Picture Show 02 — Day 2

(NOTE: Apologies for the longer-than-intended hiatus in my coverage of the Columbus Moving Picture Show 2023. Some issues arose with Cinedrome, something about the renewal of my SSL certificate; the site was knocked out for a while and I wasn’t even able to access the site to work on it. After three times contacting tech support at GoDaddy.com, my Web host, the issue seems to be resolved and I can resume coverage. I won’t go into detail about what the issue was — partly because it’s boring, and partly because I never did understand exactly what the problem was, and still don’t. Anyhow, the matter seems to be behind us — at least until my SSL certificate comes up for renewal again in August 2024. I’ll keep my fingers crossed about that.)

Day 2 of the Picture Show began with Chapters 4-7 of The Purple Monster Strikes, with Sheila and Craig — along with various bystanders, some of them ill-fated — being subjected at regular intervals to all the cliffhanger menaces six writers can concoct: an acid pit, an “Annihilator Beam”, a house booby-trapped with TNT, a truck laden with volatile rocket fuel. I think my favorite was Sheila’s peril at the end of Chapter 6, when she drops through a trapdoor in front of a scientist’s desk into a small pit that quickly fills up with water as the trapdoor closes again — an amenity presumably installed on the chance that the scientist might someday want to drown some visitors to his lab.

Bob Bloom’s notes tell us that Purple Monster was shot at a cost of $183,803, having run 14.8 percent over its budget of $160,057. Considering that the serial’s 15 chapters run a total of 201 minutes, that means Republic Pictures shelled out $914.44 per minute of screen time. (Never let it be said that Republic didn’t know how to get bang for their buck — literally.) Consider also that, correcting for inflation, Purple Monster‘s price tag in 1945 is the equivalent of $3,105,525.28 in 2023 dollars. By contrast, the latest adventure of Indiana Jones (the spiritual offspring of these Republic serials) cost $294.7 million, and it’s 47 minutes shorter. That comes to just a bit over $1.9 million per minute. Of course, there’s really no comparison. Although I guess I just made one.

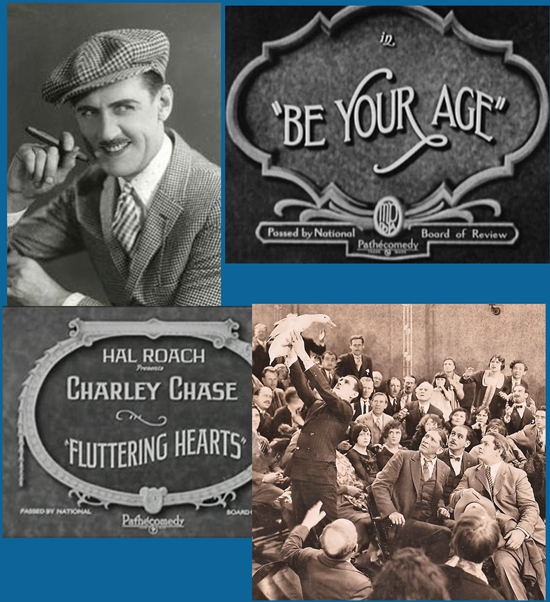

This was followed by a program of three Charley Chase silent shorts, a Columbus tradition going back a goodly number of years. Charley Chase’s shorts, silent and sound both, are always funny, but with this particular trio the moments of laugh-out-loud hilarity seemed to me particularly plentiful:

This was followed by a program of three Charley Chase silent shorts, a Columbus tradition going back a goodly number of years. Charley Chase’s shorts, silent and sound both, are always funny, but with this particular trio the moments of laugh-out-loud hilarity seemed to me particularly plentiful:

Be Your Age (1926) Bank clerk Charley gets a letter from home pleading for money (“My dear Charley – You must get $10,000 for us at once. Father broke his leg trying to put out the fire … The cook started the fire after she had shot Uncle Wilbur for choking Aunt Mollie … Aunt Mollie had gone mad from a dog bite and was trying to poison the children …”). Charley’s boss may have the solution: A multi-millionaire widow is looking to remarry, and the boss wants Charley to wed the old girl and persuade her to keep her fortune with the bank. Complicating things is that the widow’s son (a pre-Laurel Oliver Hardy) has a suspicious eye for fortune hunters — plus, Charley’s heart isn’t really in it, he being more attracted to the widow’s saucy young secretary. The timeworn phrase is “hilarity ensues”, and it does.

Fluttering Hearts (1927) Wealthy papa William Burgess wants daughter Martha Sleeper to marry a rich self-made man rather than the fortune-hunting “lounge lizards” who pursue her. Charley is just the kind of go-getter Papa wants for her, but she doesn’t know that when they meet and take a shine to each other, so she wangles him a job as the family chauffeur. Like many two-reelers, the action divides neatly into halves. Part One features Charley, Martha and cop Eugene Pallette doing battle with a mob of female shoppers at a linen sale. Then Papa is blackmailed over a compromising letter he once wrote to a showgirl, and Part Two follows Charley into a speakeasy with a mannequin (men can’t enter unless accompanied by a lady and that’s the best he can do), where he tries to retrieve the incriminating missive from the blackmailer (Oliver Hardy again). A highlight of this one is Charley’s long dalliance with the mannequin, a very funny riff that might have inspired Donald O’Connor’s “Make ‘Em Laugh” in Singin’ in the Rain if he’d seen it (he probably didn’t; he was only two in 1927).

Movie Night (1929) The title says it all, as Charley and his family (wife Eugenia Gilbert, daughter Edith Fellows and brother-in-law Spec O’Donnell) encounter comic obstacles that moviegoers from any era can recognize — at least until the manager brings up the lights for the evening’s prize drawing, a staple of movie houses that vanished decades ago. The prizes, what we see of them, are an odd lot (“A ham for Mrs. Ginsberg!”), culminating in a live duck for Charley. When Charley and his wife and daughter are ejected for disrupting the show (a glimpse of a poster tells us they missed A Woman of Affairs with Greta Garbo and John Gilbert; brother-in-law Spec is apparently allowed to stay), the duck provides them with an egg to pelt the manager with. Five-year-old Edith Fellows, making her film debut as Charley’s hiccuping daughter, went on to a surprisingly durable career spanning movies, TV and Broadway and extending into the 1990s, including movies with Jackie Coogan, Marie Dressler, Laurel and Hardy, Edna May Oliver, Lionel Barrymore, W.C. Fields, Eddie Cantor, Paul Muni, Claudette Colbert, Melvyn Douglas, Mary Astor, Bing Crosby, Gene Autry, the Five Little Peppers and How They Grew series at Columbia, and guest shots on Simon & Simon, St. Elsewhere, Scarecrow and Mrs. King, Cagney & Lacey, and ER. She died in 2011 at the Motion Picture Home in Woodland Hills, Calif., age 88. Did anybody interview this woman before it was too late?

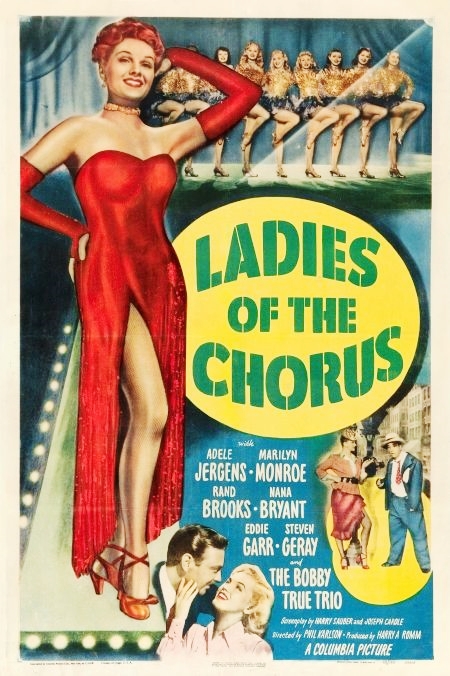

Film musical authority and historian Richard Barrios (A Song in the Dark, Dangerous Rhythm, Must-See Musicals, etc.) introduced Ladies of the Chorus (1948), a likeable, unpretentious B-musical from Columbia. Likeable, unpretentious B-musicals have been stock-in-trade at Cinevent and The Picture Show for decades; this one is particularly memorable because, like The Heart of Texas Ryan on Day 1, it had the good fortune to include a future superstar in the cast: in this case, Marilyn Monroe, second-billed to Adele Jergens and pretty clearly going places. Also like Texas Ryan, Ladies would be reissued a few years later with Marilyn promoted to the name above (and larger than) the title. I picked up a DVD in the dealers’ room from one of those reissues, bellowing “MARILYN MONROE in…” before the main title, but the print in the screening room was from 1948, where the credits ran as they do on this poster. The plot was a wispy thing: Adele and Marilyn are mother-and-daughter chorus girls in the most wholesome burlesque show in America, where not so much as a glove is ever taken off (though at one point Marilyn does toss a bracelet into the audience). Marilyn falls for rich scion Rand Brooks, which alarms Mama Adele, who remembers her own failed marriage to a wealthy Bostonian, when his horrified family drove her away and annulled the marriage before she learned she was pregnant. (Why she didn’t sue for child support, or at least hush money, is never explored; after all, we’ve only got 61 minutes and have to move on.)

Film musical authority and historian Richard Barrios (A Song in the Dark, Dangerous Rhythm, Must-See Musicals, etc.) introduced Ladies of the Chorus (1948), a likeable, unpretentious B-musical from Columbia. Likeable, unpretentious B-musicals have been stock-in-trade at Cinevent and The Picture Show for decades; this one is particularly memorable because, like The Heart of Texas Ryan on Day 1, it had the good fortune to include a future superstar in the cast: in this case, Marilyn Monroe, second-billed to Adele Jergens and pretty clearly going places. Also like Texas Ryan, Ladies would be reissued a few years later with Marilyn promoted to the name above (and larger than) the title. I picked up a DVD in the dealers’ room from one of those reissues, bellowing “MARILYN MONROE in…” before the main title, but the print in the screening room was from 1948, where the credits ran as they do on this poster. The plot was a wispy thing: Adele and Marilyn are mother-and-daughter chorus girls in the most wholesome burlesque show in America, where not so much as a glove is ever taken off (though at one point Marilyn does toss a bracelet into the audience). Marilyn falls for rich scion Rand Brooks, which alarms Mama Adele, who remembers her own failed marriage to a wealthy Bostonian, when his horrified family drove her away and annulled the marriage before she learned she was pregnant. (Why she didn’t sue for child support, or at least hush money, is never explored; after all, we’ve only got 61 minutes and have to move on.)

Everything works out for Marilyn and Rand, naturally, and Rand’s mother (Nana Bryant) shows she’s a good sight more salt-of-the-earth than those Boston snobs who high-hatted Adele. In the meantime, director Phil Karlson keeps things moving at a moderate gallop, and the musical numbers are fun. The songs by Alan Roberts and Lester Lee may not boast any deathless standards, but they’re catchy and clever; frankly, there have been Oscars handed out (and, truth to tell, Tonys and Pulitzer Prizes) for worse songs than these. As if Roberts, Lee, and Columbia could see the future, Marilyn gets two of the best and sells them well: “Anyone Can See I Love You”, in which she urges Rand Brooks to take a chorus, and he proves he literally can’t sing a note; and “Every Baby Needs a Da-Da-Daddy”, a sassy blend of “My Heart Belongs to Daddy” and “Put the Blame on Mame” (which Alan Roberts wrote with Doris Fisher for Gilda two years earlier). Adele Jergens has a solo too, in a flashback to her ill-fated courtship, presciently titled “Crazy for You”. Richard Barrios’s notes tell us her vocal was dubbed by Virginia Rees, and while she gamely prances her way through the dance break, it seems clear that her taps were dubbed as well as her voice. For the rest, it’s ensemble numbers by the eponymous ladies of the chorus, veteran matron Nana Bryant proving her salt-of-the-earth-ness by warbling “You’re Never Too Old to Do What You Did”, and an indescribable specialty, “The Ubangi Love Song”, by something called The Bobby True Trio.

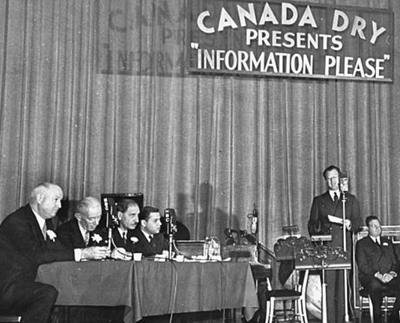

A novelty on the day’s program was a brace of Information Please shorts from 1941. Information Please (1938-51) was a radio quiz show with a twist: The contestants didn’t answer questions, they asked them. Listeners would mail in questions, often in two, three, or four parts, to be put to a panel of four experts. If their question was used on the air they would get a small cash prize, a larger one if they managed to stump the panel. Over the years the prizes varied as the show acquired different sponsors with different levels of generosity, eventually including an Encyclopædia Britannica and a $50 savings bond. The show was moderated by editor, writer and intellectual Clifton Fadiman, and the regular panelists were newspaper columnists John Kieran and Franklin P. Adams and composer/pianist Oscar Levant. (All were famous at the time for their expertise in what would one day be called “Trivia”; Kieran and Adams are largely forgotten today, while Levant remains fairly well-known thanks to his film career in such classics as Rhapsody in Blue, Romance on the High Seas, The Barkleys of Broadway, An American in Paris and The Band Wagon.) The fourth seat on the panel was taken by a different celebrity guest each week.

A novelty on the day’s program was a brace of Information Please shorts from 1941. Information Please (1938-51) was a radio quiz show with a twist: The contestants didn’t answer questions, they asked them. Listeners would mail in questions, often in two, three, or four parts, to be put to a panel of four experts. If their question was used on the air they would get a small cash prize, a larger one if they managed to stump the panel. Over the years the prizes varied as the show acquired different sponsors with different levels of generosity, eventually including an Encyclopædia Britannica and a $50 savings bond. The show was moderated by editor, writer and intellectual Clifton Fadiman, and the regular panelists were newspaper columnists John Kieran and Franklin P. Adams and composer/pianist Oscar Levant. (All were famous at the time for their expertise in what would one day be called “Trivia”; Kieran and Adams are largely forgotten today, while Levant remains fairly well-known thanks to his film career in such classics as Rhapsody in Blue, Romance on the High Seas, The Barkleys of Broadway, An American in Paris and The Band Wagon.) The fourth seat on the panel was taken by a different celebrity guest each week.

So popular was the show that RKO Radio filmed a number of broadcasts and released edited versions to theaters between 1939 and ’43, and a program of those was what followed after the Friday lunch break. The celebrity guests on display were the sociopolitical journalist John Gunther, and Howard Lindsay, the co-author and star of the long-running Broadway hit Life With Father. The Picture Show program book promised a third specimen with Guest Expert Boris Karloff, but that one, regrettably, was a no-show (it would have been fun to hear Karloff answer some questions about cricket, his spare-time passion). Still, the two we did get were fun, an authentic glimpse of radio-era programming that put me in mind of the quiz show Dianne Wiest wins in Woody Allen’s Radio Days (1987).

Gary Cooper and Mary Brian headlined Only the Brave (1930), following up on their teaming in Paramount’s big hit The Virginian from the year before. Reading reviews in Variety (Mar. 12, ’30) and the New York Times (Mar. 6, ’30) you’d hardly guess it, but John McElwee’s program notes and director Frank Tuttle’s posthumously-published autobiography make it clear that Only the Brave is a comedy, a deadpan parody of Secret Service by the 19th century actor-manager William Gillette. (Gillette, considered a national treasure in his day, is best remembered today as the first Sherlock Holmes of stage [1899] and film [1916]. His 1916 film was believed lost for over 90 years, until a print surfaced in 2014. That print, restored and enhanced, is available in a superb Blu-ray/DVD combo from Amazon, and well worth it. Gillette’s subtle, low-key style of acting was ideal for film; a pity this was his only one.)

Gary Cooper and Mary Brian headlined Only the Brave (1930), following up on their teaming in Paramount’s big hit The Virginian from the year before. Reading reviews in Variety (Mar. 12, ’30) and the New York Times (Mar. 6, ’30) you’d hardly guess it, but John McElwee’s program notes and director Frank Tuttle’s posthumously-published autobiography make it clear that Only the Brave is a comedy, a deadpan parody of Secret Service by the 19th century actor-manager William Gillette. (Gillette, considered a national treasure in his day, is best remembered today as the first Sherlock Holmes of stage [1899] and film [1916]. His 1916 film was believed lost for over 90 years, until a print surfaced in 2014. That print, restored and enhanced, is available in a superb Blu-ray/DVD combo from Amazon, and well worth it. Gillette’s subtle, low-key style of acting was ideal for film; a pity this was his only one.)

But back to Only the Brave. Don’t get your hopes up because of this exquisitely colored production photo; like almost every 1930 movie, it’s in black and white — and even the best 1930 Technicolor couldn’t duplicate this. Gary Cooper plays Capt. James Braydon, a Union officer during the Civil War who, home on surprise leave, finds his sweetheart (Virginia Bruce, incredibly young, almost unrecognizable) in the arms of another man. Heartbroken, he volunteers for an undercover suicide mission: He’s to infiltrate the South disguised as a Confederate officer, then be unmasked as a spy carrying papers about Union troop deployments — false papers, in a disinformation action to lure the Rebels into a trap. He’ll be condemned to hanging or a firing squad, but he no longer cares. That is, until he meets southern belle Mary Brian, daughter of his Confederate general host. She falls in love with him and, every time he tries to get himself exposed and arrested, she contrives to save and protect him. Finally he manages to foil her interference and get himself sent to a firing squad — but all ends well when the Yankees ride to the rescue, Lee surrenders at Appomattox, and our hero goes not to the firing squad but to the altar with the heroine.

Reviewers at the time remarked on how moth-eaten the story of Only the Brave was, the spoof evidently going right over their heads. Well, that’s the chance you take when your comedy is too subtle. They even compared it to Gillette’s old melodrama Secret Service, wherein (as well) a Union spy becomes romantically involved with an unsuspecting Confederate belle. But that’s the beauty of Only the Brave: You can take it as straight melodrama or as a wry send-up; either way, at 71 minutes it doesn’t wear out its welcome, and Cooper and Brian really do make a beautiful pair. (A year later, RKO would manage to wring a little more mileage out of Secret Service, with Richard Dix and Shirley Grey as the war-torn lovers, playing it straight.)

In 1969 the Museum of Modern Art mounted an exhibition, “Stills from Lost Films” curated by Gary Carey, drawing on the museum’s vast photo archive, contemporary reviews, and archival publicity materials to try to capture the essence of movies that no longer existed. In 1970 Carey turned the exhibition into a book encompassing 30 titles — most from the exhibition, with a few substituted “for personal reasons”, and at least one, Benjamin Christensen’s The Devil’s Circus (1928), being dropped because a print had turned up.

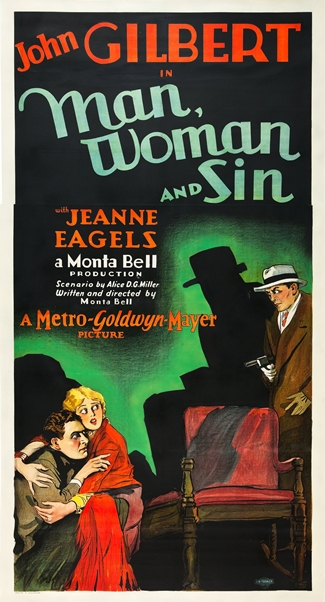

In the 53 years since Carey’s Lost Films was published, there has been more good news. Of the 30 titles Carey described, ten are no longer entirely lost. Three have surfaced here and there, albeit missing a reel or so; the other seven are all reasonably intact. One of the latter is Man,Woman and Sin (1927). This was a picture MGM produced to please their top star John Gilbert. Gilbert, who had ambitions beyond being a matinee-idol heartthrob, had brought the studio John Masefield’s long poem The Widow in the Bye Street and asked them to buy it for him.

Among the British, John Masefield (1878-1967) is noted for being second only to Alfred, Lord Tennyson as the United Kingdom’s longest-serving Poet Laureate (37 years, to Tennyson’s 42). Among Americans, however — at least those who went to high school when they still taught about poets — Masefield is most famous for “Sea Fever”, one of his shortest poems (“I must go down to the sea again, to the lonely sea and the sky,/And all I ask is tall ship and a star to steer her by…”). The Widow in the Bye Street, published in 1912 near the beginning of his writing career, tells of the widow Gurney, working day and night at menial jobs to raise her son Jimmy. Her sacrifice and protectiveness lead her to shelter her son from any contact with the female sex, with the unintended result that upon reaching the age of physical maturity he is emotionally immature and particularly susceptible to feminine charms. He falls for Anna, oblivious to the fact (though Mother tries to warn him) that she’s a local hooker being kept by Ern, a village shepherd and married man. When Ern exerts his right of “ownership” and sends the humiliated Jimmy packing, Jimmy’s life spirals off into drinking and dissipation. He loses his job, drinks more and more, until finally in a jealous drunken rage he seizes a farmer’s hand tool and attacks Ern, literally beating his brains out. From there, alas, it’s but a short trip to the gallows, leaving his mother to grieve and Anna to find another sugar daddy.

As Samantha Glasser points out in her program notes, Masefield’s poem was seriously sanitized on the way to the screen. The English village setting would never do, so the action was shifted to a Washington, DC newspaper. Factory worker Jimmy Gurney became cub reporter Albert Whitlock. The whore Anna morphed into the paper’s society editor Vera Worth (Jeanne Eagels), who was being kept not by some country shepherd but by the paper’s editor Bancroft (Marc McDermott). Anna/Vera was now more flirt than floozie, coming on to Albert to make Bancroft jealous. Albert still killed Bancroft, but exactly how wasn’t clear. (Whether this is due to poor staging and editing by director Monta Bell, or to the picture’s incomplete survival, is hard to tell at this distance in time.) In any case, Vera’s testimony at trial sends Albert to Death Row. Then, in response to the pleading of Albert’s mother (Gladys Brockwell), she recants her testimony, revealing that Bancroft’s death was a matter of self-defense. Albert is freed, to mosey home with his loving mother while Vera watches them leave the prison gates from the back seat of her chauffeured limousine.

Any lost film that turns up is cause for rejoicing, and so it is with Man, Woman and Sin. But all the “sanitizing” The Widow in the Bye Street underwent in its journey from verse to screen only served to homogenize it from a rough-hewn British working-class tragedy to a standard John Gilbert romantic melodrama, right down to the generic title change focusing on the lovers and shoving Mother aside. So much for Gilbert getting beyond the matinee-idol heartthrob label. In 1927 Man, Woman and Sin was dismissed as run-of-the-mill stuff, and it’s not hard to see why. Gilbert lays on the wide-eyed-gee-whiz routine pretty thick, and the Oedipal undertones to the story are borderline-alarming today, exacerbated by the fact (which age makeup can’t quite conceal) that Gladys Brockwell was less than three years older than her “son”. The picture’s main interest now is as an early glimpse of Jeanne Eagels, whose star quality comes across even in silence. Gilbert, Eagels and Brockwell, sadly, would all die before they were 40. In fact, after Man, Woman and Sin, Eagels and Brockwell had less than two years to live.

After the dinner break writer/director Michael Schlesinger gave a short presentation on his forthcoming comedy Rock and Doris (Try to) Write a Movie, an adaptation-cum-spoof of the old George M. Cohan chestnut Seven Keys to Baldpate (which was already a bit of a spoof, filmed at least seven times between 1916 and 1947). Schlesinger, a Cinevent/Picture Show regular already noted for his Biffle and Shooster shorts, looks to be putting his unique stamp on this new material. This was followed by a 25-minute program of Soundies. Soundies, introduced in 1941, were two-to-three-minute musical performances printed on 16mm and projected on translucent screens in refrigerator-size “Panoram” jukeboxes. James S. Petrillo’s American Federation of Musicians decreed that members could not perform live for these micro-musicals; they had to pantomime to pre-recorded playback tracks. This actually freed the makers of soundies to think outside the box and take their camera anywhere they pleased, which in turn made soundies sort of forerunners of the music videos of a later generation. The idea never really caught on for several reasons. For one thing, playing a single soundie cost ten cents, for which you could play two records on a regular jukebox. For another, you couldn’t choose what your dime would play; each machine had only eight soundies on an endless loop (changed weekly), and when you dropped your coin you just got whatever came up next. Finally (and perhaps most important), people didn’t play a jukebox so they could stand there staring at it; they wanted to dance — or at least get a little background music while they enjoyed their burger or ham-and-eggs at the diner. On top of all that, when the U.S. entered World War II the metal, wood and rubber used to build the Panoram machines became restricted to use for the war effort, and additional machines couldn’t be built. Fortunately, the various concerns involved in soundie production didn’t give up until 1946 or so, and hundreds of the films survive. The Picture Show presented an assortment of eight or ten, including one by a youthful Lawrence Welk and his orchestra, and another featuring a young pianist with a wide toothy grin billed as “Walter Liberace”.

After that it was Let’s Go Native (1930), a choppy, haphazard, truly bizarre early musical from Paramount. The basic premise: A struggling musical revue takes the show on the road, setting sail for Buenos Aires less to entertain Argentine audiences than to elude American bill collectors. Jeanette MacDonald, in her third picture, plays the show’s harried costume designer, romanced by rivals James Hall and David Newell, two actors so indistinguishable that if they weren’t in scenes together it’d be hard to believe they were two different men. Newell is the ship’s Chief Officer, Hall a poor little rich boy trying to untangle himself from fiancée Kay Francis. So Jeanette MacDonald is torn between Newell and Hall, Hall is torn between Jeanette and Kay Francis, and Kay is torn between Hall and Jack Oakie, as a cab driver who (never mind how) comes aboard first to stoke coal in the engine room, then to wait tables in the dining salon, accompanied by a silly-ass sidekick played by William Austin. Throw in a shipwreck that strands the company (and their costumes) on a tropic isle of nubile maidens ruled by Skeets Gallagher as their Brooklyn-born king (“I told you to bring us some ersters without poils!”). Then top it all off with an earthquake, a volcanic eruption, and the whole island sinking into the sea, and you’ll find yourself wondering if there’s anything this movie won’t toss in. (A good thing the atom bomb hadn’t been developed yet, or who knows how the picture would have wound up?)

After that it was Let’s Go Native (1930), a choppy, haphazard, truly bizarre early musical from Paramount. The basic premise: A struggling musical revue takes the show on the road, setting sail for Buenos Aires less to entertain Argentine audiences than to elude American bill collectors. Jeanette MacDonald, in her third picture, plays the show’s harried costume designer, romanced by rivals James Hall and David Newell, two actors so indistinguishable that if they weren’t in scenes together it’d be hard to believe they were two different men. Newell is the ship’s Chief Officer, Hall a poor little rich boy trying to untangle himself from fiancée Kay Francis. So Jeanette MacDonald is torn between Newell and Hall, Hall is torn between Jeanette and Kay Francis, and Kay is torn between Hall and Jack Oakie, as a cab driver who (never mind how) comes aboard first to stoke coal in the engine room, then to wait tables in the dining salon, accompanied by a silly-ass sidekick played by William Austin. Throw in a shipwreck that strands the company (and their costumes) on a tropic isle of nubile maidens ruled by Skeets Gallagher as their Brooklyn-born king (“I told you to bring us some ersters without poils!”). Then top it all off with an earthquake, a volcanic eruption, and the whole island sinking into the sea, and you’ll find yourself wondering if there’s anything this movie won’t toss in. (A good thing the atom bomb hadn’t been developed yet, or who knows how the picture would have wound up?)

Let’s Go Native is a mess, right enough — director Leo McCarey hasn’t yet got the hang of talking pictures, and he resorts often to bits remembered from his days at Hal Roach directing Charley Chase and Laurel and Hardy — but it’s rather fun in spite of itself. The songs by Richard Whiting and George Marion Jr. aren’t their best, but they’re not bad, and Oakie, MacDonald and two platoons of leggy Pre-Code chorines make the most of them. Jeanette MacDonald appears to have had few fond memories of the picture: In her autobiography (unpublished until 2004) she mentions it only twice, along the lines of “Then I did Let’s Go Native…” and “After Let’s Go Native I made…” Truth to tell, it was too many movies like this and not enough like The Love Parade, Jeanette’s first picture (or even Clara Bow’s Love Among the Millionaires from Paramount a month earlier) that killed musicals the first time around. Four years later, Paramount (having learned their lesson) would do much better with a similar plot (and a better cast: Bing Crosby, Carole Lombard, Ethel Merman, Burns and Allen, Leon Errol) in We’re Not Dressing. Still, Let’s Go Native has its pleasant surprises — among them hearing Kay Francis sing, and quite nicely, too.

The day wrapped up with Guilty Bystander (1950), a really nifty little noir thriller directed by Joseph Lerner for Laurel Films, a fly-by-night operation that, for a while, made movies on microscopic budgets wherever they could set up a camera without the cops chasing them away. Top-billed were Zachary Scott and Faye Emerson, occasional co-stars at Warner Bros., and both now on the down-slope of their careers. Scott, who had carved a niche for himself as Hollywood’s favorite pencil-neck lounge lizard, was ideally cast and gave one of his best performances — perhaps, indeed, his very best. He plays Max Thursday, a drunken ex-cop kicked off the force and reduced to working as house detective at a fleabag hotel in exchange for a room and drinking money. Suddenly his ex-wife Georgia (Emerson) barges into his shabby digs in a panic and drags him out of his alcohol haze — their son Jeff and her own ne’er-do-well brother have disappeared. Georgia has been warned not to go to the police, but she doesn’t know why they were taken, how she can get them back, or even if they’re still alive.

The day wrapped up with Guilty Bystander (1950), a really nifty little noir thriller directed by Joseph Lerner for Laurel Films, a fly-by-night operation that, for a while, made movies on microscopic budgets wherever they could set up a camera without the cops chasing them away. Top-billed were Zachary Scott and Faye Emerson, occasional co-stars at Warner Bros., and both now on the down-slope of their careers. Scott, who had carved a niche for himself as Hollywood’s favorite pencil-neck lounge lizard, was ideally cast and gave one of his best performances — perhaps, indeed, his very best. He plays Max Thursday, a drunken ex-cop kicked off the force and reduced to working as house detective at a fleabag hotel in exchange for a room and drinking money. Suddenly his ex-wife Georgia (Emerson) barges into his shabby digs in a panic and drags him out of his alcohol haze — their son Jeff and her own ne’er-do-well brother have disappeared. Georgia has been warned not to go to the police, but she doesn’t know why they were taken, how she can get them back, or even if they’re still alive.

Like all low-budget mysteries, Guilty Bystander suffers from the fact that there aren’t enough suspects on the producers’ payroll for the ending to be much of a surprise. Still, the movie is well-plotted, and the Big Reveal, when it comes, is satisfying. Performances are excellent all around; not only Scott and Emerson, but Mary Boland (one of Hollywood’s go-to ditzy matrons in the 1930s and ’40s) cast against type in, essentially, the Marie Dressler role as the boozy proprietor of Scott’s grubby hotel; Sam Levene as a friendly-for-old-times’-sake police captain; and J. Edward Bromberg as a small-time gang lord. Plus there were surprise early appearances by such future familiar faces as Dennis Patrick, Jesse White, John Marley and Maurice Gosfield (later Pvt. Doberman on Phil Silvers’ Sgt. Bilko TV series). All this, plus the brisk pace set by director Lerner and the seedy authenticity of the mean-street locations, added up to a compact, impressive little near-classic noir.

For Boland and Bromberg, Guilty Bystander proved the end of their worthy movie careers. Boland, 68 during shooting, retired to New York, where she died at 83 in 1965. Bromberg’s end came sooner and was more turbulent. A Group Theatre Communist during the 1930s, around the time Guilty Bystander was in production he took the Fifth in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee, hectoring them about their witch hunt. His defiance got him blacklisted and he decamped to England to work on the London stage. But it was too late; the stress had taken its toll and a heart attack took him off in December 1951, 19 days short of his 48th birthday.

And with the final resolution to Guilty Bystander‘s mystery, that was it for Day 2 of 2023’s Picture Show. Days 3 and 4 won’t be quite so long in coming.