s what it says:

“There’s danger in those eyes and lips — and even in those shoulders. This new little redhead from New York came West to be an extra, replaced Clara Bow in ‘The Secret Call,’ then replaced Mary Brian in ‘Silence,’ and now has replaced Carman Barnes in ‘The Road to Reno.’ No other girl’s safe with Peggy around!”

Peggy did indeed get a career boost from three high-profile replacement gigs in a row, and she seemed off to a good start. Before we go on to consider why she replaced Carman, let’s pause a moment to see how Peggy’s career worked out for her.

In a word, badly. She turned out to be another sad case — like Sidney Fox, whom she resembled in more ways than one. Born in Arkansas in 1907, she caught Florenz Ziegfeld’s eye while visiting her aunt in New York and became a Ziegfeld Girl at 16 in the Follies of 1923. After a few dry years she started getting steady Broadway work in 1927, until Paramount’s B.P. Schulberg spotted her in Life Is Like That in 1930 and brought her west. Peggy and Carman arrived in Hollywood about the same time (Schulberg may even have signed both deals on the same trip). Two days after Peggy’s arrival, Clara Bow suffered a nervous breakdown and Peggy was pulled off the bench to pinch-hit, apparently on her way to real stardom. But not so fast — after a good couple of years at Paramount, she started bouncing from studio to studio: Warners to Columbia to MGM, with stopovers in between at various indie and Poverty Row outfits. Every step of the way she was followed by rumors of difficult behavior and alcohol abuse, which may explain why she never worked anywhere very long. Then it was back to Broadway in 1934 for Page Miss Glory. Perhaps significantly, when Peggy’s old studio Warner Bros. bought the screen rights to Page Miss Glory, they gave her part to Mary Astor.

Peggy did one more play, got fired from yet another for drunkenness, then was back in Hollywood in 1936 for a parade of B-movies, bit parts and short subjects that kept her sporadically employed until 1940. In the meantime, she drank herself into a diseased liver and a fatal heart attack in May 1941 when she was 34. Less than three weeks later, her husband, Warners cameraman Al Roberts, shot himself in the same kitchen chair where he had found her dead body. He couldn’t bear to be separated from her, but in death he was: they were buried in cemeteries at opposite ends of Los Angeles.

But back to Carman. What happened on The Road to Reno? That’s why I’d like a peek into the Paramount files. Cal York claimed that Carman’s first picture (which he still thought was Strangers and Lovers) was scheduled for an eight-week shoot (“The girl’s lines need much camera attention.”). But if we can believe Motion Picture Herald’s timeline, The Road to Reno was shooting from June 27 to August 1. Five weeks, more or less. And no sooner was it announced as “Completed” (with Carman still attached) than a list of names “On the Dotted Line” was published, with Peggy Shannon where Carman used to be. Can it be that Carman went through the whole shooting schedule, then Paramount, looking at a rough cut, decided to replace her and sent Peggy Shannon in immediately to reshoot her scenes? The Road to Reno was able to make its September 26 release date eight weeks later, so the studio couldn’t have let much grass grow under their feet. I suspect Peggy was Plan B all the time, with Paramount stringing along with Carman to see if she was going to work out, then finally deciding she hadn’t.

What could have been the problem? The most obvious answer would be that she couldn’t act. But really, how bad would she have had to be? Have you seen Jean Harlow at the beginning of her career — in Hell’s Angels, for example? Or for that matter, Kim Novak in anything? No, I don’t think it was that.

Later, looking back from its June 1932 issue, Motion Picture Magazine said Paramount had “discovered that the camera tests weren’t as satisfactory as Carman in person.” And even before the cameras rolled, in his profile in the May ’31 Silver Screen, writer Edward Churchill offered another hint. It was literally an afterthought, tacked on at the tail-end of his largely adoring profile:

Later, looking back from its June 1932 issue, Motion Picture Magazine said Paramount had “discovered that the camera tests weren’t as satisfactory as Carman in person.” And even before the cameras rolled, in his profile in the May ’31 Silver Screen, writer Edward Churchill offered another hint. It was literally an afterthought, tacked on at the tail-end of his largely adoring profile:

“Anything else?

“Oh, yes.

“When Carman talks her eyebrows move — sort of wiggle…”

Wiggling eyebrows, eh? Well now. Churchill described it as part of Carman’s “mysterious quality”, what he called “X” — “exotic, transparent and fascinating…like a vagrant tune from far away or a delicate perfume.” He was talking about Carman in person. But what about on the screen? I can imagine the following scenario:

The Paramount bigwigs get a look at some footage of Carman, either in screen tests or actual rushes from The Road to Reno. Somebody — B.P. Schulberg, maybe, or Jesse Lasky — pipes up: “What’s with those eyebrows? She looks like she’s got a couple of spastic caterpillars on her face.” (What looks like a charming little mannerism sitting across from you in an interview, or even on the set, could look very different projected on a screen twenty feet wide.) Somebody takes Carman aside. “Honey, you’ve got this thing you do with your eyebrows. It looks weird in the rushes.” Carman is surprised and a little affronted; nobody’s ever complained about the way she talks, for God’s sake. But she politely thanks whoever it is, says she’ll fix it.

And she tries, but it keeps getting away from her. Maybe it spoils some takes. “Cut! Carman, eyebrows!” “Cut! Eyebrows, Carman! Jeee-zus…Okay, I’m sorry. Let’s take it again…” Carman gets self-conscious, stiffens up (remember what she said in that letter to Clara Jackson, sending Clara kisses and facetiously “wonder[ing] if her chin’s at the right angle”). More takes, more self-conscious stiffness, ever stiffer, ever more self-conscious. Finally the bigwigs shrug, “She doesn’t come across like she does in person. Tough.”

But who knows? Maybe it wasn’t just the eyebrows — or maybe the eyebrows had nothing to do with it. Anyhow, it’s odd. By the beginning of August, by my count, Paramount had paid Carman $29,100 — hardly chickenfeed in 1931. Why would they write off that much money? To say nothing of shelling out who-knows-how-much more to reshoot with Peggy Shannon? About that same time, there was a bit player starting out at Pathé and MGM named Clark Gable; some people thought his ears were a deal breaker — but they still released the pictures he was in. Carman didn’t get even that much.

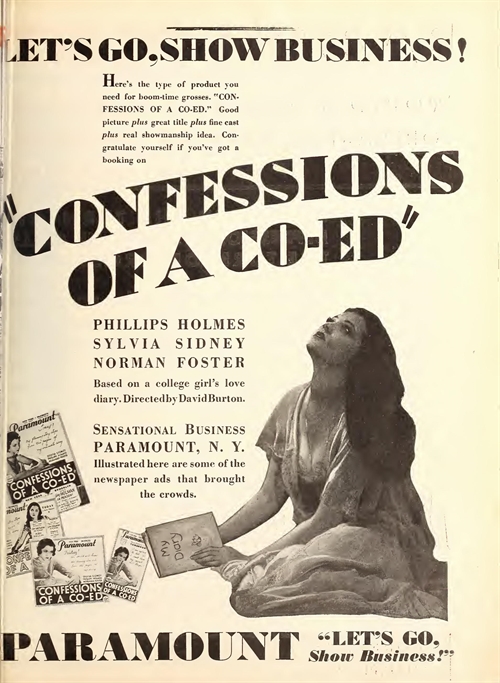

And what about Carman the writer? Cal York said she couldn’t come up with a decent story. But maybe she did — or at least one that made it to the screen. Midway through Carman’s tenure at Paramount, in June, the studio released Confessions of a Co-Ed with Sylvia Sidney, Phillips Holmes, Norman Foster and Claudia Dell. Not only is the title curiously similar to the Confessions of a Débutante (or A Débutante Confesses) that was supposed to be Carman’s first picture, but the story sounds like something she just might have made up. It’s a complicated tale of campus shenanigans. Pat (Sidney) loves campus Romeo Dan (Holmes) and gets pregnant by him. Through a series of misunderstandings, Dan leaves town and Pat traps his friend Hal (Foster) into marriage. Three years later Dan returns and everything comes to a head.

And what about Carman the writer? Cal York said she couldn’t come up with a decent story. But maybe she did — or at least one that made it to the screen. Midway through Carman’s tenure at Paramount, in June, the studio released Confessions of a Co-Ed with Sylvia Sidney, Phillips Holmes, Norman Foster and Claudia Dell. Not only is the title curiously similar to the Confessions of a Débutante (or A Débutante Confesses) that was supposed to be Carman’s first picture, but the story sounds like something she just might have made up. It’s a complicated tale of campus shenanigans. Pat (Sidney) loves campus Romeo Dan (Holmes) and gets pregnant by him. Through a series of misunderstandings, Dan leaves town and Pat traps his friend Hal (Foster) into marriage. Three years later Dan returns and everything comes to a head.

The movie is memorable today mainly as an early bump in Sylvia Sidney’s career and for an appearance by Paul Whiteman’s Rhythm Boys (Bing Crosby, Harry Barris and Al Rinker) as themselves, playing a gig at a campus dance. But here’s the strange thing: the picture has no screenplay credit, not for dialogue or story; the closest thing to it is the blurb in this Motion Picture Herald ad (“based on a college girl’s love diary“). Could Strangers and Lovers (“…a tale of a girl who is afraid she is wicked…”; “…this absorbing drama of an innocent-wise 19-year[-old] charmer…”; “…a strong story of young love that will be long remembered…”) have somehow morphed into Confessions of a Co-Ed? Carman’s contract with Paramount Publix allowed the studio to do whatever they pleased with anything she wrote while she was on the payroll. Did Carman, for the sake of $1,000 a week as the Depression took hold, swallow her resentment when Paramount handed her story off to Sylvia Sidney? Then did she swallow it again, when they cast her in a picture she did not write for herself? And when they replaced her in her first picture after she had already shot it — was that the last straw? Like the bit with the eyebrows, we may never know, but it’s a scenario I can easily imagine.

Of course, I could be wrong. Maybe someday I’ll get a look at the Paramount archives and find out what really happened, and it’ll be simpler, or more complicated, than any of this. All I know now is whatever happened, Carman may have talked about it with family and friends but she never wrote anything down — at least, nothing that survives in her papers at the University of Rochester.

Well…actually, that’s not exactly true. There was that book that Motion Picture and The New Movie Magazine mentioned that she was writing — “in which, rumor has it, she’ll tell tales,” according to New Movie. The book was Mother, Be Careful!, published by Liveright in the fall of 1932. Variety reviewed it in their October 18 issue:

“Just Dull Carman Barnes, who authored ‘School Girl,’ has produced ‘Mother Be Careful’ [sic] which Liveright has put between covers. In a general way the reader gets the impression that the book is supposed to be a satire on Hollywood. At least most of the action is laid there, but it is not very lively action.

“Told mostly in would-be smart dialogue, but seldom hitting the mark. Plotless, pointless and tiresome.”

Variety’s anonymous reviewer was a little harsh. Mother, Be Careful! does indeed read as if it were written in an almighty hurry. There’s little of the careful construction of School Girl and none of the stylistic experimentation of Beau Lover (told in the second person, as if the reader is the protagonist). But there’s an appealing wackiness to Mother, a spirit rather akin to the sort of movies the Marx Brothers were making at Paramount while Carman was working there, and it nicely encapsulates the widespread sense that the lunatics are running the Hollywood asylum. And with all due respect to Variety, Mother, Be Careful! is frequently very funny. The opening paragraph, for example:

“With a deep breath Daisy tightened her brassiere. Just then the taxi hit a bump, and the snap popped. Daisy looked like a startled deer.”

“Daisy” is 18-year-old New Yorker and transplanted southern belle Daisy Andrews, and as the novel opens she’s being squired around Manhattan by one Goldie Bromberg, a high mucky-muck at Wunderbar Pictures. Goldie is trying to persuade Daisy to shack up with him out west in Hollywood, offering her a star contract more or less as an afterthought. Daisy swallows her wide-eyed misgivings on the condition that her mother come with her, though she wonders about the morals out there; do mothers really stand for such shenanigans? Goldie pooh-poohs her: “You’re crazy, baby. Mothers are the only ones in Hollywood who really have a good time. Daughter works all day, Mother plays with Daughter’s men all night.”

So Daisy and Mother set out for Hollywood, where they attend studio meetings by day and parties by night, trying to figure out what they’re really doing here. In time, when the cameras finally roll, Mother — having, shall we say, ingratiated herself with Goldie Bromberg — is playing the lead in a story she wrote herself, with Daisy relegated to the off-screen voice of Mother’s unborn child. Not only that, but the romantic lead is Daisy’s erstwhile would-be lover Carlson Cartwright, an unkempt Bolshevik agitator disdainful of the rampant materialism of Hollywood — until he gets a taste of stardom and the salary that goes with it. Mother’s picture flops (it seems that her story was apparently plagiarized from another studio’s picture), but she is able to blackmail “Bromby” out of his Wunderbar stock, which she then sells back to the studio’s board of directors. In the end mother and daughter desert Hollywood with alacrity and a tidy fortune. “I never want to see Hollywood again,” says Mother. “It is not the place for two Southern gentlewomen, Daisy.” Daisy sighs, “When a girl can look safely back on her Hollywood experiences, she realizes more exactly just what life is for.”

And that, friends, seems to have been Carman Barnes’s last word on the matter.

Does Mother, Be Careful! “tell tales”? Well, maybe. Goldie Bromberg, if you squint at the character sideways, could almost be a near-libelous caricature of B.P. Schulberg, and there’s a pompous martinet director named Josef von Gluck who could even more easily pass for a spoof of Josef von Sternberg, Paramount’s reigning director of the day (C.B. DeMille having temporarily decamped) and no stranger to pomposity himself.

There’s one scene, an impromptu meeting where Daisy and Mother corral Bromberg in the studio barber shop, that fairly bristles with echoes of Carman’s personal experience — Confessions of a Débutante, “by and with Carman Barnes” and so forth:

“What is the secret of a sub-deb?” Goldie demanded with intense interest.

The supervisors held their breath.

Daisy knew her fate hung on her answer. She opened her wide surprised eyes.

“Why—the secret of a sub-deb is that she doesn’t wear a brassiere,” she said.

A sudden quiet descended. Ominous. Profound.

Then a light dawned in Goldie’s eyes. He stared at Daisy with astonished pleasure.

“Boys!”

The supervisors leapt to their feet.

“What a title, boys! what a title! Secrets of a Sub-Deb. And what a sub-title! Intimate revelations of what goes on inside a modern girl’s brassiere.”

“Marve-lous. Marve-lous, Let me congratulate you!” said von Gluck.

“What is your name again?” asked Goldie.

“Just Daisy,” said Daisy brightly.

“Daisy! Daisy? Daisy. No, no. Something more exotic. Taffy Tuhluh.”

“What has chewing gum to do with writing?” asked Daisy.

“Chewing gum? Nothing. Taffy Tuhluh is your new name. Now, Miss Tuhluh, I’m going to put your name in lights, on the lips of thousands of people. I’ve a millon-dollar idea. Secrets of a Sub-Deb, by and with Taffy Tuhluh.”

Daisy choked.

“Wham! Such box office! We’ll sign you up as a by-and-wither immediately. Will you be my little by-and-wither—Daisy?”

By the end of Mother, Be Careful!, little by-and-wither Daisy is gone from Hollywood with a sigh of bemused relief — no doubt much the same way by-and-wither Carman was gone by the end of 1931.

Gone, but not forgotten — not quite and not just yet. Throughout the first half of 1932, Carman’s name kept cropping up in this or that magazine as some sort of cautionary tale. In the July Motion Picture an article by Sonia Lee on the burgeoning stardom of Clark Gable quotes Paramount casting director Fred Datig as saying that a studio can’t make stars — that the public does that. “If there is ability in a player and it shows quickly — then the studio is in luck,” says Datig. “If we find that either we can’t bring it out, or that we might have been mistaken, then the player is let out.” This can only have been a sidelong reference to Paramount’s washing its hands of Carman. But what’s that business about only the public making a star? Doesn’t that imply that only the public can decide when someone’s not going to be a star? The public never got to make that call.

Or did they? Here’s another imaginary scenario: Was The Road to Reno completed and previewed with Carman? Did the preview go so badly that the studio immediately replaced her, commenced reshooting, and hustled her out the Marathon Street gate as fast as they could buy out her contract? It seems unlikely; no hint of a bad preview appears in any of the magazines at the time, and ever since then nobody has known enough to ask. But it might explain Fred Datig’s cryptic comment about the public’s veto power on stardom.

A month before that Sonia Lee article, in the June Motion Picture’s “News and Gossip of the Studios” column, the following teaser item appeared:

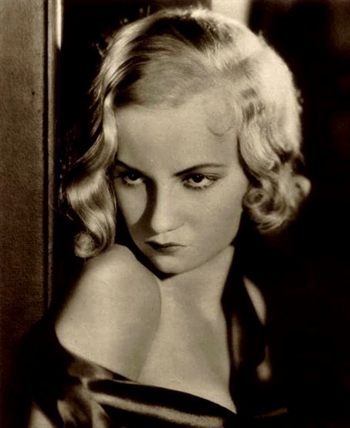

“It’s no more than a whisper to date, but there is a whisper that one of the much-ballyhooed screen discoveries may turn out to be another Carman Barnes. Carman, you remember, was the young authoress who was spotted in the story department of Paramount and hailed as ‘the next star’ by the studio, which later discovered that the camera tests weren’t as satisfactory as Carman in person. Carman quietly vanished, going on the stage. The exotic newcomer resembles Carman slightly — which may have given rise to the whispers.”

Who was this “exotic newcomer” the item compared to vanished, banished Carman? The timing might be right for her to be Sari Maritza (pronounced “Sha-ree Ma-reet-zah”). That’s her on the left; can you see a “slight resemblance” to Carman? Anyhow, she is mentioned by name elsewhere in that same issue as “the ‘second Dietrich’ whom Paramount has under contract” — and who, like Carman a year earlier, “has been here months without starting [a single picture].” By 1932, Paramount was feeling that Marlene Dietrich had gotten too big for those sleek men’s britches she so often wore, and apparently had plans to groom Sari as a replacement. Miss Maritza did eventually appear in a handful of Paramount features, but she turned out not to be star material — and worse, she wasn’t even German. She had made pictures in Germany and was fluent in a number of European languages, but her real name was Dora Patricia Detering-Nathan, born in China to a British Army officer and his Austrian wife, and about as exotic as Picadilly Circus.

Who was this “exotic newcomer” the item compared to vanished, banished Carman? The timing might be right for her to be Sari Maritza (pronounced “Sha-ree Ma-reet-zah”). That’s her on the left; can you see a “slight resemblance” to Carman? Anyhow, she is mentioned by name elsewhere in that same issue as “the ‘second Dietrich’ whom Paramount has under contract” — and who, like Carman a year earlier, “has been here months without starting [a single picture].” By 1932, Paramount was feeling that Marlene Dietrich had gotten too big for those sleek men’s britches she so often wore, and apparently had plans to groom Sari as a replacement. Miss Maritza did eventually appear in a handful of Paramount features, but she turned out not to be star material — and worse, she wasn’t even German. She had made pictures in Germany and was fluent in a number of European languages, but her real name was Dora Patricia Detering-Nathan, born in China to a British Army officer and his Austrian wife, and about as exotic as Picadilly Circus.

Sari Maritza eventually admitted that she couldn’t act and retired from the screen in 1934. But before that, as the so-called “Sari Maritza hoax” was being exposed in October 1932, her masquerade as a sultry Teutonic vamp occasioned the final mention in Hollywood of the departed Carman Barnes. It came, interestingly enough, from Carman’s former Paramount colleague Jack Oakie. “Ha! You can’t fool me!” Oakie is quoted as saying. “That Maritza gal is just Carman Barnes revamped, redecorated, and put back into circulation!”

After that, except for Variety’s pan of Mother, Be Careful!, the Hollywood record falls silent about Carman Barnes. In just under 22 months she had gone from bestselling literary prodigy…to Broadway playwright…to the Next Clara Bow…to an answer in a trivia quiz by Marion Martone…to the punchline of a Jack Oakie wisecrack. And as far as I’ve been able to tell, that suited her just fine.

She was not yet 20 years old.

* * *

Carman Barnes’s movie career may have gone precisely nowhere, but she deserves a place in the history books for her unprecedented Hollywood contract. Never before had a major studio signed a woman to write and star in her own pictures. Given the outcome, it wouldn’t be surprising if it never happened again — but it did, the very next year (1932) and at the very same studio (Paramount). This time the woman in question was Mae West — and this time she made it into the history books.

More than one fan magazine reported (like that June Motion Picture item quoted above) that after leaving Hollywood Carman wound up playing ingenues on the stage. If so, it must have been in regional theaters rather than New York, because I’ve been unable to find any details. Maybe she did a play or two as a lark, or just to be able to say she did it.

In any case, Carman and her mother Diantha wound up back in New York, where Carman promptly exorcised her Hollywood sojourn by writing Mother, Be Careful!. For her next novel, in 1934, Carman brought back Naomi Bradshaw, the heroine of Schoolgirl. Young Woman picks up Naomi as she moves to New York; the Depression has wiped out her family’s prosperity, driving her father to suicide and her mother to despair. Naomi has moved to New York to make her own way and, if possible, rebuild her family’s fortune — if not by marrying well, then by being well-kept.

Having produced four novels in five years, Carman ceased publication for over a decade. But she never stopped writing. Throughout the 1930s, she dabbled in a number of esoteric pursuits, sometimes as a dilettante, sometimes as a serious student. For a while in the late ’30s she was engaged to the aviation and automotive industrialist Vincent Bendix, 31 years her senior.

In 1936, Carman and her mother collaborated on a musical play curiously titled Gentlemen, the Queel!, which was never produced. Mother Diantha died in 1939, age 50. She and Carman had always been a matched pair; neither Carman’s biological father, James Hunter Neal, nor either of her stepfathers — Wellington Barnes, who died when Carman was 15, and George Pullen Jackson, who lived until 1953 — seem ever to have been a major presence in her life.

Neither, evidently, was her husband, Hamilton Fish Armstrong. A scion of the politically influential Fish family, Armstrong was a founding editor of Foreign Affairs, the journal of the Council on Foreign Relations. He and Carman married in 1945, when he was 52 and Carman was 32 — like Bendix, old enough to be the father Carman never had. They collaborated on a play, The Passionate Victorian, about the British actress Fanny Kemble, which (like Gentlemen, the Queel!) was never produced. The couple separated in 1949 and divorced in 1951.

Neither, evidently, was her husband, Hamilton Fish Armstrong. A scion of the politically influential Fish family, Armstrong was a founding editor of Foreign Affairs, the journal of the Council on Foreign Relations. He and Carman married in 1945, when he was 52 and Carman was 32 — like Bendix, old enough to be the father Carman never had. They collaborated on a play, The Passionate Victorian, about the British actress Fanny Kemble, which (like Gentlemen, the Queel!) was never produced. The couple separated in 1949 and divorced in 1951.

All through the 1940s Carman was a voluminous and tireless correspondent on all the eclectic and esoteric topics that interested her. Her papers at the University of Rochester are stuffed with letters to and from such personages as conductor Leopold Stokowski, literary editor Maxwell Perkins, stage designer Norman Bel Geddes, actress Estelle Winwood, Natacha Rambova (Rudolph Valentino’s ex-wife), and her old school chums Clara Jackson Martin and Mary Jackson St. John.

After ten years of publishers’ rejections of various works — and those unproduced plays written with her mother and husband — Carman’s fifth and final novel, Time Lay Asleep, was published by Harper & Bros. in 1946. It was a densely stylish but rambling and all-but-plotless tale of a family of Tennessee women raised by their soft-spoken but autocratic mother to need men even as they despise them; in their individual ways, all of them achieve unhappiness. Carman continued to write — especially letters — but she never published another word.

Photo courtesy Carman Barnes Papers

Back in those early heady days in Hollywood, Carman had told interviewers of her urge to travel (“I’d love to see Europe.”), and her intention one day to marry and have children (“I wouldn’t miss that experience for anything.”). Alas, that experience — motherhood, that is — was denied to her. And four years with Hamilton Armstrong seems to have provided enough marriage to last the rest of her life.

But the traveling — that urge, she was able to indulge. She left America in 1949, returning in 1951 only long enough to finalize her divorce from Armstrong, then sailing back to lead an expatriate’s life in Salzburg, Austria. Here she is in an undated photo, probably from about 1955, relaxing on the sundeck of the Tennerhof Hotel in Kitzbühel, Austria with her friends Mary Nelson (left) and Therese Bogdanowicz (center).

I’m sorry to have to report that Carman’s last decades appear to have been, on balance, less happy than she appears in this picture. Her biographical sketch on the Web site of the University of Rochester’s River Campus Libraries tells us that in the summer of 1952 she suffered “the first of several breakdowns”, and was treated with “insulin shock therapy and psychotherapy, among other methods.” She never returned to the U.S. and died at 67 on August 19, 1980 in Salzburg, where she is buried.

That biographical sketch also reports that in later years, speaking of her months in Hollywood, “she would tell interviewers that she was never given any writing work to do and that while she was photographed ‘700 times in the first week’, she was never given the opportunity to act in a film.” The fan magazines and trade publications of 1931 and ’32 tend to confirm what she said about those 700 photographs, but it seems to me they belie her assertion about never getting a chance to act. She certainly glossed over the episode of The Road to Reno. Maybe getting canned from that picture bothered her more that she wanted to let on, then or later.

And I’m not entirely convinced, either, that her stint as a Paramount writer came to nothing. Confessions of a Co-ed strikes me as having too many intersecting points with Carman’s various announced-but-never-made projects — to say nothing of Schoolgirl, novel and play — to be purely coincidental. And there’s the curious fact of Confessions going out without any writer’s credit at all. If Carman didn’t write it, who did? Ah well, not that it matters — nobody, even in 1931, seemed inclined to brag about that one. No doubt Sylvia Sidney and Phillips Holmes wished their names weren’t on it.

If that was the way Carman remembered it…well, she was there and I wasn’t, and everybody is past asking about it now. Anyhow, I choose to close this series with the picture that opened it. This is the way I like to think of Carman — pensive, placid, expectant, and very pretty. It’s this photo that makes me wish we had something, even one movie, to give us some idea of why so many people, for a while, took it for granted that she was headed straight to the top.

* * *

POSTSCRIPT: I mentioned this in the acknowledgments at the beginning of these posts, but now, at the end, I want to express once again my gratitude to Andrea Reithmayr, curator of the Carman Barnes Papers in the Department of Rare Books, Special Collections and Preservation at the University of Rochester’s River Campus Libraries. Andrea was always prompt and patient with my inquiries, and generous in providing documents and photographs from Carman’s life and career (the Libraries purchased Carman’s papers from Clara Martin, Carman’s lifelong friend and heir). “I am always glad when Carman gets some attention,” Andrea wrote me. I hope this attention has pleased her.

Five-Minute Movie Star: Carman Barnes in Hollywood, Part 3

All through May and June 1931 the fan magazines kept up their steady stream of items about Carman Barnes and how she was taking Hollywood by storm. Paramount’s ads continued to list her among “These Great Personalities” and “Stars That Draw!” alongside such names as Marlene Dietrich, Maurice Chevalier, Fredric March, Harold Lloyd and Claudette Colbert. Strangers and Lovers was still one of “These Mighty Productions” coming soon, touted in the same breath with Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Love Me Tonight, The Smiling Lieutenant and A Farewell to Arms. Readers of Screenland, Modern Screen and Photoplay were exhorted to write to her (at the studio, of course, 5451 Marathon Street, not her DeMille Drive digs) — even though none of those readers had set eyes on her unless they’d seen the pictures the magazines kept publishing.

All through May and June 1931 the fan magazines kept up their steady stream of items about Carman Barnes and how she was taking Hollywood by storm. Paramount’s ads continued to list her among “These Great Personalities” and “Stars That Draw!” alongside such names as Marlene Dietrich, Maurice Chevalier, Fredric March, Harold Lloyd and Claudette Colbert. Strangers and Lovers was still one of “These Mighty Productions” coming soon, touted in the same breath with Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Love Me Tonight, The Smiling Lieutenant and A Farewell to Arms. Readers of Screenland, Modern Screen and Photoplay were exhorted to write to her (at the studio, of course, 5451 Marathon Street, not her DeMille Drive digs) — even though none of those readers had set eyes on her unless they’d seen the pictures the magazines kept publishing.

Carman’s versatility as writer and actress continued to be a major talking point. Screenland’s “Screen News” column fairly gushed:

“A girl who looks lovely, acts well, sings, plays an instrument, can do either comedy or tragedy, is a good dancer — and is also capable of writing her own scenario a la this new little Carman Barnes, is bound to crow over less accomplished souls.”

The first tiny bubbles of doubt, however, were beginning to burble up here and there. The June Motion Picture published “An Open Letter to Mr. Paramount” by staff writer Frank Lee Dunne, wondering what was up at the studio. Beginning with the perennial question “What’s happening with Clara Bow?”, Dunne wrote:

Once I caught myself absent-mindedly penning [Clara’s] name on the fly-leaf of a book I was reading. The book was ‘School Girl,’ a most erudite exposé of school children, written by Carman Barnes, who, I understand, is also going to do big things for ‘dear old Paramount,’ as Jack Oakie says…Of course, it’s sorta funny, the announcement that Carman Barnes is being groomed for stardom. Writing an off-color book in schoolgirl style is no preparation for stardom.”

A reader combing the trades and fan mags for news of Paramount’s newest could be forgiven for getting confused over the titles being bandied about. Some were still talking about Debutante (with or without Confessions of) even as Paramount’s ads were ballyhooing Strangers and Lovers. Meanwhile, an item in Motion Picture Herald’s “Productions in Work” column on June 27 carried a bit more of the ring of authority. It announced yet a new title, The Road to Reno, as “Starting”. Only the names of Carman, Charles Rogers, Lilyan Tashman and director Richard Wallace suggested that this was the latest (and presumably final) incarnation of (Confessions of a) Debutante/Strangers and Lovers. Ominously, the author of The Road to Reno‘s original screenplay was listed as Virginia Kellogg, not Carman. (Kellogg was a 23-year-old newbie just starting out; her career would be spotty, her credits few and far between, but she would in time snag a couple of Oscar nominations, for White Heat with James Cagney in 1949 and Caged with Eleanor Parker the following year.)

Over in the pages of the July Photoplay, Cal York (“The Monthly Broadcast of Hollywood Goings-On!”) hadn’t yet got the memo about the new title, but he had some juicy details:

“Carman Barnes wrote ‘School Girl.’ She is under age. She was considered a genius.

“Someone in the East saw her and decided she was Movie material. They signed her at $1,000 a week now; $1,250 a week in a few months; and $5,000 a week at the end of three years — provided the options are taken up.

“First, she was to star in her own writings. ‘With and By Carman Barnes.’ A good thought, but when they came to adapt her story, this was discarded.

“Then she was to play the part of a Southern debutante.

“Well, she’s finally playing the rôle of a tattered gal of the South — sort of a white trash interpretation in ‘Strangers and Lovers.’

“And here’s the funny side. Eight weeks are allowed on the production schedule on a not-too-big picture. When three weeks is a long shooting schedule for pictures in this day of hurry-up talkies.

“And the eight weeks are to provide ample time for proper photography. The girl’s lines need much camera attention.

“She has one lucky break.

“Tom Douglas of stage fame has been cast opposite her.

“He can teach her much — and we understand he is willing and so is she!”

So Paramount was scheduling extra time to coax the new kid along, eh? Interesting.

And by the way, what do you suppose York meant by the coy insinuation in that last line about Carman and Tom Douglas, the co-star she found “charming, very humorous…southern and from a good family”? In her April letter, Carman also told Clara Jackson that he was “not a ‘pretty’ movie actor.” Could that have been code for saying that Douglas was definitely heterosexual? Well, let’s let it pass — Carman, Tom Douglas and Cal York are all past asking about it now.

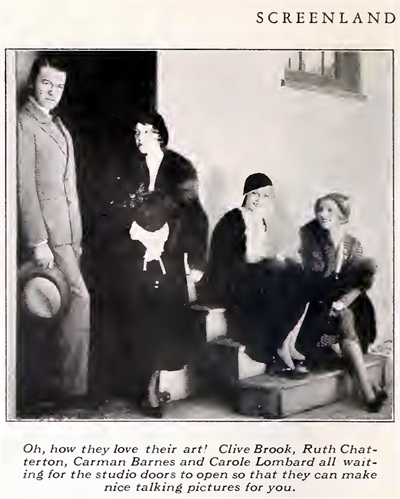

In the next issue of Motion Picture Herald (July 4), The Road to Reno was listed as “Shooting” — and sure enough, here’s a publicity still from the July Screenland (“Oh, how they love their art!”) showing Clive Brook, Ruth Chatterton, Carman and Carole Lombard loitering on the Paramount lot waiting for the cameras to roll on their respective pictures. The photo is posed, no doubt, but at least it offers photographic evidence that Carman was reporting to the set.

In the next issue of Motion Picture Herald (July 4), The Road to Reno was listed as “Shooting” — and sure enough, here’s a publicity still from the July Screenland (“Oh, how they love their art!”) showing Clive Brook, Ruth Chatterton, Carman and Carole Lombard loitering on the Paramount lot waiting for the cameras to roll on their respective pictures. The photo is posed, no doubt, but at least it offers photographic evidence that Carman was reporting to the set.

In that same issue, Screenland’s editor Delight Evans, boasting of the magazine’s prescience in choosing future stars, wrote, “But meanwhile watch the youngsters like Carman Barnes and Sidney Fox and Sylvia Sidney and Evalyn Knapp — we picked them too.” (We’ve already seen what became of Sidney Fox and Sylvia Sidney. For the record, Evalyn Knapp fell somewhere in between: serials, B westerns — she played Lou Gehrig’s sister in one for fly-by-nighter Sol Lesser in 1938 — and uncredited bits. Her career petered out in 1943 and she retired to marriage and family life, dying in 1981 at 72. So much for Delight Evans’s powers of prognostication.)

Motion Picture Herald continued to report The Road to Reno as “Shooting” on July 11 and 18; then in the July 25 issue the picture’s release date was announced as September 26. One week later, on August 1, The Road to Reno — still starring Charles Rogers, Carman Barnes and Lilyan Tashman — was marked “Completed”.

At this point things get a little murky, complicated by different publications’ diverse press deadlines. For example, in the August issue of Modern Screen (published in mid-July), its “Modern Screen Directory (Players)” had the following listing:

“Barnes, Carman: unmarried; born in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Write her at Paramount studio. Contract star. To make her talkie debut in ‘Confessions of a Débutante.'”

Way behind the curve.

Meanwhile, in the same issue of Motion Picture Herald (August 1) that announced The Road to Reno as completed, the following appeared in the Herald’s “On the Dotted Line” column:

“…Lilyan Tashman, Charles ‘Buddy’ Rogers, Peggy Shannon, William Boyd, Irving Pichel, Emil Chautard, Anderson Lawler, Caryl Lincoln in ‘The Road to Reno’…”

It was an ominous sign for any Carman Barnes fans who might have been paying attention; in fact, Peggy Shannon — who had already replaced Clara Bow in The Secret Call earlier in the year — had now replaced Carman. The Road to Reno was still scheduled for release on September 26, so reshoots were no doubt in progress, making the Herald’s “Completed” stamp a bit behind the curve, albeit not as far behind as Modern Screen.

Not as far behind as Motion Picture magazine either. In their September issue (published mid-August), under “What the Stars Are Doing and Where They May Be Found”, Carman is described as “playing in The Road to Reno — Paramount Studios, 5451 Marathon St., Hollywood, Cal.” But by that time, the following item had appeared in Motion Picture Daily’s August 28 “Off the Record” column (the reporter, fittingly enough, is anonymous):

“As mystifying as any of Hollywood’s mysteries, the story of Carman Barnes. Picked and touted by Jesse Lasky as a find, Miss Barnes was subjected to a nation-wide publicity campaign a la Paramount’s best. The excitement even extended into trade paper advertising.

“Then the Hollywood understroke came into play. Miss Barnes cooled her heels on the Marathon Avenue lot for months until the other day she walked off the lot, through with Paramount and nary a picture to her credit.”

There’s no telling what “the other day” from August 28 was, but this is the first mention in print that Carman and Paramount had come to a parting of the ways, barely seven months into her long-term contract. Motion Picture Daily presented it as Carman’s idea, but other publications told a different story, albeit weeks and even months later. In the meantime, gossip column items continued to drop her name (Motion Picture, September: “Carman Barnes reports that to date no one has tried to call her ‘Car’ Barnes.”), and readers were still being told they could write Carman in care of Paramount’s Marathon Street studios. But by October the news was finally sinking in.

As usual, Cal York was Johnny-on-the-spot in the September Photoplay (which may have actually hit the stands before that Motion Picture Daily item):

“The story of Carman Barnes is one of those things that could only happen in Hollywood. Maybe you remember that Carman is the youthful authoress who wrote the sensational novel ‘School Girl’ and if school girls had acted like that in Old Cal’s day, they would have been spanked and sent to bed without their supper. Instead the authoress was signed under contract to Paramount to write her own stories and play the starring rôles in them.

“The executives raved about her — never, so the press was told, did a girl have so much of what it takes.

“The publicity department was told to give Carman a big sendoff.

“She was photographed from every angle — well, almost. She was interviewed and kowtowed to and flattered.

“Various announcements of her screen rôles were announcements, merely. She was assigned to ‘Road to Reno,’ but Peggy Shannon was substituted, and even her own play, ‘Debutante,’ was put aside for lack of a story. Now, it seems, Paramount will not renew her contract. And she’s never appeared in a single picture nor written a line that has reached the screen!

“Well, she drew her weekly paycheck and the publicity department was kept busy for a spell.”

It’s amusing now, 86 years down the line, to see how schizophrenic some of Carman’s fan magazine coverage was becoming by this time. The October issue of Motion Picture is a case in point. Carman gets four plugs in all. One of them, in the magazine’s regular “The Hollywood Circus” feature, mentions how dinner party hostesses around town, including Carman, were having trouble catering to the finicky palate of Paul Lukas. It’s standard puff-stuff, a good way for studio publicity departments to keep their contract players’ names in print (whether Carman ever actually threw a dinner party and invited Paul Lukas is an open question).

It’s amusing now, 86 years down the line, to see how schizophrenic some of Carman’s fan magazine coverage was becoming by this time. The October issue of Motion Picture is a case in point. Carman gets four plugs in all. One of them, in the magazine’s regular “The Hollywood Circus” feature, mentions how dinner party hostesses around town, including Carman, were having trouble catering to the finicky palate of Paul Lukas. It’s standard puff-stuff, a good way for studio publicity departments to keep their contract players’ names in print (whether Carman ever actually threw a dinner party and invited Paul Lukas is an open question).

But the others are more pointed, and surely didn’t come from the boys at Paramount. In “News and Gossip of the Studios” there was this:

“CARMAN BARNES is going to write a novel of Hollywood. Let’s hope it is not based on her own experiences in the movies. There will be too many blank pages — where nothing happens.”

Ouch! Later in the same column, just in case readers weren’t in on the joke, the magazine explained it:

“CARMAN BARNES — whom Variety refers to as ‘Paramount’s by-and-with girl’ — will soon be Paramount’s ‘by-with-and-out girl.’ The studio has admitted she will probably never make a foot of film, though she has been technically billed as a star for months. The pictures printed of Carman seem to reveal a rather odd screen personality, but a photographer tells me they are the few chosen from literally hundreds of portraits of the young authoress taken.”

Now this was a low blow. The reporter knew perfectly well that the studios always took “literally hundreds” of pictures of their contract players — stars like Garbo who could sit for half a dozen shots, every one pure gold, were rare.

Even worse than these, perhaps, was the issue’s very first (p. 14) mention of Carman, in “Your Gossip Test (Hollywood Knows The Answers To These Questions — Do You?)” by Marion Martone. Question no. 10:

“Who is the girl who has been publicized as a forthcoming screen star and has been cast in several pictures and yet has not been seen on the screen so far?”

And the answer, on p. 96:

“Evidently the screen camera has been unkind to Carman Barnes, who is the author of ‘School Girl,’ because she has been assigned to several pictures and then taken out of the cast.”

“Several pictures”? Well, there were certainly several titles bouncing around. Maybe that was what Marion Martone meant.

The snark had started even before that, though. One anecdote got a couple of treatments that illustrate how “Hollywood’s Newest Genius” (Silver Screen, May ’31) was fast morphing into a figure of scorn. From Modern Screen’s “Film Gossip of the Month” for September, just as the news of Carman’s retreat was getting around:

“Blasé Hollywood had a good laugh the other day. Although Carman Barnes hasn’t done any work as yet she’s been receiving her weekly paycheck from Paramount — and the checks are four-figured, too. So it was only natural that when Carman waltzed into her manager’s office and asked when her vacation started the poor man was too flabbergasted to answer.”

Early profiles of Carman had made a point of mentioning her lively sense of humor. This (if it really happened) sounds to me like a joke on Carman’s part that Modern Screen’s gossipmonger deliberately chose to take the wrong way. But the same story got an even nastier twist two months later in The New Movie Magazine. In an article entitled “Hollywood Needs a Good Scandal”, writer Herb Howe went out of his way to get his digs in, even though the subject at hand was Hollywood’s drive to cut costs in the face of the deepening Depression:

“With the Wall Street bankers moving into Hollywood there has been a move to economize. Supervisors are now allowed only four relatives on the pay-roll. But this miser policy didn’t affect Carman Barnes. She was on the Paramount pay-roll for six months without doing a part. When finally a bit was found for her she screamed: ‘But when do I get a vacation?'”

And elsewhere in that same November issue:

“Paramount has finally settled with Carman Barnes for a cash consideration for the balance of her contract, which had six more months to go. Miss Barnes was discovered by Jesse L. Lasky in New York, after he was attracted to her ability as the author of a sensational book on boarding-school life. She was later sent to Hollywood where the studio applied every trick known in photography to bring out that certain screen magnetism so necessary to establish popularity, but the young girl would not respond to that mysterious element of camera lens with the result that Paramount decided it was cheaper to relieve themselves of the charge by making a cash settlement.

“Meanwhile, Miss Barnes is said to be writing a novel about Hollywood in which, rumor has it, she’ll tell tales.”

It’s too much to hope for that any of Carman’s scenes from The Road to Reno — much less any screen tests she may have made — have survived in the Paramount vaults. But wouldn’t it be enlightening to troll through the files for memos documenting some of the “trick[s] known in photography” that Paramount deployed to get her to “respond to that mysterious element of camera lens”? Ah well, maybe someday…

In any case, by Autumn 1931 Carman Barnes was well and truly gone. No more horseback riding in Griffith Park, no more lolling on the beach, no more “primieres” or bad food at the Brown Derby.

And that novel Miss Barnes was said to be writing? We’ll get to that, and other things, when we return.

Next time: Hollywood after Carman — and vice versa

Speak of the Devil…

I interrupt my survey of the Hollywood career of Carman Barnes for an announcement of urgent importance to movie buffs everywhere, and to fans of film noir, Ray Milland, and director John Farrow in particular:

I interrupt my survey of the Hollywood career of Carman Barnes for an announcement of urgent importance to movie buffs everywhere, and to fans of film noir, Ray Milland, and director John Farrow in particular:

Alias Nick Beal is returning!

If the title means nothing to you, then you have not read my 2011 post on this unsung masterpiece. You can find it by scrolling down the index column on the right to “Lost and Found: Alias Nick Beal“ — or by clicking on the link you just read. Go ahead, I’ll wait.

To be fair, while Alias Nick Beal is a masterpiece, it’s not entirely unsung. The late film historian Leslie Halliwell was a fan, having caught it almost by accident during its half-hearted 1950 release in Great Britain (where it was titled The Contact Man). Otherwise, the movie died unnoticed in 1949 and has been virtually forgotten ever since. Long a staple of Late Late Shows on local TV stations (where I discovered it in the 1960s), it was last shown publicly, to the best of my knowledge, on The Movie Channel in 1990.

That will change this coming Wednesday, August 2, 2017. Turner Classic Movies will screen Alias Nick Beal at 9:00 p.m. Pacific Time — that is, at 12:00 Midnight Eastern Time, in the earliest hours of August 3. A most appropriate time slot for this creepy, deeply sinister political melodrama.

A word to the wise is sufficient. Don’t miss Alias Nick Beal. After it’s over…well, pleasant dreams.

Five-Minute Movie Star: Carman Barnes in Hollywood, Part 2

Like her Schoolgirl heroine Naomi Bradshaw, Carman Barnes shared a suite at boarding school with two sisters, Clara and Mary Jackson. And in Carman’s case, she remained close to the Jackson girls for the rest of her life. In April 1931, Carman wrote a letter to Clara Jackson that survives in her papers at the University of Rochester. I quote it here in its entirety, with Carman’s occasional misspellings left intact:

Dearest Clara,

Dearest Clara,

No, Miss Barnes is not temperamental, glamorous or mysterious as yet. And she actually doesn’t bite. And Carman would love to have the two little Jackson girls come to visit her in the sad little town of Hollywood, if she doesn’t take that little actress away on location. You see, Miss Barnes’ first picture may be made in Florida, but even if it isn’t, Carman would be a dull hostess having to put the blonde star to bed every night at eight o’clock, tucking her in between the ermine lined sheets and smelling her breath to be sure she hasn’t sneaked a high ball. Miss Barnes will tell you that it’s no cinch being a movie star. However we’ll see how things work out, and how much breathing space she’ll get between pictures. Old writer Carman is sailing for Europe in July–believe it or not–which you probably don’t by now.

The screen’s newest siren—who kisses—and wonders if her chin’s at the right angle (before the camera)–doesn’t attend many Hollywood parties, so it might be dull for the little Jacksons. Hollywood parties are—Hollywood parties. Very ginny, and very disillusioning. The last one Miss Barnes went to, an important studio executive engaged in a little battle on the floor with an important Broadway playwright–with much rolling gnashing of teeth, blackening of eyes, and —it is said shamefully—biting! All the sweet young thing’s were there too, Mary Brian, Janet Gaynor, Frances Dee, Philips Holmes, Betty Davis— and you know, they are very, very nice. So is Carman Barnes. She went home very ill, and it took the young thing two days to recover. But honestly, I can’t stand that sort of thing, and it happens so often and so easily here. It would be bad if it ever reached the newspapers, too. Hollywood is nutty over gossip–at any cost.

When the young actress isn’t working, I loll on the beach, ride horseback three or four times a week. A young English boy and I ride early Sunday mornings, way up in the hills. We gallop up, swing around overhanging cliffs, almost leap off into the air, swerve, brandish our sticks, and shriek: “We have met the enemy in the passes and he is ours!” Try it some time. It’s great sport. I have a nice tan, too, and am very healthy.

After you’ve once “been places” in Hollywood, there’s no reason to go again. Everything is of a sameness, the people are the same, movie people, they talk about the same things, movies, they eat the same thing, movies, and they drink the same thing, movies. Everyone likes to go to the Brown Derby once–but after a few times, it’s nothing but a small town café with hard seats and bad food. Primieres are fun—once, and sort of amazing, too, with thousands of people lining the side walks, great fires burning in the streets, carpets, canopies, flowers, radio announcers, ermine coats, stars swamped with orchids, glaring arc lights, and the “herd” yelling for autographs. But after one–they’re all alike, maybe the lights are bigger, the fires brighter–for one star than for another, but that’s all. Now, have I disillusioned you in your glorified conception of Hollywood. You might like it, I don’t know. There are so few people here worth knowing, so few who have any back ground, any culture, any intelligence, any humor.

I go out with very few people. Tom Douglas, for one, the boy who is to play with me in my picture. He is charming, very humorous. He is southern and from a good family. That can’t be said of many people out here. And more than anything, he is not a ham, nor a “pretty” movie actor. I go out with a young producer and a young scenario writer, and Jack Spurlock, a boy from home who came out with us. That’s practically all. You’d be surprised how quiet the lives are that most people lead in Hollywood. Did you know that the streets were deserted by twelve o’clock?

I’ll send you a picture, if I ever get time to mail it off. And write to me, you scamp— I still love you loads, darling-

Carman

As I said before, the kid could write.

By February 1931 Paramount was spreading the word of their new discovery. The studio sent a letter to all their theater managers — and Paramount had the largest theater chain in the country — introducing Carman and telling them (according to Variety) “how glad she is to be a picture star as well as a writer.” For good measure, managers were offered an autographed picture of Miss Barnes. It would be interesting to know if any managers took Paramount up on the offer, and if any of the photos survive. (At about this same time, reports began to circulate that Paramount had also paid Carman $30,000 for the screen rights to Schoolgirl. Whether because of the novel’s subject matter or the play’s lukewarm reception on Broadway, nothing ever came of that, and the idea was soon dropped even by the gossips.)

By February 1931 Paramount was spreading the word of their new discovery. The studio sent a letter to all their theater managers — and Paramount had the largest theater chain in the country — introducing Carman and telling them (according to Variety) “how glad she is to be a picture star as well as a writer.” For good measure, managers were offered an autographed picture of Miss Barnes. It would be interesting to know if any managers took Paramount up on the offer, and if any of the photos survive. (At about this same time, reports began to circulate that Paramount had also paid Carman $30,000 for the screen rights to Schoolgirl. Whether because of the novel’s subject matter or the play’s lukewarm reception on Broadway, nothing ever came of that, and the idea was soon dropped even by the gossips.)

The seeds planted with the fan mags in January began bearing fruit in April. In Photoplay, gossip columnist Cal York’s “Monthly Broadcast of Hollywood Goings-On!” trumpeted, “Girl novelist turns actress!”:

Hollywood’s newest Cinderella is Carman Dee Barnes, eighteen-year old writer who ground out a story called “Schoolgirl” when she was fifteen.

Last fall she went west for Paramount to write. Now she’s to play the leading role in a story written by herself.

She’s reported to have said that she’s a little shy of pictures because she has to write down to her audiences!

This, from a kid writer of frenzied flapper fiction.

Are we allowed a small chuckle, or a modest guffaw? Sure!

That same month — April 18, to be precise — an ad in Motion Picture Herald listed Carman among Paramount’s “Screen Luminaries”, already placing her in such company as Harold Lloyd, Marlene Dietrich, the Marx Brothers, Maurice Chevalier — and yes, Clara Bow. Her first picture — the one that in January interviewers had heard about as Debutante or A Debutante Confesses or Confessions of a Debutante — had undergone a change of title, which would be the source of some confusion when those interviews finally saw print in May and June. Now, according to Paramount, the picture was Strangers and Lovers, “featuring Carman Barnes and Tom Douglas. Directed by Richard Wallace. A tale of a girl who is afraid she is wicked.”

In May, along with profiles and prominent plugs in Screenland and Silver Screen, Carman scored an item in Picture Play’s “Hollywood Highlights” column by Edwin and Elza Schallert that paid tribute to her skill at the age-old southern belle tease:

In May, along with profiles and prominent plugs in Screenland and Silver Screen, Carman scored an item in Picture Play’s “Hollywood Highlights” column by Edwin and Elza Schallert that paid tribute to her skill at the age-old southern belle tease:

What chance will a girl in her teens now have to impress a movie producer, unless 1. She has tossed off a couple of novels? 2. She has gifts as a sculptor, playwright and musician? 3. Possesses a flair for snappy and sophisticated conversation? 4. Is — in a word — just a whirlwind of intellectuality?

Carman Barnes, eighteen-year-old Paramount discovery, sets a standard that must be wretchedly depressing to any young seeker of celluloid honors. For she has a veritable galaxy of smart attributes, including those above enumerated.

And what a free, informal soul this young maid of movieland is, incidentally! Our first glimpse of Carman was on a breezy day in the broad open spaces of the studio, clad in a futuristic-looking bath robe, and gayly diverting an audience of three wise old scenario writers with her piquant repartee. Carman was waiting photographic test time, and if the breezes blew lightly on her loose-fitting outer garment, she should worry. Persiflage and the laughter took complete precendence over the day’s chilliness or the wind’s revealing whimsies with a lady’s boudoir habiliments.

An insouciante, charming, and distinctly clever young woman from the Southland is this precocious author of “School Girl” and “Beau Lover,” who is to appear in her own story, “Débutante.” Amazing as it may seem, she sometimes photographs not unlike Garbo.

(As a side note, Mr. and Mrs. Schallert in those days had an eight-year-old son, Billy, who would grow up to be one of the most prolific actors in Hollywood history, playing — among hundreds of other roles — Dobie Gillis’s English teacher, Patty Duke’s father, and Milton the Toaster for Kellogg’s Pop-Tarts. William Schallert left us last year at the age of 93.)

The change from (Confessions of a) Debutante (Confesses) to Strangers and Lovers became official in an ad Paramount placed in the May 13 issue of Variety: “Debut of a new blonde beauty who will bowl screendom over — Carman Barnes. In a big cast with Charles Rogers, Lilyan Tashman and others of established drawing power. In a strong story of young love that will long be remembered.” So this was the fulfillment of Variety’s February 11 item — two veterans, Charles “Buddy” Rogers and Lilyan Tashman (not to mention “others of established drawing power”), were coming aboard to do some of the heavy lifting for Carman and her “co-star” Tom Douglas. And in case you’ve lost track, in less than a month the story has gone from “a tale of a girl who is afraid she is wicked” to an “absorbing drama of an innocent-wise 19-year [old] charmer in a barracks town” to “a strong story of young love that will be long remembered.” An observant reader might have thought that somebody at Paramount was having trouble remembering that story for very long — might indeed have wondered if there was a story at all.

The change from (Confessions of a) Debutante (Confesses) to Strangers and Lovers became official in an ad Paramount placed in the May 13 issue of Variety: “Debut of a new blonde beauty who will bowl screendom over — Carman Barnes. In a big cast with Charles Rogers, Lilyan Tashman and others of established drawing power. In a strong story of young love that will long be remembered.” So this was the fulfillment of Variety’s February 11 item — two veterans, Charles “Buddy” Rogers and Lilyan Tashman (not to mention “others of established drawing power”), were coming aboard to do some of the heavy lifting for Carman and her “co-star” Tom Douglas. And in case you’ve lost track, in less than a month the story has gone from “a tale of a girl who is afraid she is wicked” to an “absorbing drama of an innocent-wise 19-year [old] charmer in a barracks town” to “a strong story of young love that will be long remembered.” An observant reader might have thought that somebody at Paramount was having trouble remembering that story for very long — might indeed have wondered if there was a story at all.

In May and June the gossip columns were liberally salted with items keeping Carman’s name front and center. Gladys Hall in Motion Picture and Cal York in Photoplay mentioned how Schoolgirl had gotten her “expelled from” (York) or “asked to leave” (Hall) her tony New York prep school. Meanwhile, Edward Churchill in Silver Screen asserted that she did manage to graduate from Ward Belmont in Nashville (the school she was attending when she wrote that first novel) “just after her seventeenth birthday.”

An item in the June Motion Picture mentioned Carman gushing over “a star famous for her vamp roles” (Who?, I wonder; Mae Murray? Nita Naldi? Louise Brooks? Theda Bara?), and clasping her hands in admiration of the lady’s orchid corsage: “Ah! how I adore orchids! I wish I could wear them — but I’m too young!”

Perhaps most amusing of all, Picture Play’s New York correspondent, Karen Hollis, went trolling among the bellhops at Carman’s former hotel:

Is She an Actress? The announcement that Carman Barnes, the child prodigy author, was also to act for Paramount fell like a bombshell in the New York hotel where she used to live. It happens that I live there now, and all the bell boys think I ought to know her just because I, too, have a typewriter.

They say she is an awfully smart kid, “Smart enough to act dumb and wistful and helpless when there is something she wants.” “Act? I should say she can. She was acting all the time, especially around the lobby and library when a flock of college boys blew in for the week-end.”

“Beautiful? Well, she’s no Claudette Colbert, but she’s pert and cute. She’ll be all right if people don’t make too much fuss over her. She loves attention. Her mother should have spanked her and torn up that dirty book she wrote.”

Reading that item, Carman the mature-beyond-her-years phenomenon suddenly sounds 18 again. Or rather, 17 — the age at which those New York bellhops knew her (and no doubt eagerly devoured “that dirty book she wrote”).

In that same June issue of Picture Play, Edwin and Elza Schallert in “Hollywood Highlights” commiserated with Carman for having “to sign her movie contract in the presence of a judge, because she happens to be a minor!…Movie companies arrange to have contracts with minors signed this way so that they may not be broken on the grounds of youthful incompetency of the player in business matters.” But this was old news by June: that hearing had happened way back in March. Still, it was publicity, and it lent the juggernaut of Carman’s approaching stardom the imprimatur of the California State Superior Court.

Anyhow, the days of magazine profiles, ballyhooing ads and gossip-column plugs, of Carman’s partying and horseback riding and enduring the hard seats and bad food of the Brown Derby, were reaching a climax — Carman was finally going before the cameras.