Scott Eyman has been crafting definitive Hollywood biographies for over 20 years now, and each one seems to come hotter on the heels of the one before. His Lion of Hollywood: The Life and Legend of Louis B. Mayer and Empire of Dreams: The Epic Life of Cecil B. DeMille appeared only five years apart (2005 and 2010 respectively); a lesser writer — someone like, well, me for instance — might have spent 12 or 15 years on either one of them and never managed to convey the sense that yes, this must be what the man was like, as well as Scott did both times. And as if that weren’t impressive enough, in between those two he collaborated with Robert Wagner on his 2008 autobiography Pieces of My Heart.

(Full disclosure: Scott Eyman is a friend of mine. I first met him about 15 years ago and could hardly believe I was shaking the hand that wrote The Speed of Sound [1997] — the indispensible book on the talkie revolution. Scott is some years younger than I am, but I hope to be just like him when I grow up.)

Scott’s latest book is John Wayne: The Life and Legend — and yes, this must be what the man was like. This is very much a companion volume to Scott’s 1999 bio Print the Legend: The Life and Times of John Ford, and it could hardly be otherwise: the two names were linked in life and art as few others have been. Both books end with the final image from The Searchers: Wayne as Ethan Edwards, framed in the cabin door and walking away from the family reunion into a barren landscape.

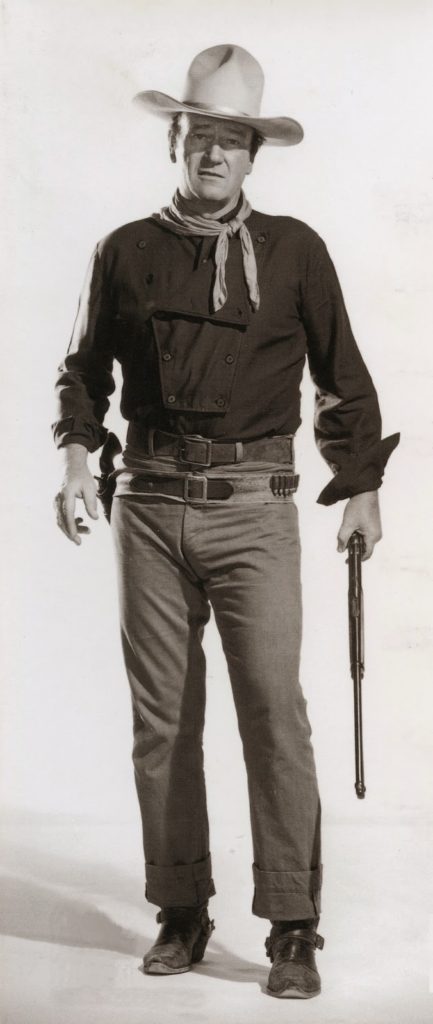

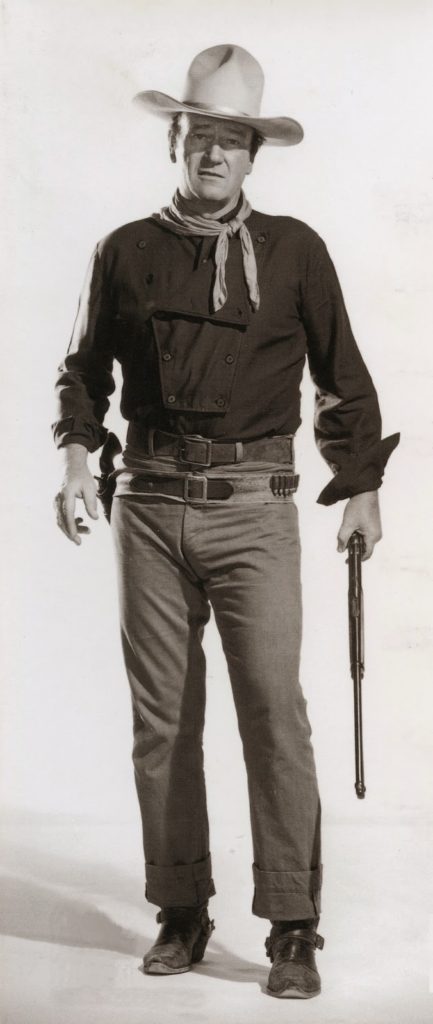

There are no bombshell revelations in John Wayne, yet the book is full of surprises — beginning with the cover, which pictures a younger, slimmer, smoother Wayne than we’re used to. (I carried the book into a Hallmark card store one day and set it on the counter while I paid for my purchase. The clerk, looking at it upside down, thought it was a picture of James Dean.)

Other surprises: The idea that Wayne stumbled into acting by accident was a myth propagated by Wayne himself. In fact, he was movie-struck from childhood, stage-struck as early as high school, and began lobbying for on-screen parts from the day he first walk onto the Fox lot as a laborer. And his feelings for his parents — the feckless father whom he adored for his kindness, the stern mother (who detested him to her dying day) whom he resented even as he paid tribute to “her strength of character, her strong sense of right and wrong, and her temper — all of which he inherited.”

Perhaps the biggest surprise for me was how separately the man viewed himself from “John Wayne”. “In Wayne’s own mind,” Scott writes, “He was Duke Morrison. John Wayne was to him what the Tramp was to Charlie Chaplin — a character that overlapped his own personality, but not to the point of subsuming it.” The Duke never legally changed his name; his death certificate identified him as “Marion Morrison (John Wayne)”.

Two quotes from the Duke, which Scott uses as epigraphs, illustrate this separation. From 1957: “The guy you see on the screen isn’t really me. I’m Duke Morrison, and I never was and never will be a film personality like John Wayne. I know him well. I’m one of his closest students. I have to be. I make a living out of him.” And again, much later: “I’ve played the kind of man I’d like to have been.” These two wistful quotes put me in mind of the famous remark by Cary Grant (who always thought of himself as Archie Leach): “Everybody wants to be Cary Grant. Even I want to be Cary Grant.”

Scott gives us a picture of Wayne the underrated actor (how anyone could watch Wayne’s performances in Stagecoach, They Were Expendable, The Searchers, True Grit, Island in the Sky, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon and The Quiet Man and still say he was “always the same” strikes me as a study in obtuseness, and I suspect Scott would feel the same way). The biography doesn’t shrink from an honest appraisal of the conservative politics that made Wayne such a hated lightning rod in the last third of his life, or the fact that he could be impatient, demanding, gregarious and charming — sometimes by turns, sometimes all at once. We also see the history buff who knew the American Civil War backward and forward, the collector who could discuss Asian or Native American art, and the “demon chess player” who could psych out an opponent as much as out-maneuver him on the board.

Last but never least, John Wayne: The Life and Legend shows us the man who loved everything about making movies, who was first on the set in the morning and the last to leave at night. And who loved to talk about movies, his own and other people’s. At one point, Scott quotes reporter Billy Wilkerson of the Hollywood Reporter, who sat in on a conversation between Wayne and director William Wellman in 1954, when the two were putting the finishing touches on The High and the Mighty: “They had praise for every name brought into the gab and, above all, praise for the business that made it possible for unknowns to become great personages in such a short span. They had logical excuses for some failures — theirs and others — with never a knock, never derision, always enthusiasm.”

That, I think, is the John Wayne I would like to have met. And thanks to Scott Eyman, I feel like I have.

Love all of Scott Eyman's books – his Lubitsch biography is beyond great – and since Wayne is one of my all-time favorite actors, I'm chomping at the bit to get it…just as soon as that income tax refund check shows up.

Okay. I'm sold.