Shirley Temple Revisited, Part 7

The creation of 20th Century Fox was announced as a merger, but it was really a friendly takeover. Darryl Zanuck (former production head at Warner Bros.) and Joseph Schenck (former president of United Artists) had formed 20th Century Pictures in 1933 as an independent concern, renting equipment and studio-and-office space from UA. In two years 20th Century had produced 18 pictures, all but one of which had made money, and several of which had made quite a lot: Folies Bergere de Paris, The House of Rothschild, The Affairs of Cellini, The Call of the Wild, Les Miserables, etc. But Zanuck got his hackles up when UA wouldn’t sell any of its stock to 20th Century, and he started looking around.

The creation of 20th Century Fox was announced as a merger, but it was really a friendly takeover. Darryl Zanuck (former production head at Warner Bros.) and Joseph Schenck (former president of United Artists) had formed 20th Century Pictures in 1933 as an independent concern, renting equipment and studio-and-office space from UA. In two years 20th Century had produced 18 pictures, all but one of which had made money, and several of which had made quite a lot: Folies Bergere de Paris, The House of Rothschild, The Affairs of Cellini, The Call of the Wild, Les Miserables, etc. But Zanuck got his hackles up when UA wouldn’t sell any of its stock to 20th Century, and he started looking around.

Enter Sidney Kent, president of Fox Film Corp. When Kent entered into merger negotiations with Zanuck and Schenck, he probably had visions of “Fox-20th Century Pictures”, thinking he was co-opting the rising competition and bringing a hot young producer into the Fox fold. But he didn’t figure on the drive and energy of Darryl F. Zanuck.

Neither did Winfield Sheehan. The Fox production chief knew there’d be room for only one chief at the new studio, and he braced himself for a struggle. But he was overmatched; Zanuck was younger, more aggressively ambitious — and, frankly, he had a better record at the box office. By the end of July 1935 Sheehan had taken a $420,000 buyout and left the company. Sidney Kent stayed on as president, at $180,000 a year, plus $25,000 as president of National Theatres Corp., Fox’s distribution affiliate. Just to show who 20th Century Fox’s real key figure was, Zanuck was made vice president in charge of production at $260,000 a year, plus ten percent of the gross on the pictures he supervised — plus enough stock in the company to ensure another $500,000 a year.

Such popularity did have its worrisome side, especially for Shirley’s parents; the kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby was still news. Their concern would be borne out during a radio broadcast on Christmas Eve 1939, when a woman in the audience, unhinged by grief, pointed a gun at Shirley, determined to kill the body that she believed had stolen the soul of her own dead daughter; the danger passed when the woman was seized and disarmed by two FBI agents who had been alerted to her suspicious presence. But that’s getting ahead of my story. For now, in 1935, the studio engaged burly John Griffith to serve as Shirley’s chauffeur and bodyguard (Shirley considered him a grown-up playmate). “Watch the kid like a hawk,” Zanuck told Griffith. “If anything happens to her, this studio might as well close up.”

The Littlest Rebel

(released December 19, 1935)

Shirley’s first picture to bear the new 20th Century Fox logo (with its now-famous fanfare) had been in the works before the merger, as the cover of this sheet music suggests. The ostensible source was a play by Edward Peple that ran for 55 performances on Broadway in the winter of 1911-12 before embarking on a long and prosperous tour, making a child star of the ill-fated Mary Miles Minter. The play had been filmed before in 1914, a version now presumed lost. (Playwright Peple, like The Little Colonel author Annie Fellows Johnston, did not live to see Shirley’s remake, having died of a heart attack in 1924, age 54.)

Shirley’s first picture to bear the new 20th Century Fox logo (with its now-famous fanfare) had been in the works before the merger, as the cover of this sheet music suggests. The ostensible source was a play by Edward Peple that ran for 55 performances on Broadway in the winter of 1911-12 before embarking on a long and prosperous tour, making a child star of the ill-fated Mary Miles Minter. The play had been filmed before in 1914, a version now presumed lost. (Playwright Peple, like The Little Colonel author Annie Fellows Johnston, did not live to see Shirley’s remake, having died of a heart attack in 1924, age 54.)But actually, that’s a bit of an overstatement. In fact, several of the characters’ names survived from stage to screen. Shirley plays Virginia Cary, a six-year-old resident of her namesake state whose birthday party is interrupted by news of the firing on Fort Sumter. Her father (John Boles) soon rides off to war, leaving the plantation in the hands of his wife (Karen Morley), little Virgie, and their loyal slaves, led by butler Uncle Billy (Bill Robinson) and his assistant James Henry (Willie Best). Late in the war, the Union Army sweeps through, and Virgie’s defiance earns the amused respect of Yankee Col. Morrison (Jack Holt). When Capt. Cary sneaks home to attend his wife’s deathbed and is captured, a sympathetic Morrison tries to help him and Virgie escape through Union lines, but father and daughter are caught and the two men are condemned to the firing squad — Capt. Cary for spying, Col. Morrison for aiding and abetting the enemy. Virgie and Uncle Billy rush to Washington, hoping to obtain a pardon from President Lincoln. I won’t say how this all turns out, but even if I did it would hardly amount to a surprise or a spoiler.

The Littlest Rebel was aimed at duplicating the success of The Little Colonel; in fact, it surpassed it, and was one of Shirley’s smoothest pictures. The only thing that really dates it today — and it dates it terribly — is the racial attitude I mentioned in my notes on The Little Colonel. That attitude is even more glaring and uncomfortable in The Littlest Rebel because the picture deals directly with the Civil War itself. When Edward Peple wrote his play in 1914, the war was well within human memory; even by the time the movie was made, that generation had not yet passed away (three years later, in 1938, the 75th anniversary of the battle of Gettysburg would occasion a reunion of nearly 1,900 Civil War veterans). The Old South with its genteel planter aristocracy and loyal, happy, contented slaves was an article of faith in the Myth of the Lost Cause, one that died hard and bitterly, and it’s on full display in The Littlest Rebel. It’s difficult to argue with modern viewers who find it just too hard to take. (Shirley even plays one scene in blackface disguise, though at least we are spared the sorry spectacle of hearing her speak with a “darkie” accent.)

The Littlest Rebel was aimed at duplicating the success of The Little Colonel; in fact, it surpassed it, and was one of Shirley’s smoothest pictures. The only thing that really dates it today — and it dates it terribly — is the racial attitude I mentioned in my notes on The Little Colonel. That attitude is even more glaring and uncomfortable in The Littlest Rebel because the picture deals directly with the Civil War itself. When Edward Peple wrote his play in 1914, the war was well within human memory; even by the time the movie was made, that generation had not yet passed away (three years later, in 1938, the 75th anniversary of the battle of Gettysburg would occasion a reunion of nearly 1,900 Civil War veterans). The Old South with its genteel planter aristocracy and loyal, happy, contented slaves was an article of faith in the Myth of the Lost Cause, one that died hard and bitterly, and it’s on full display in The Littlest Rebel. It’s difficult to argue with modern viewers who find it just too hard to take. (Shirley even plays one scene in blackface disguise, though at least we are spared the sorry spectacle of hearing her speak with a “darkie” accent.)

So: The Littlest Rebel has Willie Best’s James Henry to neutralize (if not nullify) the humanity of Bill Robinson’s Uncle Billy — rather than complement and reinforce it, as Hattie McDaniel’s Mom Beck had done in The Little Colonel. Plus a slave population so happy in bondage that they have no interest in emancipation and don’t even understand what it is. With all that, it’s not surprising that many viewers prefer not to watch the picture today — much less show it to children who can’t place it in its proper historical context.

Variety’s reviewer “Land” pegged The Littlest Rebel exactly, noting its striking similarity to The Little Colonel, yet conceding that it probably “won’t dampen the enthusiasm of the Temple worshippers…All bitterness and cruelty has been rigorously cut out and the Civil War emerges as a misunderstanding among kindly gentlemen with eminently happy slaves and a cute little girl who sings and dances through the story…Story is synthetic throughout but smart showmanship instills the illusion of life.” In the New York Times, Andre Sennwald agreed: “You may have got the mistaken notion from ‘So Red the Rose’ [a Civil War melodrama released the month before] that the war between the States was filled with ruin, death, rebellious slaves and horrid Yankee barbarians. ‘The Littlest Rebel’ corrects that unhappy thought and presents the conflict as a decidely chummy little war…As Uncle Billy, the faithful family butler, Bill Robinson is excellent, and some of the best moments in ‘The Littlest Rebel’ are those in which he breaks into song and dance with Mistress Temple.”

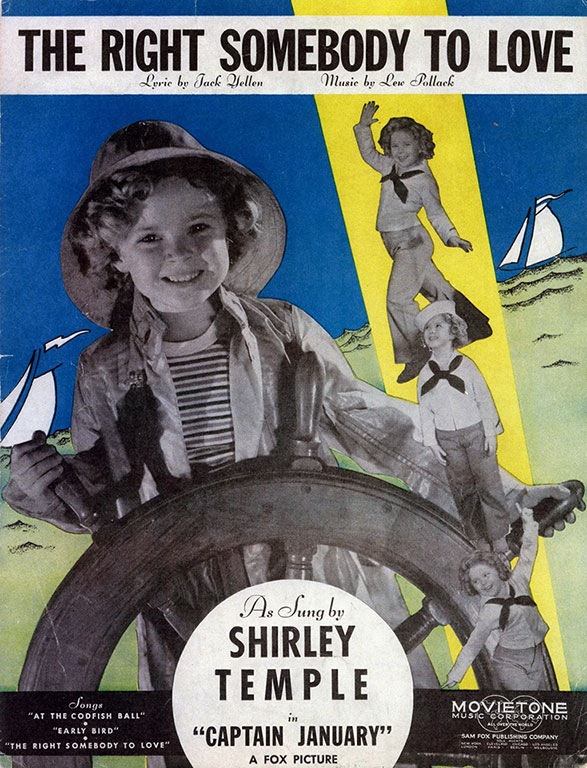

Captain January

(released April 24, 1936)

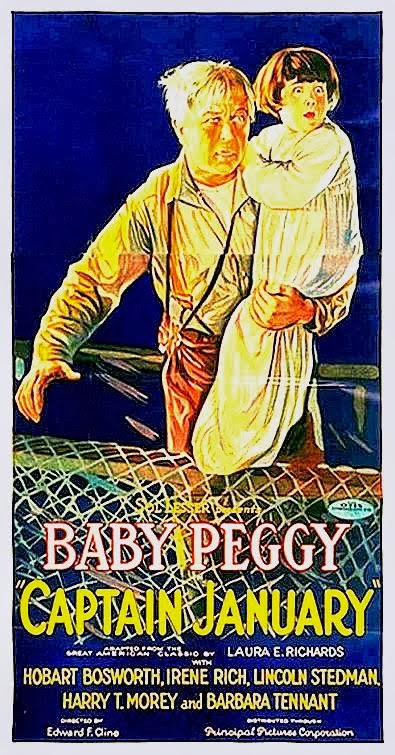

Captain January seems to have a special place in the hearts of Baby Boomers of a Certain Age, perhaps because it was one of Shirley Temple’s first features to go into television syndication in the 1950s. The source material was an 1891 novella by Laura E. Richards. Born Laura Elizabeth Howe in 1850, Mrs. Richards was the daughter of Julia Ward Howe, author of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”. A prolific author in her own right, Mrs. Richards wrote over 90 books, including, with her sister Maud Howe Elliott, a biography of their mother that won them a Pulitzer Prize in 1917. Mrs. Richards also wrote the children’s nonsense poem “Eletelephony” (“Once there was an elephant,/Who tried to use the telephant –/No! No! I mean an elephone,/Who tried to use the telephone…”). Unlike the authors of The Little Colonel and The Littlest Rebel, she lived long enough to see two movies made from her modest little story, dying in 1943 at 92. Whether she saw either movie, or what she thought of them, is not recorded.

Captain January seems to have a special place in the hearts of Baby Boomers of a Certain Age, perhaps because it was one of Shirley Temple’s first features to go into television syndication in the 1950s. The source material was an 1891 novella by Laura E. Richards. Born Laura Elizabeth Howe in 1850, Mrs. Richards was the daughter of Julia Ward Howe, author of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”. A prolific author in her own right, Mrs. Richards wrote over 90 books, including, with her sister Maud Howe Elliott, a biography of their mother that won them a Pulitzer Prize in 1917. Mrs. Richards also wrote the children’s nonsense poem “Eletelephony” (“Once there was an elephant,/Who tried to use the telephant –/No! No! I mean an elephone,/Who tried to use the telephone…”). Unlike the authors of The Little Colonel and The Littlest Rebel, she lived long enough to see two movies made from her modest little story, dying in 1943 at 92. Whether she saw either movie, or what she thought of them, is not recorded.

Mrs. Richards’s Captain January is a short-and-bittersweet tale of a retired old seafarer, one Januarius Judkins (“Captain January”), who lives alone tending a lighthouse on a small island off the rugged coast of Maine.

One night during a terrible storm he sees a ship founder in the rocky sea around his island. Venturing out in search of possible survivors, he finds only one, an infant girl clutched in her dead mother’s arms. He retrieves the child and several corpses, including both the baby’s parents. The anonymous dead he gives a decent burial on his island, the orphan girl he takes to shelter in his lighthouse. The next day a trunkfull of clothing belonging to the infant’s mother washes up on shore, but it contains no hint of the dead parents’ identities beyond some embroidered initials. With no way of knowing the baby’s name or family, he raises the girl himself, naming her Star Bright.

Ten years later, a woman on a passing cruise ship catches a glimpse of Star and is convinced she is the daughter of her dead sister, lost at sea with her husband and child while sailing home from Europe ten years earlier. It’s soon established beyond doubt that Star is Isabel Maynard, the long lost and presumed dead niece of that cruise ship passenger, Mrs. Morton. At first, Mrs. Morton wishes to take the girl to live with her, with full gratitude to Captain January for rescuing and raising her. But when she sees how it will break the hearts of both Star and the captain, she relents, and lovingly leaves the girl with the only father she’s ever known.

Even so, Captain January knows that his days on earth are nearly done, and he arranges with his friend, sailor Bob Peet, to keep an eye on the lighthouse whenever he sails by: If the little blue flag is flying, all is well; if the flag has been struck, it’s time for Bob to come and collect Star, and to take her to live with the Mortons, who will welcome her as one of their own — which in fact she is. Finally, in the spring of the following year, January feels his heart failing, and with his last ounce of strength he hauls down the little flag, then returns to his favorite chair to wait. “For Captain January’s last voyage is over, and he is already in the haven where he would be.”

Both Abel Green in Variety and Frank S. Nugent in the New York Times found Captain January to be “okay film fare” (Green) despite the “moss-covered script” (Nugent). One of the most interesting reviews came from across the Pond, where Graham Greene, writing in the London Spectator, found the picture to be “a little depraved, with an appeal interestingly decadent…Shirley Temple acts and dances with immense vigor and assurance, but some of her popularity seems to rest on a coquetry quite as mature as Miss [Claudette] Colbert’s, and on an oddly precocious body, as voluptuous in grey flannel trousers as Miss [Marlene] Dietrich’s.” Greene would pursue that line of thought in subsequent reviews, and would in time catch the gimlet eye of 20th Century Fox’s legal department. But I’ll get to that in its turn.

For the record, just in case you’ve lost track, Shirley was now seven years old; her eighth birthday was the day before Captain January opened in New York. Of course, hardly anybody besides her parents knew that; the rest of the world — including Shirley herself — thought she had just turned seven.

Next time: Fox’s top two female stars go head-to-head.

To be continued…

Reading this series, I'm realizing just how young I was when I first saw these movies…I never connected Jack Holt with Colonel Morrison, even though I've seen him in several movies since.

I was a history buff even as a kid, though, and it always amused me a little how The Littlest Rebel got from Sumter to Sheridan in about 30 seconds, without Virgie getting any older. 🙂