Songs in the Light, Part 2

Last time, when I talked about early-sound musicals being a “precious record of an industry in turmoil,” I didn’t mention the heartbreaking truth: the record is all too incomplete. We may have a more thorough sampling of the doodles of Leonardo Da Vinci than we do of movies made during the 1920s, and reading a roster of lost films can be like listening to the mournful tolling of a funeral bell: gone … gone … gone. Before talking about some of the movies mentioned in A Song in the Dark, I want to give a rueful nod to all the movie musicals made between 1927 and 1934 that neither I nor anyone else will ever be able to see.

Just for starters, there are My Man (1928) and Honky Tonk (1929), which might have given us a record of (respectively) Fanny Brice and Sophie Tucker in their primes. And The Rogue Song, starring the great Metropolitan Opera baritone Lawrence Tibbett. Tibbett, whom Barrios calls “simply one of the best voices ever captured on a soundtrack” (the Vitaphone discs for the movie survive), was nominated for an Oscar for Rogue Song, but we’ll probably never know why.

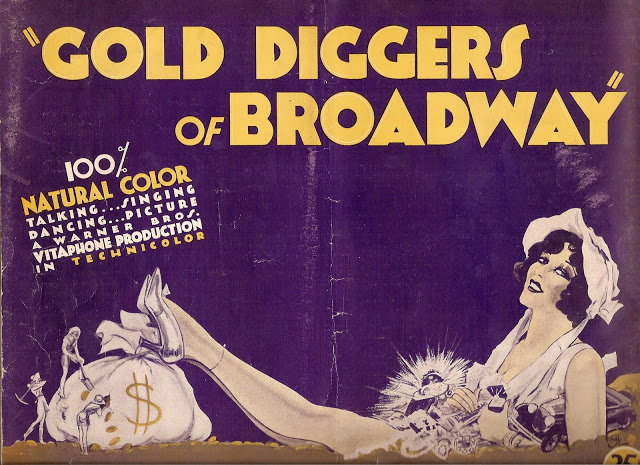

Let one particular movie stand in for all the ones we’ve lost. In his book The Hollywood Musical, Ethan Mordden awarded the title of “Most Tantalizing Lost Film” to:

What’s tantalizing is that it isn’t completely lost. Just enough has surfaced to show us why it was a blockbuster hit, raking in a then-stratospheric $4,000,000 at the box office and, like Broadway Melody, spawning a succession of follow-ups — not exactly sequels or remakes, but simply repetitions of that magic title: just as MGM gave us Broadway Melodys in 1936, ’38 and ’40, so Warner Bros. trotted out some Gold Diggers in 1933, ’35, ’37 and in Paris.

As for the remnants of Gold Diggers of Broadway. We have guitar-strumming troubadour Nick Lucas introducing one of the movie’s two big hit songs, “Tiptoe Through the Tulips” (the other hit, “Painting the Clouds with Sunshine,” survives only on the Vitaphone disc), and a few scattered seconds here and there. Best and most tantalizing of all, we have all but the last 60 seconds of the finale, a spectacular production number that seems to have recruited every dancer in California, including some acrobatic dancers — one girl, then two boys — whom I wish I could single out by name. Whoever you were, kids, and wherever you are, well done.

The two-strip Technicolor looks a little faded — apparently, Technicolor dyes didn’t yet have the rock-solid permanence they would attain later on, after Herbert Kalmus perfected the process — but the look of the number is still impressive.

Let me rephrase that. It looks impressive now; in 1929 it must have looked astounding.

These frames are from the preservation print. The original nitrate footage (safely squirreled away, I hope, in a climate-controlled vault) may look better; it appears that modern technology is incapable of duplicating the look of what little two-strip Technicolor survives (in 1970 I saw the only existing nitrate Tech print of 1933’s Mystery of the Wax Museum; no video version has come close to duplicating the delicacy of those colors).

Technicolor’s original contracts with the studios stipulated that the color negative elements would remain the sole property of Technicolor Inc., although positive prints might remain in studio hands. Then, somewhere along the line (Barrios says it was in the early 1950s), Technicolor decided that all those old reels were simply relics of an early, imperfect product — and a fire hazard to boot — so they systematically set about destroying them. I even heard once that they simply chartered a boat, chugged out past the three-mile limit, and dumped millions of feet of film history into the Pacific Ocean. I don’t know if that’s true, but the rumor alone is an emblem of the state of film preservation circa 1953. Thanks for nothing, Technicolor; your dog-in-the-manger attitude assured that any examples we have of two-strip Technicolor — like the first feature, Toll of the Sea (1922), Douglas Fairbanks’s The Black Pirate (1926) and Eddie Cantor’s Whoopee! (1930) — have survived by pure, blind accident.

One musical on which I understand the negative has in fact survived is Follow Thru (1930), from the DeSylva-Brown-Henderson Broadway hit that included “Button Up Your Overcoat” and “I Want to Be Bad.” Considering that two-strip Tech’s forte was in the green-to-orange-to-red range, what could be more natural than a musical set on a golf course? And the UCLA Film and Television Archive’s restoration print looks and sounds great — much better than it does in this YouTube clip of Zelma O’Neal and a troupe of angel/devils singing and dancing “I Want to Be Bad,” but it’ll give you a flavor of the fun to be had.

If you live in the vicinity of Palo Alto, Calif. and would like to see how this scene (and the rest of Follow Thru) really looks, that UCLA print will be playing at the Stanford Theatre in downtown P.A. at the end of this month (May 26-28). It’s a real crowd-pleaser and the Stanford brings it back periodically. On the bill with it will be Wake Up and Live with Alice Faye and Jack Haley; they’re both worth the trip.

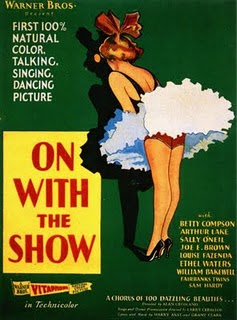

Others of these early Tech musicals survive in black and white, thanks to their sale to television in the late ’40s and early ’50s; b&w prints were struck off for broadcast and are now all that survives of them. I call these movies “half-lost,” but in fact it may be more than half. Case in point: On with the Show! (’29), an early backstage-clone of Metro’s Broadway Melody, and Warner Bros.’ first all-talking Technicolor musical. Harried producer Sam Hardy tries to hold his show together long enough to limp into New York for (hopefully) success on Broadway; along the way he contends with impatient creditors, bickering stars (Arthur Lake and Joe E. Brown), a temperamental leading lady (Betty Compson) and her sleazeball Lothario boyfriend (Wheeler Oakman) — and on top of all that, somebody robs the box office. The movie has its pleasures, including a persuasive backstage atmosphere, an engaging score, nifty comic dancing by Brown, and the great Ethel Waters (playing herself) introducing “Am I Blue?” and “Birmingham Bertha.” Liabilities too, chief among them shaky sound recording that renders much of the choral singing unintelligible, and befuddled little Sally O’Neil as the hat-check girl who becomes a star when the leading lady walks out. (Poor O’Neil had a winsome kewpie-doll face that made her a natural for silents, but a glass-scratching Noo Joizey twang that doomed her in talkies, starting here.)

How bad would those liabilities look today if we could see On with the Show! (a big $2.4-million hit) the way audiences did in 1929? No telling, but here’s a clue: on the left is a frame from a 30-second snippet of nitrate Technicolor footage that surfaced in 2005; beneath it is the same moment from the surviving b&w version, as it looked when broadcast on Turner Classic Movies in July 2009.

The color frame, remember, is nitrate stock, so there’s none of the color loss you’ll see in those frames from Gold Diggers or the Zelma O’Neal clip from Follow Thru. A glance from one frame to the other gives an inkling of what posterity lost when Technicolor decided its early work wasn’t worth bothering with. Of course, the glass is half full, too: if Warner Bros. hadn’t decided it was worth copying in b&w and selling to TV, we wouldn’t have On with the Show! at all.

I see I’m running a little long here, so I’ll close with another YouTube clip. I mentioned the “sublime pleasure” of Jeanette MacDonald singing “Beyond the Blue Horizon” in Monte Carlo. Well, here it is. Jeanette plays a runaway bride leaving her boring blueblooded twit of a fiance at the altar; she boards the train for Monaco convinced there must be something better than what she’s running away from. The clip is a ten-minute excerpt from Monte Carlo, but the money scene is the first 2 min. 36 sec. Between the driving locomotive rhythm and the soaring melody, there’s simply no getting this song out of your head. (UPDATE 9/1/16: Alas, that clip has gone dead now. Too bad, you don’t know what you’re missing; you’ll just have to track down Monte Carlo to find out. Meanwhile, if it surfaces again on YouTube I’ll include it here.)

Still more to say about these early musicals; I hope you’ll come back for Part 3.