Picture Show 02 — Day 4

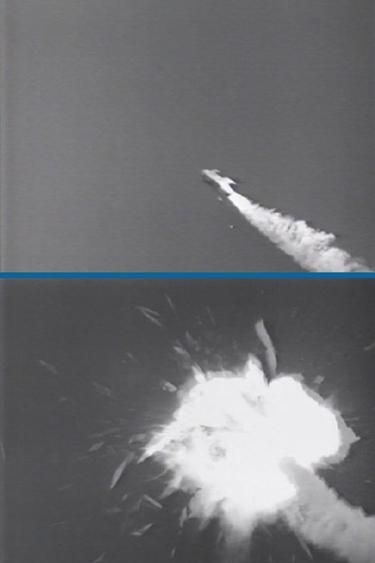

The final day of Columbus Moving Picture Show 2023 opened, naturally enough, with the final four chapters of The Purple Monster Strikes. Our slow-on-the-uptake hero, slugging-and-shooting attorney Craig Foster (Dennis Moore) finally begins to catch on that something’s not right with “Dr. Layton” (who is in fact the Purple Monster, having murdered Dr. Layton and taken over his body). Back in Chapter 11 the Emperor of Mars sent a female underling to assist the Purple Monster by killing one of the secretaries at the “jet plane” factory and taking over her body. By the way, oddly enough, when the Purple Monster arrives on Earth, he tells his hired Earthling thug, “My name would mean nothing to you; you can call me the Purple Monster.” But the female sent to aid him is named Marcia before she takes over the body of Helen. Do only women on Mars have simple names? Or is “Marcia the Martian” an alias? If so, why didn’t the Purple Monster just call himself “Martin”, like Ray Walston on 1960s TV? Then again, Martin Strikes wouldn’t have been a very dramatic title. Well, anyhow, Marcia was a little sloppy while vacating Helen’s body, and the late Dr. Layton’s niece Sheila (Linda Stirling), feigning unconsciousness, observed her in the act. This enabled Foster finally to put two and two together and plant a camera in “Dr. Layton’s” office to see if he’s doing the same thing. But even before the film is developed, the Purple Monster makes his move, absconding with the prototype “jet plane” to be reverse-engineered back on Mars. Fortunately, Foster turns the “annihilator ray” on the escaping Purple Monster and blows him out of the sky (another nifty miniature by the Lydecker Brothers). And Chapter 15 ends with the unspoken hope that future extraterrestrial invaders will be no smarter than this one was. There would in fact be three more such invasions courtesy of Republic Pictures in the next seven years, all of them outsourcing groundwork of the invasion to local muscle: Flying Disc Man from Mars (1951), Radar Men from the Moon and Zombies of the Stratosphere (both ’52), all three featuring stock footage from Purple Monster and other Republic serials. Maybe we’ll see one or more of those at future Picture Shows.

The final day of Columbus Moving Picture Show 2023 opened, naturally enough, with the final four chapters of The Purple Monster Strikes. Our slow-on-the-uptake hero, slugging-and-shooting attorney Craig Foster (Dennis Moore) finally begins to catch on that something’s not right with “Dr. Layton” (who is in fact the Purple Monster, having murdered Dr. Layton and taken over his body). Back in Chapter 11 the Emperor of Mars sent a female underling to assist the Purple Monster by killing one of the secretaries at the “jet plane” factory and taking over her body. By the way, oddly enough, when the Purple Monster arrives on Earth, he tells his hired Earthling thug, “My name would mean nothing to you; you can call me the Purple Monster.” But the female sent to aid him is named Marcia before she takes over the body of Helen. Do only women on Mars have simple names? Or is “Marcia the Martian” an alias? If so, why didn’t the Purple Monster just call himself “Martin”, like Ray Walston on 1960s TV? Then again, Martin Strikes wouldn’t have been a very dramatic title. Well, anyhow, Marcia was a little sloppy while vacating Helen’s body, and the late Dr. Layton’s niece Sheila (Linda Stirling), feigning unconsciousness, observed her in the act. This enabled Foster finally to put two and two together and plant a camera in “Dr. Layton’s” office to see if he’s doing the same thing. But even before the film is developed, the Purple Monster makes his move, absconding with the prototype “jet plane” to be reverse-engineered back on Mars. Fortunately, Foster turns the “annihilator ray” on the escaping Purple Monster and blows him out of the sky (another nifty miniature by the Lydecker Brothers). And Chapter 15 ends with the unspoken hope that future extraterrestrial invaders will be no smarter than this one was. There would in fact be three more such invasions courtesy of Republic Pictures in the next seven years, all of them outsourcing groundwork of the invasion to local muscle: Flying Disc Man from Mars (1951), Radar Men from the Moon and Zombies of the Stratosphere (both ’52), all three featuring stock footage from Purple Monster and other Republic serials. Maybe we’ll see one or more of those at future Picture Shows.

The Unknown Soldier (1926) was one of the rash of movies about the World War (they didn’t know yet that they’d have to give them numbers) that came out during the second half of the 1920s, and which would culminate in Universal’s All Quiet on the Western Front in 1930. It was independently produced by Charles R. Rogers for Producers Distributing Corp. (PDC — not to be confused with PRC, the rock-bottom Poverty Row studio Producers Releasing Corp.) PDC was a short-lived concern that would be merged with and absorbed by other little fish, eventually to coalesce into RKO Radio Pictures. In the meantime, PDC turned out a hundred or so pictures between 1923 and ’27, their most significant asset being Cecil B. DeMille during his brief estrangement from Paramount Pictures (though only one of DeMille’s PDC pictures, 1927’s The King of Kings, actually turned a profit).

The Unknown Soldier (1926) was one of the rash of movies about the World War (they didn’t know yet that they’d have to give them numbers) that came out during the second half of the 1920s, and which would culminate in Universal’s All Quiet on the Western Front in 1930. It was independently produced by Charles R. Rogers for Producers Distributing Corp. (PDC — not to be confused with PRC, the rock-bottom Poverty Row studio Producers Releasing Corp.) PDC was a short-lived concern that would be merged with and absorbed by other little fish, eventually to coalesce into RKO Radio Pictures. In the meantime, PDC turned out a hundred or so pictures between 1923 and ’27, their most significant asset being Cecil B. DeMille during his brief estrangement from Paramount Pictures (though only one of DeMille’s PDC pictures, 1927’s The King of Kings, actually turned a profit).

The Unknown Soldier told the story of a romance between Fred, a young worker (Charles Emmett Mack) and Mary, the boss’s daughter (Marguerite de la Motte) in defiance of her disapproving father (Henry B. Walthall, expressively stoic as ever). When America enters the Great War, they both enlist, he in the army, she in a troupe providing entertainment for the boys at the front. Reunited in France, they are married by a military chaplain before Fred’s unit moves up to the trenches. Simultaneously with learning she is pregnant, Mary also learns that the “chaplain” who married them was a deserter in disguise, and they’re not married after all. Hoping to set things right, Fred volunteers for a dangerous mission to find a lost patrol and escort them back to the town where he knows Mary and their child are recuperating from the baby’s birth. The patrol makes it to safety, but Fred goes MIA. Back home in the States, papa Walthall tells Mary she is welcome, but not her “illegitimate” child; she in turn tells him — in decorous silent-movie-intertitle euphemism — to go to hell.

Years pass. The remains of America’s first Unknown Soldier have been returned from France and are being conveyed in solemn procession to a resting place at Arlington (“Here rests in honored glory an American soldier known but to God”). In the crowd silently lining the route of the procession, father, daughter and grandchild (brought together by Mary’s aunt) are finally reconciled (their reunion cleverly intercut with newsreel footage of the actual 1921 procession). At this point, the implication is that the Unknown Soldier is in fact the missing Fred, killed on his mission to rescue the lost patrol, and now, in a strange twist of fate “known but to God”, bringing Mary, their child, and her father back together at last. This poignant dénouement appears to have been the original intent of director Renaud Hoffman and writers E. Richard Schayer and James J. Tynan. However, the producers hedged their bets by shooting an alternate ending in which Fred survives, albeit blinded and suffering from amnesia, until he regains his memory (though not his sight) in time for a tearful family reunion. PDC then offered exhibitors their choice as to which resolution they preferred. Sources differ as to which ending was more popular, but it was the “happy” ending that screened in Columbus. Obviously, this pretty much blows the whole point of calling the picture The Unknown Soldier in the first place. Without that original poignancy, the picture is basically warmed-over The Big Parade — not bad, some good moments, but nothing special, and redolent of its betters: Big Parade, What Price Glory?, Wings, Lilac Time, All Quiet, etc.

At this point — in the home stretch, as it were, and within sight of the finish line — The Picture Show was hit by a one-two punch of bad luck: The next two features on the program had to be replaced by unscheduled substitutes. First to go was I Can’t Give You Anything But Love, Baby (1940), a Universal B-musical starring Broderick Crawford as a gangster with songwriting ambitions who kidnaps a young composer to collaborate with. I have a soft spot for Classic Era B-musicals, and for Broderick Crawford in the days when he still looked like his mother Helen Broderick, but the print arrived with an advanced case of vinegar syndrome (a “disease” that can reduce an acetate-based print to a pile of warped, brittle substance reeking of salad dressing) and had been rendered unusable. I was disappointed, but then again Clive Hirschhorn’s The Hollywood Musical dismisses the picture as “61 ludicrous minutes of non-entertainment”, so maybe we dodged a bullet. In any case, the substitute was Twelve Crowded Hours (1939), and no complaints there.

At this point — in the home stretch, as it were, and within sight of the finish line — The Picture Show was hit by a one-two punch of bad luck: The next two features on the program had to be replaced by unscheduled substitutes. First to go was I Can’t Give You Anything But Love, Baby (1940), a Universal B-musical starring Broderick Crawford as a gangster with songwriting ambitions who kidnaps a young composer to collaborate with. I have a soft spot for Classic Era B-musicals, and for Broderick Crawford in the days when he still looked like his mother Helen Broderick, but the print arrived with an advanced case of vinegar syndrome (a “disease” that can reduce an acetate-based print to a pile of warped, brittle substance reeking of salad dressing) and had been rendered unusable. I was disappointed, but then again Clive Hirschhorn’s The Hollywood Musical dismisses the picture as “61 ludicrous minutes of non-entertainment”, so maybe we dodged a bullet. In any case, the substitute was Twelve Crowded Hours (1939), and no complaints there.

Twelve Crowded Hours — to use a line I can’t believe some reviewer didn’t use at the time — was 64 very crowded minutes. With beefy Richard Dix stuffed into a fast-talking-reporter role written for Lee Tracy, trying to clear his girlfriend Lucille Ball’s hapless brother (Allan Lane) of a murder rap, while nailing a numbers-racket kingpin (Cyrus W. Kendall) who keeps a truck-driver hit-man on retainer (he dispatches his marks by ramming their cars with his truck, which seems pretty inefficient, but we’re not given time to think about it) — anyhow, with all that, plus Donald MacBride playing one of his signature exasperated police detectives, director Lew Landers had a pretty busy juggling act on his hands, but he was up to it.

The other movie we were supposed to see but didn’t was Junior Miss (1945), from 20th Century Fox, adapted from the 1941 Broadway hit which was, in turn, based on a collection of New Yorker short stories by Sally (Meet Me in St. Louis) Benson. The picture starred the remarkable Peggy Ann Garner in a role as old as Jane Austen’s Emma and as recent as any movie starring Deanna Durbin: the mischievous teenage girl playing cupid for those around her. The movie looked promising, and Peggy Ann is always welcome, but it was not to be. Like I Can’t Give You Anything But Love, Baby, the Picture Show’s print of Junior Miss (whether due to vinegar syndrome or some other cause) was not eligible for running through a projector.

Instead we got Banjo (1947), a girl-and-her-dog B-movie starring ten-year-old Sharyn Moffett. Young Ms. Moffett was an appealing child actress who might have developed into the kind of juvenile star who justified the above-the-title billing she receives here. Unfortunately, at RKO (where the precarious studio administration always seemed to have more important things on their minds than grooming contract talent), she never had the kind of infrastructure that had served Peggy Ann Garner (and before her Shirley Temple) so well at 20th Century Fox. Today Sharyn Moffett is best remembered as the wheelchair-bound child who sets the plot in motion in Val Lewton’s The Body Snatcher (1945), and as Cary Grant and Myrna Loy’s younger daughter in Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House (’48).

Instead we got Banjo (1947), a girl-and-her-dog B-movie starring ten-year-old Sharyn Moffett. Young Ms. Moffett was an appealing child actress who might have developed into the kind of juvenile star who justified the above-the-title billing she receives here. Unfortunately, at RKO (where the precarious studio administration always seemed to have more important things on their minds than grooming contract talent), she never had the kind of infrastructure that had served Peggy Ann Garner (and before her Shirley Temple) so well at 20th Century Fox. Today Sharyn Moffett is best remembered as the wheelchair-bound child who sets the plot in motion in Val Lewton’s The Body Snatcher (1945), and as Cary Grant and Myrna Loy’s younger daughter in Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House (’48).

In Banjo young Sharyn plays Pat, a girl happily living with her widowed father and her dog Banjo on their prosperous Georgia farm. When her father is killed in a horseback riding accident, Pat is sent to live with her only relative, her wealthy aunt Elizabeth (Jacqueline White), who is living a carefree, self-centered life in Boston. There’s scarcely room in her life for a child (she’s not pleased that her trip to Bermuda must be canceled because of the girl’s arrival), and none at all for a dog. Banjo is banished to a pen in the backyard, but the pen can’t contain him, despite the ever-rising fence around it. Pat tries to please her aunt and keep Banjo with her, in which effort her only ally is a local doctor (Walter Reed), who happens also to be Aunt Elizabeth’s discarded fiancé — which prompts Pat also to try bringing her aunt and the doctor back together. Things at last come to a head: Banjo is banished again, this time all the way back to Georgia; Pat runs away to be with him, and…well, you can probably guess the rest.

Banjo is a pleasant specimen of heartwarming family entertainment, interesting not only for Sharyn Moffett, who shows she can carry a whole movie on her own small shoulders, but as only the second feature from prolific director Richard Fleischer (whose first, Child of Divorce, had also starred Sharyn Moffett). Another asset is Jacqueline White, whose innate appeal makes her likable even when Aunt Elizabeth is being most selfish and unreasonable. She is remembered today for another Richard Fleischer picture, the 1952 film noir classic The Narrow Margin, in which she played a train passenger with a secret. (And by the way, I’m pleased to report that at this writing, Ms. White is happily still with us. If her long life continues — and we should all hope it does — she will turn 101 on November 23, 2023.)

The day and the weekend wound up with Down to Earth (1917), one of Douglas Fairbanks’s pre-swashbuckling athletic/romantic comedies. O.M. Samuel’s review in Variety (Oct. 10, 1917) hailed it as Doug’s best picture to date (for a little perspective, Down to Earth was the star’s 18th feature; there would be 28 more, four of them talkies, before his screen career ended in 1937). Wherever the picture belongs in Doug’s filmography (my experience of his pre-Mark of Zorro work is not exhaustive), it’s certainly a pip. Doug plays an outgoing, hail-fellow-well-met type whose lifelong sweetheart Eileen (Ethel Forsythe) turns him down for a high-society cad (Charles K. Gerrard). But that fellow’s fast living brings on a nervous breakdown in Eileen, landing her in a sanitarium for wealthy hypochondriacs. That’s when Doug swings into action. Using a bogus smallpox scare, he spirits Eileen and her fellow inmates away to what he says is a desert island, where he sets about curing them all of their largely psychosomatic ailments while teaching them the benefits of exercise, a healthy diet, and good clean living. The story was Fairbanks’s own, worked into a scenario by him, Anita Loos, and Loos’s husband John Emerson (who also directed at the kind of pace Fairbanks loved to set). The cinematographer was the great Victor Fleming, who would go on to a stellar directing career himself, modeling his own manly persona on the star who gave him his start in pictures, and whom he so greatly admired.

The day and the weekend wound up with Down to Earth (1917), one of Douglas Fairbanks’s pre-swashbuckling athletic/romantic comedies. O.M. Samuel’s review in Variety (Oct. 10, 1917) hailed it as Doug’s best picture to date (for a little perspective, Down to Earth was the star’s 18th feature; there would be 28 more, four of them talkies, before his screen career ended in 1937). Wherever the picture belongs in Doug’s filmography (my experience of his pre-Mark of Zorro work is not exhaustive), it’s certainly a pip. Doug plays an outgoing, hail-fellow-well-met type whose lifelong sweetheart Eileen (Ethel Forsythe) turns him down for a high-society cad (Charles K. Gerrard). But that fellow’s fast living brings on a nervous breakdown in Eileen, landing her in a sanitarium for wealthy hypochondriacs. That’s when Doug swings into action. Using a bogus smallpox scare, he spirits Eileen and her fellow inmates away to what he says is a desert island, where he sets about curing them all of their largely psychosomatic ailments while teaching them the benefits of exercise, a healthy diet, and good clean living. The story was Fairbanks’s own, worked into a scenario by him, Anita Loos, and Loos’s husband John Emerson (who also directed at the kind of pace Fairbanks loved to set). The cinematographer was the great Victor Fleming, who would go on to a stellar directing career himself, modeling his own manly persona on the star who gave him his start in pictures, and whom he so greatly admired.

And with that, 2023’s edition of The Columbus Moving Picture Show rolled to a close. As always, I urge my readers to visit The Picture Show’s site at the link, get on their mailing list if you’re not there already, and give serious thought to joining us next Memorial Day. If you do, don’t forget to say hi.