Ups and Downs of the Rollercoaster, Part 5

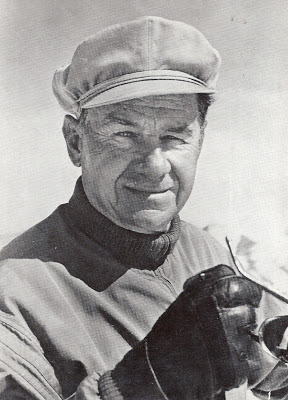

In his 1977 memoir So Long Until Tomorrow, the 85-year-old Lowell Thomas — with nearly a quarter-century of frustrated hindsight — remembered the Stanley Warner deal thus:

In his 1977 memoir So Long Until Tomorrow, the 85-year-old Lowell Thomas — with nearly a quarter-century of frustrated hindsight — remembered the Stanley Warner deal thus:“Our original group of founders had dwindled — Fred Waller, the gentle, bespectacled genius who started it all, had died before he even knew of his triumph; Mike Todd was busily hustling and working with American Optical on the process to be called Todd A-O … Arrayed against [Frank Smith], Merian Cooper and me were men of wealth who had gone into Cinerama solely for the investment possibilities, and at this critical juncture, either unwilling to go looking for the additional cash or simply ready to take their already large profits, they opted to sell out.

“The buyer was the Stanley-Warner company, and from a purely practical viewpoint, maybe the decision was not all wrong. In making it we all made a lot of money. But the bells began tolling for Cinerama then and there. Stanley-Warner was a brassiere manufacturing corporation, plus owners of a major theater chain. But they were not film producers … They didn’t really know what Cinerama was all about.”

Thomas’s memory wasn’t flawless. “Stanley Warner” wasn’t hyphenated, and “Todd-AO” was. Fred Waller lived long enough to know his triumph and collect an Oscar for it; he died in May 1954, nine months after the Stanley Warner deal was approved by the court. And Stanley Warner wasn’t “a brassiere manufacturing company”. Not yet. They didn’t purchase the International Latex Corporation (maker of, among other things, the Playtex Living Bra) until April 1954, a year after buying their six-year control of Cinerama Productions Corp. (This expansion from theater operation to ladies’ undies and baby pants was an early example of the kind of diversification that ultimately led to the entertainment conglomerates of today.)

But Thomas’s basic point was well taken. The folks at Stanley Warner, it’s true, were not film producers. And despite S.H. Fabian’s advocacy of alternate entertainment technologies — he was an early proponent of drive-in theaters, 3-D, and closed-circuit theatrical television — he really didn’t know what Cinerama was all about. Even if nobody heard it at the time, the bells were definitely tolling.

Thomas can be forgiven a certain amount of bitterness. By May 1954, Stanley Warner had managed to open only seven new Cinerama theaters and had yet to complete a follow-up feature to This Is Cinerama; yet they had managed to scrape up $15 million ($166.18 million in 2022) to buy International Latex. Moreover, in the next four years SW would lavish far more care and resources on International Latex, where profit margins were high and they were not under the thumb of the U.S. Justice Dept. Small wonder that, decades later, Thomas remembered SW being already in the brassiere business when Cinerama came along.

Stanley Warner was contractually obligated to produce a picture within the first year, and their original plan was the same as Cinerama’s before them: to involve one of the major studios in making Cinerama pictures. In early August, even before the court approved the buyout, talks were held with Columbia, Paramount and Warner Bros. All came to nothing, including a proposed picture about the Lewis and Clark expedition to star Gregory Peck and Clark Gable as the great explorers (excellent casting, that).

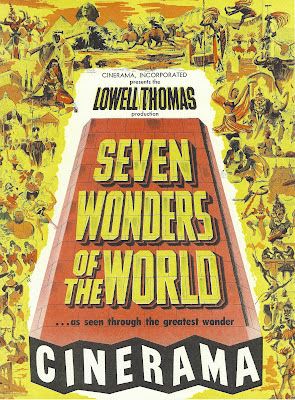

With the success of The Robe, studios began stampeding to CinemaScope in preference to the more expensive Cinerama, and any chance of a deal in that direction evaporated. SW negotiated with Merian Cooper, who was thinking of molding Paul Mantz’s 200,000 feet of aerial footage into a picture to be called Seven Wonders of the World, but talks broke down when they couldn’t agree on a completion schedule.

Cinerama Inc. made most of its money from the equipping of Cinerama theaters — the sale or lease of equipment and supplying of replacement parts — and was annoyed that Stanley Warner wasn’t opening theaters at a quicker pace. The remaining investors in Cinerama Productions were annoyed that SW wasn’t opening more theaters and producing a steadier stream of pictures to show in them. And Stanley Warner, who had to put up all the money for both the theaters and the pictures but had to share almost half of any profits (when operating costs alone could eat up as much as 90 percent of gross ticket sales), was beginning to wonder if investing in the process had been such a good idea in the first place. The cracks among the partners in Cinerama were beginning to show, and were the subject of chatter in the trade press.

Cinerama Inc. made most of its money from the equipping of Cinerama theaters — the sale or lease of equipment and supplying of replacement parts — and was annoyed that Stanley Warner wasn’t opening theaters at a quicker pace. The remaining investors in Cinerama Productions were annoyed that SW wasn’t opening more theaters and producing a steadier stream of pictures to show in them. And Stanley Warner, who had to put up all the money for both the theaters and the pictures but had to share almost half of any profits (when operating costs alone could eat up as much as 90 percent of gross ticket sales), was beginning to wonder if investing in the process had been such a good idea in the first place. The cracks among the partners in Cinerama were beginning to show, and were the subject of chatter in the trade press. There had been talk of plans to expand Cinerama into foreign countries almost from the first opening in September 1952, but nothing had ever come of that idea. In the spring of 1954, Stanley Warner sought to farm out the foreign exhibition rights — find somebody who would foot the bill for overseas expansion and pay SW for the privilege. After three months of negotiations, S.H. Fabian hammered out a deal with Nicolas Reisini, president of Robin International.

There had been talk of plans to expand Cinerama into foreign countries almost from the first opening in September 1952, but nothing had ever come of that idea. In the spring of 1954, Stanley Warner sought to farm out the foreign exhibition rights — find somebody who would foot the bill for overseas expansion and pay SW for the privilege. After three months of negotiations, S.H. Fabian hammered out a deal with Nicolas Reisini, president of Robin International.Neither Robin International nor the Greek-born Reisini had any experience in the movie business. Robin International was reportedly an import/export company, although exactly what it imported and exported wasn’t clear. Nothing shady, mind you, it’s just that Reisini seems to have had his fingers in a bewildering number of pies — none of them having anything to do with the movie industry.

But there was another factor. According to his son Andrew (interviewed for David Strohmaier’s 2002 documentary Cinerama Adventure), Nicolas Reisini as a young man had seen the Paris premiere of Abel Gance’s Napoleon in 1927 and been spellbound — especially by Gance’s three-screen “Polyvision” triptych that climaxed the picture. When Reisini saw This Is Cinerama in New York in late ’52 or early ’53, it revived that youthful excitement and seemed to be the fulfillment of Gance’s earlier vision. Son Andrew says Reisini decided on the spot that he wanted to get in on Cinerama one way or another, and when Stanley Warner went looking for someone to buy foreign rights, Reisini was ready.

Meanwhile, back home, Stanley Warner and Louis de Rochemont had fallen out over money — and SW’s reluctance to invest in perfecting the Cinerama process. De Rochemont stalked off to produce Windjammer: The Voyage of the Christian Radich in CineMiracle (a competing process just different enough to avoid infringing Cinerama’s patents). SW had enticed Lowell Thomas back to produce Seven Wonders of the World (revived after the departure of Merian Cooper). Shooting wrapped in June ’55, but as with This Is Cinerama before it, Cinerama Holiday was drawing so strongly that SW was in no hurry to release Seven Wonders (it finally opened in April 1956).

Meanwhile, back home, Stanley Warner and Louis de Rochemont had fallen out over money — and SW’s reluctance to invest in perfecting the Cinerama process. De Rochemont stalked off to produce Windjammer: The Voyage of the Christian Radich in CineMiracle (a competing process just different enough to avoid infringing Cinerama’s patents). SW had enticed Lowell Thomas back to produce Seven Wonders of the World (revived after the departure of Merian Cooper). Shooting wrapped in June ’55, but as with This Is Cinerama before it, Cinerama Holiday was drawing so strongly that SW was in no hurry to release Seven Wonders (it finally opened in April 1956).

Thanks, Dorian! I agree, it's a shame that that Lewis and Clark picture never happened; sounds to me like the perfect blend of Cinerama-genic travelogue and drama, and the spot-on casting of Peck and Gable is enough to make you wish for a portal into that alternate universe. (A pity Peck and Gable never worked together.) BTW, When Lewis and Clark did come to the screen (The Far Horizons, '55) it was as Fred MacMurray and Charlton Heston — decent enough casting, though much less stellar. (The movie itself, alas, pretty much stinks.)

I too hope you get to see Cinerama one day, though your location puts you an almost-exactly-equally-inconvenient distance from the only theaters in the world that can show it (Seattle, WA; Hollywood, CA; and Bradford, UK). Still, not entirely hopeless, and worth planning a vacation around, time and resources permitting. I encourage you to consider it.

Jim, it's a case of strange bedfellows indeed when Cinerama must join forces with the folks responsible for the Playtex Living Bra! (That said, I'm in no position to poke fun at bra manufacturers; I can say no more! :-)) Too bad the Lewis & Clark biopic with Gregory Peck and Clark Gable didn't get off the ground. Your discussion of Cinerama at its best makes me wish I could see it for myself. Great post, as always — and again, congratulations on your MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS series; you really deserve it, my friend!