“A Genial Hack,” Part 2: The Trail of the Lonesome Pine

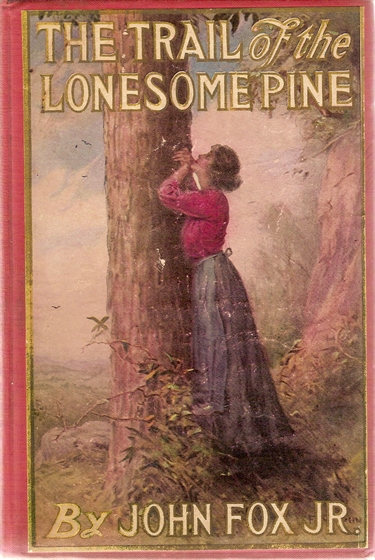

The book was a phenomenal success. Records being what they were in those days, it’s hard to know exactly how many copies it sold. Surely in the hundreds of thousands, probably more; one source I found said 1.3 million, at a time when a million-selling book was something to write home about. In any case, here’s what Fox’s novel looks like. It may look familiar; if you’ve spent any time at all in a used bookstore, you’ve probably seen several copies. They’re not uncommon, even after 102 years, and they’re not expensive; no telling how many times used copies like this one have been sold, resold, and resold again since 1908.

The novel has gone in and out of print (it’s currently in), but its popularity has never really gone away. In the wake of the 1936 movie, there was a stage adaptation that is still performed every summer (“official outdoor drama of the Commonwealth of Virginia”) in Big Stone Gap, Va., where Fox died in 1919. Fox managed somehow to come up with one of those perfect titles. Even if you’ve never heard of him or his books (and these days, most people outside Virginia and Kentucky haven’t), you feel as if you know what the story’s about the minute you hear it. The Trail of the Lonesome Pine — all by themselves, the words conjure up a time, a place, and a heart-on-the-sleeve sentimental romanticism.

The movie Hathaway and writer Grover Jones made for producer Walter Wanger in the late summer and early autumn of 1935 was the last, but not the first from Fox’s book; there had been three silent ones, in 1914, 1916 and 1923. There hasn’t been a movie from Fox’s novel since then. The reason could mainly be changes in public taste — romantic backwoods melodramas aren’t the surefire thing they were at the turn of the 20th century. But it could also be simply that the amazing success of Hathaway’s version — reinforced by numerous reissues over the next 20-plus years — made it an indelible act to follow.

The movie was a smash. It was only the second feature in Herbert Kalmus’s newly perfected three-strip Technicolor, and the first shot outdoors, in scenery made for Technicolor — Big Bear, in California’s San Bernardino Mountains. My mother saw The Trail of the Lonesome Pine as an 11-year-old girl, and she said her most vivid memory of it was Sylvia Sidney’s blue eyes. I know what she meant; I saw Lonesome Pine on a theatrical reissue when I was eight, and I remember Sylvia Sidney’s eyes just as clearly as my mother did. This frame from the Universal Home Video DVD release shows (to those of us who remember it in theaters) that it doesn’t do full justice to the IB Tech. But even to those who don’t remember it that way, it gives a powerful hint, and it’s a beautiful shot in its own right. It’s easy to believe that audiences in 1936 weren’t accustomed to seeing things like this on their movie screens.

Or this. Here’s the first sight that greeted audiences after the opening credits, and it suggests a canny calculation in the movie’s color scheme. Blue was one color that the old two-color system simply couldn’t handle; the closest it could come was a sort of turquoise. Even oceans and skies came out a sort of yellowish green. And the credit sequence to Lonesome Pine — names carved into tree trunks in a thick forest — seems almost deliberately weighted toward the red range that had been the old Tech’s long suit. It’s as if the credits are designed to invoke Your Father’s Technicolor, to remind you of what Technicolor couldn’t do just before showing you what it can do now. The effect, even now, is spectacular.

The first full-Technicolor feature, Rouben Mamoulian’s Becky Sharp, also made experiments with color, but it was setbound and stagy where Lonesome Pine was sun-splashed and outdoor-crisp. More to the point, Becky Sharp was a financial disappointment, if not a flop. People began to wonder if Technicolor could justify the extra expense. By the end of Lonesome Pine‘s second week in New York, the jury was back on that question. The Trail of the Lonesome Pine belongs in the history books for having gone far to prove the viability of color in commercial moviemaking.

And Lonesome Pine outdoes Becky artistically, too. The plain truth is, the subtleties and nuances of Thackeray’s Vanity Fair resist compression to the length of a single feature (in Becky Sharp‘s case, only 83 minutes), while a broad-stroke melodramatist like John Fox is tailor-made for it. Hathaway’s movie may not have the reach of Mamoulian’s, but it has a surer grasp. And audiences still respond to it emotionally, just as they did in 1936 (and ’49, and ’56). For that reason, though it’s 16 minutes longer than Becky Sharp, it feels half an hour shorter.

The raw emotionality of the story, set against the mountain feud between the Tolliver and Falin clans, makes the movie powerful. Even if it looked like outmoded hokum to the sophisticated critics of the day, audiences ate it up, and they still do. The emotion is close to the surface, whether full-bore in Sylvia Sidney’s screaming for blood or in the quiet moment here (Hathaway’s favorite shot in the entire picture). I won’t explain what’s happening, you’ll have to discover that for yourself. But if it doesn’t bring tears to your eyes, as they say, check your pulse. John Ford and Jean Renoir at their best could never have bettered the poetry of this heartbreaking shot.