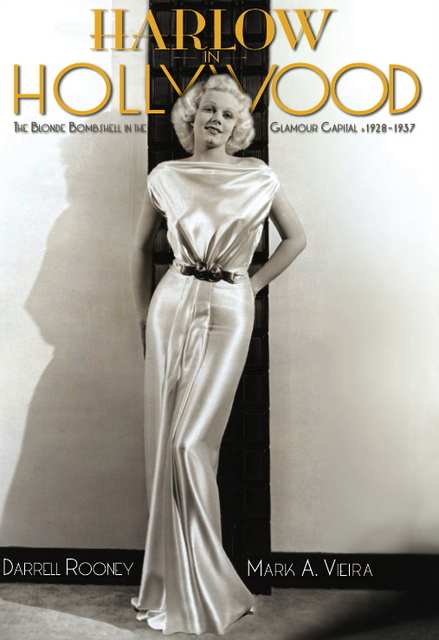

I ended my last post with the shadow of Jean Harlow’s name on the directory outside the star dressing rooms at the MGM studios. It was a ghostly image; the haunting is considerably more tangible in another new book, Harlow in Hollywood: The Blonde Bombshell in the Glamour Capital, 1928-1937 by Darrell Rooney and Mark A. Vieira, published to coincide with the 100th anniversary of Harlow’s birth (March 3, 1911). This sleekly sumptuous coffee-table volume does a great job of evoking both “H”s in the title. I can’t help comparing it to the late Ronald Haver’s David O. Selznick’s Hollywood, even at the risk of overpraising Harlow in Hollywood — at least in my own mind, since I consider Haver’s book just about the best single title ever published on Golden Age Hollywood. There never was such a visual and factual feast as that Selznick book, but Harlow in Hollywood is in the same league.

What really set the new book apart are its visuals — the cascade of pictures (there must be 400 or more) from the authors’ own collections and what they’ve garnered from other sources (duly thanked in the acknowledgments), all dazzlingly arranged by designer Hilary Lentini. The evocative beauty of Lentini’s design extends even to the whimsical endpapers, adapted from a 1937 Starland Map and dotted with “pins” marking locations that were significant in Harlow’s life and career. These endpapers go far to conjure up a cozy, sun-soaked little cluster of everybody-knows-everybody communities — Hollywood, Westwood, Beverly Hills, Laurel Canyon — that’s a far cry from the cramped, smoggy, seedy melange of urban sprawl, faded glory and retro kitsch that greets visitors to the L.A. Basin today. (Of course, the map probably had more than a touch of gaga fantasy even then.)

If Harlow in Hollywood doesn’t quite match the visual splash of David O. Selznick’s Hollywood, it’s probably because it doesn’t have the Haver book’s riot of eye-popping color. Which is only fitting: Selznick was an early champion of Technicolor and used it when others told him he was a fool to waste the money; but Selznick figured color would pay off in the long run by adding shelf life to his pictures (and he was right).

Not that there isn’t color in Harlow in Hollywood — like these striking Carbro color images taken by George Hurrell in late 1935 or early ’36. These pictures are from her “brownette” period late in her career (nobody knew how late), when MGM sought to placate the Breen Office by softening the erotic edge of her platinum blonde image. It’s not as if they had much choice. Harlow’s hair really had that white-blonde sheen in childhood and adolescence (and she was only 17 when she started in pictures), but every blonde’s hair color deepens and thickens with maturity, and Harlow was no exception. Stringent efforts to retain that platinum blonde look — peroxide, ammonia, Lux flakes — had ravaged her scalp and hair to the point where she was in real danger of going bald. I suspect part of the reason for the Hurrell portraits was to prepare Harlow’s fans for her new look.

But color portraits or no, Harlow was made for black and white. She was made by black and white, too, as this portrait on the set of Bombshell shows — she’s so much more alluring and accessible here, isn’t she? Harlow in Hollywood has picture after picture like this; the authors’ point is that Harlow was endlessly fascinating, and they prove it.

There are pictures like this one too, more candid shots, away from the controlled atmosphere of the studio with its careful grooming and flattering lighting, its makeup artists and glamour photographers. Here she is in 1936 at the Cocoanut Grove with William Powell…

…and again in court in 1935, seeking a divorce from

her third husband, cinematographer Hal Rosson. Harlow

is still Harlow, still glamourous and photogenic — but

her eyes look sunken and baggy, at least to me. Is it just

the sad wisdom of hindsight, or does Harlow really look

like a woman in failing health? Did anybody notice it at

the time? Or did they just put it down to her late hours

and heavy drinking? There was plenty of both. (Sitting

with her in this picture is her mother, the real Jean Harlow

— that is, the one born with the name that 17-year-old

Harlean Carpenter adopted when she registered with

Central Casting. Was that Harlean’s awkward tribute

to the mother who had wanted to be a movie star

more than she ever did? Whatever it was, Harlean

was stuck with her mother’s maiden name

from then on.)

What would have happened to Harlow if she had lived? Might she have, as some suggest, transferred her comic talent to TV as she slipped into middle age, the way Lucille Ball (five months younger than Harlow) did? Maybe; youth enhanced Harlow’s comic charm but didn’t define it. But the fact is, it wasn’t to be, not because she died young, but because she was probably dying — or at least doomed — before she ever set foot in California. An attack of scarlet fever at 15, probably followed by an undiagnosed kidney infection, had started her on a protracted and undetected course of kidney failure that finished her off 11 years later. There were no transplants or dialysis machines in those days; when your kidneys gave out that was it, you were a goner. The pressure of work and pleasing her mother, three failed marriages (one terminated by her husband’s grisly suicide), two abortions, an appendectomy, oral surgery and alcoholism may have sapped her constitution and will to live and brought the end that much sooner, but odds are Jean Harlow was never going to make it to the Age of Television no matter what.

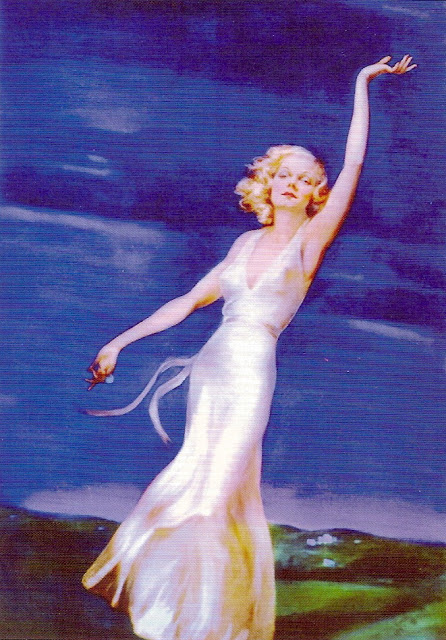

Harlow in Hollywood covers all that — you can scarcely ignore it — but it’s no scandal-wallow. If the book wallows in anything, it’s in the glamour of Harlow’s Hollywood — the movies, the premieres, the mansions, the restaurants and night clubs. With things like that it’s not wallowing, it’s luxuriance. And this is a luxuriant book, richly printed on fine glossy paper in sparkling tones of silvery black and white. But I’ll close with another color image, this one a 2009 recreation of Farewell to Earth, the portrait that Harlow’s grieving mother commissioned after her death. On her right hand you can glimpse her 85-carat star sapphire ring, a 1936 Christmas present from William Powell, the love of Harlow’s life who wouldn’t marry her.

The painting embodies Mother Jean’s maudlin grief. Shunned by the industry that never liked her very much even as they adored her daughter, she made her homes a succession of shrines to her “Baby” and died in obscurity in 1958. Nobody knows what ever happened to the painting (this image was digitally colorized from a photo), or to that star sapphire ring.

But the portrait also captures something of Harlow’s beauty, grace, charm and intelligence, as does the whole book. At the list price of $50 it would be a bargain. At the $31.50 Amazon is asking, no movie buff can afford to be without it.