Day 3

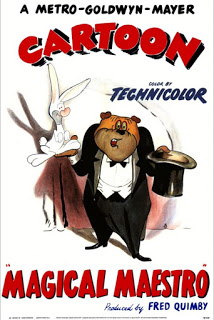

Another regular — and eagerly anticipated — feature of Cinevent is the Saturday morning cartoon program, compiled and curated by animation maven Stewart McKissick. This year the bill included a specimen from each of the major cartoon studios of the 1930s through ’50s — Disney, Warner Bros., MGM, Fleischer, UPA, etc. The clear highlight of the morning was MGM’s Magical Maestro (1952) by the great Tex Avery, in which a spurned vaudeville magician wreaks vengeance by disrupting an operatic recital by “the Great Poochini” (as the poster shows, the cartoon is populated by dogs). It’s a wild and zany ride that anticipates (may even have inspired) Chuck Jones’s Duck Amuck over at Warners the following year, and it’s better seen than described.

Fortunately, that can be arranged. Click here to see the cartoon complete from beginning to end — including a few fleeting (and fairly harmless) seconds of non-p.c. ethnic humor. It’s only six-and-a-half minutes, and worth the side trip. I’ll wait till you get back. (NOTE: The cartoon is on a Romanian-language Web site and is preceded by a commercial for one product or another. Look for a white “X” in the top right corner of the frame or the word “Inchide” [“skip”] in the bottom right; click on either of those and it’ll go directly to the cartoon.)

The cartoon program was followed by Houdini (1953), a purported biopic starring a youthful Tony Curtis and then-wife Janet Leigh as the legendary escapologist and his wife Bess. A big hit in 1953, the picture was a mainstay of Saturday afternoon kiddie matinees when I was going to them — I remember seeing it three or four times — and I’ve always had a soft spot for it. There was, of course, a magician and escape artist (born Erik Weisz) who billed himself as Harry Houdini, and his wife Wilhelmina Beatrice was known as Bess; aside from that, the movie is arrant fiction from first frame to last — but it’s as entertaining as it is made-up. Seeing it in Columbus this year — especially right after a whole slew of cartoons — made me feel seven years old again.

The afternoon was devoted to two silent programs: Douglas Fairbanks in His Picture in the Papers (1916), followed by a selection of rarely seen comedy shorts, also from 1916, consisting of The Mystery of the Leaping Fish, starring Doug Fairbanks again as a detective named (get this) Coke Ennyday (a spoof on the name of Craig Kennedy, a character created by Arthur B. Reeve in 1910 and popular in magazine fiction until Reeve’s death in 1936); An Angelic Attitude, directed by and starring Tom Mix, already seven years into his movie career and poised on the brink of superstardom; and A Scoundrel’s Toll, a Mack Sennett short starring Raymond Griffith. (Griffith would be a mid-level comedy star throughout the 1920s, but his badly damaged vocal cords would relegate him to behind-the-camera work writing and producing, and quite successfully, once talkies came in.)

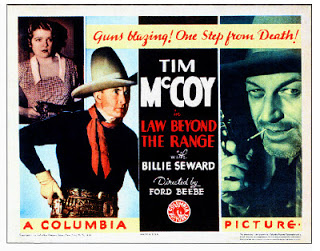

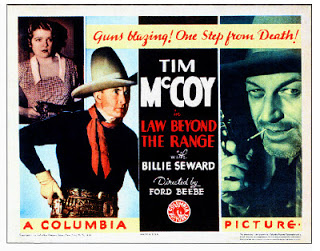

This was followed by Tim McCoy in

Law Beyond the Range (1935), an unpretentious and quite entertaining B western from Columbia. Tim McCoy was one of those interesting characters who sort of backed into movies because making movies was fun and he himself was fairly comfortable in front of camera. Born in Saginaw, Michigan, in 1891, he became fascinated with the Wild West as a student in college; he dropped out and resettled in Wyoming, where he became a ranch hand and expert horseman. After serving in World War I (he rose to the rank of colonel and later, in his movie career, was sometimes billed as Col. Tim McCoy), he was appointed adjutant general of the Wyoming National Guard. In that capacity he worked diplomatically and well with Wyoming’s native Arapaho and Shoshone tribes, and in 1922, when Paramount came to Wyoming to film their epic

The Covered Wagon, McCoy served as liaison between the company and several hundred Indian extras. That gave him the bug. He resigned his commission and cried “Westward ho!” once again, settling in Hollywood, where he worked steadily through the 1940s, then tapered off into retirement, making his last appearance in

Requiem for a Gunfighter in 1965.

In Law Beyond the Range McCoy played a Texas Ranger who leaves the force to take over an old friend and mentor’s crusading newspaper in a neighboring town. Arriving in town shortly after his editor friend’s death, he carries on the paper’s crusade against the crime boss who is running the town (Guy Usher). In the end he brings down the bad guy, but not because the pen is mightier than the sword; in fact it takes a blazing shootout that fills the local saloon with a dense cloud of gunsmoke, a rip-roaring climax that Col. Tim’s 1935 fans had no doubt been waiting for all along. At the final fadeout he has not only cleaned up the town but cleared an old friend (Robert Allen) of a bogus murder charge and won the heart of the late editor’s daughter (Billie Seward).

After dinner came of two of the highlights of the whole weekend — both, as it happened, from Universal. First was

California Straight Ahead (1937). I here reproduce the title card from the movie’s credits, rather than a poster or lobby card, to make a point: It’s 1937, two years before

Stagecoach, and John Wayne is billed

above the title. And not in a B western from Monogram or Republic, but in one of six pictures he made at Universal (none of them westerns) before returning to the saddle at Republic. It’s still a B picture, of course; it would take John Ford to promote the Duke out of B’s once and for all. But

California Straight Ahead has a better-than-B professional gloss to it; with Universal’s backlot and production infrastructure a few dollars could go a lot farther than they could on some location ranch up in the San Fernando Valley.

Wayne plays a partner in a struggling Chicago trucking firm, trying to make a go of his little two-truck operation against sometimes unscrupulous opposition from other truckers and railroads (he faces some unsporting competition for the affections of the fetching Louise Latimer too). The story climaxes in a cross-country race between Wayne’s convoy of big-rigs and an express train, both seeking to deliver a shipment of airplane parts to the Port of Los Angeles to be loaded on a ship and dispatched across the Pacific before a general strike closes the port. With a smart script by W. Scott Darling and lickety-split direction by Arthur Lubin, the picture makes for an enjoyable 67 minutes.

In his introduction to the screening, Wayne biographer Scott Eyman told us that Wayne regarded his six-picture foray at Universal as a mistake; it had failed to take him out of the “juvenile ghetto” of Saturday afternoon B westerns, and when it was over he found himself back at Square One in Republic horse operas — without his former momentum and unsure when, or if ever, he could work his way out of them. (He couldn’t know, of course, that his big break was just around the corner.) I quote Scott at length on California Straight Ahead and the Duke’s five other Universal B’s: “This is a good movie; they are all good, solid movies. They’re better, frankly, I think, than the Republic westerns he’d been making, because the technicians are a little bit better, the scripts are a little bit better, and the production schedules a little bit longer, and you can get more of where he’s not just riding and roping and slugging people. He actually gets a chance to do a little acting in these movies. And as you’ll see, he’s getting better and better. By 1937, and finishing up this series of pictures, he’s ready. He’s ready for John Ford, he’s ready for the Big Time.”

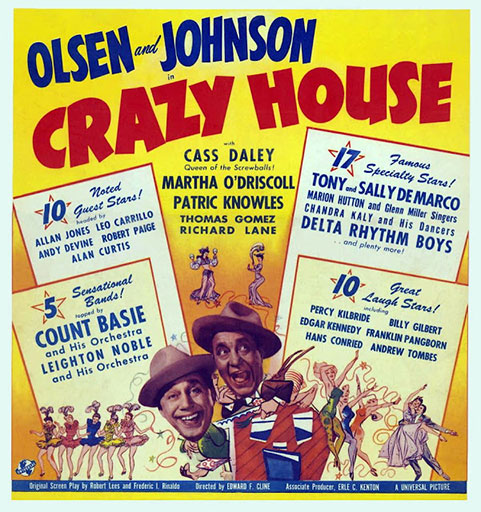

And then came the deluge, again courtesy of Universal Pictures. The title of this onslaught was

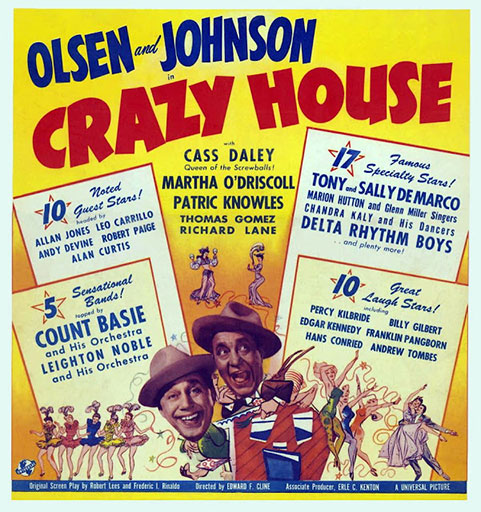

Crazy House, and the leading inmates of the loony bin were two slap-happy vaudevillians named Ole Olsen and Chic Johnson. How do you describe these two to someone who’s never seen them? In my last post I called them the Monty Python of the 1940s, but the truth is, Olsen and Johnson made Monty Python look like a Sunday afternoon game of whist between Oscar Wilde and James MacNeill Whistler.

John Sigvard “Ole” Olsen and Harold Ogden “Chic” Johnson first teamed up in 1914 as members of a more or less straight musical vaudeville quartet. Their personalities and wacky senses of humor clicked, and they eventually morphed into a madcap improvisational comedy act, with neither of them playing the customary straight man. Eventually they wound up on radio in “The Padded Cell of the Air”, a segment of NBC’s Fleischmann’s Yeast Hour, hosted by crooner Rudy Vallee. The rather stodgy Vallee evidently left Olsen and Johnson pretty much to their own devices, and the team’s wild act was free-wheeling and utterly unpredictable. They reached their apotheosis in 1938 with the Broadway musical comedy revue Hellzapoppin, whose title remains a byword for insanely corny, anything-for-a-laugh comedy. It was a show where nobody ever knew what was going to happen next. And I don’t mean just the audience — I mean the stagehands, the orchestra and the other performers. Hellzapoppin ran for over three years — 1,404 performances, and it was never the same experience twice.

In 1941 Universal induced Olsen and Johnson to put the show on film (as Hellzapoppin’, adding the apostrophe). It might have seemed like a fool’s errand, and Universal hedged their bets by forcing the insertion of a conventional romantic subplot, but the movie clicked. It was screened at last year’s Cinevent and stole the whole weekend, as hilarious as ever.

And so it was this year with Crazy House, Olsen and Johnson’s follow-up movie two years later. It begins with Olsen and Johnson staging their own triumphant return parade down Hollywood Boulevard, with the cry preceding them: “Olsen and Johnson are coming!”, while everyone from studio bigwigs to hairdressers and carpenters flies into a panic. (On one soundstage Basil Rathbone tells Nigel Bruce of the dire devastation in store for them all when the two comics arrive. “How do you know all that?” Bruce asks. “I’m Sherlock Holmes,” snaps Rathbone. “I know everything.”) The boys show up to find the Universal lot deserted and barricaded against them. Unfazed, they resolve to produce their next movie themselves.

Let’s leave it at that, shall we? Crazy House goes on in that vein for a lightning 80 minutes, throwing jokes so fast you miss every third one because you’re still laughing at the first two. Olsen and Johnson’s governing principle was that a joke not good enough to use once might be bad enough to use five times, and it still works; O&J’s influence can be seen not only in Monty Python but elsewhere, including Laugh-In in the 1960s and Jim Henson’s original Muppet Show 20 years after that.

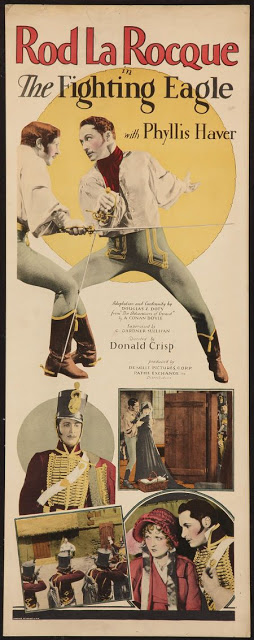

After the boisterous delirium of Crazy House anything would have been an anticlimax, so 1927’s silent The Fighting Eagle started off at a disadvantage. Still, it was an engaging, slightly tongue-in-cheek swashbuckler with Rod La Rocque (such a perfectly Hollywood name, and yet it was his own) swaggering grandly as a braggart popinjay French soldier engaging in swordplay, intrigue and romance (with countess Phyllis Haver, the movies’ original Roxie Hart in Chicago) in the days of the Emperor Napoleon.

And finally, another midnight snack: The Monkey’s Paw, a low-budget 1948 British thriller with a good but uniformly unfamiliar cast, adapted from the classic short story by W.W. Jacobs. If you haven’t read the story, you should; give yourself a sleepless night or two. It concerns the eponymous, mummified simian extremity, a talisman with the power to grant three wishes. But this monkey’s paw is no rabbit’s foot; it’s the ultimate illustration of be-careful-what-you-wish-for: In a touch not in the original story but added for the movie, one woman wishes to be free of her boring, alcoholic husband; her freedom is granted to her when he shoots her dead.

Jacobs’s story is a vivid one, but short, and the

script by Barbara Toy and director Norman

Lee fills it out without diluting its sinister

spirit — as that flashback scene with the bored

wife makes clear. And so it was, at 2:00 that

Sunday morning, after the monkey’s paw had

wrought its dark magic on the hapless

Trelawne family (played by Milton Rosmer,

Megs Jenkins and Eric Micklewood), that

those hardy night owls among us were

finally trundled off to our rooms, our lights,

and the comforting drone of an all-night

television…

To be concluded…

This was followed by Tim McCoy in Law Beyond the Range (1935), an unpretentious and quite entertaining B western from Columbia. Tim McCoy was one of those interesting characters who sort of backed into movies because making movies was fun and he himself was fairly comfortable in front of camera. Born in Saginaw, Michigan, in 1891, he became fascinated with the Wild West as a student in college; he dropped out and resettled in Wyoming, where he became a ranch hand and expert horseman. After serving in World War I (he rose to the rank of colonel and later, in his movie career, was sometimes billed as Col. Tim McCoy), he was appointed adjutant general of the Wyoming National Guard. In that capacity he worked diplomatically and well with Wyoming’s native Arapaho and Shoshone tribes, and in 1922, when Paramount came to Wyoming to film their epic The Covered Wagon, McCoy served as liaison between the company and several hundred Indian extras. That gave him the bug. He resigned his commission and cried “Westward ho!” once again, settling in Hollywood, where he worked steadily through the 1940s, then tapered off into retirement, making his last appearance in Requiem for a Gunfighter in 1965.

This was followed by Tim McCoy in Law Beyond the Range (1935), an unpretentious and quite entertaining B western from Columbia. Tim McCoy was one of those interesting characters who sort of backed into movies because making movies was fun and he himself was fairly comfortable in front of camera. Born in Saginaw, Michigan, in 1891, he became fascinated with the Wild West as a student in college; he dropped out and resettled in Wyoming, where he became a ranch hand and expert horseman. After serving in World War I (he rose to the rank of colonel and later, in his movie career, was sometimes billed as Col. Tim McCoy), he was appointed adjutant general of the Wyoming National Guard. In that capacity he worked diplomatically and well with Wyoming’s native Arapaho and Shoshone tribes, and in 1922, when Paramount came to Wyoming to film their epic The Covered Wagon, McCoy served as liaison between the company and several hundred Indian extras. That gave him the bug. He resigned his commission and cried “Westward ho!” once again, settling in Hollywood, where he worked steadily through the 1940s, then tapered off into retirement, making his last appearance in Requiem for a Gunfighter in 1965. After dinner came of two of the highlights of the whole weekend — both, as it happened, from Universal. First was California Straight Ahead (1937). I here reproduce the title card from the movie’s credits, rather than a poster or lobby card, to make a point: It’s 1937, two years before Stagecoach, and John Wayne is billed above the title. And not in a B western from Monogram or Republic, but in one of six pictures he made at Universal (none of them westerns) before returning to the saddle at Republic. It’s still a B picture, of course; it would take John Ford to promote the Duke out of B’s once and for all. But California Straight Ahead has a better-than-B professional gloss to it; with Universal’s backlot and production infrastructure a few dollars could go a lot farther than they could on some location ranch up in the San Fernando Valley.

After dinner came of two of the highlights of the whole weekend — both, as it happened, from Universal. First was California Straight Ahead (1937). I here reproduce the title card from the movie’s credits, rather than a poster or lobby card, to make a point: It’s 1937, two years before Stagecoach, and John Wayne is billed above the title. And not in a B western from Monogram or Republic, but in one of six pictures he made at Universal (none of them westerns) before returning to the saddle at Republic. It’s still a B picture, of course; it would take John Ford to promote the Duke out of B’s once and for all. But California Straight Ahead has a better-than-B professional gloss to it; with Universal’s backlot and production infrastructure a few dollars could go a lot farther than they could on some location ranch up in the San Fernando Valley. And then came the deluge, again courtesy of Universal Pictures. The title of this onslaught was Crazy House, and the leading inmates of the loony bin were two slap-happy vaudevillians named Ole Olsen and Chic Johnson. How do you describe these two to someone who’s never seen them? In my last post I called them the Monty Python of the 1940s, but the truth is, Olsen and Johnson made Monty Python look like a Sunday afternoon game of whist between Oscar Wilde and James MacNeill Whistler.

And then came the deluge, again courtesy of Universal Pictures. The title of this onslaught was Crazy House, and the leading inmates of the loony bin were two slap-happy vaudevillians named Ole Olsen and Chic Johnson. How do you describe these two to someone who’s never seen them? In my last post I called them the Monty Python of the 1940s, but the truth is, Olsen and Johnson made Monty Python look like a Sunday afternoon game of whist between Oscar Wilde and James MacNeill Whistler.