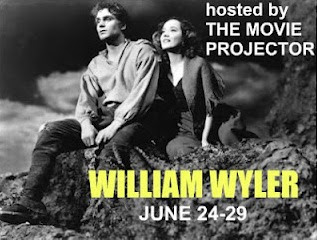

July 1 will mark the 110th anniversary of the birth of William Wyler (1902-81), peerless movie director par excellence. The occasion is being observed by a blogathon hosted by The Movie Projector over the next six days, in which many of my fellow members in the Classic Movie Blog Association (CMBA) will be holding forth on their favorite Wyler pictures. Go here for a list of blogathon participants and links to their individual posts as they go up.

For my part, in conjunction with The Movie Projector’s blogathon, I’m republishing a series of five posts I did on Wyler in 2010, one a day for five of the six days of the blogathon. Happy Birthday, Willy, and thanks for the memories!

* * *

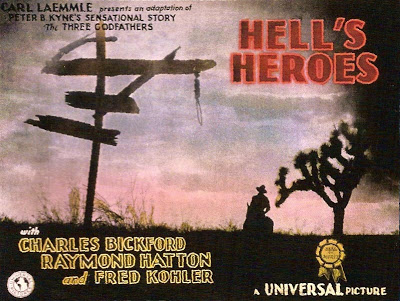

In his biography of William Wyler, A Talent for Trouble, author Jan Herman makes the kind of statement movie buffs love to see become obsolete: “There are no extant prints of the sound version of Hell’s Heroes.” Herman then goes on to discuss Wyler’s first talkie in terms of its silent version (like many early sound pictures, Hell’s Heroes was released silent as well, for theaters that had not yet been wired for sound).

A Talent for Trouble was published seventeen years ago, and I’m sure Herman himself is pleased to know that his pronouncement is no longer operative. Fortunately for us, Hell’s Heroes was remade by MGM in 1936 under author Peter B. Kyne’s original title Three Godfathers (and again in 1948 as 3 Godfathers, that time directed by John Ford and starring Duke Wayne), so ownership of this Universal picture devolved upon Metro.

In those days, when Metro remade a movie, it was studio practice to buy up and suppress (some say destroy) any earlier versions. If those originals were in fact earmarked for the incinerator, we probably have a fumbling studio bureaucracy to thank for the fact that we can still see Paramount’s 1932 Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Universal’s 1936 Show Boat, the British Gaslight of 1940, even MGM’s own silent Ben-Hur, and other movies that the suits at the Tiffany Studio took it into their heads to remount over the years.

We can certainly thank MGM’s acquisitiveness for the fact that these titles from other studios ended up in the MGM library and are now owned by Warner Home Video. The Warner Archive offers a double-feature package of Hell’s Heroes with MGM’s 1936 remake, and it affords us an opportunity to appreciate this landmark in William Wyler’s career that wasn’t available to Jan Herman in 1995.

Peter B. Kyne’s short novel The Three Godfathers was published in 1913 in The Saturday Evening Post, and was his first great success in a writing career that would carry him through 1940 as a popular and well-read author. The story has a mythic resonance: three outlaws on the run from their latest crime come across a dying woman in childbirth in the desert. Before the doomed mother dies she extracts a promise from the three desperadoes to take her baby to safety, and the helpless child awakens the latent humanity of the three unregenerate bad men.

By the time Carl Laemmle Jr. decided to make The Three Godfathers the basis of Universal’s first outdoor all-talkie, the studio had already gotten more than its money’s worth out of it. There was a screen version in 1916 starring Harry Carey, and another in 1919 titled Marked Men, again with Carey and this time directed by John Ford. Both pictures had been good moneymakers for Universal. (There was another Ford western in 1921, Action, which the IMDb claims was based on Kyne’s story, while Clive Hirschhorn’s The Universal Story gives an entirely different and unrelated plot. Alas, this is one of Ford’s many westerns presumed lost, so we may never resolve the discrepancy.)

To direct the new version of the story, Laemmle chose 27-year-old William Wyler. Wyler had begun work on the Universal City lot as an errand boy, and after a rocky start — at one point studio chief Irving Thalberg dubbed him “Worthless Willy” — Wyler had risen to where he was considered an asset to the studio. Hell’s Heroes was to be his first talkie, but he was no stranger to westerns, having cut his directorial teeth on them from 1925 on — first a series of nearly two dozen two-reel horse operas for Universal’s so-called “Mustang” unit, then five-reel features in the “Blue Streak” series.

Wyler began shooting in California’s Mojave Desert and Panamint Valley, just south of Death Valley, on August 9, 1929. Jan Herman tells us that the temperature on location rose as high as 110 degrees Fahrenheit, but those of us who know the California desert in August suspect that’s probably a conservative figure — 115 to 125 sounds more like it. In any case, one can only shudder at what the poor cameraman in his booth — like a meat locker, but without refrigeration — must have gone through. He must have needed five gallons of water a day just to ward off dehydration.

In the movie, the three outlaws — Charles Bickford, Raymond Hatton and Fred Kohler — are on the run after robbing the Bank of New Jerusalem on the edge of the desert (and killing the cashier, who we later learn was the father of the baby they rescue — a nice detail not in Kyne’s story, supplied by scenarist Tom Reed). For Wyler’s company, New Jerusalem was Bodie, Calif., an erstwhile Gold Rush boomtown near the California-Nevada border.

Bodie was near the tail-end of its boom-and-bust history in the late summer of 1929. Originally founded on a nearby gold strike in 1859, it had grown by 1880 to a reported population of 10,000, home to 65 saloons and other establishments of ill repute. By 1929 the population hovered around 100. Three years after the Hell’s Heroes crew left town, so the story goes, a young boy at a church social threw a tantrum when he was given Jell-O instead of ice cream. Sent home as a punishment, he set fire to his bed and burned down over 90 percent of the town. The final blow came in 1942, when War Production Board Order L-208 closed down all nonessential gold mines in the country, including Bodie’s; even the U.S. Post Office closed. Today, what’s left of Bodie is a California State Park and a National Historic Landmark.

Notwithstanding the efforts of that youthful Depression-Era pyromaniac, traces of Bodie as it appears in Hell’s Heroes survive to the present day. Here’s Bodie’s Methodist Church, which figures prominently in the movie’s opening and closing scenes, as it appears today.

And here it is again, on the left edge of the frame, at the top of Bodie’s — er, that is, New Jerusalem’s — dusty main street.

Here’s a glimpse of town and the hills beyond in the closing moments of the movie …

… and a similar view taken more recently, showing what’s left of the same street.

Hell’s Heroes was a success for Universal and for Wyler personally. He’d become an asset to Universal for his westerns, but outside the studio Universal’s westerns — cranked out in days for small-time houses in neighborhoods and farm towns — hardly deserved notice. Now people were noticing. Over at Warner Bros., Darryl F. Zanuck ordered all his producers to see “this picture by this new director.”

What specifically excited Zanuck was a tracking shot that Wyler inserted as a way to sidestep a conflict with his leading man, Charles Bickford (on the right in this picture; the others are Raymond Hatton, left, and Fred Kohler). Bickford was a recent import from Broadway — Heroes was his third picture, made and released hot on the heels of the other two — and he evidently didn’t cotton much to being directed by some Hollywood rube who didn’t know anything about real acting. Herman tells us he even went out of his way to undermine Wyler with his fellow actors, an unconscionable breach of protocol then, and an actionable offense under union rules now.

Their particular conflict came over a scene late in the movie as Bickford, the last survivor of the three bandits, trudges through the desert with the baby in his arms. Wyler wanted Bickford, carrying a rifle as well as the child, to first drop the butt-end of the rifle in the dust and drag it for a distance before dropping it altogether. Bickford refused. He insisted on stopping in his tracks, looking at the rifle, then hurling it away from him into the dirt.

I almost wish this shot survived in the Universal vaults; I’d love to see it, because it sounds perfectly ridiculous — just the kind of grandiloquent gesture you’d expect from a stage-trained ham with a lot to learn about movie acting. A man dying of thirst won’t be able to summon the strength to throw a heavy rifle at all — and besides, shooting the scene in a real desert, he’d have to throw it about a hundred yards before it looked as impressive to the camera as the actor doing it thought it did.

Wyler’s solution was ingeniously simple. He filmed the scene the way Bickford wanted to play it. Then, one day when Bickford wasn’t on call, he dressed a prop man in Bickford’s boots, had him make tracks in the desert sand, and photographed them with a moving camera.

First we see just the bandit’s footprints, occasionally staggering and shuffling…

…then the tracks and the divot dug by the rifle butt…

…then the discarded rifle itself…

…and so on through other items discarded by the bandit under the grueling desert sun. When we next see Bickford’s character, he’s stumbling along clutching the child, discarding the last of his burden — the gold from his bank robbery.

Bickford’s reaction to this end run is not recorded. He no doubt didn’t see it until the picture was finished. Did he recognize the tracking shot as a directorial tour de force and an improvement on his own idea? Maybe not; Bickford was always headstrong and cantankerous, and I suspect the whole thing rankled: when he next worked with Wyler — 28 years later, on The Big Country — they took up squabbling again as if they had never left off.

But it’s not as if Wyler ruined Bickford’s budding career. In fact, Hell’s Heroes is probably where he first gave evidence of the actor he’d become, and it’s still one of his best performances. Along with the four other movies he appeared in during 1930, this one marked him as a strong and distinctive actor who bore watching.

It marked Wyler as someone worth watching, too. Variety‘s review called it “gripping and real. Unusually well cast and directed.” True, the movie’s director was misidentified as “Wilbur Wylans” — but it was the last time anybody would make that mistake.

One who didn’t like Hell’s Heroes, it must be said, was Peter B. Kyne. Asked to provide a complimentary letter for studio publicity, he indignantly refused. “Frankly,” he wrote to Tom Reed, “I think your Mr. Wyler murdered our beautiful story … I don’t care how much money the picture makes, my conscience will not let me cheer for the atrocious murder of one of the few works of art I have ever turned out … I will not write any letter to Mr. Wyler. The young gentleman must fight his weary way through life without a helping hand from me.”

My, aren’t we cranky! Maybe Kyne was miffed that the movie altered the character dynamics, embellished the plot and changed the ending of his story. Whatever got him all riled up, there’s no getting around the fact — the man had rocks in his head. Hell’s Heroes is a terrific picture, and in 1930 everybody but him knew it. Of the three versions of the story I’ve seen, it is easily my favorite, and certainly the simplest and least sentimental.

The acting is straightforward and unpretentious, and at a swift, lean 68 minutes the movie spends no time wallowing. The presentation is hard-eyed and terse, which makes the three desperados’ conversion to decency and self-sacrifice all the more persuasive and moving. As the first of the bandits to die, Raymond Hatton has a line that’s straight out of Kyne’s story: “Don’t let my godson die between two thieves.” Hatton’s reading of the line, and the staging of his suicide as the other outlaws plod doggedly away, are presented with a simplicity that — in hands other than Hatton’s and Wyler’s — could easily have become lachrymose and bathetic.

There is a creative use of sound, too, that Jan Herman could not have appreciated in 1995, not having an extant print to review. Notice especially the last scene, as Bickford’s character staggers into that church, the in-and-out subjective sound, so eloquently showing us the man’s delirious condition.

Seen today, too, the movie’s age works for it. The primitive technology of early sound, the rugged conditions on location, the stark frontier setting and the primal power of the story all work together to make Hell’s Heroes feel not like a movie but a relic, in the best sense of the word — something rare and precious brought back by a time traveler just returned from 1880 or 1900.

As things turned out, young Mr. Wyler fought his weary way through life rather well, with or without Peter Kyne’s help, and Kyne himself lived long enough to see it. By the time Kyne died in 1957, he had seen — or could have, if he cared to notice — Wyler direct two of his three best picture Oscar winners, win two of his three Oscars for direction, and receive ten of his twelve Oscar nominations.

I’ll have more to say about Wyler later. This is just a respectful — I might even say, given the subject matter, reverent — look back at the movie that really put him on the map. If it really was lost, as Jan Herman said, in 1995, it’s not anymore. Hallelujah.

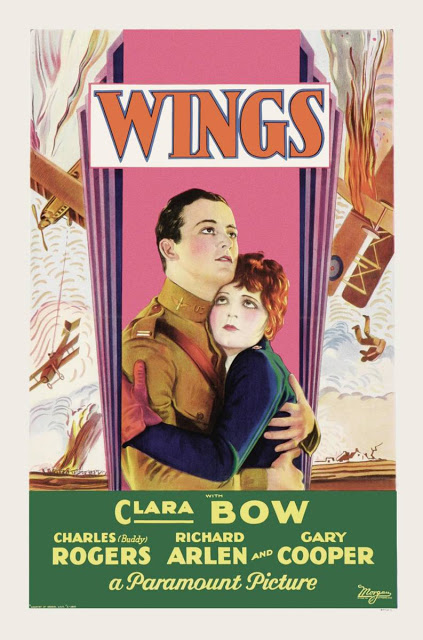

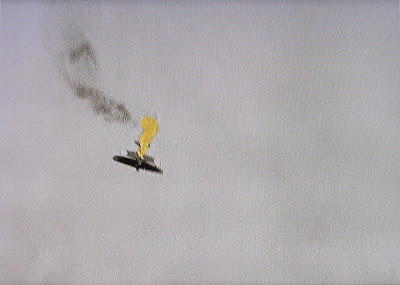

I would venture to guess that in the transfer to home video, no silent picture — perhaps no picture, period — has ever been as lovingly and carefully treated as Wings; Paramount Home Video can be as proud of the transfer as they are of the picture itself, for both are justified.

I would venture to guess that in the transfer to home video, no silent picture — perhaps no picture, period — has ever been as lovingly and carefully treated as Wings; Paramount Home Video can be as proud of the transfer as they are of the picture itself, for both are justified.

Last but absolutely not least, Wings has this young lady. Let me say this as plainly as I can: There was never a more charming and delightful movie star than Clara Bow. Plenty who were as delightful, certainly, but none more so. Ever. (If you don’t know Clara’s work, Mantrap [1926] and It [’27] are good places to start. For that matter, so is Wings.) She was the hottest star in Hollywood in 1927 (in every sense of the word), so naturally she’s top-billed in Wings, but it’s really a supporting role, almost a cameo; she plays the adoring, neglected girl next door who follows Buddy Rogers to France as a member of the Women’s Motor Corps. When Buddy’s leave in Paris is cancelled but he’s too drunk to respond, Clara goes to fetch him, only to find he’s too drunk even to recognize her, and she must dress as the flapper her fans have come to expect, all to lure him away from a French demimondaine with designs on him. (This scene also has Wellman’s most amazing non-combat shot, as the camera glides across table after table at the Folies Bergere, each with its own little drama going on: an angry woman tossing her drink in her lover’s face, a matron slipping cash to her gigolo, an adulterous couple nervously looking over their shoulders, even a pair of love-struck lesbians!)

Last but absolutely not least, Wings has this young lady. Let me say this as plainly as I can: There was never a more charming and delightful movie star than Clara Bow. Plenty who were as delightful, certainly, but none more so. Ever. (If you don’t know Clara’s work, Mantrap [1926] and It [’27] are good places to start. For that matter, so is Wings.) She was the hottest star in Hollywood in 1927 (in every sense of the word), so naturally she’s top-billed in Wings, but it’s really a supporting role, almost a cameo; she plays the adoring, neglected girl next door who follows Buddy Rogers to France as a member of the Women’s Motor Corps. When Buddy’s leave in Paris is cancelled but he’s too drunk to respond, Clara goes to fetch him, only to find he’s too drunk even to recognize her, and she must dress as the flapper her fans have come to expect, all to lure him away from a French demimondaine with designs on him. (This scene also has Wellman’s most amazing non-combat shot, as the camera glides across table after table at the Folies Bergere, each with its own little drama going on: an angry woman tossing her drink in her lover’s face, a matron slipping cash to her gigolo, an adulterous couple nervously looking over their shoulders, even a pair of love-struck lesbians!)

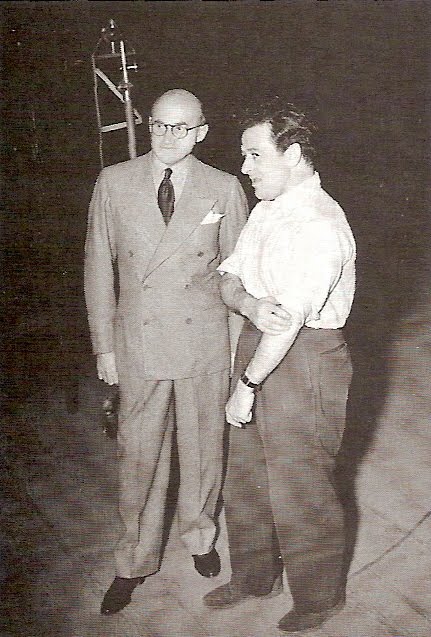

I worked with Robert Wise once. In 1986 I played a small role in Wisdom, on which he served as executive producer and all-round good shepherd for first-time writer-director Emilio Estevez. My scene was a small one, only about 45 seconds on screen, but it meant two twelve-hour days on the set. As I reported for work on my first day, Wise came up to me and introduced himself (as if it were necessary!). There was something I had thought and said about him more than once in the past, but now, to my amazement, I actually had the chance to say it to him in person: “I have to tell you, Mr. Wise, I think you’re the greatest film editor who ever picked up a pair of scissors.”

I worked with Robert Wise once. In 1986 I played a small role in Wisdom, on which he served as executive producer and all-round good shepherd for first-time writer-director Emilio Estevez. My scene was a small one, only about 45 seconds on screen, but it meant two twelve-hour days on the set. As I reported for work on my first day, Wise came up to me and introduced himself (as if it were necessary!). There was something I had thought and said about him more than once in the past, but now, to my amazement, I actually had the chance to say it to him in person: “I have to tell you, Mr. Wise, I think you’re the greatest film editor who ever picked up a pair of scissors.”

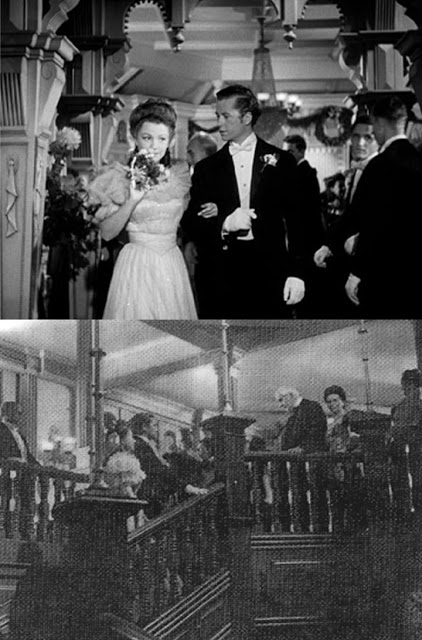

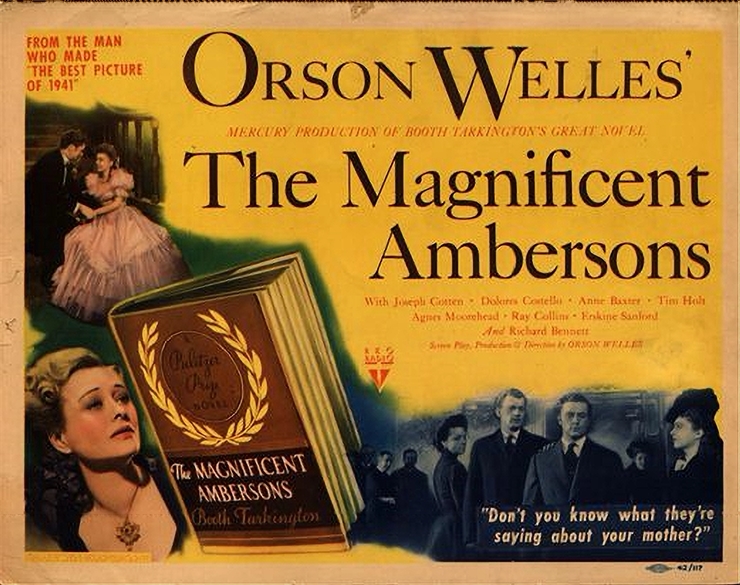

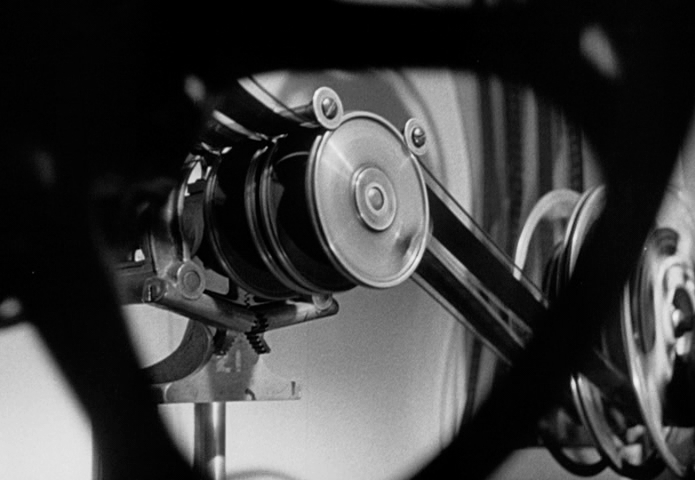

I think it may have been something simpler: that Orson Welles, for all his mastery of moviemaking so manifest in Citizen Kane, didn’t fully grasp the nuances of the editing process — not as early as 1942, anyhow. Certainly his first edits from Rio must have looked capricious and arbitrary, so much so that Wise and Moss immediately reversed them after they played so badly in Pomona. Then when Welles doubled down on the “big cut”, wanted to eliminate the end of the Amberson ball and the iris-out in the snow scene, and capped it all with a bizarre idea for a cheery curtain call “to leave audience happy”, how could it not look as if Welles had lost his train of thought on Ambersons, or simply didn’t understand how these changes would play?

I think it may have been something simpler: that Orson Welles, for all his mastery of moviemaking so manifest in Citizen Kane, didn’t fully grasp the nuances of the editing process — not as early as 1942, anyhow. Certainly his first edits from Rio must have looked capricious and arbitrary, so much so that Wise and Moss immediately reversed them after they played so badly in Pomona. Then when Welles doubled down on the “big cut”, wanted to eliminate the end of the Amberson ball and the iris-out in the snow scene, and capped it all with a bizarre idea for a cheery curtain call “to leave audience happy”, how could it not look as if Welles had lost his train of thought on Ambersons, or simply didn’t understand how these changes would play?