As a rule, Cinedrome doesn’t concern itself with the contemporary movie scene, or with any movie made after, say, 1964 or so (that being the year to which I more or less arbitrarily date the end of Hollywood’s Golden Age). But rules are for breaking, after all, and I last broke that one in February 2019, when I wrote that Mary Poppins Returns was manifestly the best and most enduring movie of 2018 (when I bought the Blu-ray in early ’19, I told the twenty-something Target clerk who rang it up, “It’s the only movie from last year that your great-grandchildren will know.”) I used that observation to segue into a discussion of the long shadow of Walt Disney. My original plan was to follow up with a second post about the contentious relationship between author P.L. Travers and Disney’s Bill Walsh, Don Da Gradi and the Sherman Brothers in crafting the script, with possibly a sidebar discussion of 2013’s bucket of enjoyable hogwash Saving Mr. Banks, which purported to tell the same story. But in reading up on it, I found the querulous, intransigent Ms. Travers such churlish and unpleasant company that I dropped the idea early on, and that follow-up post (“Mary Poppins: Enter the Dragon”) never materialized.

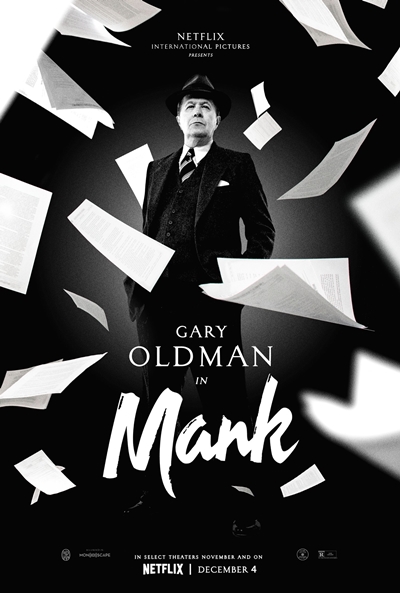

Well, that was then, this is now, and I’m breaking that rule again to discuss another contemporary movie and another long shadow. The movie is Mank, directed by David Fincher from a script by his father Jack, and the shadow belongs to Citizen Kane (1941). The younger Fincher appears to have undertaken Mank as a tribute to his father, who died in 2003 (the movie is dedicated to his memory). Besides that, it fits into the intermittent vogue for making movies about the making of movies — that is, about the making of specific movies. It’s a sub-genre that dates back at least as far as 1980’s TV movie The Scarlett O’Hara War, in which 55-year-old Tony Curtis played the 35-year-old David O. Selznick beating the bushes to find a leading lady for Gone With the Wind. The vogue has cropped up from time to time ever since; examples include the aforementioned Saving Mr. Banks and 2012’s Hitchcock, about the making of Psycho. Even Citizen Kane‘s production has been done before, in RKO 281 (1999), with Liev Schreiber as Orson Welles and James Cromwell as William Randolph Hearst.

Well, that was then, this is now, and I’m breaking that rule again to discuss another contemporary movie and another long shadow. The movie is Mank, directed by David Fincher from a script by his father Jack, and the shadow belongs to Citizen Kane (1941). The younger Fincher appears to have undertaken Mank as a tribute to his father, who died in 2003 (the movie is dedicated to his memory). Besides that, it fits into the intermittent vogue for making movies about the making of movies — that is, about the making of specific movies. It’s a sub-genre that dates back at least as far as 1980’s TV movie The Scarlett O’Hara War, in which 55-year-old Tony Curtis played the 35-year-old David O. Selznick beating the bushes to find a leading lady for Gone With the Wind. The vogue has cropped up from time to time ever since; examples include the aforementioned Saving Mr. Banks and 2012’s Hitchcock, about the making of Psycho. Even Citizen Kane‘s production has been done before, in RKO 281 (1999), with Liev Schreiber as Orson Welles and James Cromwell as William Randolph Hearst.

Mank covers ground similar to RKO 281, but concentrating not on Welles (played by Tom Burke as a drive-by cameo) but on co-writer Herman J. Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman). In the spring of 1940, after hashing out with Welles a rough outline of what would become Citizen Kane, Mankiewicz was dispatched to a distraction-free exile in Victorville, in the middle of California’s Mojave Desert, to crank out a first draft. He was encased in a half-body cast after thrice-breaking his leg in September ’39 in an auto accident en route to New York. He had just been fired from MGM and was headed east to beg work from friends, having burned too many bridges in Hollywood; his convalescence put the kibosh on that, but it led to the job with Welles.

Accompanying Mankiewicz to Victorville was a German nurse (named “Fräulein Frieda” in Mank and played by Monika Grossman); an English secretary, Rita Alexander (Lily Collins), whose last name would be used for Charles Foster Kane’s second wife; and Welles’s former producer John Houseman (Sam Troughton), who had had a violent falling-out with the Boy Genius but was coaxed back for this assignment at Mankiewicz’s request. Mank covers the twelve weeks the group spent writing, editing, and (in Mankiewicz’s case) recuperating in Victorville, with flashbacks to Herman’s feckless, self-destructive career in Hollywood to that time.

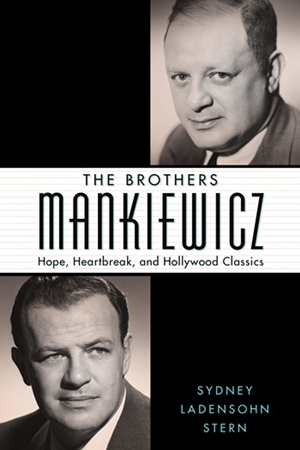

As luck would have it, the theatrical-and-streaming release of Mank followed close on the heels of my reading Sydney Ladensohn Stern’s definitive dual biography The Brothers Mankiewicz: Hope, Heartbreak, and Hollywood Classics. Ms. Stern’s subject, of course, is not only Herman J. Mankiewicz but his kid brother Joseph L., their literary ambitions and cinematic achievements. Both spent their lives hungry for the approval of their college professor father, who always seemed to feel his sons were wasting their abilities by working in movies. She makes a convincing case that Herman’s accomplishments arguably surpassed those of “Pop”, and that Joe’s undeniably surpassed them both, yet neither quite managed (if only in their own eyes) to live up to Pop’s expectations.

The Brothers Mankiewicz was published just over a year ago, much too late for Ms. Stern’s research and insights to have benefited Fincher père when he wrote Mank, or Fincher fils when he filmed it, but in plenty of time to pique our interest in their movie — at least it piqued mine — and to let us compare it with the historical record.

The impetus for this post was an email from my friend Jean in Spokane, Washington, who asked me what I thought of it. She said she had a “fairly middle of the road reaction to it overall”; she “did find it a bit long” but was fascinated by “the way it presents the characters — the Mankiewiczes, Mayer, Thalberg, Hearst et al.” and was particularly impressed by Amanda Seyfried’s performance as Marion Davies. She also spoke well of Tom Burke as Welles. I told her that no, I hadn’t seen Mank yet, but I was looking forward to it, especially now that I’d read Sydney Stern’s book — twice: once to myself, then again to my uncle.

Speaking of people playing Orson Welles in movies [I wrote her], have you by any chance seen Richard Linklater’s Me and Orson Welles (2008)? I urge you to give it a look; it’s a modest masterpiece. It’s based on a 2003 novel by Robert Kaplow; Zac Efron plays this high school kid in 1937 who stumbles into a sort of internship with the Mercury Theatre and works on Orson Welles’s modern-dress Fascist-themed production of Julius Caesar. Welles is played by one Christian McKay, and he’s absolutely uncanny. Should have won an Academy Award, but like most people who deserve Oscars, he wasn’t even nominated; besides, it was 2008, and that was the year they decided to give it to Heath Ledger for being dead. The movie is a brilliant portrait of Welles at a time when his career was still rocketing upward, with the sky seemingly the limit, and Welles himself was like an unstoppable force of nature, by turns inspiring and insufferable, but always Herculean and awe-inspiring. Also, it’s probably as close as we’ll ever get to feeling the impact of that Caesar (scenes from which were, I understand, painstakingly researched and recreated). It’s also brilliantly cast; McKay is actually just first among equals. This is all the more impressive in that there are only three major characters who are fictitious, played by Efron, Claire Danes and Zoe Kazan. Just about everybody else in the cast is not only historical, but familiar from countless movies – Joseph Cotten, Martin Gabel, John Houseman, John Hoyt, Norman Lloyd, George Coulouris, Les Tremayne. All of them perfect, especially a fellow named James Tupper as Joseph Cotten – I mean, how would you go about even looking for the ideal Joseph Cotten? So kudos to Lucy Bevan, the casting director (casting directors are often unsung heroes of movies, and never more so than here). (And by the way, in case you didn’t notice, dear old Norman Lloyd is still with us, bless his heart, having turned 106 exactly one month ago; continued long life to him, say I.) (UPDATE 6/20/21: Norman Lloyd passed away on May 11, 2021 at age 106.)

And so it was, with the memory of Me and Orson Welles fairly fresh in my mind, that I sat down a couple of nights later to watch Mank on Netflix. What follows it what I wrote to Jean a few days after that.

* * *

Hi Jean —

I watched Mank the other night, and I’ve spent the last couple of days mulling over what to tell you about it, and I finally decided what the hell, I might as well cut to the chase.

I detested it. I found it to be a pompous, overstuffed, bloviating gasbag of a movie, a comically dumb-ass parade of falsehoods great and small. I’ll start with the great ones – which, paradoxically, are the least important. By “great” I mean the movie as a chronicle of the writing of Citizen Kane. Bullcrap from first frame to last. I hardly know where to begin with its tin-eared idiocies, but a few more-or-less random thoughts:

Marion Davies went to her grave insisting that she never saw Citizen Kane, and while I’m not sure I believe that, it was her story and she stuck to it to the end. In any case, the idea that she would have driven out to Victorville to sit on the porch critiquing the fine points of Mankiewicz’s script before shooting even started is just plain stupid.

Marion Davies went to her grave insisting that she never saw Citizen Kane, and while I’m not sure I believe that, it was her story and she stuck to it to the end. In any case, the idea that she would have driven out to Victorville to sit on the porch critiquing the fine points of Mankiewicz’s script before shooting even started is just plain stupid.

Also, somewhere along the line the movie goes off onto a completely irrelevant tangent about Upton Sinclair’s 1934 campaign for governor of California, and the fake newsreels MGM made to undermine him. (This may be why you found it “a bit long”; cutting this wild goose chase could have saved half an hour to 45 minutes.) Herman Mankiewicz had nothing to do with any of that, and none of that had anything to do with writing Citizen Kane. I don’t know why it was even there (honestly, by that time my attention had already begun to wander), but it appeared to me that the movie was suggesting that Mankiewicz somehow undertook Kane as revenge against Hearst for spearheading the torpedoing of Sinclair’s campaign, and for helping drive Mankiewicz’s pal Shelly Metcalf to suicide out of shame over his part in it. Bollocks, bollocks, and bollocks. To begin with, “Shelly Metcalf” never existed, and nobody in Hollywood cared that Upton Sinclair lost the election or that MGM’s “newsreels” had anything to do with it. Certainly nobody killed themselves out of guilt over it — that’s a daydream of 21st century leftists.

At one point Mankiewicz tells Marion Davies, in one of their soulful moonlight chats on the grounds at San Simeon (itself a silly invention), that L.B. Mayer loathes Sinclair because Sinclair wrote that he “took a bribe to look the other way so a rival could buy MGM.” Another crock. The movie doesn’t say who this “rival” was, but it may be a reference to William Fox, who in the late 1920s did indeed embark on a project to buy every studio in Hollywood, intending to monopolize the business. (Adolph Zukor at Paramount had tried something similar in the late 1910s, and Thomas Edison before him. Monopoly-building has always been a tempting pastime in the movie business, and such efforts continue to this day.) Fox started by aiming big and, yes, he did try to buy MGM. He came pretty close, too — but far from looking the other way, Mayer (and Thalberg) fought doggedly against the deal. Almost to no avail; Fox came very near to pulling it off. Then, in the summer of 1929, Fox was in a horrible automobile accident that damn near killed him. He was months recuperating, and just as he was getting up and around again, the stock market crashed, taking all his credit with it. Fox was overextended, creditors pounced, and when the dust cleared he was ruined. By late 1930 he was out of the movie business forever (he lived on until 1952). He didn’t buy MGM – or rather, he did, in a way, but when the chips were down he didn’t have the cash to close the deal, and Mayer’s job at the studio was saved. I don’t know what Upton Sinclair may have written (he did write a book, Upton Sinclair Presents William Fox, published in 1933), and Mayer, a conservative Republican, may well have loathed Sinclair. But Sinclair wrote nothing about any bribe because there wasn’t one.

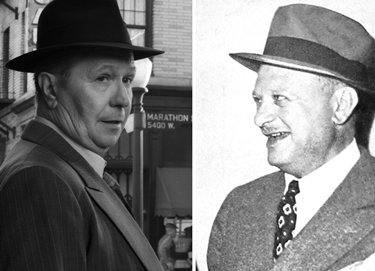

There’s hardly a detail too minor for the movie to go out of its way to get wrong. Herman Mankiewicz had a mustache in 1940. Marion Davies was sweet and well-loved, but she drank too much and, having retired from the screen in 1937, she was puffy and tending to overweight by 1939; also, she stuttered. As for Rita Alexander, no Englishwoman then, or Englishman either, would have used the word “shitty” in mixed company, even if they did think aircraft carriers were “a shitty idea” (which nobody did). That word was a pure Americanism – and for that matter, even in America few women would have said it in those days. The road accident that broke Mankiewicz’s leg happened not because a letter fluttered out of his convertible with the top down, but because Tommy Phipps, who was driving, lost control of the car in the rain on Route 66. The Mankiewicz brothers never called each other “Hermie” and “Joey”, and nobody on Planet Earth was dumb enough to call William Randolph Hearst “Willie”, even behind his back in a soundproof room.

There’s hardly a detail too minor for the movie to go out of its way to get wrong. Herman Mankiewicz had a mustache in 1940. Marion Davies was sweet and well-loved, but she drank too much and, having retired from the screen in 1937, she was puffy and tending to overweight by 1939; also, she stuttered. As for Rita Alexander, no Englishwoman then, or Englishman either, would have used the word “shitty” in mixed company, even if they did think aircraft carriers were “a shitty idea” (which nobody did). That word was a pure Americanism – and for that matter, even in America few women would have said it in those days. The road accident that broke Mankiewicz’s leg happened not because a letter fluttered out of his convertible with the top down, but because Tommy Phipps, who was driving, lost control of the car in the rain on Route 66. The Mankiewicz brothers never called each other “Hermie” and “Joey”, and nobody on Planet Earth was dumb enough to call William Randolph Hearst “Willie”, even behind his back in a soundproof room.

But honestly, none of that is really important; in fact, it’s all beside the point. I mean, if you want to know about the gunfight at the O.K. Corral, you don’t watch John Sturges’s 1957 movie, or even John Ford’s My Darling Clementine; nor do you go to The Adventures of Robin Hood for insights about Medieval England in the reign of Richard I (or for that matter, to Shakespeare about Richard III). You certainly don’t sit through Lawrence of Arabia, your butt going permanently numb, if you want to know anything about T.E. Lawrence. So the fact that Mank falsifies the writing of Citizen Kane and the career of Herman J. Mankiewicz beyond any semblance of the actual events, is not what matters. The salient fact about Mank is simply that it’s a lousy movie.

I can’t really fault the actors, except that the roles they’re shoved into are unplayable and none of them seems to have complained about it. At a minimum, they do struggle bravely with dialogue that positively bristles with name-dropping howlers:

“Mark my words, The Wizard of Oz will sink that studio.”

“Well, you know most everyone here. Mr. Kaufman…” “‘George’ is fine, kid.” “…Mr. Perelman…” “Do you prefer Sidney or S.J.?”

“Aimee Semple McPherson says you’re a godless commie, Upton!”

“We all want to welcome the Thalbergs back from Irving’s long convalescence in Europe…”

“L.B., this is my brother Joe.” “Nice to meet you, Joseph, I’m Louis Mayer.” (As if Mayer would find it necessary to introduce himself to someone in his own office!)

“You all know Jo von Sternberg…”

“I love Lowell Thomas’s voice. I sat across from him at the Brown Derby once.”

“How is Marie Antoinette coming along?” “Norma is a nervous wreck.”

“That’s Herman Mankiewicz. He wrote one of our Lon Chaneys.”

“I know you, we met at John Gilbert’s birthday party; you’re Herman Mankiewicz…You fractured Wally Beery’s wrist Indian wrestling.”

There’s hardly a minute without such low-camp groaners. I’d love to go on, but you get the idea; the script is a chortler’s paradise.

The look of the movie is flat and murky. Not “evocative” or “atmospheric”, just dark and indistinct. It was shot in something called “Hi-Dynamic Range”, whatever the hell that is. Faces, even architectural details, are lost in shadows or merge into background darkness. The cinematography, credited to someone named Erik Messerschmidt, is perfectly atrocious. It’s obvious Messerschmidt didn’t light the film for black and white, he lit it for color and shot it that way, then just leached the color out, as if that’s the same thing. You light a subject differently for black and white than you do for color, a fact that they used to teach you in the first ten minutes of Photography 101. Either Mr. Messerschmidt cut class that day or he’s merely incompetent (that’s my vote). Either way, he’s in well over his head here, and I intend to remember that name.

Late in the movie, I think at the climax (such as it was), there was a long scene in the “Refectory” at San Simeon (although in Messerschmidt’s hands it just looked like a rather well-furnished cave). The scene seemed to be terribly important; anyhow, it had Gary Oldman going tooth-and-nail for his second Oscar. But by that time the movie had completely lost me and I was no longer even pretending to pay attention; I just sat there rolling my eyes and making that wrist-rotating gesture that is the universal signal for let’s-wind-this-thing-up-already. (I couldn’t help remembering something Pauline Kael wrote in one of her reviews: “Sitting in the darkened theater, I kept listening for snorts, but every time I heard one I could feel the breath on my hands.”) Somewhere in this seemingly-terribly-important scene, Mankiewicz puked and made his famous wisecrack about the white wine coming up with the fish (which actually happened at the home of Arthur Hornblow Jr.), but that’s really all I remember. I was just marking time, waiting for this ridiculous, fraudulent movie to be over. And then…finally…it was.

Late in the movie, I think at the climax (such as it was), there was a long scene in the “Refectory” at San Simeon (although in Messerschmidt’s hands it just looked like a rather well-furnished cave). The scene seemed to be terribly important; anyhow, it had Gary Oldman going tooth-and-nail for his second Oscar. But by that time the movie had completely lost me and I was no longer even pretending to pay attention; I just sat there rolling my eyes and making that wrist-rotating gesture that is the universal signal for let’s-wind-this-thing-up-already. (I couldn’t help remembering something Pauline Kael wrote in one of her reviews: “Sitting in the darkened theater, I kept listening for snorts, but every time I heard one I could feel the breath on my hands.”) Somewhere in this seemingly-terribly-important scene, Mankiewicz puked and made his famous wisecrack about the white wine coming up with the fish (which actually happened at the home of Arthur Hornblow Jr.), but that’s really all I remember. I was just marking time, waiting for this ridiculous, fraudulent movie to be over. And then…finally…it was.

So for what it’s worth, that’s my reaction to Mank, a silly and terrible movie where not a scene, not a minute, not a second, not a frame has the ring of truth – plus it’s ugly to look at, and it’s more trouble trying to peer through the stygian gloom than it’s worth. It’s 131 minutes I’ll never get back, but on the whole I might well have frittered the time away on something almost as useless, so no great harm done. Still, having gotten it out of the way, I now dismiss it from my mind forever, and I intend never to give it another moment’s thought.

On the other hand, I can’t wait to watch Me and Orson Welles again. Now that’s how it’s done.

All for now; write when you can.

Jim

A precocious student with an artistic bent, Olivia caught the acting bug as a teenager, making her debut at 16 playing Lewis Carroll’s Alice for the Saratoga Community Players. Her stepfather, a real petty tyrant, disapproved, and he tried putting his foot down after she was cast in a school production of Pride and Prejudice. None of this acting nonsense, he decreed, not if she wanted to live under his roof — only to learn the lesson others would learn when they tried pushing Olivia de Havilland around: She moved in with a family friend, and the show (and Olivia) went on.

A precocious student with an artistic bent, Olivia caught the acting bug as a teenager, making her debut at 16 playing Lewis Carroll’s Alice for the Saratoga Community Players. Her stepfather, a real petty tyrant, disapproved, and he tried putting his foot down after she was cast in a school production of Pride and Prejudice. None of this acting nonsense, he decreed, not if she wanted to live under his roof — only to learn the lesson others would learn when they tried pushing Olivia de Havilland around: She moved in with a family friend, and the show (and Olivia) went on.

Now before we go on, let’s pause to consider how Captain Blood might have turned out with Robert Donat and Marion Davies. Fortunately, we were spared that. Instead of Donat and Davies, we got Captain Blood with Errol and Olivia, and it made stars of them both. In eight pictures together, they shared a reserved grace that provided a good complement each for the other. Not to mention an erotic chemistry so strong that in those few pictures where their characters don’t end up together — like The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936) and Four’s a Crowd (1938) — something seems distinctly out of whack.

Now before we go on, let’s pause to consider how Captain Blood might have turned out with Robert Donat and Marion Davies. Fortunately, we were spared that. Instead of Donat and Davies, we got Captain Blood with Errol and Olivia, and it made stars of them both. In eight pictures together, they shared a reserved grace that provided a good complement each for the other. Not to mention an erotic chemistry so strong that in those few pictures where their characters don’t end up together — like The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936) and Four’s a Crowd (1938) — something seems distinctly out of whack.

Over the years the sisters — protesting a bit too much, perhaps — would sometimes pose for photos to show that things were just fine between them. They were always burying the hatchet, and always remembering where they left it. The “final schism”, as Joan phrased it, seems to have come with their mother’s terminal illness in 1975. Joan, on tour in Cactus Flower, felt slighted at being excluded from end-of-life treatment decisions; worse, she felt Olivia was dilatory in letting her know when the end was near, so she was still on the road when Mummy breathed her last. At the memorial service, Joan refused to speak to her older sister. Three years later, in her autobiography, Joan, like a volcano that would not stop, spewed sixty years’ worth of pent-up hostility — prompted, perhaps, by still-tender wounds about their mother. In an interview promoting the book she said, “You can divorce your sister as well as your husbands. I don’t see her and I don’t intend to.” In public, Olivia maintained a lofty silence; privately she took to calling Joan the Dragon Lady. Joan titled her memoir No Bed of Roses. Olivia dubbed it No Shred of Truth.

Over the years the sisters — protesting a bit too much, perhaps — would sometimes pose for photos to show that things were just fine between them. They were always burying the hatchet, and always remembering where they left it. The “final schism”, as Joan phrased it, seems to have come with their mother’s terminal illness in 1975. Joan, on tour in Cactus Flower, felt slighted at being excluded from end-of-life treatment decisions; worse, she felt Olivia was dilatory in letting her know when the end was near, so she was still on the road when Mummy breathed her last. At the memorial service, Joan refused to speak to her older sister. Three years later, in her autobiography, Joan, like a volcano that would not stop, spewed sixty years’ worth of pent-up hostility — prompted, perhaps, by still-tender wounds about their mother. In an interview promoting the book she said, “You can divorce your sister as well as your husbands. I don’t see her and I don’t intend to.” In public, Olivia maintained a lofty silence; privately she took to calling Joan the Dragon Lady. Joan titled her memoir No Bed of Roses. Olivia dubbed it No Shred of Truth.  Olivia eventually got her own Oscar, of course. Two of them, in fact, and both at Paramount, the studio that had borrowed her for Hold Back the Dawn. First, in 1946, came To Each His Own. Olivia played an unwed mother who, when her lover is killed in World War I, is forced to give up her baby to be adopted by an old frenemy, then to watch from afar as the boy grows up, thinking of her only as a fussy and rather pathetic family friend. It was, in Oscar historian Robert Osborne’s apt phrase, “a Tiffany tear-jerker”. In the movie’s final scene, when the boy, now grown to manhood, finally gets it through his head why “Aunt Jody” has always been so nice to him, and says to her, “May I have this dance…Mother?” — the look on Olivia’s face is enough to reduce a bronze statue to helpless sobs.

Olivia eventually got her own Oscar, of course. Two of them, in fact, and both at Paramount, the studio that had borrowed her for Hold Back the Dawn. First, in 1946, came To Each His Own. Olivia played an unwed mother who, when her lover is killed in World War I, is forced to give up her baby to be adopted by an old frenemy, then to watch from afar as the boy grows up, thinking of her only as a fussy and rather pathetic family friend. It was, in Oscar historian Robert Osborne’s apt phrase, “a Tiffany tear-jerker”. In the movie’s final scene, when the boy, now grown to manhood, finally gets it through his head why “Aunt Jody” has always been so nice to him, and says to her, “May I have this dance…Mother?” — the look on Olivia’s face is enough to reduce a bronze statue to helpless sobs. Also at 100, she showed the world that there was litigation in the old girl yet. She sued FX Networks and producer Ryan Murphy over Feud: Bette and Joan, an eight-part miniseries that purported to dish the dirt on the making of What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? in 1962 and the diva-rivalry between Bette Davis and Joan Crawford. Olivia had been a good friend of Bette’s, and she replaced Joan when she was fired from her and Bette’s follow-up teaming on Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964), so Olivia was represented as a supporting character in the miniseries, and played by Catherine Zeta-Jones. As these two pictures suggest, neither Ms. Zeta-Jones, her costumer, nor her hairdresser gave much evidence of ever having seen or heard of Olivia. Neither did any of the writers, and that’s what she sued over, charging that her privacy had been invaded without her permission or input, that she had been slandered and misrepresented. True enough; Feud was sleazy stuff, despite all the A-list names, and it misrepresented pretty much everybody it mentioned. The only reason Olivia was the only plaintiff in the case is that she was the only one who was still alive.

Also at 100, she showed the world that there was litigation in the old girl yet. She sued FX Networks and producer Ryan Murphy over Feud: Bette and Joan, an eight-part miniseries that purported to dish the dirt on the making of What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? in 1962 and the diva-rivalry between Bette Davis and Joan Crawford. Olivia had been a good friend of Bette’s, and she replaced Joan when she was fired from her and Bette’s follow-up teaming on Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964), so Olivia was represented as a supporting character in the miniseries, and played by Catherine Zeta-Jones. As these two pictures suggest, neither Ms. Zeta-Jones, her costumer, nor her hairdresser gave much evidence of ever having seen or heard of Olivia. Neither did any of the writers, and that’s what she sued over, charging that her privacy had been invaded without her permission or input, that she had been slandered and misrepresented. True enough; Feud was sleazy stuff, despite all the A-list names, and it misrepresented pretty much everybody it mentioned. The only reason Olivia was the only plaintiff in the case is that she was the only one who was still alive.

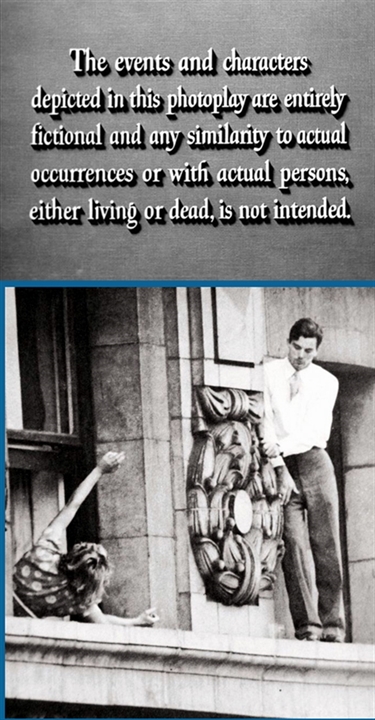

This title card appears early in Henry Hathaway’s Fourteen Hours — at the “climax” of the opening credits, you might say, just before the credit cards for producer Sol C. Siegel and director Hathaway. It’s the standard “entirely fictional and any similarity” disclaimer, the kind that usually appears in super-small type somewhere near the copyright notice, the MPAA “approved” certificate number, the Western Electric and IATSE credits, and other things that are legally required but nobody really cares if you see or not. For this picture, though, 20th Century Fox took the unusual step of making sure the disclaimer was very prominently placed where even the most inattentive could hardly miss it.

This title card appears early in Henry Hathaway’s Fourteen Hours — at the “climax” of the opening credits, you might say, just before the credit cards for producer Sol C. Siegel and director Hathaway. It’s the standard “entirely fictional and any similarity” disclaimer, the kind that usually appears in super-small type somewhere near the copyright notice, the MPAA “approved” certificate number, the Western Electric and IATSE credits, and other things that are legally required but nobody really cares if you see or not. For this picture, though, 20th Century Fox took the unusual step of making sure the disclaimer was very prominently placed where even the most inattentive could hardly miss it.

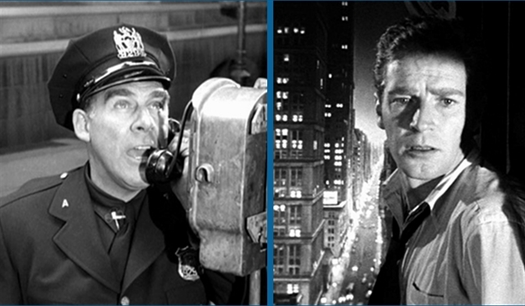

The picture opens quietly — in silence, in fact, without dialogue or even background music. (Indeed, except for Alfred Newman’s fervid theme under the opening credits, then a second theme swelling through the movie’s last 90 seconds, there’s no music in the entire picture.) We are introduced to what will prove to be the two central characters in the drama that follows. First we see Patrolman Charlie Dunnigan (Paul Douglas as the movie’s version of Charles Glasco) walking his beat in the early morning calm. He passes the Rodney Hotel, where a worker is polishing the brass plate at the entrance. Meanwhile, up in Room 1505…

The picture opens quietly — in silence, in fact, without dialogue or even background music. (Indeed, except for Alfred Newman’s fervid theme under the opening credits, then a second theme swelling through the movie’s last 90 seconds, there’s no music in the entire picture.) We are introduced to what will prove to be the two central characters in the drama that follows. First we see Patrolman Charlie Dunnigan (Paul Douglas as the movie’s version of Charles Glasco) walking his beat in the early morning calm. He passes the Rodney Hotel, where a worker is polishing the brass plate at the entrance. Meanwhile, up in Room 1505…

Then the silence is rudely broken by the first human sound we hear — a secretary screaming in the window of a bank building across the street. Dunnigan dashes into the hotel to alert the staff, while the waiter calls down to the switchboard for the same reason. Dunnigan and Harris, the assistant manager (Willard Waterman), knowing now which room to go to, head up in the elevator. In the room, Harris blusters at Robert to come inside, sounding like an impotent scold.

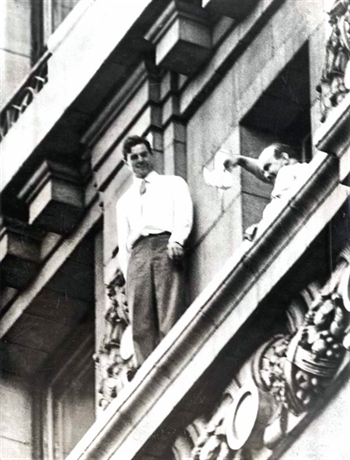

Then the silence is rudely broken by the first human sound we hear — a secretary screaming in the window of a bank building across the street. Dunnigan dashes into the hotel to alert the staff, while the waiter calls down to the switchboard for the same reason. Dunnigan and Harris, the assistant manager (Willard Waterman), knowing now which room to go to, head up in the elevator. In the room, Harris blusters at Robert to come inside, sounding like an impotent scold.  The colloquy between Charlie Dunnigan and Robert Cosick, a mixture of urgent pleading and forced-casual chitchat, provides the spine of Fourteen Hours, just as the real one between Charles Glasco and John Warde did for Joel Sayre’s New Yorker article. (Notice too how Joe MacDonald’s deep-focus photography emphasizes both men’s perilous perch 15 stories up. MacDonald was a master cinematographer who worked with Hathaway on nine pictures, including some of his best.)

The colloquy between Charlie Dunnigan and Robert Cosick, a mixture of urgent pleading and forced-casual chitchat, provides the spine of Fourteen Hours, just as the real one between Charles Glasco and John Warde did for Joel Sayre’s New Yorker article. (Notice too how Joe MacDonald’s deep-focus photography emphasizes both men’s perilous perch 15 stories up. MacDonald was a master cinematographer who worked with Hathaway on nine pictures, including some of his best.)  Over this bare factual skeleton Paxton’s script skillfully weaves a variety of fictional stories among the people drawn for one reason or another to the Rodney Hotel and the street outside. It amounts to a cross-section of the New York public circa 1950 — and for all the changes the city has seen in 69 years, it still rings true today.

Over this bare factual skeleton Paxton’s script skillfully weaves a variety of fictional stories among the people drawn for one reason or another to the Rodney Hotel and the street outside. It amounts to a cross-section of the New York public circa 1950 — and for all the changes the city has seen in 69 years, it still rings true today. Elsewhere in the crowd the reaction is more compassionate. Two young office workers, Ruth (Debra Paget, left) and Barbara (Joyce Van Patten, right), have gotten sidetracked on their way to work. The fretful Barbara wants only to get to work before they get in trouble with the boss. But Ruth is more worried about the stranger on the fifteenth floor: How old is he? What kind of trouble is he in? “Maybe someone was cruel to him, or maybe he’s just lonely…I wish I could help him.” Her tender words catch the ear of Danny behind her (Jeffrey Hunter), also pausing on his way to work. When Barbara gives up and leaves, Danny and Ruth strike up a sweetly tentative conversation. As the day wears on, neither of them will get to work. Feelings grow between them, and Danny reflects on how they might have gone their whole lives, missing each other by minutes, if it hadn’t been for this day. Hunter and the 17-year-old Paget were already launched on their successful careers as Fox contract players. Van Patten, making her film debut at 16, would in time become one of television’s busiest character actresses in a career that is still going strong today.

Elsewhere in the crowd the reaction is more compassionate. Two young office workers, Ruth (Debra Paget, left) and Barbara (Joyce Van Patten, right), have gotten sidetracked on their way to work. The fretful Barbara wants only to get to work before they get in trouble with the boss. But Ruth is more worried about the stranger on the fifteenth floor: How old is he? What kind of trouble is he in? “Maybe someone was cruel to him, or maybe he’s just lonely…I wish I could help him.” Her tender words catch the ear of Danny behind her (Jeffrey Hunter), also pausing on his way to work. When Barbara gives up and leaves, Danny and Ruth strike up a sweetly tentative conversation. As the day wears on, neither of them will get to work. Feelings grow between them, and Danny reflects on how they might have gone their whole lives, missing each other by minutes, if it hadn’t been for this day. Hunter and the 17-year-old Paget were already launched on their successful careers as Fox contract players. Van Patten, making her film debut at 16, would in time become one of television’s busiest character actresses in a career that is still going strong today. Needless to say, New York’s newshounds are also Johnny-on-the-spot. Newspapermen swarm over the scene like ants on a sugar cube. New York announcer George Putnam, playing himself, gives a play-by-play summary from a radio truck in the street. Another radio reporter barges into Room 1505 to jam a microphone out the window to eavesdrop on Dunnigan and Robert’s conversation — only to get the bum’s rush from the vigilant police. Station WNBC dispatches a television camera crew to the roof of a building across the street from the hotel. (Curiously enough, this wasn’t just an embellishment in Paxton’s script. NBC really did broadcast TV coverage of John Warde’s exploit back in 1938, even though there probably weren’t more than a few dozen sets in the whole city, and practically none in the rest of the country. It may well have been the very first example of television covering a breaking news story.)

Needless to say, New York’s newshounds are also Johnny-on-the-spot. Newspapermen swarm over the scene like ants on a sugar cube. New York announcer George Putnam, playing himself, gives a play-by-play summary from a radio truck in the street. Another radio reporter barges into Room 1505 to jam a microphone out the window to eavesdrop on Dunnigan and Robert’s conversation — only to get the bum’s rush from the vigilant police. Station WNBC dispatches a television camera crew to the roof of a building across the street from the hotel. (Curiously enough, this wasn’t just an embellishment in Paxton’s script. NBC really did broadcast TV coverage of John Warde’s exploit back in 1938, even though there probably weren’t more than a few dozen sets in the whole city, and practically none in the rest of the country. It may well have been the very first example of television covering a breaking news story.)

While the crowd in the street mills about gawking, wringing their hands, or cracking callous jokes, up on the fifteenth floor things are in a muffled uproar. The NYPD’s rescue efforts are commanded by the officious but efficient Deputy Chief Moksar (Howard Da Silva, left), who coordinates activities while straight-arming a swarm of reporters and dealing with other interfering looky-loos (at one excruciatingly delicate moment, a crackpot preacher bursts into the room bellowing at Robert to kneel and pray). Police psychiatrist Dr. Strauss (Martin Gabel, center) offers on-the-fly advice to Moksar and Dunnigan on Robert’s mental state. Further complications come with the arrival of Robert’s divorced parents — his clutching, hysterical mother (Agnes Moorehead, second right) and feckless alcoholic father (Robert Keith, right), who graphically illustrate the Cosick family dysfunction. (“No wonder he’s cuckoo!” growls Moksar.)

While the crowd in the street mills about gawking, wringing their hands, or cracking callous jokes, up on the fifteenth floor things are in a muffled uproar. The NYPD’s rescue efforts are commanded by the officious but efficient Deputy Chief Moksar (Howard Da Silva, left), who coordinates activities while straight-arming a swarm of reporters and dealing with other interfering looky-loos (at one excruciatingly delicate moment, a crackpot preacher bursts into the room bellowing at Robert to kneel and pray). Police psychiatrist Dr. Strauss (Martin Gabel, center) offers on-the-fly advice to Moksar and Dunnigan on Robert’s mental state. Further complications come with the arrival of Robert’s divorced parents — his clutching, hysterical mother (Agnes Moorehead, second right) and feckless alcoholic father (Robert Keith, right), who graphically illustrate the Cosick family dysfunction. (“No wonder he’s cuckoo!” growls Moksar.)

Fourteen Hours was what was known as an A-minus picture — that is, a picture with an A budget but no major stars. The closest thing to one was Paul Douglas, the former sports announcer who had been one of Fox’s most popular and reliable supporting actors since his breakout work as Linda Darnell’s husband in A Letter to Three Wives (’49). In 1950 as Fourteen Hours went into production he was teetering between first and second leads, which he would continue to do for the rest of his life, until his untimely death from a heart attack in 1959 at 52. In Fourteen Hours, top-billed in a first-rate ensemble cast, he carries much of the film as his Charlie Dunnigan tries to lure Robert Cosick literally back from the brink, winging it from moment to moment with a seat-of-the-pants common sense.

Fourteen Hours was what was known as an A-minus picture — that is, a picture with an A budget but no major stars. The closest thing to one was Paul Douglas, the former sports announcer who had been one of Fox’s most popular and reliable supporting actors since his breakout work as Linda Darnell’s husband in A Letter to Three Wives (’49). In 1950 as Fourteen Hours went into production he was teetering between first and second leads, which he would continue to do for the rest of his life, until his untimely death from a heart attack in 1959 at 52. In Fourteen Hours, top-billed in a first-rate ensemble cast, he carries much of the film as his Charlie Dunnigan tries to lure Robert Cosick literally back from the brink, winging it from moment to moment with a seat-of-the-pants common sense. At the end of Fourteen Hours Robert Cosick is finally brought in through the window to safety — you’ll have to see the movie to find out exactly how that comes about. Unfortunately, the day didn’t end as happily for John William Warde. At 10:30 p.m. that night, John said to Officer Glasco, “I’ve made up my mind.” Glasco took this as an optimistic sign that John had decided to come in; at least that’s how he chose to read it. “That’s the way to talk,” he said. About that time, a childhood friend of John’s arrived in room 1714, and he relieved Glasco at the window talking to John.

At the end of Fourteen Hours Robert Cosick is finally brought in through the window to safety — you’ll have to see the movie to find out exactly how that comes about. Unfortunately, the day didn’t end as happily for John William Warde. At 10:30 p.m. that night, John said to Officer Glasco, “I’ve made up my mind.” Glasco took this as an optimistic sign that John had decided to come in; at least that’s how he chose to read it. “That’s the way to talk,” he said. About that time, a childhood friend of John’s arrived in room 1714, and he relieved Glasco at the window talking to John.

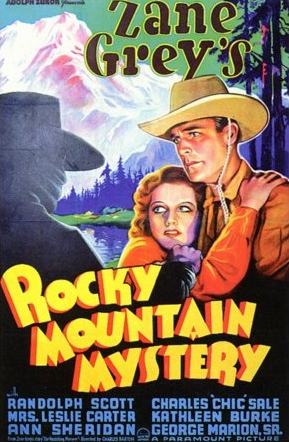

Sunday morning began with another George O’Brien B-picture directed by David Howard.

Sunday morning began with another George O’Brien B-picture directed by David Howard.  Next came

Next came  After the final three chapters of Hawk of the Wilderness came

After the final three chapters of Hawk of the Wilderness came  This brought us at last to the final picture of the weekend, a nifty little 65-minute murder mystery,

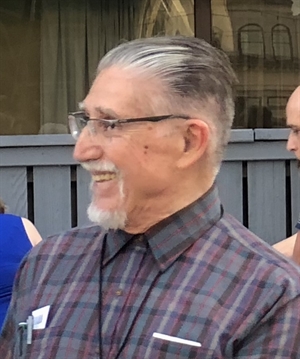

This brought us at last to the final picture of the weekend, a nifty little 65-minute murder mystery,  I don’t want to leave my survey of this year’s Cinevent without mentioning my friend Phil Capasso. Last year, at the Golden Anniversary Celebration, Phil was honored as the only person who had been to every single Cinevent since the first one back in 1969. This dedicated attendance earned him the first slice of the 50th anniversary cake that evening, not to mention the privilege of introducing Cinevent 50’s guest of honor Leonard Maltin. Needless to say, Phil was in Seventh Heaven at that party, and as happy as I’d ever seen him. Then on August 28, 2018, barely three months after I took this picture of him in Columbus, Phil passed away at his home in Carmel, Indiana, at age 82. I’m sure he was planning for his annual trek to Los Angeles for Cinecon 54 on Labor Day Weekend. And I have no doubt he was already looking forward (in his customary phrase, “if God spares”) to joining us all again in Columbus for this year’s Cinevent 51.

I don’t want to leave my survey of this year’s Cinevent without mentioning my friend Phil Capasso. Last year, at the Golden Anniversary Celebration, Phil was honored as the only person who had been to every single Cinevent since the first one back in 1969. This dedicated attendance earned him the first slice of the 50th anniversary cake that evening, not to mention the privilege of introducing Cinevent 50’s guest of honor Leonard Maltin. Needless to say, Phil was in Seventh Heaven at that party, and as happy as I’d ever seen him. Then on August 28, 2018, barely three months after I took this picture of him in Columbus, Phil passed away at his home in Carmel, Indiana, at age 82. I’m sure he was planning for his annual trek to Los Angeles for Cinecon 54 on Labor Day Weekend. And I have no doubt he was already looking forward (in his customary phrase, “if God spares”) to joining us all again in Columbus for this year’s Cinevent 51. Saturday’s

Saturday’s  After the cartoons — just like a Saturday Kiddie Matinee of my childhood — it was three more chapters of Hawk of the Wilderness. Then the Saturday Matinee mold was broken by a silent feature,

After the cartoons — just like a Saturday Kiddie Matinee of my childhood — it was three more chapters of Hawk of the Wilderness. Then the Saturday Matinee mold was broken by a silent feature,  After lunch it was the return of a longtime favorite feature at Cinevent, a program of Charley Chase comedy shorts. This year’s entries were

After lunch it was the return of a longtime favorite feature at Cinevent, a program of Charley Chase comedy shorts. This year’s entries were  Just before the dinner break came one of the surprise highlights of the whole weekend — a surprise to me, anyhow. Not because I didn’t expect it to be good, but because it was so much better than I expected. This was

Just before the dinner break came one of the surprise highlights of the whole weekend — a surprise to me, anyhow. Not because I didn’t expect it to be good, but because it was so much better than I expected. This was  Richard Barrios introduced

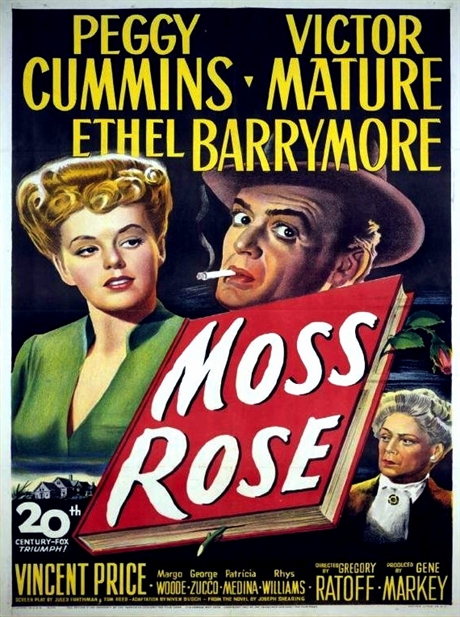

Richard Barrios introduced  Moss Rose (1947)

Moss Rose (1947) There was some important news announced on Saturday by Cinevent chair Michael Haynes (on the left in this picture, in case you need to be told) and Dealers’ Room coordinator Samantha Glasser (the one who isn’t Michael).

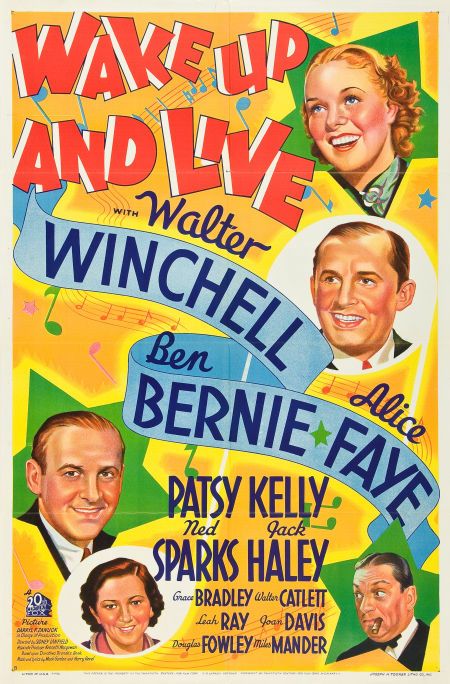

There was some important news announced on Saturday by Cinevent chair Michael Haynes (on the left in this picture, in case you need to be told) and Dealers’ Room coordinator Samantha Glasser (the one who isn’t Michael). Friday morning at Cinevent started off bright and early with one of the last of 20th Century Fox’s fanciful biopics of figures from the Golden Age of Vaudeville. Earlier years had seen highly fictionalized treatments of the lives of Lillian Russell (1940), songwriter Paul Dresser (My Gal Sal, 1942), The Dolly Sisters (1945), another songwriter, Joe Howard (I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now, 1947), Florodora girl Myrtle McKinley (Mother Wore Tights, 1947), Lotta Crabtree (Golden Girl, 1951) and even John Philip Sousa (Stars and Stripes Forever, 1952). Today’s specimen of the sub-genre was

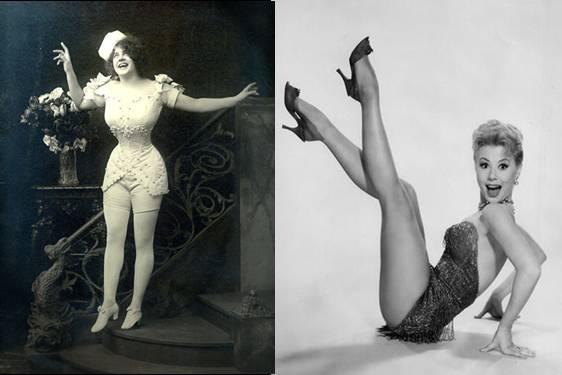

Friday morning at Cinevent started off bright and early with one of the last of 20th Century Fox’s fanciful biopics of figures from the Golden Age of Vaudeville. Earlier years had seen highly fictionalized treatments of the lives of Lillian Russell (1940), songwriter Paul Dresser (My Gal Sal, 1942), The Dolly Sisters (1945), another songwriter, Joe Howard (I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now, 1947), Florodora girl Myrtle McKinley (Mother Wore Tights, 1947), Lotta Crabtree (Golden Girl, 1951) and even John Philip Sousa (Stars and Stripes Forever, 1952). Today’s specimen of the sub-genre was  Not that it would have been easy. The Production Code was still in firm control, and Eva Tanguay’s main selling point was blatantly sexual, a lusty throwing off of the prim strictures of Victorian ladyhood (Rosen says that her dances frequently looked like simulated orgasms), where Cohan’s chief selling point was patriotism, much easier to get through the Breen Office (especially during a war). But it could have been done — just not with Bullock’s script. And, alas, even with a better script, probably not with Mitzi Gaynor either. Gaynor may well have had more talent that Tanguay, but probably not half the personality. Mitzi was basically a pretty-good chorus girl who got some fantastic breaks — sort of a Vera-Ellen, but able to do her own singing.

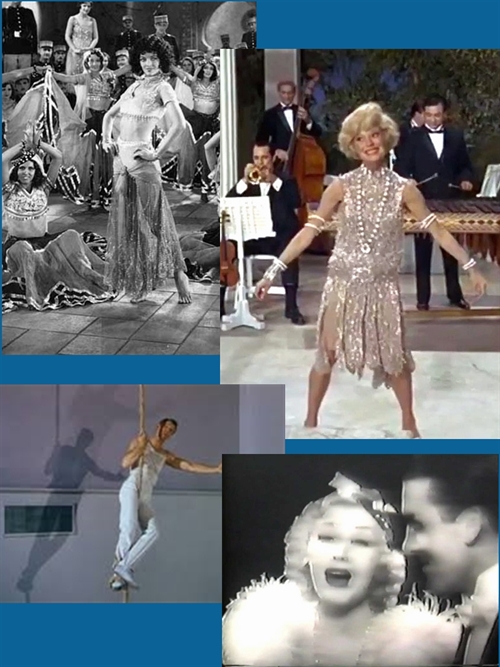

Not that it would have been easy. The Production Code was still in firm control, and Eva Tanguay’s main selling point was blatantly sexual, a lusty throwing off of the prim strictures of Victorian ladyhood (Rosen says that her dances frequently looked like simulated orgasms), where Cohan’s chief selling point was patriotism, much easier to get through the Breen Office (especially during a war). But it could have been done — just not with Bullock’s script. And, alas, even with a better script, probably not with Mitzi Gaynor either. Gaynor may well have had more talent that Tanguay, but probably not half the personality. Mitzi was basically a pretty-good chorus girl who got some fantastic breaks — sort of a Vera-Ellen, but able to do her own singing. Which brings us to the movie’s saving grace, so far as it has one. According to one version of the story, Darryl F. Zanuck saw an early cut of The I Don’t Care Girl, realized it was a dog, and ordered drastic surgery: he called in Jack Cole to punch up the musical numbers. And for the three numbers Cole staged — “Beale Street Blues”, “The Johnson Rag” and “I Don’t Care” (shown here) — the movie blazes fitfully to life. Of course, when Cole takes over, the vaudeville of 1910 flies out the window while 1950s theatrical jazz dance sashays in the door (other numbers staged by Seymour Felix are truer to the period, if less flamboyantly entertaining). Besides Cole’s work, The I Don’t Care Girl has little to recommend it, although the print shown at Cinevent beautifully conveyed the movie’s other main asset, the splendid Fox Technicolor.

Which brings us to the movie’s saving grace, so far as it has one. According to one version of the story, Darryl F. Zanuck saw an early cut of The I Don’t Care Girl, realized it was a dog, and ordered drastic surgery: he called in Jack Cole to punch up the musical numbers. And for the three numbers Cole staged — “Beale Street Blues”, “The Johnson Rag” and “I Don’t Care” (shown here) — the movie blazes fitfully to life. Of course, when Cole takes over, the vaudeville of 1910 flies out the window while 1950s theatrical jazz dance sashays in the door (other numbers staged by Seymour Felix are truer to the period, if less flamboyantly entertaining). Besides Cole’s work, The I Don’t Care Girl has little to recommend it, although the print shown at Cinevent beautifully conveyed the movie’s other main asset, the splendid Fox Technicolor. Much of the rest of the day, until the dinner break anyhow, was almost anticlimactic after the gaudy Technicolor splash of The I Don’t Care Girl.

Much of the rest of the day, until the dinner break anyhow, was almost anticlimactic after the gaudy Technicolor splash of The I Don’t Care Girl.  Then, just like that, the anticlimactic part of the day was over and Richard Barrios was back to introduce

Then, just like that, the anticlimactic part of the day was over and Richard Barrios was back to introduce  After dinner we saw a real crowd-pleaser, and a highlight of the weekend:

After dinner we saw a real crowd-pleaser, and a highlight of the weekend:  The last movie of the day was one I’ve been curious about for some time:

The last movie of the day was one I’ve been curious about for some time:  The first silent of the weekend was

The first silent of the weekend was  The next two movies on the program were considerably more rewarding. First came

The next two movies on the program were considerably more rewarding. First came  Next, after the Thursday dinner break, came the genuinely unusual, little-seen

Next, after the Thursday dinner break, came the genuinely unusual, little-seen  Besides, I didn’t want to miss the last movie of the day,

Besides, I didn’t want to miss the last movie of the day,  Cinevent this year began with something new: A tour of Columbus’s Ohio Theatre. The tour cost extra, and ran late enough to conflict with the first show in the screening room — but it was worth it on both counts.

Cinevent this year began with something new: A tour of Columbus’s Ohio Theatre. The tour cost extra, and ran late enough to conflict with the first show in the screening room — but it was worth it on both counts. As I said before, the Ohio Theatre tour ran long enough that I missed the first event in the screening room, Chapters 1-3 of this year’s serial, Republic’s

As I said before, the Ohio Theatre tour ran long enough that I missed the first event in the screening room, Chapters 1-3 of this year’s serial, Republic’s  After Hawk of the Wilderness came the first feature film of this year’s Cinevent: John Ford’s

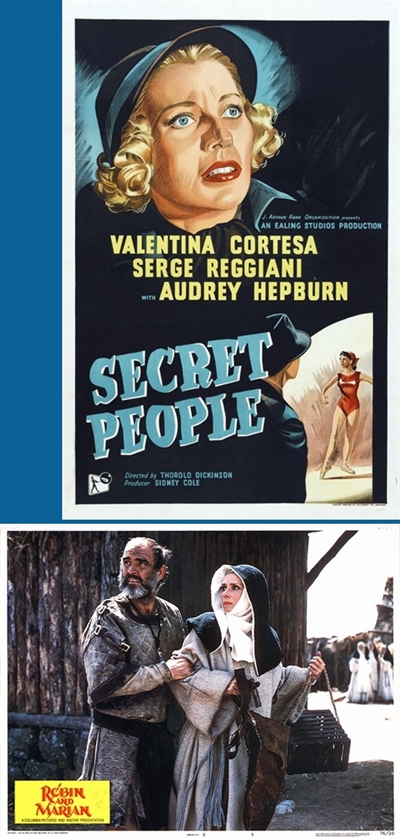

After Hawk of the Wilderness came the first feature film of this year’s Cinevent: John Ford’s  Once again, on the Wednesday night before the first day of Cinevent, some of us early arrivals in Columbus attended a screening at the Wexner Center for the Arts on the Ohio State Campus. The theme this year was “Audrey Hepburn X 2”, and the program consisted of pictures at opposite ends of Audrey’s career, one of her last (Robin and Marian, 1976) followed by one of her first (Secret People, 1952). Personally, I would have preferred that the Wexner Center take the program in chronological order rather than the reverse.

Once again, on the Wednesday night before the first day of Cinevent, some of us early arrivals in Columbus attended a screening at the Wexner Center for the Arts on the Ohio State Campus. The theme this year was “Audrey Hepburn X 2”, and the program consisted of pictures at opposite ends of Audrey’s career, one of her last (Robin and Marian, 1976) followed by one of her first (Secret People, 1952). Personally, I would have preferred that the Wexner Center take the program in chronological order rather than the reverse.