Remembering the Night

This post is adapted and expanded from an article I wrote for the November 22, 2007 issue of the Sacramento News & Review.

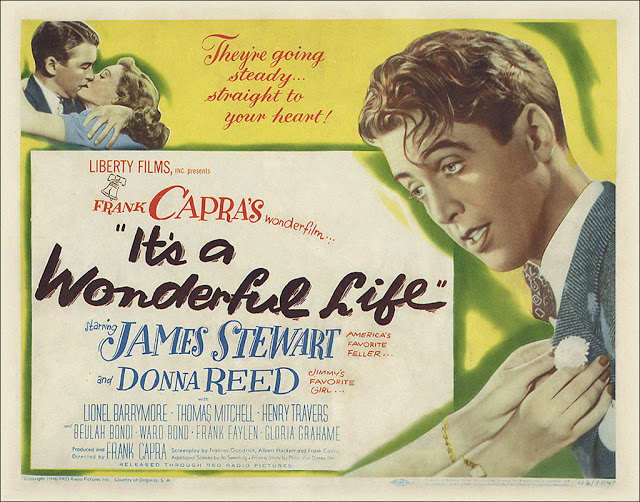

I always dread this time of year, when the holiday movies are trotted out. You can’t turn around without hearing some jackass bitch about how much he hates It’s a Wonderful Life. He can’t get enough of “I am your father, Luke” or “I’m King o’ the World!”, but Zuzu’s petals once a year is just more than he can bear.

It makes me nostalgic for the days when I had It’s a Wonderful Life all to myself (and yes, there was such a time). Well, almost to myself, anyhow. Certainly everybody else who knew and loved Frank Capra’s picture had my own last name. Back about 1974 or so, in college, I had two friends who made a nightly ritual of staying up to watch car dealer Jay Brown’s all-night movies on Channel 36 out of San Jose. One day — and it was nowhere near Christmas — they rushed up to me bubbling with enthusiasm for this great Jimmy Stewart movie they’d seen the night before. They figured if anyone would know about it, I would, and they were right. That was — for me, anyhow — the beginning of the revival of It’s a Wonderful Life. And the beginning of the end for my family and me having the memory of It’s a Wonderful Life all to ourselves. Don’t get me wrong: I’m glad the picture finally came into its own, and I thank a merciful Providence that Capra, Stewart and Donna Reed all lived to see it. But then again, when people like that hypothetical (but all too credible) killjoy I mentioned above feel free to rag on it, sometimes I’m not so sure.

So I almost hesitate to mention Remember the Night. Maybe I wouldn’t, but the cat seems to be getting out of the bag. When I wrote about Remember the Night in 2007, it was available only on out-of-print used VHS or bootleg copies of an AMC broadcast from the 1990s. Things are different now; the movie’s available in an above-board (and beautiful) DVD from the TCM Web site, and I figure it’s only a matter of time before someone runs up to me bubbling with enthusiasm about this great Fred MacMurray-Barbara Stanwyck movie they saw the other night. I want to be able to say I’m way ahead of them.

Most of the reason for Remember the Night‘s resurgency — I mean in artistic terms, independent of the arcane ins and outs of who owns a film and who decides there’s a market for it — is its writer, Preston Sturges. This was the last script he ever wrote for somebody else to direct, the somebody in this case being Mitchell Leisen, then the alpha dog among Paramount directors (a position he would soon cede to — or at least share with — Sturges himself). Leisen’s star has slipped a bit since his heyday in the ’30s and ’40s, alleviated somewhat by an excellent biography, Mitchell Leisen: Hollywood Director by David Chierichetti, originally published in 1973 (the year after Leisen died), then revised and expanded in 1995. I’ll have more to say about some of Leisen’s pictures later.

Right now I’m talking about Remember the Night. The version of Sturges’ script published in Three More Screenplays by Preston Sturges is a facsimile of Sturges’ actual typescript, dated June 15, 1939 and bearing the title The Amazing Marriage. Written in by hand on the title page is “Remember the Night[,] Or”. Obviously, neither Sturges nor producer-director Leisen ever came up with a really good title. The Amazing Marriage at least has some slight connection to a line from the script, albeit one Leisen cut during shooting. The picture’s final title, though, is so generic as to be meaningless.

If the title is generic, however, it’s the only thing about Remember the Night that is. Stanwyck plays Lee Leander, a hardboiled, tough cookie who gets busted in New York for lifting a diamond bracelet from a Fifth Avenue jewelry store. MacMurray is assistant D.A. Jack Sargent, about to leave town to drive to his mother’s farm in Indiana for Christmas when his boss yanks him in to prosecute Lee. Disgruntled and eager to get on the road, he takes advantage of a legal technicality and gets the case continued until after New Year’s. Then he begins feeling guilty about leaving Lee in jail over the holidays and arranges to get her bailed out. To his surprise and discomfort, the bail bondsman remands Lee to his custody, and the surprise is compounded when, despite the fact that he was prosecuting her only that afternoon, the two find themselves taking a liking to one another. They even learn that they grew