Cinevent 2017 — No. 49 and Counting, Part 3

Day 3 — Saturday

Saturday morning, of course, is Cartoon Day at Cinevent — or at least it has been for the 20 years I’ve been going. This year was, in fact, the 28th annual animation program, once again assembled and curated by Stewart McKissick, whose depth of knowledge is as priceless as the toons he shows. This year the theme, insofar as there was one, was (I guess you could say) “Maiden Voyages” — that is, none of the ten cartoons on the program had ever played Cinevent before.

As you might expect, this made for quite a mixed bag: Neptune Nonsense (1936), a Felix the Cat cartoon (in Technicolor for a change) in which Felix gets in trouble with King Neptune when he tries to “fishnap” a companion for his lonely goldfish at home; Daffy Duck in Hollywood (1938), where the duck at his daffiest crashes the gates at Warner Bros. and revolutionizes the movie business; Ground Hog Play, a Casper the Friendly Ghost toon from 1956 (personally, I could always take but would prefer to leave Casper alone); and so on.

As you might expect, this made for quite a mixed bag: Neptune Nonsense (1936), a Felix the Cat cartoon (in Technicolor for a change) in which Felix gets in trouble with King Neptune when he tries to “fishnap” a companion for his lonely goldfish at home; Daffy Duck in Hollywood (1938), where the duck at his daffiest crashes the gates at Warner Bros. and revolutionizes the movie business; Ground Hog Play, a Casper the Friendly Ghost toon from 1956 (personally, I could always take but would prefer to leave Casper alone); and so on.

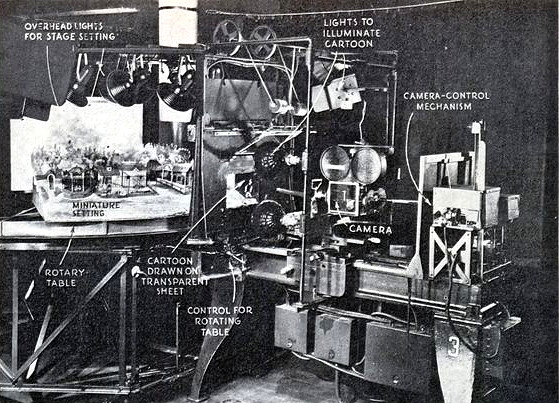

But I want to focus on one in particular: Musical Memories (1935), one of Max and Dave Fleischer’s two-color Technicolor pictures (at the time Disney had an exclusive contract to use the perfected three-strip Tech). The interest in this one (besides the color) is how it showcases Fleischer’s “setback” process. Like Disney’s multiplane camera (and developed at roughly the same time), the setback was designed to add dimensionality and visual interest to animation. Here’s an illustration of how it worked. Moving from right to left, you can see the camera (along with its control mechanism), then the central frame where the animation cels would be mounted (with attendant light fixtures), and finally the miniature three-dimensional set (also well-lit) that served as a background to the animated characters — hence the term “setback”. The set would be on a turntable that could be rotated as the characters “walked” back and forth on it. Sometimes the set would be painted with the same paints as the cel characters, sometimes with more realistic pigments, but either way it lent a striking three-dimensional look to Fleischer’s cartoons (a pity, says I, that Fleischer didn’t use the setback camera in his Superman series).

This 3-D effect was particularly apt in Musical Memories, since the premise was a sweet old couple in rocking chairs who “forget the swiftly moving tempos of the present” by dusting off their old stereopticon viewer while the soundtrack blooms with popular songs of their Gay Nineties youth — “I Wandered Today to the Hill, Maggie”, “Sidewalks of New York”, “Little Annie Rooney”, “After the Ball” and so on. It’s a charming variation on Fleischer’s follow-the-bouncing-ball cartoons, and if you know the songs I’ll bet you’ll find yourself humming along, if only in your head:

Last year at Cinevent, the Saturday animation program was followed by producer George Pal’s Houdini (1953) with Tony Curtis and Janet Leigh, which took me back to my childhood and the kiddie matinees at the Stamm Theatre in Antioch, Calif. There was more than one Saturday, and probably more than two, when an hour-and-a-half of cartoons was followed by Houdini. Well, danged if I didn’t get exactly that same sense of déjà vu this year — another passel of cartoons, another George Pal. This time it was When Worlds Collide (1951), from the 1932 Edwin Balmer/Philip Wylie novel about two rogue planets on a collision course with Earth, and the desperate efforts to build a spaceship to transport a sampling of humanity to one of the (apparently habitable) planets before the home world is obliterated.

Last year at Cinevent, the Saturday animation program was followed by producer George Pal’s Houdini (1953) with Tony Curtis and Janet Leigh, which took me back to my childhood and the kiddie matinees at the Stamm Theatre in Antioch, Calif. There was more than one Saturday, and probably more than two, when an hour-and-a-half of cartoons was followed by Houdini. Well, danged if I didn’t get exactly that same sense of déjà vu this year — another passel of cartoons, another George Pal. This time it was When Worlds Collide (1951), from the 1932 Edwin Balmer/Philip Wylie novel about two rogue planets on a collision course with Earth, and the desperate efforts to build a spaceship to transport a sampling of humanity to one of the (apparently habitable) planets before the home world is obliterated.

When Worlds Collide still has its cult following, but the truth is, of George Pal’s trilogy of 1950s sci-fi classics — Destination Moon (1950), WWC, and The War of the Worlds (1953) — this one has aged the least gracefully. Part of the reason is the leading man, Richard Derr, who bears a disconcerting resemblance to Danny Kaye, but with a veneer of off-putting smarm — a combination that helped keep his long career from ever really going anyplace. Partly it’s the dated science, and partly the dated fiction, with Sidney Boehm’s Bible-thumping script hitting us over the head with its Noah’s Ark analogies. And I suppose it doesn’t help that when the survivors of Earth step off their rocket ship they seem to have landed in the Pastoral Symphony set from Walt Disney’s Fantasia. For all that, though, the movie’s Oscar-winning special effects still deliver the goods, and 1950s nostalgia can cover a multitude of sins — especially when a print gleams with that gorgeous Paramount Technicolor, as this one did.

(Now, while I’m at it, if any of the Cinevent movers and shakers happen to be reading this, I’d like to put in a request. Let’s keep this cartoons-and-a-George-Pal-feature business going for one more year. Next year, Cinevent’s 50th, why not follow the Saturday animation program with The War of the Worlds? It’s not only Pal’s undeniable masterpiece, it’s one of the most beautifully-photographed movies of the entire decade. Plus, it’ll allow me one more nostalgia trip back to the kiddie matinees of my youth.)

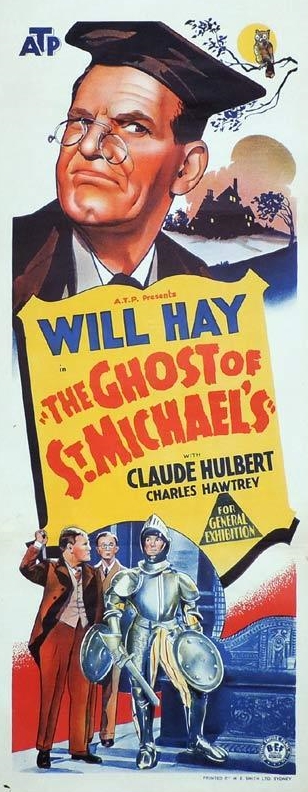

After the lunch break I had a chance to plug one of those gaps in my movie experience that has always kind of bugged me: I finally got to see a Will Hay movie, The Ghost of St. Michael’s (1941).

After the lunch break I had a chance to plug one of those gaps in my movie experience that has always kind of bugged me: I finally got to see a Will Hay movie, The Ghost of St. Michael’s (1941).

Will Hay is a name that mean absolutely nothing to Americans, but Britons of a certain age remember him with warmth and affection. After a career in British music halls playing a pompous, incompetent schoolmaster, he transferred the character to movies — not always a schoolmaster and not always with the same name, but the pompousness and incompetence remained constant. He made only 18 features before his untimely death (age 60) in 1949, but while he lasted he was one of the most popular stars in British pictures (he placed third behind George Formby and Gracie Fields). In the 1988 edition of The Filmgoer’s Companion author Leslie Halliwell appointed Hay to Halliwell’s Hall of Fame “For developing an unforgettable comic persona which lives in the memory independently of his films; and for persuading us to root for that character despite its basically unsympathetic nature.”

Judging just from The Ghost of St. Michael’s, I suspect that that “basically unsympathetic nature” business was strictly pro forma; Halliwell finds him unsympathetic because he should find him unsympathetic. But Will Lamb — the name Hay’s blustering schoolteacher takes this time around — is almost entirely likeable, and funny besides. The plot has to do with a boys’ school evacuated during the Blitz to a reputedly haunted castle on the Isle of Skye, the sound of ghostly bagpipes heralding a couple of mysterious deaths, and (spoiler alert!) the workings of a German spy lurking in the castle — who nevertheless proves to be no match for Master Lamb, his equally dim sidekick (Claude Hulbert) and a precocious student (Charles Hawtrey), who together manage to unravel the picture’s neat little mystery in fairly short order and very funny fashion.

The Ghost of St. Michael’s made for an auspicious introduction to the redoubtable Mr. Hay, and I was able to score a DVD of the picture in the Cinevent Dealers’ Room, along with three other titles: Boys Will Be Boys (1935), Where There’s a Will (’36) and Ask a Policeman (’39). Haven’t checked out any of those yet, but I’m looking forward to it.

And oh, by the way: Will Hay wasn’t nearly as dimwitted as the character he created on the music hall stage and British screens. He became fluent in French, Italian and German before he was out of his teens, and he was a respected amateur astronomer and Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society, having discovered a great white spot on the planet Saturn in 1933. The asteroid 3125 Hay was named in his honor.

Next came The Square Deal Man (1917), with William S. Hart as a gambler named Jack O’Diamonds, reformed by a saintly preacher and (particularly) his own admiration for a good woman (Mary McIvor), with an adorable little orphan (Mary Jane Irving) thrown in for good measure. This was followed by Clancy Street Boys (1943), a comedy programmer from Poverty Row’s Monogram Pictures starring Leo Gorcey, Huntz Hall and Bobby Jordan, billed here as the East Side Kids, midway through their transition from the Dead End Kids to the Bowery Boys. Gorcey’s daughter, Brandy Gorcey Ziesemer, was there in Columbus to introduce the picture and, with author Leonard Getz, to sign copies of From Broadway to the Bowery: A History and Filmography of the Dead End Kids, Little Tough Guys, East Side Kids and Bowery Boys Films, with Cast Biographies.

Also in Columbus for book signings, by the way, were Cinevent regular Scott Eyman (I picked up a copy of his 1990 Mary Pickford biography and his latest book with Robert Wagner, I Loved Her in the Movies: Memories of Hollywood’s Legendary Actresses); Richard Barrios (A Song in the Dark: The Birth of the Musical Film and Dangerous Rhythms: Why Movie Musicals Matter); Robert Matzen (Mission: Jimmy Stewart and the Fight for Europe); and John McElwee (The Art of Selling Movies, his worthy follow-up to Showmen, Sell It Hot!).

But back to the film program. In my last post I mentioned a near-lost Laurel and Hardy classic. This was The Battle of the Century (1927), Hal Roach’s second teaming of Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, and the one that set the mold for The Boys (Putting Pants on Philip stars Laurel and Hardy, but it’s not really a Laurel and Hardy film in the sense we understand today). This is the short with the famous pie fight, as illustrated on this poster. The title, however, refers not to that but to the first reel of the picture, which consists of a boxing match pitting puny prizefighter Stan agains a mountainous opponent named Thunder-Clap Callahan (Noah Young), with Ollie as his manager — and the outcome of the bout being pretty much what you’d expect. It’s only later that Ollie, in an effort to make Stan slip on a banana peel to collect the insurance on him, inadvertently sets a trap for pie delivery man Charlie Hall — and the outcome of that is also pretty much what you’d expect.

For years — decades — all that survived of The Battle of the Century was the pie fight, and only a few minutes of that, preserved by producer Robert Youngson in his compilation The Golden Age of Comedy (1957). As luck would have it, though, most of Reel 1 surfaced in the 1970s, while a complete Reel 2 finally turned up in 2016 (and kudos to historian/collector Jon Mirsalis for finding and sharing it). So what we have now, and what we saw in Columbus, is complete (minus a couple of minutes that seem lost for good) for the first time in 90 years.

Another comedy duo, Ole Olsen and Chic Johnson, were back again at Cinevent, after Helzapoppin’ (1941) in 2015 and Crazy House (’43) last year. This year it was Olsen and Johnson’s next picture, Ghost Catchers (’44). For once, an O&J picture had an actual plot — at least, about as much plot as their madcap antics would allow. Olsen and Johnson (using their own names) played nightclub owners who volunteer to help neighbors Walter Catlett and his daughters Gloria Jean and Martha O’Driscoll, who have just moved into the house next door — which turns out to be haunted by a ghost who does a soft-shoe shuffle to “Old Folks at Home”. With our heroes running a nightclub, and with Col. Breckinridge Marshall (Catlett) having moved to New York so his daughters can sing at Carnegie Hall, there were plenty of songs in the picture’s modest 68-minutes, inserted amid the comedy (very funny) and hauntings (surprisingly creepy).

This was followed by another Gloria Jean musical from Universal, Moonlight in Vermont (1943). Gloria Jean was essentially a second-string Deanna Durbin, but she had a charm of her own, and her presence graced this picture as it did Ghost Catchers. Here she played a country girl transplanted to a New York music school, who then enlists the help of her fellow students to return to Vermont and save the harvest on her uncle’s farm. In this one she was teamed with a blandly talented 17-year-old song-and-dancer named Ray Malone, best described as Donald O’Connor without the personality.

The third day of Cinevent wound up with The Amazing Colossal Man (1957) from 1950s schlockmeister Bert I. Gordon, in which army colonel Glenn Langan is exposed to radiation during a nuclear bomb test that causes him to grow to gigantic proportions and menace Las Vegas (far more subdued in ’57 than it is today) before being blasted off Hoover Dam into the depths of Lake Mead — I guess you could call it The Incredible Enlarging Man. At lunch that day, I rather flippantly dismissed producer/director Gordon as “Ed Wood without the alcoholism”, but that was really unjust — Gordon’s movies were never as bad as Wood’s. Still, they do tend to strain 1950s nostalgia to pretty near the breaking point.

To be concluded…