Browsing the Cinevent Library, Part 2

So much for the new stuff. Moving backward in the history of publishing about 85 years, I’ve always been a sucker for movie tie-in books. Even those 1950s and ’60s Signet paperbacks with their eight-page photo inserts (“Now! A Major Motion Picture!”). But especially the really old ones from the silent era, when movie tie-ins were a frontier as unexplored as the Wild West. My 1927 novelization of London After Midnight, for example; that one turned out to be a fun read in spite of me. (I’ll be running the annual reprint of my four-part synopsis next Halloween Season, but if you’re impatient you can find it here, here, here and here.)

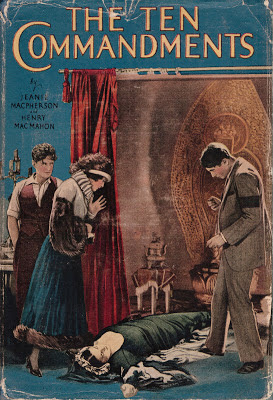

I picked up two such Grosset and Dunlap motion picture editions from one dealer at Cinevent this year, both — against long odds — with their dust jackets reasonably intact. First, this novelization of the original 1923 The Ten Commandments, “a novel by Henry MacMahon from Jeanie Macpherson’s Story Produced by Cecil B. DeMille as the Celebrated Motion Picture…” Curiously enough, the cover reproduces a scene from the modern half of the picture, rather than the first half, which recounts the more spectacular story from the Book of Exodus. (Theodore Roberts as Moses adorns the spine of the book and — along with Charles de Roche’s Pharaoh, a cast of thousands, and a couple of pyramids — the back cover.) This one has an inscription on the flyleaf: “With a Merry Merry Xmas. To Mamie Masek From Sister Rose. 1928.” Judging from the handwriting, I’d guess that the sisters weren’t exactly young even then; wherever they are now, I hope their hearts can rest secure in the knowledge that Sister Rose’s Xmas gift has found a good home.

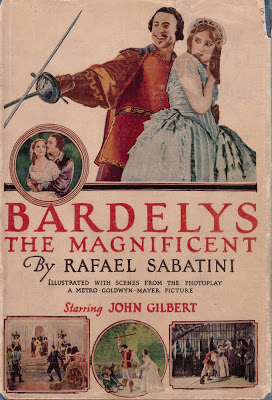

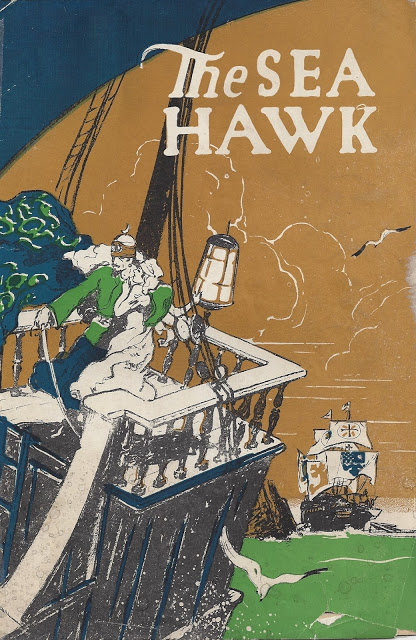

Which brings me to this. Warner Bros.’ 1940 Sea Hawk was the second picture of that title. The first was a 1924 silent from First National Pictures, directed by Frank Lloyd with Milton Sills, Enid Bennett, Lloyd Hughes and Wallace Beery. Unlike the Errol Flynn version, this one was quite faithful to the novel, telling the story of a nobleman of Elizabethan England (Sills) betrayed by his treacherous half-brother and sold into slavery in a Spanish galleon. He escapes, converts to Islam and, in time, becomes a dreaded pirate of the Barbary Coast: Sakr-el-Bahr, the Sea Hawk. When Warner Bros. absorbed First National later in the 1920s, it acquired the rights to Sabatini’s novel, and 15 years later — First National evidently having driven a harder bargain than MGM did over Bardelys the Magnificent — they made it into a vehicle for Errol Flynn, changing everything but the title and the time period. (Captain Blood, by the way, was also filmed as a silent in 1924. This was produced by Vitagraph, another company acquired in 1925 by the burgeoning Warner Bros. enterprise. Thus did the rights to this other Sabatini novel devolve onto Warners, where they sat for ten years before being dusted off and — after a false start with Robert Donat — making Errol Flynn a star. The 1924 Blood, unfortunately, survives only in a truncated digest form barely a quarter of its original length. It reposes now at the Library of Congress, waiting hopefully for more pieces to be discovered.)

But back to The Sea Hawk. What you see here is the cover to the souvenir program of the earlier, more faithful picture. I picked this up at Cinevent too — collecting souvenir programs is a favorite hobby of mine. This one is smaller than the usual program, only 6×9 inches, but it’s well designed and informative. The three-color illustration on the cover yields to two colors within, but I have to commend the designers for the number of pictures and the amount of information they managed to include — including a complete synopsis of the story (no doubt secure in the belief that nobody would read it until after they’d seen the picture).

This version of The Sea Hawk, unlike Captain Blood, survives intact, and it’s available here from the Warner Archive. It must take a back seat, of course, to the 1940 version; it doesn’t have Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s music, or director Michael Curtiz. Most of all, needless to say, it doesn’t have Errol Flynn. For all that, it’s a lavish and vigorous production, the DVD sparkles, and Milton Sills, while he’s no Errol (who was?), is a good swashbuckling hero.

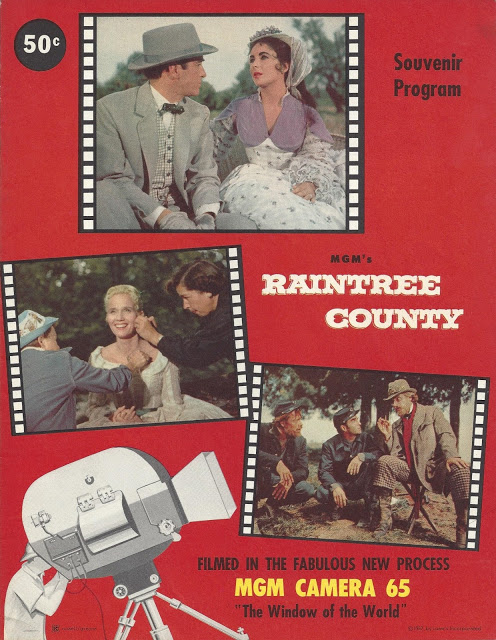

But I’ll close with this one. Not because it’s a particularly good program or from a particularly good movie — neither is the case — but because it represents one of the sorrier episodes in 1950s Hollywood, and one that has a certain significance for me because it bears on my native state of Indiana.

But I’ll close with this one. Not because it’s a particularly good program or from a particularly good movie — neither is the case — but because it represents one of the sorrier episodes in 1950s Hollywood, and one that has a certain significance for me because it bears on my native state of Indiana.Raintree County was the first and last novel of Ross Lockridge Jr. of Bloomington, Indiana (which happens to be 41 miles northeast of the town where I was born). It was published on January 5, 1948 by Houghton Mifflin and was chosen a featured selection of the Book of the Month Club. Almost exactly two months later, just as the novel was hitting the top of the New York Times bestseller list, the 33-year-old Lockridge committed suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning in the garage of his Bloomington home; it was March 6, 1948 (which happened to be five days before I was born).

Why did he do it? At the time, some speculated that after the long effort to bring his 1,066-page novel to fruition, Lockridge was exhausted and depressed at the thought of how he would ever follow it up. My uncle once expressed the opinion that Lockridge had deliberately set out to write the Great American Novel — in fact, believed that he had — and was fatally disappointed when reviews, while positive and even occasionally rapturous, failed to acknowledge it as such. I think my uncle might have hit the nail close to the head. Reading Shade of the Raintree by the novelist’s son and biographer Larry Lockridge, one thing seems clear: it was little short of a miracle that this brilliant, troubled, unstable young man lived long enough to complete his huge book.

The setting of Raintree County is a fictitious county in rural Indiana, and (like James Joyce’s Ulysses) it takes place on a single day — July 4, 1892 — following its main character, 53-year-old John Wickliff Shawnessy, and his family through the events of the day. Throughout, there are flashbacks to the past, as long ago as 1844 and as recently as earlier that same year, presented non-chronologically as they spring to the memories of Shawnessy and the other characters. It’s an ambitious, sprawling, yet carefully structured saga that seeks to summarize wholly the American experience: both everyday life and great events, as well as the aspirations, lofty or squalid, of ordinary people, and the legends and inchoate yearnings that underlie their psyches and shared culture. The book won the “Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Annual Novel Award” — actually just a publicity-savvy way of buying movie rights before publication, but it brought Lockridge $150,000. A tidy sum now, a not-so-small fortune in 1948.*

By the end of 1948, Raintree County had drifted off the bestseller lists and been aced out of the Pulitzer Prize for fiction by James Gould Cozzens’ Guard of Honor. Financial difficulties and internal power struggles at MGM put any plans to film the novel on a far-back burner.

Until 1956, when the movie that goes with this program went into production. In his biography of his father, Larry Lockridge remembered attending the world premiere in Louisville, Kentucky with his mother, brothers and sister in October 1957 (on their own dime, uninvited by MGM): “Critics agree that the movie we then watched is among the world’s worst.” This is overly harsh; the worst you can say about Raintree County — as a movie, considered by itself — is that it’s resolutely mediocre. That’s also the best you can say for it.

But that’s as a movie, considered by itself. As an adaptation of Ross Lockridge’s novel, however, there’s nothing bad enough to say about it. It’s as thorough a mangling as any novel ever got at the hands of Hollywood, and that’s saying something. Writer Millard Kaufman, a man of meager experience with little more than John Sturges’s Bad Day at Black Rock and a couple of UPA cartoons under his belt, was completely flummoxed by a book that would have challenged more talented hands than his. His solution was to jettison the flashback structure, narrow the time frame to 1859-65, and turn it into a would-be Gone With the Wind, with Elizabeth Taylor as a Scarlett O’Hara manqué. Taylor, to her credit, did her best and snagged the first of four consecutive Oscar nominations. But as John Shawnessy, Montgomery Clift (who was probably miscast in the first place) was in a near-fatal auto accident that held up production for two months while his shattered face was reconstructed, and the visible on-screen difference between his pre- and post-accident performances is a grisly thing to see.

Be that as it may, Raintree County the novel was as mutilated on purpose as Montgomery Clift had been by accident. The director was Edward Dmytryk, a workhorse as relentlessly mediocre as the Raintree County movie itself. Dmytryk later admitted — nay, boasted — that he himself had never read the book (as if we needed him to tell us that). Like The Sea Beast (Cinevent, Day 2), Raintree County is the kind of movie that gives Hollywood a bad name. My nephew, a college literature major who read the book at my suggestion, called it “definitely the greatest novel I never heard of” — and shook his head in dismay at what MGM did to it.

Imagine if David Selznick had served Margaret Mitchell as poorly as producer David Lewis, Millard Kaufman, Edward Dmytryk et al. served the dead-and-buried Ross Lockridge Jr.; would anybody ever have bothered to get Gone With the Wind right? Of course not. Nobody will ever bother with Raintree County either. And that’s just too damn bad.

——————–

*POSTSCRIPT: John McElwee at Greenbriar Picture Shows informs me that only five MGM Novel Awards were ever given, and only two were ever filmed: Raintree County and the first winner, Elizabeth Goudge’s Green Dolphin Street (awarded 1944, filmed 1947). The other winners: Before the Sun Goes Down by Elizabeth Metzger Howard in 1945; Return to Night by Mary Renault in 1946; and in 1947 a special award in addition to Raintree County‘s, to About Lyddy Thomas by Maritta M. Wolff. In May ’48 MGM discontinued the award as a belt-tightening measure. While it lasted, according to Variety, the award had constituted “the heaviest literary award in history.”

.

Silver, that business about Dmytryk not reading Raintree County is mentioned in Larry Lockridge's biography of his father; Dmytryk said it in an interview with a Canadian TV producer. I suspect he was trying to piggyback on John Ford's famous remark when asked how he made such a great film in The Grapes of Wrath: "I never read the book." In the first place, I'm not sure I believe that; I'll bet Ford was just yanking an interviewer's chain, something he loved to do. But even if he didn't read the book, he had a far better script from Nunnally Johnson than Dmytryk got from Millard Kaufman. Besides, Dmytryk on his best day was never in Ford's league; for every Crossfire or Caine Mutiny he had a Carpetbaggers, Bluebeard or Left Hand of God to pull down his average.

In his autobiography It's a Hell of a Life But Not a Bad Living, Dmytryk called Lockridge's novel — which, remember, he never read — "a long, rambling, involved story of small-town life in Indiana." He claimed Kaufman "did pretty well, mostly by ignoring a good deal of the novel and striking off in new directions."

I am quite – QUITE – jealous of your new treasures, especially Rafael Sabatini's "Bardleys the Magnificent". I didn't know Sabatini was the author of "Captain Blood", "The Sea Hawk", etc.

Sad story about the author of "Raintree County". And I can't believe Edward Dmytryk never read the book!!