The Last Cinevent, the First Picture Show — Day 2

Cinevent Day 2 began with Chapters 4 – 6 of King of the Texas Rangers. Bob Bloom’s program notes tell us that this serial was filmed on location in the San Bernardino National Forest from June 17 to July 18, 1941 at a total cost of $139,701 (the production ran $1,165 over budget). Just for fun, let’s assume the standard six-day work week of the time, and let’s assume the company took no time off for the Fourth of July (though in fact they probably did). That means a shooting schedule of 28 days for a production running a total of 3 hours 35 minutes — in other words, on an average day directors Witney and English got about seven-and-a-half minutes of usable film in the can while spending $4,989.32. In Day 1’s notes I described Republic Pictures as an “economical” studio; giving credit where it’s due, it was also a pretty well-oiled operation, especially considering that it had been in existence for only six years.

The first feature of the day was the British film of Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado (1939), in a beautiful IB Tech print showcasing that inimitable British Technicolor, so much more delicate than the American variety. And here I insert the notes I wrote for the Cinevent program book:

The first feature of the day was the British film of Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado (1939), in a beautiful IB Tech print showcasing that inimitable British Technicolor, so much more delicate than the American variety. And here I insert the notes I wrote for the Cinevent program book:

It wasn’t only Hollywood movies that had a good year in 1939. That was also a banner year for Gilbert and Sullivan’s most popular comic opera. First — in September 1938, actually — came The Swing Mikado, produced by the Chicago branch of the WPA’s Federal Theatre Project with an all-African-American cast, and with Sir Arthur Sullivan’s music given a jazzy jitterbug beat. After a five-month run in Chicago, it was transplanted to Broadway for another three months. Not to be outdone, Broadway showman Michael Todd mounted his own all-Black (and even jazzier) production, The Hot Mikado, featuring Bill “Bojangles” Robinson in the title role. After a Broadway run of 85 performances, the show was transplanted to the New York World’s Fair of 1939-40, where it was a popular attraction during both seasons of the fair.

Coming close on the heels of both of these, even overlapping by a few days, was producer Geoffrey Toye and director Victor Schertzinger’s screen adaptation of The Mikado, a more traditional production, filmed in England but with American talent on both sides of the camera. The movie was the brainchild of first-time producer Toye. From 1919 to 1924, Toye had been musical director for the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company, custodians of the Gilbert and Sullivan canon while the works were still under copyright. In that capacity he had earned the trust and respect of Rupert D’Oyly Carte, son of the company’s illustrious founder, even after the two had gone their separate professional ways.

And so it was, in the late 1930s, that Toye was able to obtain the film rights to all of Gilbert and Sullivan’s works. His plan was to produce a series of film adaptations over the coming years, with his first production to be The Yeomen of the Guard.

Toye’s first move was to travel to Hollywood, as he said, “in search of technical experts.” It didn’t take him long to decide that The Mikado would be a more bankable title this first time out of the gate. At the same time, he decided his movie would have to be in Technicolor — a bold and prescient decision, since at that point only three British films had been made in Technicolor. Mikado would be the fourth.

It wasn’t only “technical experts” Toye was looking for over here. Once he decided on Mikado instead of Yeomen, the first item on his wish list was to get Deanna Durbin to play Yum-Yum. Alas for Toye and movie history, Universal wouldn’t allow it — yet another example, as if one were needed, of the short-sighted stupidity with which the studio mismanaged the career of its biggest star. Ironically, Universal eventually wound up being The Mikado‘s U.S. distributor. I wonder: did the bright boys in the front office ever regret not letting Durbin appear in it?

So Toye was denied his first-choice star, but he didn’t go home empty-handed. By the time he sailed for England, he had secured the services of Victor Schertzinger to direct. It was another canny choice; Schertzinger was a trained musician and composer as well as director, and had been Oscar-nominated for directing Metropolitan Opera star Grace Moore in One Night of Love (1934). Also, to play Nanki-Poo, the incognito son of the emperor of Japan, Toye signed another American, radio and recording star Kenny Baker. It was a move to shore up the movie’s chances at the American box office, and despite some grumbling from G&S purists (British wags called him “Yankee-Poo”), Baker acquitted himself quite nicely.

For other roles, Toye turned to the D’Oyly Carte Company. Sydney Granville, a D’Oyly Carte star off and on since 1907, made his only film appearance as the officious Pooh-Bah, while Martyn Green, in his prime at 39 and midway through his 29-year tenure at D’Oyly Carte, played Ko-Ko, the Lord High Executioner. Toye also enlisted the D’Oyly Carte chorus, filling out the larger ensemble for the film with alumni of the company. Non-company players Jean Colin (as Yum-Yum), Constance Willis (Katisha) and John Barclay (the Mikado) rounded out the cast.

During production, Schertzinger reportedly received as many as 3,000 letters a week threatening “dire consequences” if he tampered unduly with the show’s sacred text. The letter-writers need not have worried; while the show was somewhat rearranged and several songs were cut to get the running time down to 90 minutes, the result was quite faithful to Gilbert and Sullivan’s satiric spirit. (And by the way, it was understood then, as it had been in 1885, that the butt of The Mikado‘s satire was Great Britain, not Japan.) In the New York Times, Frank S. Nugent called the movie “one of the most luscious productions of the operetta in history” (though he wondered if this purely theatrical piece was a good candidate for filming in the first place). Variety’s “Jolo” called it a “thoroughly ingratiating satire, carefully concocted.” The critics also praised the picture’s pastel Technicolor photography, which was justly nominated for an Academy Award (though of course this was 1939, and nothing was going to take that Oscar away from Gone With the Wind).

During production, Schertzinger reportedly received as many as 3,000 letters a week threatening “dire consequences” if he tampered unduly with the show’s sacred text. The letter-writers need not have worried; while the show was somewhat rearranged and several songs were cut to get the running time down to 90 minutes, the result was quite faithful to Gilbert and Sullivan’s satiric spirit. (And by the way, it was understood then, as it had been in 1885, that the butt of The Mikado‘s satire was Great Britain, not Japan.) In the New York Times, Frank S. Nugent called the movie “one of the most luscious productions of the operetta in history” (though he wondered if this purely theatrical piece was a good candidate for filming in the first place). Variety’s “Jolo” called it a “thoroughly ingratiating satire, carefully concocted.” The critics also praised the picture’s pastel Technicolor photography, which was justly nominated for an Academy Award (though of course this was 1939, and nothing was going to take that Oscar away from Gone With the Wind).

Geoffrey Toye’s plan to produce a series of Gilbert and Sullivan films, with the approval and participation of the D’Oyly Carte Company, was off to a good start, but there would be no further installments. The project was doomed first by the outbreak of World War II, then by Toye’s untimely death at 53 in 1942. It’s a pity we were denied a record of Sydney Granville and Martyn Green’s performances in, say, Yeomen of the Guard, H.M.S. Pinafore and The Pirates of Penzance – but let us count our blessings. After all, the Hot and Swing Mikados have survived only on scratchy phonograph records and in grainy silent home movies, while Victor Schertzinger and Geoffrey Toye’s rendition has come down to us exactly as audiences saw it in 1939.

After The Mikado came some comedy shorts from Hal Roach’s Lot of Fun bookending the lunch break. Before lunch it was We Faw Down (1928), a late silent with Laurel and Hardy — albeit one with a sound-on-disk Vitaphone musical score and sound effects. The long-lost disks were recently rediscovered, and Cinevent saw a print with the Vitaphone accompaniment restored on a conventional soundtrack.

After The Mikado came some comedy shorts from Hal Roach’s Lot of Fun bookending the lunch break. Before lunch it was We Faw Down (1928), a late silent with Laurel and Hardy — albeit one with a sound-on-disk Vitaphone musical score and sound effects. The long-lost disks were recently rediscovered, and Cinevent saw a print with the Vitaphone accompaniment restored on a conventional soundtrack.

The short had quite a pedigree. It not only starred The Boys, but was directed by Leo McCarey (The Awful Truth, Going My Way, An Affair to Remember) and photographed by future director George Stevens (Gunga Din, Shane, Giant).

And there was a special bonus for movie trivia buffs: Pictured here in the role of Mrs. Stanley Laurel was none other than the one and only Bess Flowers, surely the most prolific actor, male or female, in movie history. She sometimes had lines, but usually didn’t; was sometimes credited on screen, but usually wasn’t. Still, between 1923 and 1969 she ran up an unapproachable record of 966 movie and TV appearances. Bess had an extensive wardrobe and could dress for any occasion this side of a Stone Age cave-warming, so plugging her into a crowd scene was one less hassle for a casting director and costumer. Check out her filmography; you’ll see a lot of “Party Guest”, “Nightclub Patron”, “Ship’s Passenger”, “Audience Member”, “Secretary”, “Nurse”, “Maid”, and so on. Lines or no lines, seldom more than a few day’s work, but my lord, the lady kept busy: 28 movies in 1939, 35 in 1940, 48 in 1941. She was well-known and well-liked in the industry, obviously — you don’t amass nearly a thousand credits if you make people say, “Uh-oh, here comes trouble!” Bess Flowers retired after an episode of The Red Skelton Hour in 1969 and died in 1984 at the Motion Picture Country Home, age 85.

In We Faw Down, Stan and Ollie tell their domineering wives (Stan and Ollie’s wives were always domineering) that they’re going to a vaudeville show with their boss, but they’re really going to a big poker game. Then on the way to the game they get sidetracked into a pied-à-terre with two good-time gals. Meanwhile, unbeknownst to them, the wives learn that the vaudeville theater has burned down. Complications ensue. It all culminates in one of Laurel and Hardy’s all-time-greatest closing gags, involving the wives, a shotgun, and two adjacent apartment buildings. If you’ve seen We Faw Down, you don’t need more hint than that; if you haven’t, I won’t spoil the gag.

After lunch the Hal Roach parade continued with three Charley Chase silent shorts: The Fraidy Cat (1924), A Ten-Minute Egg (also ’24), and A Treat for the Boys [a.k.a. The Sting of Stings] (’27). Charley was definitely in his prime in those days, still finalizing his persona in the first two and really hitting his stride in the third. Personally, I’ve always rather preferred his sound shorts of the 1930s, mainly for his tendency to break into song (he was a very appealing musical performer). There’s no denying, though, that in the silent ’20s Charley Chase was younger, more energetic, and further away from that early grave he would drink himself into at 46 in 1940.

Film musical historian and aficionado Richard Barrios hosted a “Vol. 2” session of Songs in the Dark and Dangerous Rhythms (continuing what he started at Cinevent 51 all those months ago), an assortment of musical numbers old and new(er). The title, of course, alludes to Richard’s books A Song in the Dark: The Birth of the Musical Film and Dangerous Rhythm: Why Movie Musicals Matter (both of which belong in every movie buff’s library).

Film musical historian and aficionado Richard Barrios hosted a “Vol. 2” session of Songs in the Dark and Dangerous Rhythms (continuing what he started at Cinevent 51 all those months ago), an assortment of musical numbers old and new(er). The title, of course, alludes to Richard’s books A Song in the Dark: The Birth of the Musical Film and Dangerous Rhythm: Why Movie Musicals Matter (both of which belong in every movie buff’s library).

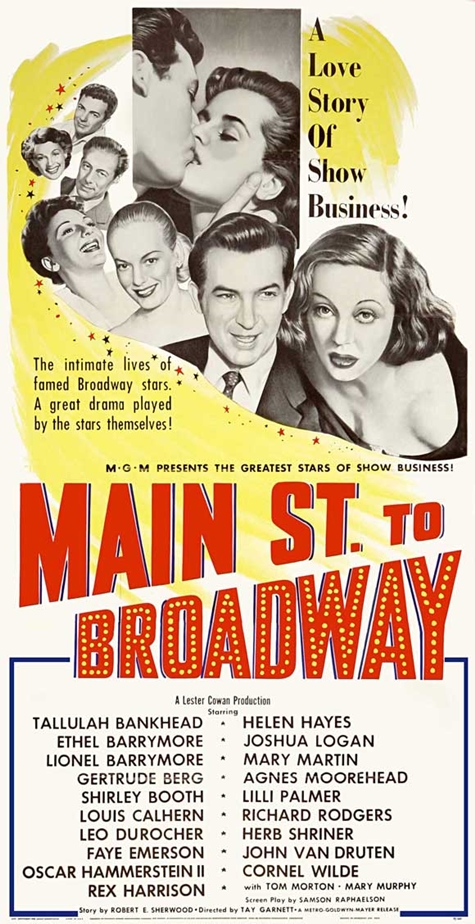

Next, Richard introduced Main Street to Broadway (1953), a broken-heart-for-every-light-on-Broadway drama distinguished by a roster of guest stars being trotted out for drive-by appearances. The stars were cajoled into appearing through a tie-in between independent producer Lester Cowan and the Council for the Living Theatre, a public relations group formed in 1947 by Pulitzer Prize playwright Robert E. Sherwood (who supplied Main Street to Broadway‘s story, such as it was) on the occasion of the bicentennial of the American (read “New York”) theater. In return for providing the big names, the Council stood to get a 25 percent share of the movie’s profits. Unfortunately, there weren’t any.

The picture’s central (stock) characters were played by two names in the fine print at the bottom of this list: Tom Morton as Angry Young Playwright With Chip on Shoulder and Mary Murphy as Small Town Girl Straight Out of High School Drama Club Taking Fling at Acting Career. Then as now, Main Street‘s chief interest was the parade of stars, most gamely playing themselves for a minute or two of screen time. (Exceptions: Tallulah Bankhead, in a major support, played a good-sport parody of herself; Agnes Moorehead camped it up as Morton’s drama-queen agent; and Gertrude Berg played her radio/TV sitcom character Molly Goldberg as if she existed in the real world.) Others not listed on this poster included director Joshua Logan, Henry Fonda, Vivian Blaine, caricaturist Al Hirschfeld, Stuart Erwin, Jeffrey Lynn, society hostess Elsa Maxwell, and Broadway critics Brooks Atkinson, Ward Moorehouse and John Mason Brown.

Actually, there was one other point of interest beside this gaggle of celebs from the Golden Age of Broadway. As the movie’s nominal leads, Tom Morton and Mary Murphy played stereotypical opposites-who-attract: He disdains her bourgeois primness, she resents his snotty condescension, but (as the top picture on the poster suggests) they absolutely cannot keep their hands off each other. When Main Street to Broadway was released in October 1953, Morton, 27, was just beginning his six-year, seven-credit career, while Murphy, 22, was two months away from her best-remembered role as the police chief’s daughter playing with Marlon Brando’s fire in The Wild One. For most of Main Street, Morton and Murphy were blandly likeable, but when they went into the clinches (which was often), they hungrily devoured each other, fairly steaming up the camera lens and exuding a sexual chemistry far beyond anything Murphy would show with Brando. I couldn’t help wondering what was going on between these two when the cameras weren’t rolling. When I shared this thought with another audience member, she said, “From what I understand, there was quite a lot going on!” (Mind you, I don’t know who this person was, or what she knew or how she knew it. I pass her observation on as the rankest gossip, and meaning no offense to Ms. Murphy’s memory — she died in 2011 — or to Mr. Morton, who is evidently still with us at 95.)

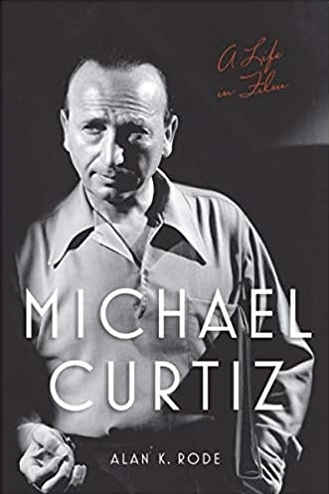

When the lights came up after Main Street to Broadway, it was time for dinner. When we came back, it was to a presentation by biographer Alan K. Rode, author of Michael Curtiz: A Life in Film. In his excellent, well-researched book, Rode makes a persuasive case for Curtiz as one of the most prolific and versatile artists — yes, artists — ever to work in Hollywood. I rather suspect that he may have been preaching to the choir at Cinevent — at least I certainly hope that Cinevent-goers appreciate Curtiz’s body of work more than the average citizen. For that matter, I hope we appreciate him more than some film critics and theorists, who tend to look down on prolific filmmakers (Curtiz directed 178 movies) as somehow unserious. If nothing else, Alan Rode’s lecture was a timely reminder of what we already know — or should. (By the way, Rode’s biography tells us that Curtiz, who was born Manó Kaminer, pronounced his professional name “Cur-tezz“, not “Cur-teez“. And while we’re on the subject, Alan Rode’s own surname is pronounced “Roadie”.)

When the lights came up after Main Street to Broadway, it was time for dinner. When we came back, it was to a presentation by biographer Alan K. Rode, author of Michael Curtiz: A Life in Film. In his excellent, well-researched book, Rode makes a persuasive case for Curtiz as one of the most prolific and versatile artists — yes, artists — ever to work in Hollywood. I rather suspect that he may have been preaching to the choir at Cinevent — at least I certainly hope that Cinevent-goers appreciate Curtiz’s body of work more than the average citizen. For that matter, I hope we appreciate him more than some film critics and theorists, who tend to look down on prolific filmmakers (Curtiz directed 178 movies) as somehow unserious. If nothing else, Alan Rode’s lecture was a timely reminder of what we already know — or should. (By the way, Rode’s biography tells us that Curtiz, who was born Manó Kaminer, pronounced his professional name “Cur-tezz“, not “Cur-teez“. And while we’re on the subject, Alan Rode’s own surname is pronounced “Roadie”.)

Then Mr. Rode introduced Private Detective 62 (1933), one of Curtiz’s lesser-known Warner Bros. Pre-Code pictures. William Powell played a U.S. diplomat stationed in Paris who, for reasons we needn’t go into, is forced to resign in disgrace. Back in the States and scrambling for work, he falls in with an unscrupulous detective agency running the old badger game, entrapping “marks” in compromising situations, then blackmailing them to keep things quiet. Powell’s life gets complicated when he finds himself falling for his latest victim (Margaret Lindsay). Paced by Curtiz at a breakneck 66 minutes, it was far-fetched but diverting. Powell and Lindsay were supported by Ruth Donnelly, Arthur Hohl, James Bell — and, as a gangland casino operator, the ill-fated Gordon Westcott. Westcott would go on to earn his own footnote in history in 1935 when, riding for MGM in a polo game against a team led by Walt Disney, his horse fell on him and crushed his skull. He lingered unconscious for three days in hospital, finally dying a week short of his thirty-second birthday. His death dampened Hollywood’s enthusiasm for polo; Lillian Disney put her foot down, and her husband had to find other diversions to occupy his spare time. Like model-railroading. And daydreaming about building an amusement park. All because of Gordon Westcott’s bad luck on the polo field.

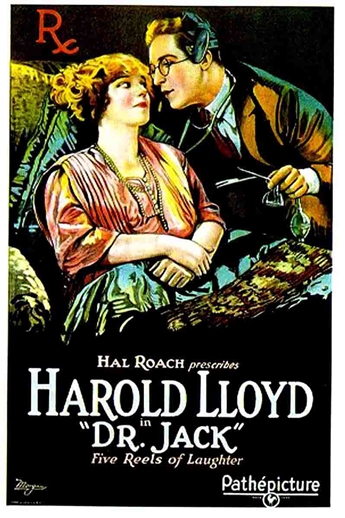

Dr. Jack (1922) was Harold Lloyd’s second venture into feature-length comedy, and he was still getting the hang of it. Lloyd played a small-town doctor who takes on the case of a patient billed as “The Sick Little Well Girl” (Mildred Davis) when he suspects her family is being milked by a “specialist” who not only has no intention of “curing” her, but knows full well she’s not really sick in the first place. The picture feels like two or three of Lloyd’s shorts strung together, but it’s fun for all that, with some rewarding scenes (like a nifty poker game) that contribute more to the comedy than to the picture’s putative plot. The proceedings are added to by cameos from Mickey Daniels and Jackie Condon, two of the first round of producer Hal Roach’s Our Gang kids, plus an appealing canine who (Samantha Glasser speculates in her program notes) looks enough like Pete the Pup of the 1930s Our Gang to have been an ancestor.

Dr. Jack (1922) was Harold Lloyd’s second venture into feature-length comedy, and he was still getting the hang of it. Lloyd played a small-town doctor who takes on the case of a patient billed as “The Sick Little Well Girl” (Mildred Davis) when he suspects her family is being milked by a “specialist” who not only has no intention of “curing” her, but knows full well she’s not really sick in the first place. The picture feels like two or three of Lloyd’s shorts strung together, but it’s fun for all that, with some rewarding scenes (like a nifty poker game) that contribute more to the comedy than to the picture’s putative plot. The proceedings are added to by cameos from Mickey Daniels and Jackie Condon, two of the first round of producer Hal Roach’s Our Gang kids, plus an appealing canine who (Samantha Glasser speculates in her program notes) looks enough like Pete the Pup of the 1930s Our Gang to have been an ancestor.

As things turned out, Dr. Jack had two happy endings, one of them in real life. Just two months after the picture’s release, on February 3, 1923, Harold Lloyd and Mildred Davis were married, and they stayed that way until death did them part in 1969. Generations of Lloyds rose up and called them blessed.

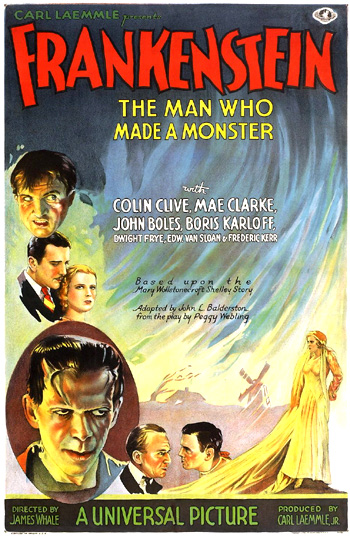

In keeping with Cinevent 52’s Halloween Weekend setting, Day 2 closed out with Frankenstein (1931). Do I really need to say much about this one? After ninety years, it’s still one of the most famous movies ever made. However, at the risk of being burned for heresy, I will venture to suggest that the picture shows its age rather badly, and has ever since I first saw it sixty years ago — admittedly, on TV, and in the expurgated form of its Post-Code reissues that held sway until the 1980s. Cinevent, of course, screened the uncut Pre-Code version.

In keeping with Cinevent 52’s Halloween Weekend setting, Day 2 closed out with Frankenstein (1931). Do I really need to say much about this one? After ninety years, it’s still one of the most famous movies ever made. However, at the risk of being burned for heresy, I will venture to suggest that the picture shows its age rather badly, and has ever since I first saw it sixty years ago — admittedly, on TV, and in the expurgated form of its Post-Code reissues that held sway until the 1980s. Cinevent, of course, screened the uncut Pre-Code version.

What unarguably survives intact from 1931 is Boris Karloff’s performance, simultaneously menacing, repellent, heart-wrenching and pathetic, absolutely iconic in the purest sense of the word. His first appearance, with Arthur Edeson’s camera leaping ever closer to his undead face in wavering hand-held quick cuts, still has the power to take our breath away, and could raise gooseflesh on a marble statue.

But much of the movie, to me anyhow, feels slapdash and incomplete. I think its reputation owes much to its sequel The Bride of Frankenstein (1935), which was an exponential improvement — possibly the greatest ratio of improvement for a sequel to its original in movie history. If nothing else, Franz Waxman’s ominous musical score makes a huge difference; the lack of music in the original fairly screams its absence. There are other improvements: John Fulton’s photographic effects complement and enlarge the mechanical effects of Ken Strickfaden. The prissy epicureanism of Ernest Thesiger’s Dr. Pretorius provides a foil for Colin Clive’s neurotic energy that he didn’t find in John Boles, Mae Clark, or that blustering old fart (Frederick Kerr) who played his father. There is simply no end to the ways The Bride is better than Frankenstein. Still, there’s no denying the obvious: Without the original, we wouldn’t have had the sequel. We can be thankful for that. And for Boris Karloff.