Songs in the Light, Part 1

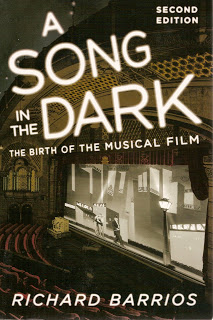

Richard Barrios’s A Song in the Dark: The Birth of the Musical Film has been one of the indispensible movie books ever since it came out in 1995. Now there’s a second edition and, no surprise, it’s just as indispensible as the first. Maybe more.

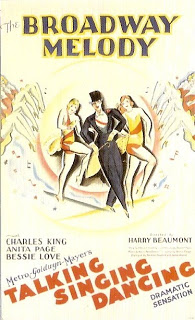

Barrios’s thesis was a bold one in ’95. Those early musicals, he said, weren’t simply the clumsy relics that time and advancing technique had made so embarrassing to look at today. (This may be the worst film ever to win a Best Picture Oscar sneered the L.A. Times, belittling The Broadway Melody several generations after the fact.) On the contrary, Barrios contended — and he proved his point beyond arguing — that they’re the precious record of an industry in turmoil, groping and struggling to invent a genre that had simply never existed before — and which in time would be viewed as the jewel in the crown of Golden Age Hollywood. And doing it all, moreover, not behind locked doors in secret trial-and-error experiments, but “in nearly full view of a vast, enthusiastic, and finally exasperated mass audience.” What is worth remembering about those early talkie-singie-dancies isn’t how primitive, naive and maladroit they look to us now, but how they electrified audiences at the time, and how much they still seem to get right — even if serendipity deserves the credit as often as deliberate intent.

Barrios says musicals were inevitable once sound came in, because they were the only thing silent movies couldn’t do. No doubt he’s exactly right; even Shakespeare, Oscar Wilde and La Boheme had been successfully filmed in the silent era; who’s to say that couldn’t have continued indefinitely? But say — what if it was the other way around? What if it was musicals that made sound inevitable? Seems to me that’s at least as valid a point as vice versa. Barrios doesn’t come right out and say so, and he may not have meant to imply it, but it occurred to me that maybe the popularity of musicals — at least for those crucial first two-or-three years, before they became a drug on the market and had to be resuscitated by Busby Berkeley at Warner Bros. and Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers at RKO — maybe that very popularity, at this delicate point when studios were teetering, trying to decide if sound was permanent or a passing fad, is the reason sound came in to stay. Surely it couldn’t have been because of Lights of New York (“Take him…for…a ride!“).

So did sound usher in musicals, or did musicals usher in sound? Chicken, egg. I don’t know; I guess you could argue either side of that one. The point is, I didn’t even think to frame the question before A Song in the Dark came along. That’s what makes it one of the indispensible books: it was a paradigm-shifter in 1995, and it still is. Once you’ve read it, you simply can’t look at those 1927-34 musicals the same way again. I’m grateful to Barrios for giving me a firm context for The Broadway Melody and saving me from making a public comment that’s as … well, let’s say “as lacking in nuance” … as the one quoted above from the L.A. Times.

Reading the second edition of ASITD, I get the distinct impression that it’s a substantially different book from the first one. (Alas, I lent out my first edition in 2004 and never got it back, so I can’t readily compare them side by side.) It’s an odd feeling, revisiting a book I remembered as just about perfect, and finding it distinctly different — yet, still, just about perfect.

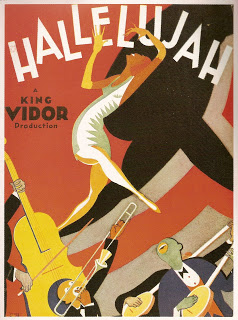

Whatever changes Barrios has made in his text, one thing’s definitely different this time around: I’ve been able to see a lot more of the movies he writes about. Back in ’95, I had (at least) vols. 1-3 of George Feltenstein’s Dawn of Sound laserdisc collections, so I could check out Broadway Melody, Hollywood Revue of 1929, Sally (with Queen of Broadway Marilyn Miller), and King Vidor’s pioneering all-black Hallelujah!; I could even confirm that Golden Dawn is every inch the ghastly cringe-making fiasco Barrios said it was (and that’ll be enought of that, thank you!). And in the clips and excerpts, I saw enough of delightful Dorothy McNulty galvanizing the gang into “The Varsity Drag” in 1930’s Good News to make me wish they’d release the whole movie — or what survives of it — on its own (are you listening, Warner Archive?).

Otherwise, pickings could be pretty slim. Take the case of Rouben Mamoulian’s masterpiece Love Me Tonight. “Let it be stated plainly:” Barrios said, then and now, “Love Me Tonight is a wonderful film, one of the two or three greatest musicals ever made.” Hooray and amen! No joke and no exaggeration. But if you

wanted to see it in 1995, you’d better have a collector friend who owned a print, or a connection at one of the big film archives. Fortunately for me, I had the former, so I knew whereof Barrios spoke. By 2001, I had managed to get my hands on a decent 16mm reduction print of my own. Then, two years later, Kino Video made my print obsolete by (finally!) issuing a sparkling new DVD transfer. It was worth the wait, but for a movie as delightful, as flawless, and as historically important as Love Me Tonight, it’s a pity we had to wait at all.

In 1997, Universal, owners of the pre-1948 Paramount library, issued The Lubitsch Touch, a laserdisc box set that included, for appetites whetted by Barrios’s first edition, several of director Ernst Lubitsch’s seminal early-sound musicals, long out of circulation: The Love Parade, Monte Carlo, One Hour with You, The Smiling Lieutenant. As good as it is to read Barrios on Jeanette MacDonald singing “Beyond the Blue Horizon” in Monte Carlo, there’s no substitute for the sublime pleasure of the real thing. Ideally, we should have both; we can now, but we couldn’t in 1995.

What with Turner Classic Movies, Netflix, the Warner Archive and the Universal Vault, I’ve been able to season my reading of Barrios’s second edition by seeing movies I could only have dreamed of fifteen years ago: Chasing Rainbows, It’s a Great Life, Flying High, Love in the Rough, So This Is College, Sunny, So Long Letty, Rio Rita (1929), Lord Byron of Broadway, On with the Show!, Sweet Kitty Bellairs. Even The Great Gabbo is waiting impatiently at the top of my Netflix queue. (Frankly, I’m rather dreading that one — overtly obnoxious, Barrios says — but hey, if I can take Golden Dawn I can take anything.) In fact, the seasoning goes both ways: reading about the movies enhances the experience of seeing them, while seeing them deepens my admiration for how well Barrios writes about them.

In Part 2, I’ll talk about some of these movies.