Shirley Temple Revisited, Part 6

Our Little Girl

Our Little Girl

(released June 6, 1935)

I’m not going to spend a lot of time on Shirley’s next picture because…Well, if (as I said in Part 3) Now and Forever is a bit of a dud, Our Little Girl is a flat-out stinker. A country doctor (Joel McCrea) gets so wrapped up in his practice and his research that his wife (Rosemary Ames), feeling ignored, seeks comfort first in the company, then in the arms, of their bachelor neighbor (Lyle Talbot). Meanwhile, the doctor’s nurse (Erin O’Brien-Moore) nurses an unrequited love for him. Caught in the middle of all this, and neglected by both her parents, is the couple’s daughter (Shirley).

Shirley couldn’t save this one; nothing could. The script by Steven Avery and Allen Rivkin was an indigestible stew of sugar, soap and corn, and director John Robertson (a veteran whose credits went back to 1916) was utterly defeated by it. On the other hand, even a brilliant script couldn’t have survived Robertson’s leaden, clomping direction, which made the picture feel much longer than the 64 minutes it actually ran. Perhaps not incidentally, this was Robertson’s last movie, as it was for leading lady Rosemary Ames, whose two-year, eight-picture career ended here.

Shirley never made a worse movie, and neither did Joel McCrea. (Lyle Talbot did — but only because he made three pictures with Ed Wood.)

Variety’s reviewer “Odec” predicted (accurately) that “despite [the] story”, Shirley’s fans would make the picture profitable. At the New York Times, Andre Sennwald was less conciliatory: “As we have learned to expect, ‘Pollyanna’ and ‘The Bobsey Twins’ [sic] are classics of gutter realism by comparison with the sentimental syrups which Miss Temple’s impresarios arrange for the Baby Duse.“ Dyspeptic, yes, but Our Little Girl had it coming, and worse. (Mr. Sennwald still spoke fondly of Little Miss Marker, but he was clearly reaching a saturation point, if not with Shirley, at least with her vehicles. As fate would have it, he would review only two more of them — Curly Top and The Littlest Rebel, with increasing asperity — before dying in a gas-line explosion in his Manhattan penthouse on January 12, 1936; Sennwald was only 28.)

In Child Star, Shirley said of Our Little Girl, “I forgot it as soon as possible.” As well she might, but it wasn’t because of the picture itself; it was due to things that happened during shooting.

First: Shirley was going through the normal tooth losses of any kid her age, but shooting couldn’t be held up while they grew back, so she wore temporaries for the camera. One day on Our Little Girl‘s rural location, she sneezed two of hers out into a grassy meadow. The whole crew searched long through the grass, but to no avail, and the company had to wrap for the day while new ones were crafted for the little star. Shirley had conceived a girlish crush on Joel McCrea, and seeing his annoyance at the delay, she was accordingly chagrined.

But worse was to come; the very next day, Shirley’s chagrin turned to mortification. Standing with McCrea by a stream while lighting gaffers fiddled endlessly with their lights and reflectors, and with the long silence broken only by the trickle of the nearby brook, Shirley — there’s no gentle way to say it — wet her pants. Understandably, she immediately burst into tears. Mother Gertrude gently led her sobbing daughter to their trailer, where socks and undies were replaced, then Mother bucked up Shirley’s courage for the unavoidable return to the set. “Finally I mustered enough confidence to open the door,” Shirley wrote, “but only by convincing myself the whole thing had never happened.” She considered that moment her “Oscar performance”.

Poor Shirley. Even fifty-plus years on, writing in Child Star, her humiliation is still palpable. No wonder she forgot Our Little Girl without delay. We should too.

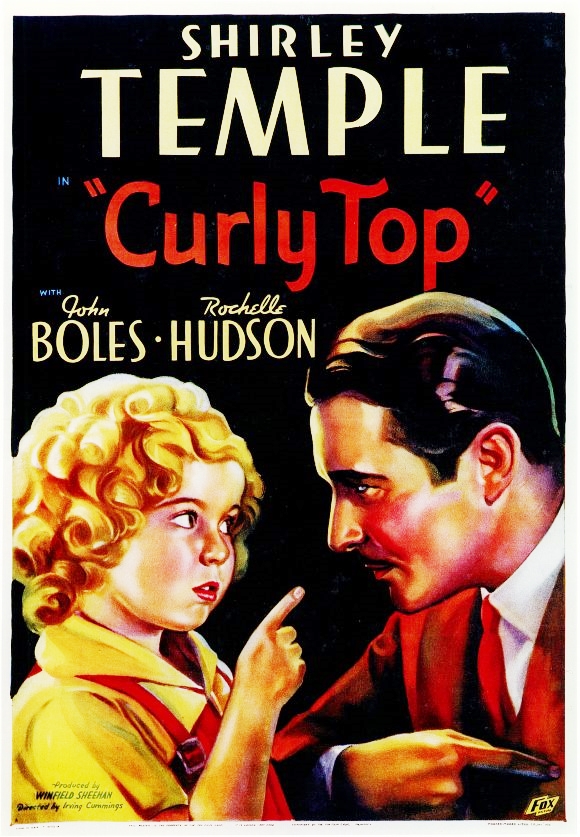

Curly Top

Curly Top

(released August 1, 1935)

Shirley plays Elizabeth “Curly” Blair, an orphan who charms Edward Morgan (John Boles), one of the rich trustees of the orphanage where she lives; Morgan legally adopts Curly while pretending to be acting on behalf of one “Hiram Jones.”

The story was a liberal reworking of Jean Webster’s 1912 novel Daddy Long Legs, which told of Judy Abbott, an orphan who, when she grows too old to stay at her orphanage, is sponsored through college by a benefactor who insists on remaining anonymous. By story’s end Judy learns that the mysterious “John Smith” is wealthy Jervis Pendleton, whom she knew (and had a girl’s crush on) from his visits to the orphanage. Now full-grown (and college educated), Judy marries him. Webster’s novel had already been filmed in 1919 with Mary Pickford and in 1931 with Janet Gaynor (and would be again in 1955, as a musical starring Fred Astaire and Leslie Caron). Since Fox had produced the 1931 version and still owned the screen rights to the story, they were at liberty to refashion it to fit Shirley.

Needless to say, if the boys at Fox couldn’t wait for Shirley’s adult teeth to grow in, they certainly couldn’t sit around while she reached an age to marry John Boles, so Patterson McNutt and Arthur Beckhard’s script supplied Curly with an older sister Mary (Rochelle Hudson) to be adopted with her and to discharge the romantic duties with the handsome Boles. Hudson and Boles even held up their end with the songs: Hudson, a neophyte singer, did quite well with “The Simple Things in Life” (by Edward Heyman and Ray Henderson), while Boles returned to his musical comedy roots with “It’s All So New to Me” (also by Heyman and Henderson) and the picture’s title song (Henderson and Ted Koehler).

But like the story, the supporting players (Boles; Hudson; Jane Darwell and Rafaela Ottiano as matrons at the orphanage; Esther Dale as Boles’s aunt; Billy Gilbert and Arthur Treacher as his cook and butler) were all beside the point. Shirley was just about the whole show. She is even the focus of both Boles’s songs. After singing “It’s All So New to Me”, while the orchestra wafts on in the background, he strolls around his palatial drawing room, where he fancies Shirley beaming down at him from the paintings on the walls…

But like the story, the supporting players (Boles; Hudson; Jane Darwell and Rafaela Ottiano as matrons at the orphanage; Esther Dale as Boles’s aunt; Billy Gilbert and Arthur Treacher as his cook and butler) were all beside the point. Shirley was just about the whole show. She is even the focus of both Boles’s songs. After singing “It’s All So New to Me”, while the orchestra wafts on in the background, he strolls around his palatial drawing room, where he fancies Shirley beaming down at him from the paintings on the walls…

Curly Top was Shirley’s last picture for Fox Film Corp., and her last with Winfield Sheehan, who had piloted her career since Stand Up and Cheer! As chief of production in the wake of William Fox’s personal and professional nosedive in 1929-30, Sheehan had managed to stave off the studio’s total financial collapse (largely through hanging on to Will Rogers and locking Shirley into a long-term contract), but the waters were still rocky. Even before Curly Top went into production, there were rumors of negotiations with the upstart Twentieth Century Pictures, a thriving new kid in town, but one in need of a studio complex and distribution system — one like Fox’s, for example. On May 29, 1935, a merger was announced; the new studio would be called 20th Century Fox. Less than two months later, Winfield Sheehan was out as head of production, replaced by the man who had spearheaded Twentieth Century to a success that entitled it to be senior partner in its merger with the more venerable Fox. The man, moreover, who would be in charge of Shirley’s career for the rest of the 1930s: Darryl F. Zanuck.

To be continued…

Little Shirley constantly amazes me. I'm enjoying your series very much.