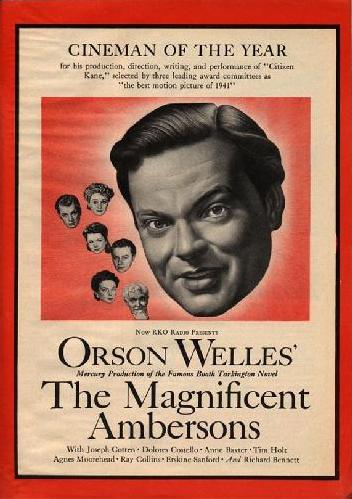

Minority Opinion: The Magnificent Ambersons, Part 3

When the U.S. declared war on Japan on December 8, 1941, the Roosevelt administration felt sure (thanks to confidential intelligence) that Nazi Germany would soon, in turn, declare war on the U.S. And sure enough Hitler did, on December 11. Even before that, however — on December 10 — the U.S. State Department approached Orson Welles. Hitler’s diplomats had been cozying up to South America for years, knowing full well that Germany would come to blows with the U.S. sooner or later, and Washington was alarmed at the number of south-of-the-border governments that had been cozying back. Shoring up relations with Latin America was a top priority. A request came from John Hay Whitney, head of the motion picture section of the State Dept.’s Office of Inter-American Affairs: Would Welles be willing to go down to South America, make a picture, and serve as a goodwill ambassador in the interests of hemispheric solidarity?

When the U.S. declared war on Japan on December 8, 1941, the Roosevelt administration felt sure (thanks to confidential intelligence) that Nazi Germany would soon, in turn, declare war on the U.S. And sure enough Hitler did, on December 11. Even before that, however — on December 10 — the U.S. State Department approached Orson Welles. Hitler’s diplomats had been cozying up to South America for years, knowing full well that Germany would come to blows with the U.S. sooner or later, and Washington was alarmed at the number of south-of-the-border governments that had been cozying back. Shoring up relations with Latin America was a top priority. A request came from John Hay Whitney, head of the motion picture section of the State Dept.’s Office of Inter-American Affairs: Would Welles be willing to go down to South America, make a picture, and serve as a goodwill ambassador in the interests of hemispheric solidarity?Would he ever. The request, forwarded through RKO and with George Schaefer’s blessing, appealed to Welles’s patriotism and political philosophy; better yet, it fit right in with one of his back-burner projects, Pan-America, since retitled It’s All True. (The new title was in fact a bit of a misnomer; the components of the project, insofar as Welles and his staff had thought them through at all, consisted of fictitious episodes, though each dealt with some sort of “truth” about life in the western hemisphere.)

Principal photography on Ambersons wrapped up on January 22, 1942; it had lasted a little over 13 weeks. Welles spent the rest of the month making pickup shots, working with Norman Foster on Journey into Fear and finishing his on-screen role in that picture, making his last broadcast of the Lady Esther radio show, and preparing to leave for South America. On February 2 he left for Rio by way of Washington D.C., where he was to be briefed by officials of the Office of Inter-American Affairs before continuing on to Brazil.

During those same two weeks, Robert Wise assembled a rough cut of Ambersons and traveled with it to Florida to intercept Welles on his way south. They spent February 5 at the Fleischer Animation Studios in Miami, recording Welles’s voice-over narration, screening the rough cut and conferring on Welles’s plans for the final cut — at least, as they stood at that point in time.

During those same two weeks, Robert Wise assembled a rough cut of Ambersons and traveled with it to Florida to intercept Welles on his way south. They spent February 5 at the Fleischer Animation Studios in Miami, recording Welles’s voice-over narration, screening the rough cut and conferring on Welles’s plans for the final cut — at least, as they stood at that point in time.It’s important to remember that what Welles and Wise worked on in Miami was just a rough cut — the barest assemblage of scenes with no music, special effects or fade/dissolve transitions. A rough cut is the movie equivalent of what in live theater is called a stumble-through, plowing through the show from beginning to end just to see what still needs work. The work that the rough cut needed is what the two men talked about that day in Miami; Wise would return to RKO and cut the picture to Welles’s specifications.

At the airport before flying out, Welles dictated a telegram to Jack Moss, the Mercury Theatre’s business manager, whom Welles had appointed a sort of surrogate producer; the telegram specified that Wise was to have the final word on editing Ambersons and that Wise’s authority was not to be questioned. In a wire from Rio three weeks later, Moss was further directed to “start running Ambersons nightly” and taking input from Norman Foster, Joseph Cotten and Dolores Costello “as many times as possible … [Y]ou know I trust you completely.”

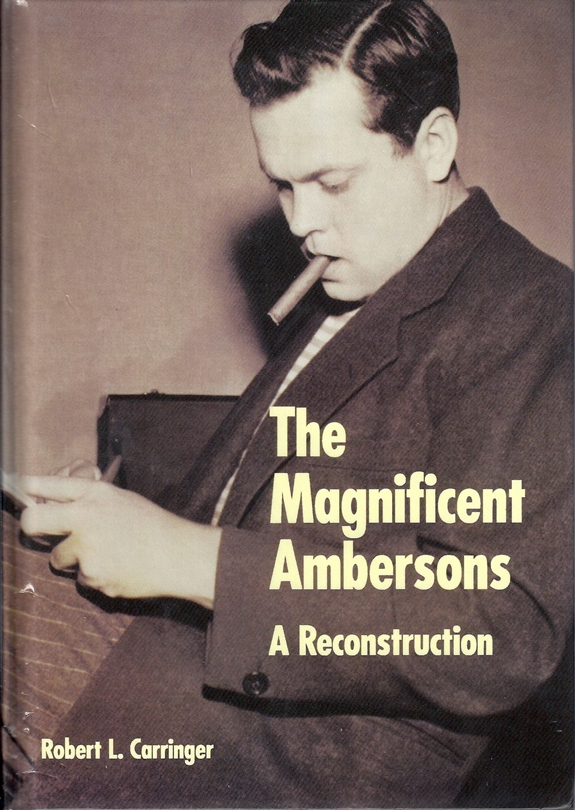

For a clear account of what happened over the four months after Welles flew to Brazil, I am indebted — we all are — to Robert L. Carringer’s The Magnificent Ambersons: A Reconstruction, published by the University of California Press in 1993. The book includes a prefatory essay, “Oedipus in Indianapolis”; an annotated copy of the cutting continuity of the first draft of the picture assembled by Robert Wise after his meeting with Welles in Miami; and a documentary history of the editing process compiled from extant studio records now housed at UCLA and Indiana University. My own conclusions regarding The Magnificent Ambersons differ somewhat from Prof. Carringer’s, but the fact that I even have conclusions is thanks to his painstaking research sifting through the surviving records of RKO and Orson Welles’s personal papers.

For a clear account of what happened over the four months after Welles flew to Brazil, I am indebted — we all are — to Robert L. Carringer’s The Magnificent Ambersons: A Reconstruction, published by the University of California Press in 1993. The book includes a prefatory essay, “Oedipus in Indianapolis”; an annotated copy of the cutting continuity of the first draft of the picture assembled by Robert Wise after his meeting with Welles in Miami; and a documentary history of the editing process compiled from extant studio records now housed at UCLA and Indiana University. My own conclusions regarding The Magnificent Ambersons differ somewhat from Prof. Carringer’s, but the fact that I even have conclusions is thanks to his painstaking research sifting through the surviving records of RKO and Orson Welles’s personal papers.“Who knows what happened?” Welles rhetorically asked Barbara Leaming in the 1980s, referring to the editing of Ambersons while he was in Rio de Janeiro. In fact, the paper trail is thorough and, while cluttered, surprisingly clear — surely one of the most complete editing records for a single picture to survive from the entire Golden Age of Hollywood. And it often flies in the face of the accepted Ambersons legend.

The spine of Prof. Carringer’s reconstruction of Ambersons is the cutting continuity compiled by RKO from the print Robert Wise shipped to Orson Welles in Rio on March 11. The running time at that point was precisely 2 hours 11 minutes 45-and-one-third seconds. (This clarifies another part of the legend, which over the years has alleged various running times, some as high as three hours, for Welles’s version of the picture.) But while this was the most complete version of Ambersons, it was never intended to be the final one; it was understood by all concerned, including Welles, that the picture was running long at 132 minutes and needed further tuning, which could include cutting or retaking scenes (or shooting new ones), and would certainly incude sneak-previewing the picture, standard practice at the time.

The picture at 132 min. contained at least some scenes that evidently never pleased anyone and were among the first things to go. For example, there were what came to be called the first and second porch scenes. The first porch scene, a long take lasting nearly six minutes, involved Isabel and Fanny chatting about their changing town while George sits lost in his own thoughts. After Isabel goes inside, Fanny worries to George that Isabel is being too hasty to leave off mourning her dead husband Wilbur. Fanny then goes inside and George, alone, fantasizes first about Lucy begging his forgiveness, then about her socializing with other young men without a thought for him. This scene might have been deemed too static; also, George’s fantasies may have played badly, may have in fact strained the resources of Tim Holt and Anne Baxter. (A significant number of the edits in the final release version of Ambersons seem to have been aimed at protecting Tim Holt’s performance.)

The second porch scene, another long take lasting a little over three minutes, came later in the picture and showed Fanny and Major Amberson discussing the Major’s financial problems and their mutual plans to invest in the ill-fated headlight company. This was in fact Richard Bennett’s longest scene in the picture, and the 71-year-old Bennett was unable to remember dialogue; Welles had been forced to feed him his lines one-by-one from off-camera, Welles’s voice to be edited out later. If that was the case here, it could well have played havoc with the timing of the scene and made it ultimately unusable. Whatever the reasons, neither porch scene (by unanimous agreement) was ever shown to an audience.

While Wise was still preparing the first cut for shipment, Welles ordered some radical changes, which came to be known as the “big cut”. The following scenes were to be taken out, beginning after George’s slamming the door in Eugene’s face and Eugene’s letter to Isabel pleading with her to stand up to George:

1. George and Isabel discussing Eugene’s letter (a different, shorter version of this scene was eventually reshot for the release version);

2. Isabel slipping a letter under George’s door telling him she will break with Eugene (this scene is not in the release version);

3. George’s walk with Lucy on the street where he tells her he and Isabel are going away, and she frustrates him by her light and trivial attitude;

4. Lucy entering a nearby shop and fainting in front of the startled clerk;

5. A poolroom scene where the clerk tells his buddies about the pretty young lady who fainted in his shop that day (not in release version);

6. The second porch scene between Fanny and Major Amberson (not in release version);

7. Uncle Jack’s visit to Eugene and Lucy, telling them of Isabel’s failing health and George’s refusal to let her come home; and

8. Isabel’s return, when she is too weak to walk a step.

In place of all this, Welles (probably by telephone) ordered Wise to insert a new scene of George finding Isabel unconscious in her bedroom, with Eugene’s letter in her hand. (This scene, not in the release version, was shot under Wise’s direction on March 10.)

Wise went ahead and shipped the first 132-minute cut off to Welles in Rio as planned. Then he made the changes Welles had called for as he prepared Ambersons for its first preview. With the changes Welles had ordered, the picture now ran approximately 110 minutes.

The Magnificent Ambersons had its first sneak preview on Tuesday, March 17, 1942 at the Fox Theatre in Pomona, Calif.

Then all hell broke loose.

Thanks, Dorian; I'll get started on that script right away! [wink] But first, of course, gotta finish this. Kim, looks like five parts'll do it.

Jim, I can well imagine an HBO miniseries, a docudrama on the frustrating making of THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS! I can see you accepting awards for your screenplay now, be they Oscars or Emmys! 🙂 Seriously, Jim, the details of your continuing saga of the film's travails have me on the edge of my seat. Great job, Jim, as always; looking forward to more MagAmbersons, as Kim put it, and seeing how it all ended up!

To Be Continued is OK for serials but criminally hard for those of us enjoying these essays. Can't wait for the rest of them. Really first-rate material here.

I hope so, Kim, but if it looks to spin out more than another 2K or so, I may have to go for Part 5. Thanks for hanging in there.

Wow! I think this series is longer than the original cut of the film! LOL! Another great edition to your MagAmbersons feature. Is Part 4 the last part?